The inauguration

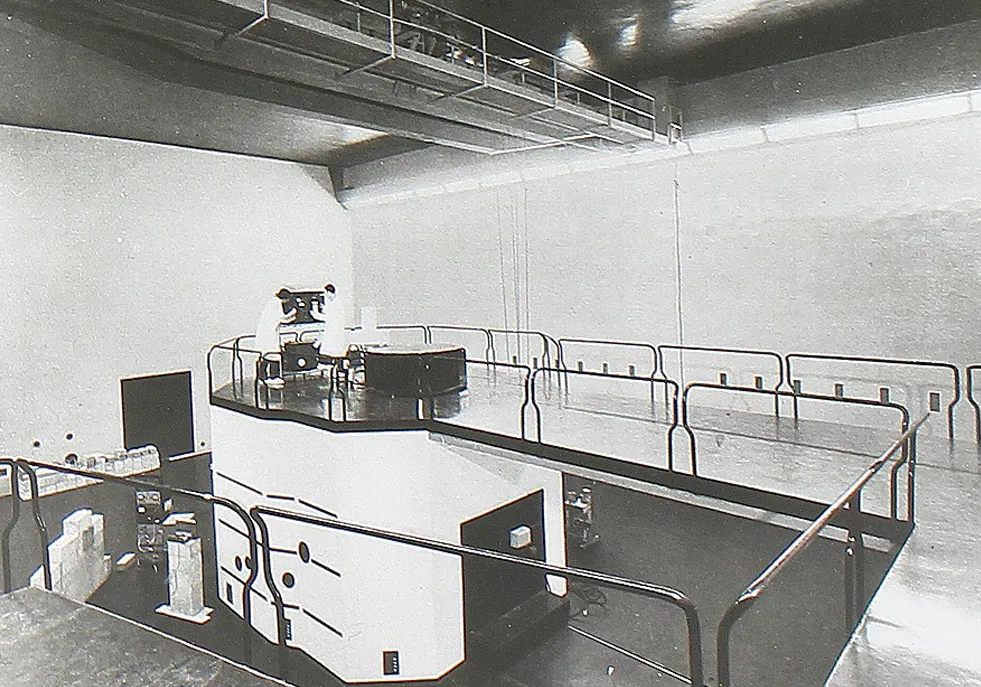

In 1959, some unusual activity was going on in the courtyard in via Ponzio, at the Politecnico di Milano. Technicians, professors and students had gathered around a concrete structure with curiosity and pride. It was the inauguration of the Enrico Fermi Centre for Nuclear Studies, better known as CESNEF. The concrete structure was the first research reactor built in an Italian university, a symbol of an era that looks to atomic energy as the key to the future.

The Politecnico had created a particular reactor. A small one for research purposes, designed not to produce energy but to train engineers, physicists and technicians capable of working with atoms. It was a “machine of knowledge” rather than of power, designed in years when trust in science was synonymous with progress.

Today, more than sixty years later, the plant is no longer operational. But its legacy lives on in the laboratories of the Department of Energy.

A story of continuity

To tell the story of CESNEF, we had a chat with two key figures in the field of nuclear power at the Politecnico di Milano, precisely,

Fabrizio Campi, Associate Professor of Nuclear Installations, expert in radiation protection and decommissioning, and Andrea Pola, Professor of Nuclear Measurements and Instrumentation, who has been working for years on radiation detectors and medical applications of nuclear power.

Campi came to CESNEF as a student in the late 1980s, when the reactor was already shut down. «I like to say that I took care of its corpse,» he smiles. «The plant was older than me, but when I arrived it was still full of scientific life. I assisted Professor Sergio Terrani, who was its director, until the official transfer of technical responsibility».

L54M, the reactor of the Politecnico, was a “homogeneous” experimental plant, a liquid solution of uranyl sulphate (UO2SO4) containing the fuel. It allowed for intrinsic stability.

«In case of any anomaly,» says Campi, «the temperature increase would have dilated the solution, automatically reducing the fission reaction. Basically, the reactor would have shut itself down. It was such a safe system that it never recorded either an accident or emergency in 20 years of operation».

In addition to the control rods and barytic concrete shields, which were more than 1.5 m thick, the reactor room was sealed by watertight doors and equipped with filters that could retain every radioactive particle.

«The chimney, which can still be seen in via Ponzio,» says Campi, «has never released a single radioactive atom. It was just an emergency system that was never used. It is weird to think that many considered the tower a symbol of something dangerous, when it actually represented the opposite, a perfect example of safe operations».

Science at work: research, measurements and radiochemistry

But what was being studied inside that reactor?

