A website providing an in-depth and precise description of the inland areas of Lombardia went online a few weeks ago. Entitled Altre Lombardie, it is the most complete and extensive collection of data on peripheral areas in an Italian region, resulting from a collaboration between DAStU, the Department of Architecture and Urban Studies at the Politecnico di Milano, and the Lombardia Region General Directorate for Local Entities, Mountain and Small Municipalities. It details the characteristics and factors that make 14 areas peripheral. These range from Oltrepò Pavese to Valchiavenna, from Lomellina to Oltrepò Mantovano, and have resources to implement a local development strategy in the 2021–27 regional planning period. Based on quantitative data, maps, qualitative analysis, and interviews with local actors, it explains the uniqueness of these places and their difficulties due to their distance from large centres and services.

The impressive body of material, which is free to consult at www.altrelombardie.polimi.it, is the result of a process to involve local communities, with the organisation of 28 workshops which saw around 1600 participants, including hundreds of mayors. The results of the workshops were collected and organised into a strategic agenda for each inland area.

Fieldwork to collect data and interact with local communities began in 2021, with coordination by Professor Alessandro Coppola from DAStU.

Professor Coppola, could you define ‘inland areas’?

The criteria used to identify inland areas in Italy refer to their peripheral territorial conditions. The actual definition originated with the National Strategy for Inland Areas (SNAI), which was promoted by the Monti government, with Fabrizio Barca as Minister for Territorial Cohesion. According to SNAI, inland areas are situated far from what we could call service centres, based on a series of indicators.

SNAI relies on European funding from ERDF and ESF+. In Italy, the inland areas policy was first financed through a Partnership Agreement for the 2014–2020 period, and then refinanced for 2021–2027. Some regions, including Lombardy, also decided to identify other inland areas in addition to those under SNAI, using European programmes for financing.

Are the inland areas of Lombardia specific in any way compared to those in other regions?

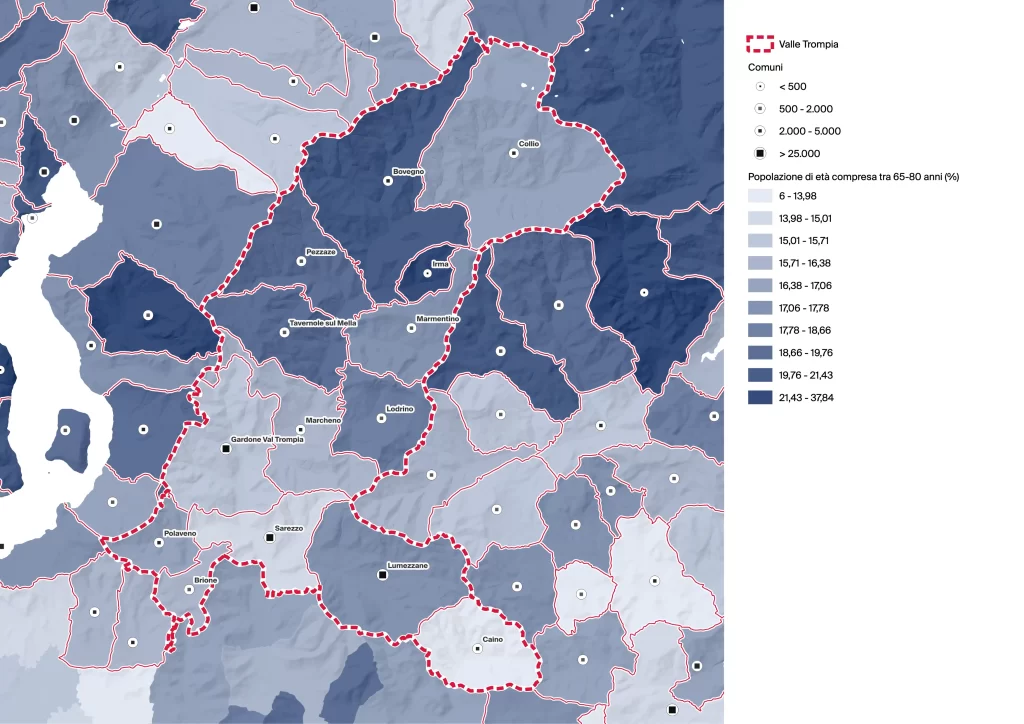

The conditions of territorial marginality in Lombardy are particular. Some of these areas include municipalities of a certain size with significant economic and production aspects or strong connections with large urban areas such as Bergamo and Brescia. Examples in this sense include Val Trompia, Val Camonica, or Val Seriana. Instead, the image we have of Italian inland areas are the Apennine valleys in the centre or south, which are much farther from large attractors. They do not have important urban areas nearby, and therefore experience severe economic weakness.

So are there any fixed criteria for defining inland areas?

The state has criteria — for example, the distance to a series of basic services, such as a railway station of a certain size, secondary schools, a hospital with a functioning emergency room. The Lombardy Region considers a broader range of indicators — demographics, economics, the environment — and has selected uniform areas with respect to governance, that is, within the perimeter of a mountain community, for example.

What do we mean by ‘depopulation’?

