In a fast-moving world, cycling is not just an environmentally friendly mean of transport; it is also one that lets you discover hidden treasures on uncharted routes without haste, taking in the scenery at a leisurely pace. But experts are needed to map those routes, along roads and corners of Italy that are normally off the tourist trail, and to set the pace for a “slow” and ethical tourism: these experts can be found at “E-scapes”, the Observatory for the study and promotion of the areas crossed by the slow routes, supported by the Department of Architecture and Urban Studies – DAStU at the Politecnico di Milano. The aim? To support and promote a “Network of Historic Roads and Villages” that contributes to the development of “middle territories”, towns and villages along roads connecting large cities, exploiting existing infrastructure for a kind of tourism that encourages sustainable mobility by combining cycling, walking and travelling by train.

One of the research focuses of “E-scapes” is Italy’s UNESCO sites, including the 60 World Heritage Sites, 21 Biosphere Reserves and 12 Geoparks, as well as assets classified as Intangible Heritage (cultural traditions such as the art of dry stone construction and the Mediterranean diet) and others such as Creative Cities. Most of the routes analysed and tested so far aim to interconnect these, along with other assets with a more local value but equally worthy of mention. Andrea Rolando, a professor at DAStU, one of the Observatory’s founders in 2018 and its current coordinator, talked to us about the project.

Where did the inspiration for the “E-scapes” Observatory come from?

The idea was to see how the areas crossed by the slow routes could be promoted by combining traditional and fast infrastructure, such as railways and motorways, with routes that can be travelled on foot or by bicycle. In recent years, high speed trains have steadily brought the big cities closer together – first Turin and Milan, and then Bologna, Florence, Rome… At the same time, this phenomenon has in a way alienated and erased the middle areas. So, we initially began with the Milan-Turin routes, trying to understand how the different speeds could coexist. And we started by studying the relationship with the motorways, with the local railways, with high speed trains, and by integrating not only the actual network of communication, but also the digital one: thence the name “E-scapes”.

Was the Milan-Turin route your first project?

Yes, on the occasion of Expo 2015. The theme of Expo was “Feeding the planet”, and we thought that the ideal places to fully understand the relationship between food and people were what we called the “natural pavilions” of Expo, such as the rice paddies that abound between Turin and Milan. In collaboration with the Italian Pavilion, we tried to travel by all the waterways between Turin and Milan, like the Cavour Canal that takes water from the Po and was created to irrigate those very rice paddies: it seemed the perfect place to show the relationship between food, landscape, water and slow mobility. We demonstrated on the spot that it is possible to travel along the canal towpaths, thus connecting the two cities: pedalling along the Cavour Canal, you pass close to the motorway almost without realising that it is there. So we started to develop the idea that infrastructures with different speeds can be compatible with each other. At the same time, we focused on all the possible transport hubs that, thanks to the increasing availability of digital communication networks, are developing more and more into new workstations. For example, crossing the plain, the Cavour Canal skirts the Turin-Milan motorway for a short section, at a service area. And we wondered: why can’t these service areas become places that serve not only the motorway, but also people who travel by bike? Moreover, these lands are also crossed by several of the Vie Francigena trails, including the one that descends from Gran San Bernardo to Vercelli, and then continues towards Pavia and Piacenza; and the one that descends from Valle di Susa through the pass of Moncenisio and Monginevro and then continues to Vercelli; and then there are other slow routes linked closely to the waterways, such as the Ivrea Naviglio.

Was this what led to the first project associated with UNESCO sites, the UNESCO Grand Tour of Piedmont?