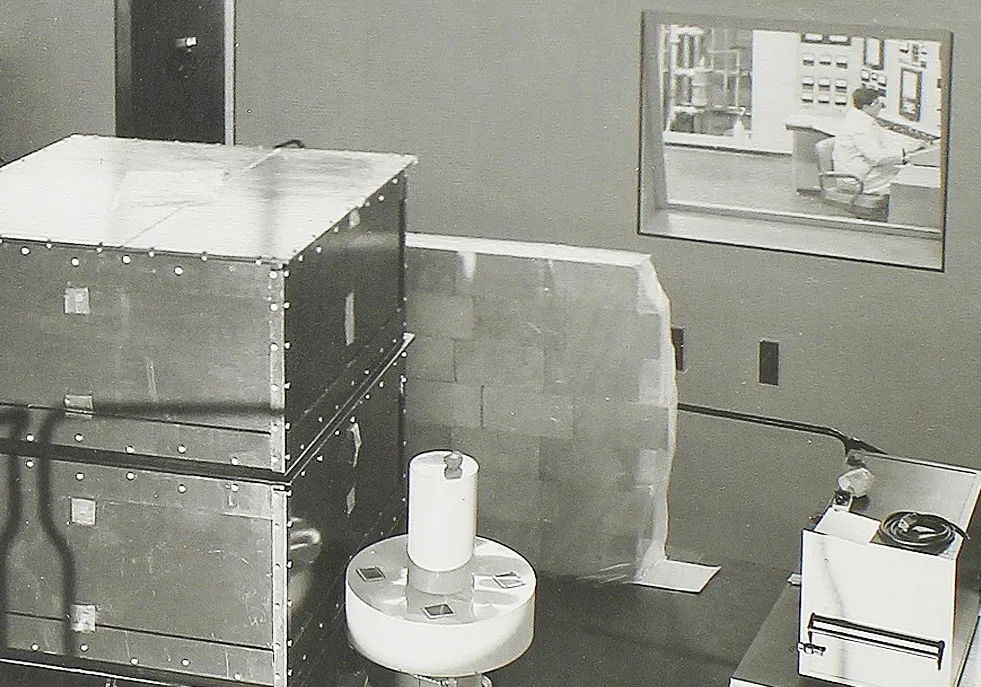

Campi tells us of a season of intensive scientific activity. «CESNEF hosted teams working in different but interconnected fields, such as reactor physics, systems control, radiochemistry, dosimetry, and instrumentation. Samples of materials were irradiated, nuclear reactions were studied, sensors and measurement techniques were developed».

The plant was connected to the radiochemistry laboratories through a pneumatic mail system, which allowed to safely transfer irradiated samples for analysis in the “hot cells”.

«This synergy has produced remarkable results,» says Pola, «such as the creation of a national reference dosimetry centre, which is also used by ENEL and other entities. That is where our calibration centre for radiometric instruments, included in the European metrology network for ionising radiation, was conceived».

CESNEF was also a national point of reference during the Chernobyl period in 1986.

«Our archives still preserve the traces of environmental monitoring carried out in those days,» recalls Pola. «The centre became a control site for the population, thus contributing to the national surveillance network. It is a testimony of how university research can also be at the service of collective safety.»

From the reactor to Bovisa: a new generation of laboratories.

When the reactor was being decommissioned, the Politecnico chose the path of relaunch with the decision to rebuild a new season of experimentation. Hence, nuclear activities were moved to the Bovisa campus.

«We have built modern irradiation rooms where we can work with controlled sources, and study the phenomena of interaction between radiation and materials,» says Pola. «’It is not a reactor, but a safe and advanced laboratory, which allows us to do training and research in the same spirit as then.»

Today the nuclear team of the Department of Energy is structured into several laboratories:

Radiation protection, directed by Professor Campi, where radiation protection methods and plant decommissioning are studied;

Radiochemistry and Radiation Chemistry, which investigates the transformation processes of radioactive matter;

Nuclear Measurements and Instrumentation, coordinated by Professor Pola, focused on developing detectors and spectrometry techniques;

and laboratories dedicated to new generation plants, reliability and risk, contaminant transport and ionising radiation metrology, which make the Politecnico a landmark at European level.

«The skills created at CESNEF have had a huge impact,» says Pola. «Today they are also applied in non-energy fields, such as nuclear medicine, hadron therapy, industrial diagnostics, and environmental protection. It is the demonstration that nuclear power is a cross-cutting science, which is not confined to a single sector.»

“Grateful – and somewhat sorry”

What would you say today to the pioneers who established CESNEF in the 1950s?

«I would say thank you,» replies Professor Campi. «Because without that seed, today we would not have such a renowned Master of Science programme in Nuclear Engineering. In the most difficult times, when students were few, that powerful story motivated us to continue. We are the only ones in Italy who still bear that name, and we are proud of it».

Pola goes on to say, «Perhaps I would also say that I am somewhat ‘sorry’. The closure of the reactor marked a loss of potential, though it was inevitable for historical and political reasons. However, I would especially say thank you for their vision. CESNEF was an act of courage and trust in science. Today that trust translates into hundreds of students, European projects, and growing laboratories. It is proof that far-sighted ideas do not die out. They are transformed».

A legacy for research

Today, the facility in via Ponzio is no longer an active plant, but a symbol of knowledge.

Its legacy continues to train researchers and inspire an idea of science as a service to society.

From the L54M reactor to the Bovisa laboratories, from plant engineering to metrology, the common thread remains the same: safety, precision, and curiosity.

.