Music, science and healthcare: an unexpected trio. But perhaps not, according to Mirco Pezzoli, Researcher from the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering at the Politecnico di Milano. In fact, the three fields are united by sound. After years of research dedicated to spatial audio and musical acoustics, analyzing the sound of historic Cremonese violins, he now applies the same sensitivity and techniques to the medical field.

In an interview, we asked him to tell us how his research, through the AVATAR-SC project, is contributing to the development of an AI-based remote monitoring (telemonitoring) system that analyzes heart failure patients’ voices to detect early signs of clinical deterioration.

Combining engineering, medicine and psychology, the project aims to turn the most human tool we have – our voices – into a new digital biomarker, to improve patient care.

Let’s start with your career to this point: what led you to look at AI applications in healthcare and, in particular, speech analysis?

«I’ve always been fascinated by sound and music: that’s where it all started. That led me to choose the Sound and Music Engineering module as part of my Computer Science and Engineering undergraduate studies at the Politecnico di Milano. At that time it was based in Como. It’s now the Music and Acoustic Engineering course, run by Professor Augusto Sarti. During my thesis, supervised by Professor Sarti and Professor Fabio Antonacci, I discovered how much researching the science of sound processing fascinated me: not only the music itself, but the possibility of translating the characteristics of acoustic signals into useful data.

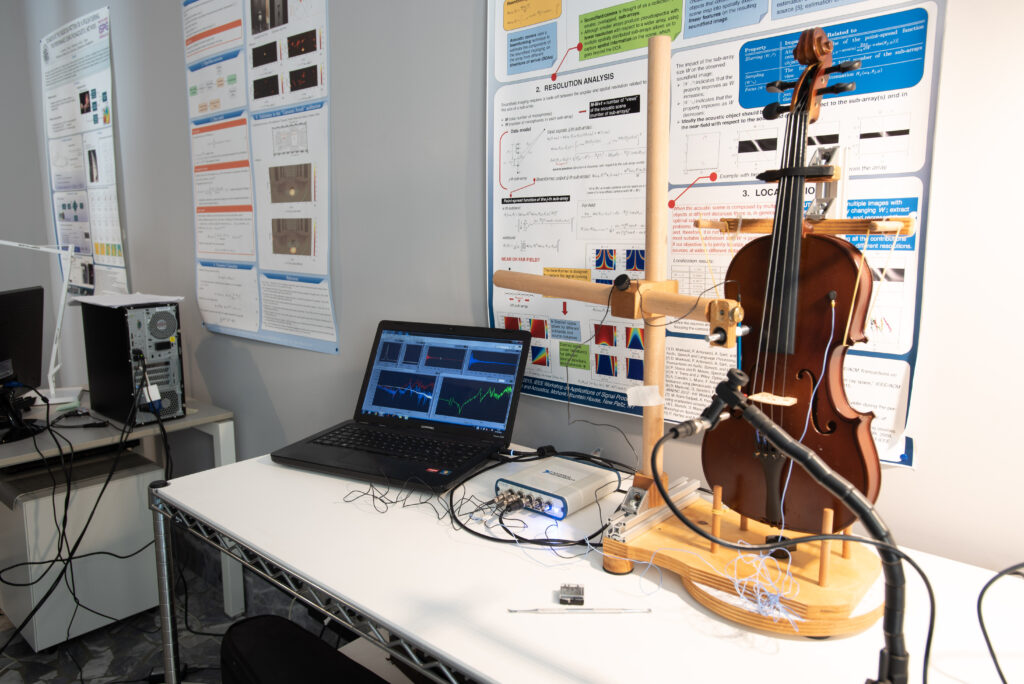

My career path continued with a PhD. I joined the Image and Sound Processing Group, which belonged to the Telecommunications area of the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering (DEIB). In recent years, I have had the opportunity to work on national and European projects and to collaborate with industry, allowing me to apply my machine learning and signal processing skills to industrial and creative contexts. Another foundational experience was my work with the Cremona Violin Museum, home to our Musical Acoustics workshop: there I was able to analyze the historic instruments of Antonio Stradivari, Guarneri del Gesù and other great violin makers, studying their “voice” and trying to understand the acoustic secrets that make them unique.

In a sense, this path led me naturally to AVATAR-SC: in Cremona I was analyzing the “voices” of the instruments; today, I’m analyzing people’s voices instead. It is a change of scenery but it holds the same fascination for me: I’m unveiling a set of nuances in a voice that can tell us so much more than it might seem at first. It’s therefore no longer just about art or the beauty of sound, but about the possibility that, by anticipating signs of fragility, we can offer patients tangible support to improve their quality of life.

When Dr. Alessandro Verde of the Niguarda Hospital proposed we participate in the project, I immediately took up the challenge. And so, we brought our skills into a new field that forms the crossroads between science, technology and healthcare».

How would you describe the AVATAR-SC project to a heart failure patient and what are the specifics of the Politecnico di Milano’s role in it?

