Paola F. Antonietti, born in 1980, is head of the MOX Modelling and Scientific Computing Laboratory of the Department of Mathematics and professor of Numerical Analysis at Politecnico di Milano.

In 2015 she obtained a SIR (Scientific Independence of young Researchers) grant, funded by the Ministry of Universities and Research, with the project ‘PolyPDEs: Non-conforming polyhedral finite element methods for the approximation of partial differential equations’. In 2020, she received the ‘Jacques-Louis Lions’ Prize, awarded every two years by the European Community on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences (ECCOMAS) to young researchers giving outstanding contributions to the field of computational mathematics.

In 2024, she will present the results of her research in an invited lecture at the ‘European Congress of Mathematics’, the second largest mathematics event worldwide, organised every four years by the European Mathematical Society.

Let’s start from you, what studies did you do and where did your passion for mathematics arise from?

People often imagine the mathematician as a somewhat isolated individual, but I would like to emphasise that I had a completely normal childhood!

From an early age, I showed a strong interest in science: I loved studying and was lucky enough to meet a maths and physics teacher in high school who advised me to enrol in the Mathematics programme at the University of Pavia, which is renowned for its excellence.

Those years of study were challenging yet wonderful. I graduated at 23 years old and at that moment I realised how much I loved studying. I then went on with a PhD programme at the University of Pavia, where I spent three extraordinary years devoting myself exclusively to research in the group led by Professor Franco Brezzi and Professor Donatella Marini, in a high-level international environment. During my PhD programme, I had two internationally renowned supervisors, Professors Annalisa Buffa and Ilaria Perugia, both of whom later moved to prestigious European Universities. I also spent a period at Oxford University under the guidance of Professor Endre Suli, an expert in numerical methods for differential equations. After my PhD, I continued my adventure in the world of research, spending a period as a research fellow at the University of Nottingham, and then I won a researcher competition at Politecnico di Milano and come back to Italy, in the group of Professor Alfio Quarteroni.

I came from a theoretical background and here, thanks to Professor Quarteroni and the MOX Lab ecosystem, I learnt that I really love applications, that I enjoy exchanging ideas with fellow engineers, designers and architects. At the beginning it was not easy, but I learnt a lot and grew professionally.

You have recently won an ERC SYNERGY GRANT, a very prestigious and large grant from the European Research Council, for the NEMESIS (New Generation Method for Numerical Simulator) project. What is it and why do the ERC reward synergy?

The European Research Council (ERC) is the leading pan-European funding body for supporting frontier research and promoting scientific excellence in all fields. The ERC SYNERGY GRANT funding line, one of five available, is based on the idea that the challenges and problems addressed are so complex and cutting-edge that they require the synergetic contribution of several researchers, so proposals must involve a team of 2-4 Principal Investigators.

The NEMESIS project team consists of four Principal Investigators. Besides myself,there are my colleagues Lourenco Beirao da Veiga (University of Milan Bicocca), Daniele A. Di Pietro (University of Montpellier) and Jerome Drouniou (CNRS). We are all applied mathematicians, experts in the construction of methods for computer simulations, focused on the study of emerging problems in engineering and applied sciences in general. Although we all have a background in numerical analysis, we still complement each other.

What are the main applications of your study?

The role of computer simulations is becoming increasingly crucial in dealing with problems that are priorities in the context of sustainable development. Mathematical models and the associated numerical methods used to solve them by computer have become increasingly complex, so much so that they have significant limitations in terms of computational costs and environmental impact, as supercomputing clusters require significant energy resources.

In the NEMESIS project, we aim to develop a new generation of new methods that are increasingly accurate and efficient, including by using Artificial Intelligence. We will also validate these methods in application contexts related to sustainable use of the subsoil and advanced production processes, such as that of aluminium, which is known for being highly energy intensive. Even small improvements in the production process, which can be computer-simulated before implementation, can lead to significant energy savings.

Would you therefore recommend an experience abroad?

Yes, I would. It was a very formative and growth experience for me. The research ecosystem in both Oxford and Nottingham was top-notch, but I wanted to come back to Italy. An international experience is a great added value for the curriculum of young researchers: you learn a lot, especially in building relationships and experiencing new possibilities.

The number of ERC grants allocated is limited (37), Italy ranks fourth with five projects and Milan is in the lead with four researchers. How did you win?