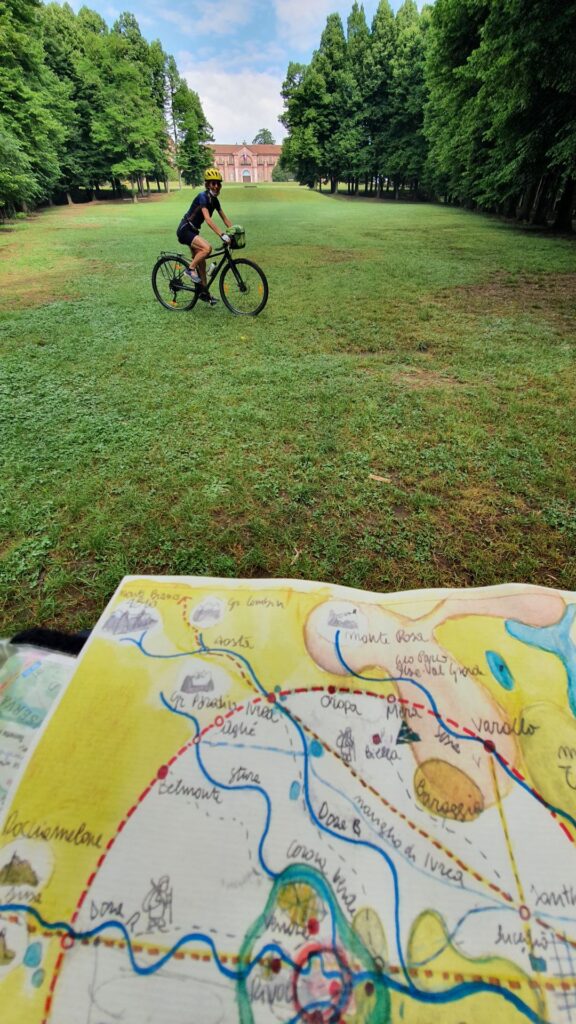

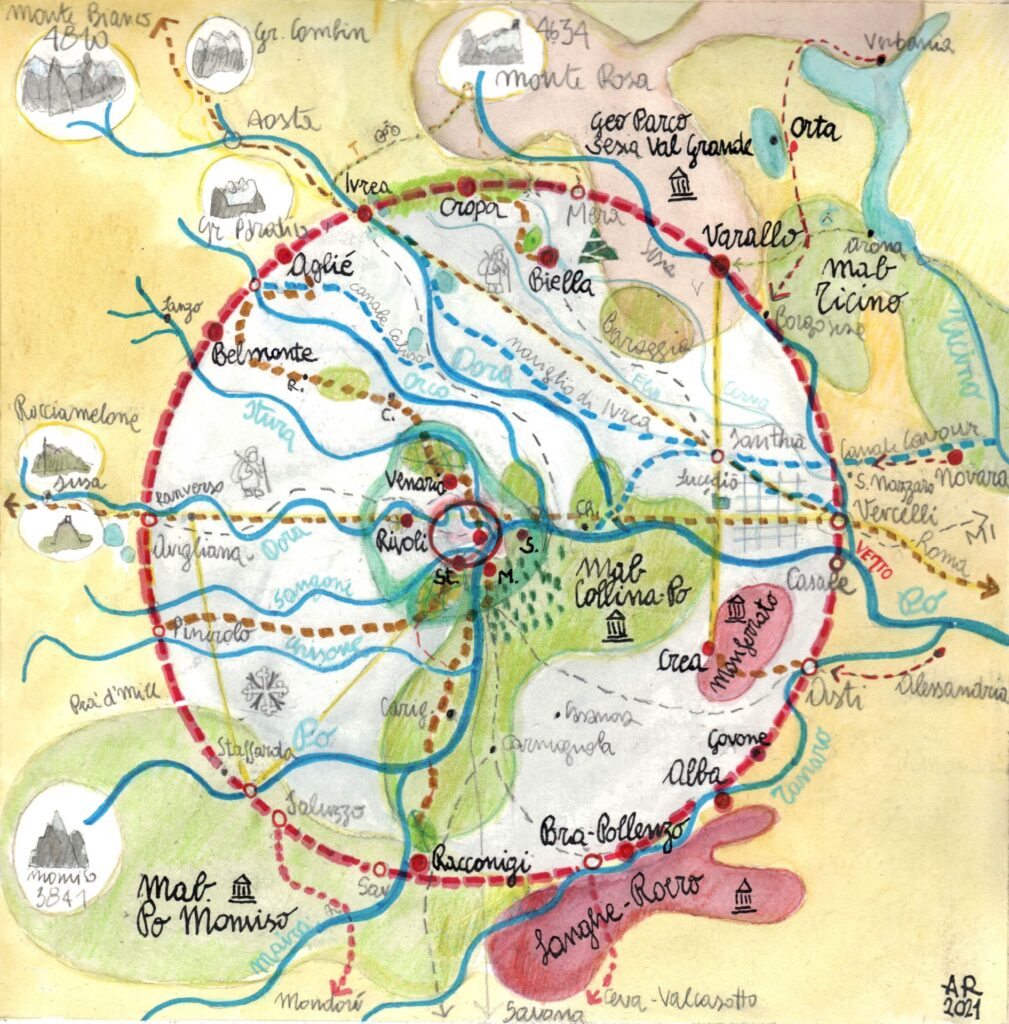

This is the most multi-faceted project, started in 2020 and based on an agreement between Politecnico di Milano and the Piedmont Region. It is a 650 km route that touches all the Piedmont UNESCO sites: not just cultural heritage sites (the Sacri Monti, the Royal Residences of Turin, Alpine pile-dwelling sites, Langhe and Monferrato, Ivrea) but also the biosphere reserves for man and nature of Monviso, the Po hills, Ticino Gran Valle Verbano, and the intangible heritage with the “Creative Cities” of Biella, Alba and Turin. It can be reached by bike and train: you can take the train, get off at Vercelli, ride to Asti and then return either to Turin or Milan. The entire 650 km loop can also be covered in stages of 1-2 days, or as a 7-10 day holiday: 60 km a day is feasible even for people who are out of training, and the roads, the so-called “dirt roads”, already exist so no new infrastructure is needed. You can find all the itineraries and descriptions on the website Visit Piemonte of the Piedmont Region: this is an excellent example of applied research, of grounding of the results and of bringing them to a common level of use. This project also received the “Accessible Cities” 2024 award from the National Institute of Urban Planning and the route has been published in the “By bike” series of National Geographic and on the magazine “Destinations, Italy Unknown” which is widespread abroad.

Is there a similar project for Milan and its hinterland?