«The AVATAR-SC project was created to simplify the lives of patients living with heart failure. The idea is to have an “avatar”, a virtual doctor with whom patients can communicate from home in a natural way, just as they would with a doctor in a clinic. This tool never replaces the doctor but supports them: it collects valuable information through these conversations, which is then made available to the specialist, who can assess the data and intervene promptly if necessary. For patients, it means avoiding frequent hospital visits and benefiting from continuous, discreet monitoring that feels as simple as a conversation.

Our role at the Politecnico di Milano is to give this avatar scientific ‘ears’. The team led by Professor Davide Tosi at the University of Insubria is developing the chatbot that will guide the avatar, while we focus on voice analysis: we are designing algorithms capable of extracting acoustic and linguistic descriptors that may reveal whether a patient’s health condition is changing. Some of these parameters are linked to voice timbre and frequency, others to speech rate or pronunciation; still others are more ‘hidden’ and detected through pre-trained neural networks. The goal is to find strong correlations between these vocal signals and clinical data, turning the voice into a true digital biomarker.

In other words, we are giving the avatar the ability to listen – translating the nuances of the human voice into useful information for doctors. This is where our unique expertise in sound processing and machine learning comes into play: enabling the voice to become an ally of health».

Voice analysis for clinical purposes is an innovative field: what do you think are the main challenges that must be overcome to make it a reliable and useful tool in everyday

«Voice analysis for clinical purposes is a fascinating but complex field. One of the first challenges is technical: the voice is a very rich signal, but it’s also extremely variable. It changes depending on the microphone used, ambient noise or even the person’s tiredness and mood. That’s why we will develop signal processing and machine learning algorithms that can increase the robustness of the analysis: starting with traditional techniques, such as the short-time Fourier transform, to capture the fundamental characteristics of a voice, the data is processed using neural networks. This allows us to extract representations that are less sensitive to external conditions. The challenge will lie in telling apart changes caused by external factors and changes that actually relate to each patient’s health.

Clinical validation is the second issue. For the voice to become a true diagnostic tool, we must perform studies on large and diverse samples to demonstrate that certain vocal patterns reliably correlate with clinical parameters and disease trends. Only in this way can we gain the trust of doctors and so find our place within their care practices.

Finally, there is a human dimension, and that’s fundamental: the patient must feel comfortable interacting with the avatar, perceiving it not as a substitute for the doctor but as a supporting tool. And even doctors will come to view it as an ally in simplifying monitoring. If we manage to overcome these three challenges – technical, clinical and relational – then we’ll truly be able to make use of the voice as a new health tool; one that’s both simple and powerful».

The project is founded upon collaboration between hospitals, universities and foundations: what does it mean for you to work in such an interdisciplinary context and what opportunities arise from it?

«For me, working in such an interdisciplinary team is a great opportunity both from a human and a scientific point of view. Politecnico di Milano is a prestigious institution, always at the cutting edge when it comes to developing new technologies, so we naturally come into contact with other leading national and international initiatives. AVATAR-SC is working with the Niguarda Hospital and the De Gasperis Foundation, two leading entities in the field of cardiology. Having the opportunity to support them means putting our technological skills at the service of those with the kind of daily hands-on clinical experience that gives them deep

That said, it isn’t totally out of the norm for me to come into contact with experts from other sectors, outside of engineering. In my research, I have worked with musicians and luthiers, people with a deeply artistic and creative vision. Now, I’m finding working with doctors and psychologists very stimulating because they bring a clinical approach that places people at the centre of it all. They are very different worlds and, I admit, sometimes it can feel as if we’re speaking different languages because everyone uses the jargon from their own sector and prioritises differently. But the added value lies precisely in these differences: bringing together such distant perspectives allows us to look at the problem in a new, more holistic way and to build solutions that none of us could have conceived alone.

This continuous exchange not only provides scientific progression, but also personal and cultural growth: it forces you to get out of your “bubble” and teaches you to translate your knowledge into something others can understand and make use of. That’s why I believe it is so important to run a project like AVATAR-SC and for us to keep developing and learning as researchers».

Looking ahead, what other promising applications do you envisage for these technologies and what are your research goals in the coming years?

«AVATAR-SC is only the first step along a path with enormous potential. There will be much to do in the coming years to make this approach truly effective, reliable and accessible, and I hope that the results will pave the way for other medical applications as well.

Sound and voice potentially contain a surprising amount of information, not only relating to physical state but also emotional state. I would therefore like to deepen the use of audio processing in medicine and rehabilitation, also exploring various types of signals, for example using music as a therapeutic tool and as a key to better understanding our emotions. This field really fascinates me because it combines my technical skills with the opportunity to have a direct impact on people’s wellbeing.

Another fundamental goal for me will be to continue working in multidisciplinary teams: working together with musicians, doctors and other professionals gives me continuous enrichment, and I believe it is the best way to turn research into tangible solutions.

I would like my research to continue along this path, finding new ways to bring science, art and health in contact with each other».