ERC calls are extremely competitive. In the 2023 call, only 37 project proposals (about 9%) out of the 395 submitted received funding. Outlining and writing the research project took us a year and a half of intensive work.

The evaluation of project proposals in the ERC Synergy line has three phases. In phase 1, a single committee (panel) consisting of around 80 members and 5 chairs (panel chairs) ensures an initial selection phase. Following phase 1, five multidisciplinary panels, including external reviewers with specialised expertise, are set up to review the projects. In the third and final stage, the researchers of the selected projects are invited to Brussels for an interview. The 5 panel chairs are known from the start of the evaluation process, while the full list of members of the 5 multidisciplinary panels is only made known once the evaluation process is concluded.

For the NEMESIS project, my three colleagues and me were interviewed together for 45 minutes: 10 were for our presentation and the rest of the time we were bombarded with questions. That interview was by far the most difficult thing I have ever done in my professional life. [she laughs]

We wanted to emphasise the fact that our project was highly integrated and collaborative while enhancing the differences between each of us the proposers. The other major difficulty is that the panel is multidisciplinary and you cannot not its composition a priori, and therefore, we had to be sufficiently ‘technical’ to have the panel members who were culturally closer to us appreciate the vertical content, while also present our project from a wider perspective to also address the panel members from other disciplines.

It was a major investment of energy, but it is worth the effort: preparing a project is an experience that makes researchers grow and forces them to streamline ideas and confront with peers. NEMESIS is the only mathematics project that has been funded in the n2023 call. This is the second ERC Synergy Grant in the history of Politecnico di Milano: I feel the responsibility but also the enthusiasm for this challenge.

After this experience, what advice would you give to young researchers?

You have to try! After working hard to build your international curriculum and a network of collaborations, it is crucial to take time to calmly reflect on what you want to do in a 5-6 year time horizon. This phase is extremely important because we are often overwhelmed by the daily work routine, including teaching and institutional commitments. Ask yourself where do you see yourself in 5-6 years: you need to study hard to understand how research is evolving and where you want to be.

What’s your advice to girls? How did you manage to make your way in a purely male world?

I would especially encourage girls to try this path. Gender bias is still present in academia and society as a whole, especially in the scientific field, although I think big steps forward have been made.

During the initial stages of my academic career, I did not experience this problem directly. I was fortunate to grow up in an environment of excellence where I never felt any signs of discrimination, or perhaps, if there was, I did not perceive it.

I began to experience the so-called vertical segregation as I progressed through the academic grades; even today, I often find myself being the only woman at the table. However, I firmly believe that success lies in diversity. Each one brings their individual experience, background and sensitivity, and this the way each one of us helps solving problems from different perspectives.

I believe it is crucial for future female researchers to show that ‘we can do it’. There is often this implicit belief that women researchers must be ‘a little better’ than their colleagues, even with equal skills. In my opinion, we should demolish this stereotype, especially in top positions, where there is still significant inequality. Politecnico shows great sensitivity in this regard. It shows a tangible will to take action.

Politecnico shows great sensitivity in this regard. It shows a tangible will to take action.

And you made it to the top, you have recently been appointed head of MOX, replacing legendary Professor Quarteroni

It is an immense honour and a huge responsibility at the same time. The MOX Laboratory is an internationally recognised excellence. Since Alfio Quarteroni founded it and over the many years he guided it, the MOX was able to anticipate many challenges and establish itself on the international research scene thanks to its international vision and outstanding scientific quality.

I am deeply honoured to have received this prestigious appointment from the Head of the Department of Mathematics, Professor Sabadini: I am devoting great enthusiasm and energy to the laboratory, and I hope I will be able to help consolidating the position of the MOX on the international research scene.

Are you currently dealing with any particular research work?

We are working on a wide range of mathematical problems and their application contexts. Mathematical and numerical modelling, applied statistics and scientific computing are a universal language. We are addressing issues ranging from life sciences to computational geophysics, from advanced manufacturing processes to issues of social inclusion, and this using the same formal tools as mathematics and being able to dialogue across languages and interfaces.

