Smart working, personalised schedules, increasing autonomy: flexibility at work appears to be the perfect recipe for well-being. But is this actually true?

A study conducted by the Politecnico di Milano together with the University’s Graduate School of Management has been published in the Journal of Vocational Behaviour. It shows that being able to choose where and when to work is in itself not sufficient; what makes the r A study conducted by the Politecnico di Milano together with the University’s Graduate School of Management has been published in the Journal of Vocational Behaviour. It shows that being able to choose where and when to work is in itself not sufficient; what makes the real difference is the control that people feel they have, not only at work, but also over their social boundaries. eal difference is the control that people feel they have, not only at work, but also over their social boundaries.

The study looked at more than 1,400 employees of an Italian bank, and identified four flexibility profiles across two dimensions: control over work and control over personal life. Only those with both forms of control really experience well-being, motivation and work-life balance.

We talked about this with Gabriele Boccoli, a researcher at the Politecnico and co-author of the study, to discover how the experience of flexible working really changes.

How did you come to be working in this area?

My interest in research began during my master’s degree. After I’d finished my studies I worked for a couple of years, but I felt the need to delve deeper. So I applied to do a doctorate, and I got a place in the Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering, where they were looking for applicants to research topics close to my background in sociology: engagement, work psychology, HR Analytics.

My interest in these subjects has grown over time, and research into organisational behaviour and the well-being of people at work has now become my primary focus.

How did this research come about?

The study is part of a larger project by the Joint Research Platform: People Analytics for Empoloyee Engagement & Wellbeing, which I am a part of. We work together with companies to study the impact of HR practices on the well-being of employees and their performance. During the pandemic, we saw the emergence of a clear, but not always consistent, relationship between flexible working and well-being.

In theory, flexibility should improve your quality of life and your performance. But some studies have also shown the opposite effects: isolation, stress, even burnout. This is known as the autonomy-control paradox. We asked ourselves: when does flexibility really work? And when might it have a boomerang effect?

Why did you choose to study a bank?

We’d already contacted that business and a promising situation had arisen: they had implemented various flexible working practices — both in terms of space and time — and this allowed us to work on a diverse sample of people, who had experienced different degrees and methods of flexible working.

The study can also be replicated in other contexts, as long as there is a minimal flexible system to work on. There are certainly some roles for which it is not possible, but in general the results are useful for many types of organisation.

How did you design the study and what did you discover?

We used a longitudinal method, examining the data at two different points in time to detect any changes in the flexibility profiles. The sample consisted of over 1400 employees of an Italian bank.

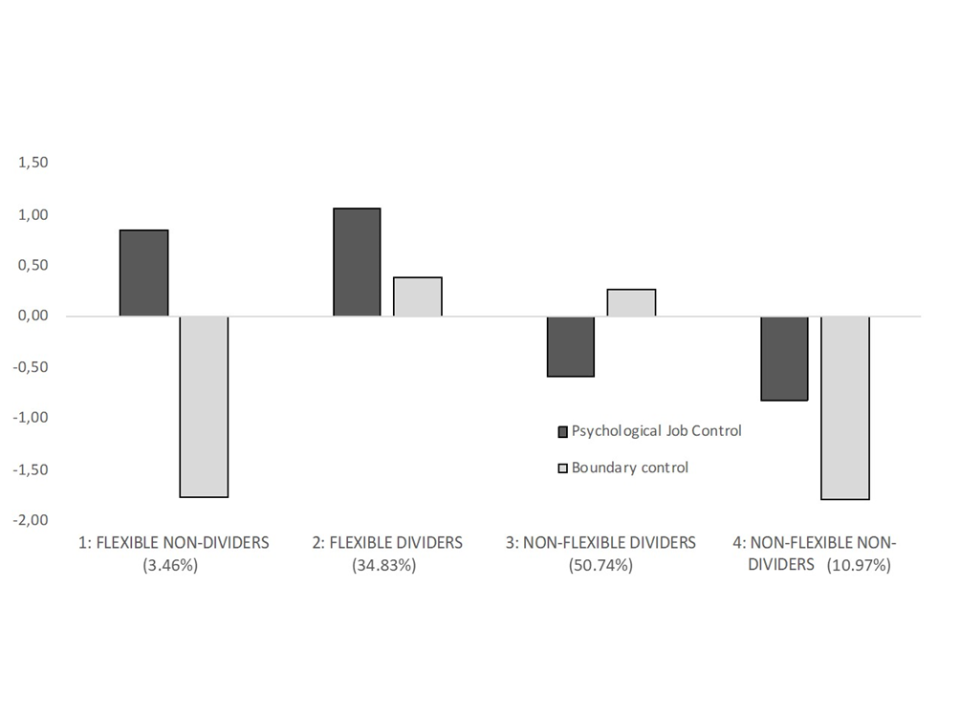

We constructed four profiles, combining two basic psychological dimensions:

Psychological job control, i.e. the perception of control over where and when one works.

Boundary control, or the ability to manage and protect one’s social roles (e.g. those of being a parent, partner, child, etc.).

A very interesting picture emerged from this. Some individuals have a high level of control on both fronts, others on only one front, and some on neither front. The four profiles are:

Flexible dividers – high control both at work and over social boundaries. They are the best off and have the highest levels of well-being in terms of job satisfaction, work engagement and work-life balance, which remain stable over time.

Non-flexible dividers – low control at work, but high over social boundaries.

Flexible non-dividers – high control at work, but low management of social roles.

Non-flexible non-dividers – low control on both fronts, and in a generally bad position.

Which profile struck you most strongly?

The most interesting was that of the flexible non-dividers. This profile turned out to be the most variable over time: many people went from there to other “healthier” profiles, achieving greater boundary control.

In general, those subjects with poor control over social boundaries are also the most vulnerable: they report lower levels of well-being, engagement, satisfaction and work-life balance. This supports the idea that true flexibility is not just a matter of time or place, but also — and maybe especially— an ability to manage personal and social roles.

Did gender play a role in this process?

Yes, gender was one of the important predictive factors. The data showed that:

Men tend to conform more frequently to “positive” profiles, with high control both at work and over boundaries.

On the other hand, women were more often classed as “non-dividers” i.e. people who lacked effective management over their social roles.

This difference may reflect cultural and social dynamics. In many contexts, women continue to bear a heavier burden with regard to family management, which translates into greater difficulty in separating and balancing the different areas of life.

Did you have any problems in carrying out the study?

Actually no, because our collaboration with the company went very smoothly. The HR department was very helpful and closely involved: we created the study together, including the design of the questionnaire. Of course we oversaw the scientific aspect, but they helped us make the questions readily understandable for the employees, without any loss of rigour. It was a collaborative and constructive process.

What advice would you have for a student wanting to pursue an academic career?

First of all: apply for a PhD. That’s step one. It’s a long process: doctorate, post-doc, researcher, associate professor, and so on. You need perseverance, curiosity, good average results… and above all a real love of studying.

For me the best aspect is being exposed to constant intellectual stimulation. Every research project gives one an opportunity to learn, to ask new questions, to explore topics that are very different but also interconnected. It’s a varied, creative job that keeps you mentally alert.

What do you like best about your work?

Definitely the curiosity. We often associate this with children — a desire to understand, to find out more, to ask questions. Doing research also means acknowledging the fact that there is still so much we don’t know. The more you study, the more you come to realise that there are multiple perspectives, multiple truths. And I believe this also helps you become more tolerant and open.

One last question: could you recommend a book, a film or a documentary that deals with the themes in your research?

I can think of lots of academic texts — but they’re not the best way to start! However, to give you a example, I really enjoyed a documentary about the world of work in Japan. It shows how cultural and social factors can lead to aberrations such as workaholism or burnout. Stories like that help one understand how well-being at work is a cultural issue as well as an organisational one.

I think I’d also recommend the film The Devil Wears Prada. It’s certainly well-known, but it does give a very good picture of some of the tensions involved in maintaining a balance between work and personal life, the sacrifices required in certain professional contexts, and the roles — often imposed — that people find themselves playing. Again, the issue of gender is central to the plot.

Among the books, I would recommend One, No One and One Hundred Thousand by Pirandello, because it deals with the theme of identity and the roles that each of us plays in everyday life with great force — often in an unconscious or fragmented way. Alternatively, Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life can also offer interesting ideas, especially for those with a more sociological interest. It is a text that helps us reflect on how we present ourselves to others and how we manage interactions, even in the workplace.