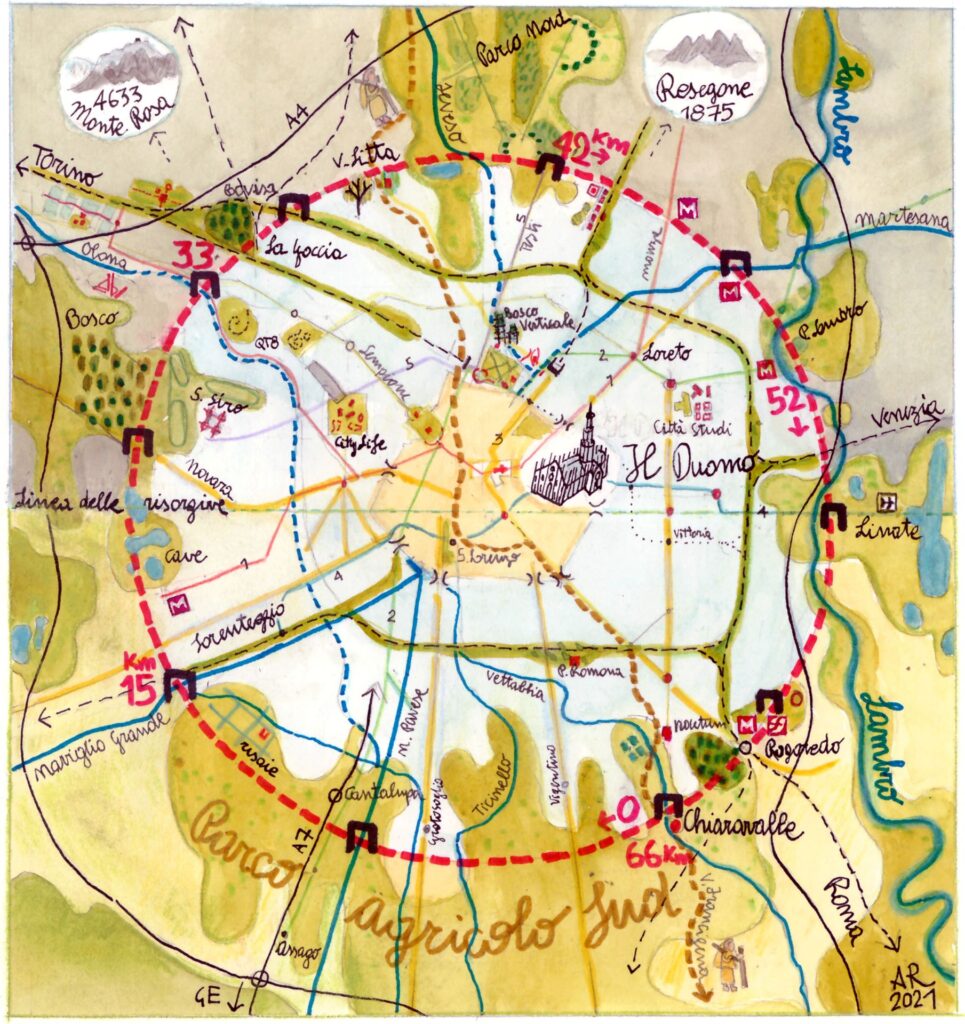

Last year, we were commissioned by the Culture Directorate of the Lombardy Region to apply the same model tested in Piedmont. The loop that connects the UNESCO sites in Lombardy is a long one – 1,200 km – and it is a little known fact that Lombardy is the region with the highest number of UNESCO sites in Italy. From Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper to Crespi d’Adda, the Sacro Monte of Varese, Mantua and Sabbioneta…. Not to mention the Creative Cities, the intangible heritage and the extraordinary biosphere reserves for man and nature. Lombardy is also the only region with a UNESCO site that is also a FAI asset, the Monastery of Torba near Varese. So, in this case, we expanded the scope of interest a little, even if the focus of the assignment is heritage sites. Our approach is to map everything that could attract tourists: including FAI assets, but also contemporary architecture. For example, the Pritzker Architecture Prize is like the Nobel Prize but very few people know that in Milan there are at least a dozen buildings designed by architects who were awarded this prize for their work: the Feltrinelli Foundation by Herzog & de Meuron, the Mondadori building by Oscar Niemeyer, the Prada Foundation by Rem Koolhaas, the Apple store by Norman Foster, the buildings by Renzo Piano and Zaha Hadid, City Life… In short, there are places that we believe should be included into a touristic package because here there is not only the historical heritage, but also an interpretation of the territory linked to contemporary times that we, at Politecnico di Milano, believe is very important.

What methodological approach do you follow in these projects, how do you carry out your research? Do you start by mapping a territory and then try to create a route between the places of interest?

That is exactly what we do. For example, for the UNESCO Grand Tour of Lombardy, we have currently completed around 950 km of network and we have gone out to personally perform inspections, because it is by going out and about that we come across elements that are perhaps not considered at a general level, but they become relevant when they’re observed along routes that delve into the most hidden corners of the landscape, out of the ordinary ones – small details, but important for tourist purposes. A lock on a canal, a view of Monte Rosa from the Naviglio Grande cycle path, or a monumental tree… If there are elements able to surprise tourists along the way, we map them and add them.

So starting from theory, you then check them out one by one on the ground. It must be a really extensive job!

Yes, it’s actually an extremely detailed work. It took us about twenty days to inspect these 950 km. And then there are the “mistakes” too, often turning into pleasant surprises… We plot all the routes using GPS, we mark them on the map to see exactly where we have been, check if there are any mistakes and decide what is worth visiting. For example, there could be a detour from the original track because we notice some direction to a monastery and, after visiting it, finding ourselves adding it to our map, instead of riding straight past it on our prearranged itinerary. We should complete the inspections soon. By the end of the year, we will deliver the material to the Lombardy Region and then we would like to take the next step, like in the Piedmont project; that is, make all this information available so that it can be used for tourism purposes.

You have also worked in the rest of Italy, with other partnerships.