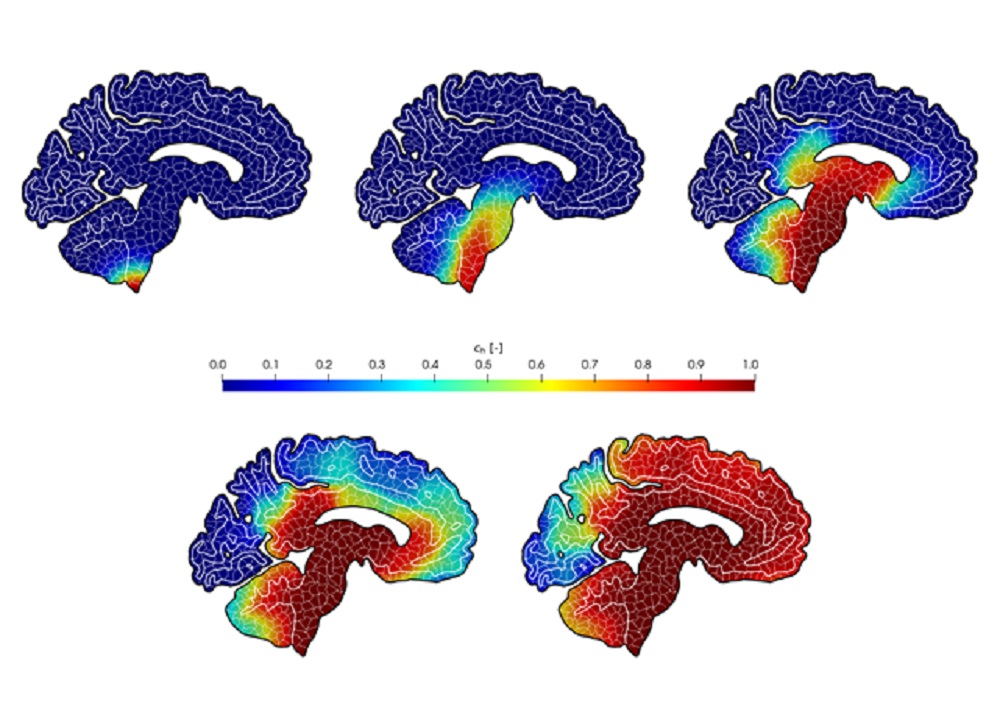

Something I have always been fascinated by is the fact that essentially, mathematical formalism is universal. We can quantitatively describe the effects of an earthquake on the built environment as well as the neurodegenerative mechanisms occurring in the human brain due to diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s using equations that are very similar to each other.

MOX researchers operate in a unique and challenging environment, thanks to their ability to dialogue with a variety of actors, ranging from engineers to medical doctors, from biologists to designers.

And so this myth of the mad scientist studying in isolation must be dispelled…

Major global challenges such as, for example, sustainability or an ageing population are positioned at the borderline between disciplines. The concept of the ‘all-rounder’ is now obsolete because our knowledge has deepened so much that progress is only possible through integrated research teams, not only in terms of expertise but also in terms of gender identity and the socio-cultural context in which this knowledge has developed. Only in this way can we stimulate the innovation needed to tackle such complex challenges.

What fascinates you about mathematics?

I have always appreciated the approach of tackling a concrete problem emerging from discussions even with very different interlocutors and identifying the key elements related to the question posed. Next, I like to abstract the problem and describe it using a universal language such as mathematics, and then observe the concrete results through computer simulations. This ability to analyse a problem by decomposing it into simpler problems and then putting the pieces together has always held a strong fascination for me.

Going back to the girls, how can we get them to take this path?

It is a very difficult topic, there are so many levels of analysis and action, I speak both as a mother and as a scientist. We know that gender stereotypes are formed at a very young age and very often in the social and family context, and they impose us certain patterns of behaviour and life choices. It is an effort that mist involve the whole of society. As I tell my daughters, if you put your mind to it, you can do anything you want. Work must be done in all age groups to educate for equality.

Regarding future female students, they should break up their adherence to stereotypes that associate the STEM areas (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) with the male gender, in order to give everyone the same opportunity and pass on virtuous models. The University has invested significantly in this.

And then there is the phase of female researchers in the early stages of their careers. This delicate period usually coincides with that in which they start a family and become mothers. I believe the University has made great efforts on this front, too. Concrete actions such as crèches, summer centres, welfare, help one not to have to choose. Services and instrument can make a difference.

Today, there is a tangible change of course and there are positive signs: the first female rector at Politecnico, the first woman at the head of the Conference of Italian University Rectors (CRUI), all three public Universities in Milan led by women: all this means that we can do it.