First of all, we must be clear that up to now, the population of a few of these areas has not been decreasing. In addition, there are various depopulation processes. When we processed the data, we came across areas with a positive migration balance, where more people are arriving than leaving. The problem is that this is not enough to compensate for the negative natural balance, that is, the difference between births and deaths. Some areas have a very negative natural balance and also a very negative migratory balance. Some areas, such as Oltrepò Pavese, are experiencing intense depopulation even though the migration balance is often positive. The conclusion is that depopulation is not the same everywhere, so it cannot always be treated equally.

The first part of the work — data collection and processing — highlighted the strong interdisciplinary aspect of the project. How are town planning, economics, and social and environmental policies entwined in building integrated, supra-municipal development strategies?

Our group included a sociologist, a geographer, several land and urban planners, and a conservation expert. And then, of course, there were specialists in different subjects among the town planners. For example, a colleague who is an expert in mobility worked with us on processing all the mobility aspects. Another urban planner who had more experience in housing dynamics worked a lot on the housing stock. The first part of the work was done according to speciality. Then two researchers ‘adopted’ an area and worked on it holistically. Beyond this, there was also real interaction with local actors — and their knowledge, which is often very deep-rooted and specialised — to cultivate the interdisciplinary nature of our work.

Let’s turn to the second phase, the strategic agendas. How did the existence of naturally limited resources from different lines of funding — European, national, and regional — condition their development?

This was a very long process. The project began in 2022 and all the material we produced was made accessible in 2024, but only recently did the Region approve the first strategy, the one for the Val Seriana. We were not responsible for working with local actors on the individual projects that each area included in their strategy based on the need for precise funding rules. Rather, we helped to construct the strategic agendas, that is, programming documents that organised medium-term visions, priorities, and content. For us, it was important that the actors in different territories felt free to discuss anything they felt was important, not just what could be done with specific funding sources. You might say that the document we delivered, which we developed with local actors, will theoretically live longer than the strategy built with the Lombardia Region, which instead serves to implement the available funding at that time.

And was it a fruitful choice?

Definitely. First of all, it allowed communities to focus on issues that were not very present in the initial planning — housing, for example.

Why is the issue of housing so important in territories at risk of depopulation?

There is very little available to rent in these areas, so it is very difficult to attract certain professional profiles, such as nurses and teachers, who may come from Southern Italy and plan to stay in the area for the duration of their contracts. The same applies to young people who have not yet decided where they actually want to live, and so are not sure whether they want to buy a house.

There is also the problem of overtourism, especially on Lake Iseo and the two shores of Lake Como. It is not a question of overpriced housing, as in Milan and other big cities, but rather a lack of rentals for people who already live in these municipalities, and also for those who have come to work in tourism.

We’ve talked about housing, but are there challenges or interests common to the 14 areas in question?

There are many, and they are intertwined. One issue is the gap in technical skills. The municipalities are often very small, and they hold competitions to hire technicians and professionals that go unanswered because the salaries are low and the location is difficult. Without joining together, these municipalities cannot remain attractive.

Then there is the issue of services. Commercial activities are abandoning small towns, the number of children is dropping — which undermines the widespread presence of schools — and the health service is struggling to find professionals.

There was talk everywhere of public transport, which is widespread in these areas, but often tailored to school needs. It is the children themselves who lose out, since they cannot travel by public transport to sports or recreational activities, or even to social venues. Low-income workers, who are commonly foreigners, are also affected as they often cannot afford a car. In this sense, the designs that emerged are flexible, maybe even on-call systems. Other territories are working to invest in old railway tracks, as is happening in the valleys around Bergamo.

How do you imagine the relationship between inland areas and large urban centres in the coming years?

This is a great topic. Some of these areas are already partially integrated into an urban system. One perfect example concerns the valleys around Brescia and Bergamo, which already have a very strong relationship with their respective capital city. Other areas, however, such as Valchiavenna or Oltrepò Pavese, are much more isolated from larger urban centres.

One future perspective for achieving greater territorial cohesion is to reorganise people’s lives around multiple locations. Lombardia has a large population and an even larger building stock, which is often empty or underused in inland areas. This heritage must be reactivated by making it possible for residents of urban areas to spend long periods of time in the inland areas at an affordable price. As climate change advances, this is a must for both public health and social justice. Doing so, however, requires public policies. The market alone would leave many properties unused or would select only certain social groups.

This cannot be the only aspect, of course, because otherwise the peripheral nature of these territories would be reproduced, becoming resort areas. In the future, I also see recognition of the fact that these areas produce essential ecosystem services such as mitigating extreme events, supporting the nutrient cycle, and regulating temperatures. We should start to consider these aspects, investing resources in people who care for the areas and can build life projects there as farmers, maintenance workers, environmental educators, and tour guides. The resources we invest in these areas are not only for welfare, but also serve the overall balance in the territory. Moreover, some of these valleys also have ancient industrial traditions that are still alive. For example, the Val Trompia has one of the highest rates of employment in manufacturing in Italy. In contrast to other places, these are also productive valleys, which would need significant investments to make the systems evolve to become environmentally and economically sustainable and innovative.

Strategies for Internal Areas: the DAStU’s Altre Lombardie project