Yes, under another agreement with the Alta Murgia Park we have connected five UNESCO heritage sites in Puglia and Basilicata: the Umbra Forest, Monte Sant’Angelo, Castel del Monte, Alberobello and Matera. We joined other experts and travelled this route, which skirts an important infrastructure: the Apulian Aqueduct. Here too we applied the concept of intermodality, with slow infrastructure that can be reached by train and then by bike. We travelled on the night train to Foggia, then by bike to the Foresta Umbra and from there to Monte Sant’Angelo and Canne della Battaglia, where there is a small train station; here we took the train to Spinazzola about thirty kilometres away. We then rode back to Castel del Monte, crossed the Alta Murgia Park, and took the train again to Gravina di Puglia. All this to promote slower and more sustainable tourism, because getting to Castel del Monte by car, for example, is an ordeal what with the chock-a-block car parks and traffic jams… Incidentally, they are transforming the aqueduct into a cycle path that passes just below Castel del Monte.

Then, we carried out a similar project for the UNESCO sites in Sicily, commissioned by a consortium of municipalities, SoSviMa – Madonie Local Development Agency. We arrived at Falcone and Borsellino airport by plane and took the train to Palermo, which is a Unesco site. From there, we rode 10 km to Monreale and it was a real urban exploration adventure, because it is certainly not an easy road; we took the train back to Cefalu for the Duomo, and ventured into the inner Madonie, a UNESCO geopark. This route has also been published on the magazine “Destinations, Italy Unknown”.

So the final goal is to promote not only the big cities but also the often lesser known surrounding areas. In short, trying to shift tourism onto different routes and not just the well-trodden Venice, Florence, Rome…

Absolutely. The real aim is to rebalance the territory, and to give an alternative to the most visited places which often suffer from over-tourism. We want tourists to move around and see the wonders all around them. That’s why we started with UNESCO sites, thinking of them as points of departure and of destination, but aiming at putting the middle areas into the spotlight. For us, from a town planning and design point of view, this is of paramount importance: the area crossed is important, not the destination or starting point without taking in everything you can find along the way. If we can appreciate what is in between, we are doing a great service to the territories and taking pressure off the overcrowded ones. It is like a system of communicating vases: we need to have many vases, so the level of liquid is the same for everyone. The high-speed network has greatly favoured the big cities. We would like to balance that out by promoting the use of local trains that make those “middle areas” accessible, and tourism could act as a catalyst.

Let me give you an example: on the Oropa Way there is the Oropa Sanctuary with the Sacro Monte which is a UNESCO heritage site. The Santhià railway station, on the Turin-Milan line, has become the starting point for the very easy trek, which takes you to the Sanctuary in three days. Many are attempting this trail and it has been successful precisely because it has somehow promoted the territory, even its most hidden corners. We must ensure that the local railways, which are widespread along all the Italian territory, are enhanced and that the secondary lines to keep on operating.

Do you think the railway system is ready for this? Local transport, as commuters know, is often extremely stressful…

Yes, sometimes they are inefficient, we have had hands-on experience of this because we always leave from Milan and it is often a question of balancing acts: you have to know the timetables, if the train accepts bicycles, run through the station… There is still much to be done, but a lot has already changed: in the early days we didn’t see anyone with bicycles on the train, now almost all regional, interregional and even Intercity trains have special carriages for bicycles but the high speed ones still don’t – unlike other European countries.

Are you passing on the experience gained in these projects to your students?

Of course, this year I taught the first course in English on mapping for tourism called “Mapping Strategies and Design Solutions for Tourism”. It is an elective and groundbreaking course for both urban planning and architecture and landscape. It was held in the second semester with 48 students enrolled, almost all from abroad.

Projects in the pipeline?

We would like to try to replicate the model in other regions, develop it in a more standardised way, since it could be to the advantage of both tourists and locals, and being that the characteristics throughout Italy are the same: motorways, motorway services, railway stations as a transfer point, slow routes to travel by bike and on foot…. Specifically, we are currently working on a crossing from Ravenna to Cerveteri, both UNESCO sites – so, from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian Sea, passing by other UNESCO sites such as Medici Villas, Florence and Val d’Orcia. We’ve mapped it, and we’re reaching out to partners to develop it with.

All photos featured in the article are provided by professor Andrea Rolando