For the 24th Triennale di Milano International Exhibition, the Politecnico di Milano has created an installation that uses artificial intelligence to make us experience the invisible folds of discrimination first hand. A job interview, three avatars, and five minutes expose our automatic behaviours.

There are experiences that you don’t just look at. They call you by name, ask you questions, make you uncomfortable. ‘Not For Her’ is one of them. Far from technology that makes decisions for us, the installation by the Politecnico di Milano reverses the perspective: AI not as a judge, but rather as a mirror. The device listens to words, reads facial expressions, and echoes our cultural biases in real time. In this interview, the installation curators, Professors Ilaria Bollati, Nicola Gatti, Matteo Ruta, and Umberto Tolino, talk about what it means to design a machine that builds awareness and why the most powerful innovations are sometimes those that ask us to stop for five minutes.

Concept developed by:

Donatella Sciuto, Rector

Installation curators:

Nicola Gatti, Scientific Director of FAIR (Future Artificial Intelligence Research)

Ingrid Paoletti, Rector’s Delegate for Exhibitions and Events

Matteo Ruta, Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering

Creative director:

Umberto Tolino, Vice Rector for Communication and Cultural Activities

Ilaria Bollati, Researcher in the Department of Design

How did ‘Not For Her’ come about and what was the initial challenge?

Matteo Ruta: The invitation for the Triennale reached the Rector of the Politecnico with a clear request: bring a project about artificial intelligence. We decided right away that it wouldn’t be an installation to watch, but rather one to experience, something interactive to make people identify with inequality and stimulate reflection.

Nicola Gatti: The stimulus was obvious: AI and discrimination. AI is usually accused of amplifying bias. We wanted to turn the narrative on its head and show that if it is designed well, it can do the opposite: make human prejudices visible and build awareness. We didn’t want to talk about a ‘bad’ type of technology, but rather build a useful system under human control.

Why did you choose to focus on gender?

Matteo Ruta: At the beginning, we looked at various forms of inequality (age, ethnicity, sexual orientation…). Then, due to the impact and clarity of the message, we decided to focus the project on gender discrimination. It was also a way to interact coherently with the overall itinerary of the Triennale. The topic of gender discrimination allowed us to dive in deep and elucidate the conflict in just a few minutes.

Ilaria Bollati: We wanted an urgent social issue to become an experience, not just content to watch. We chose a basic, measured arrangement that works by subtraction and makes room for empathy and accessibility. It conveys a clear, intense, legible message designed to let the eyes rest and accompany — but not overload — visitors arriving from an itinerary that is already full of stimuli, which is typical of a great international exhibition.

Umberto Tolino: It is also a crucial topic for an approach to technical and scientific studies. The focus on gender issues allowed us to draw on the polytechnic skills of the university to create a credible representation of the gap that often awaits students at the end of their academic careers.

How does your technology differ from traditional ‘interactive’ installations?

Nicola Gatti: It is not a tree of pre-filled answers. The dialogue grows out of each visitor’s actual words. A generative AI system interprets them and guides the conversation through a scenario while maintaining contextual consistency. It is an all-purpose, reprogrammable machine: change the content and you change the experience.

Ilaria Bollati: The technology is there. It works and we interact with it, but it doesn’t perform; it supports the experience and content. It is never an end in itself. It is meant to serve the message and those experiencing it. The system interacts with the voice, listens to the words, and reads the visitor’s facial expressions, modulating its response from time to time.

Umberto Tolino: The network-based datasets it uses are not opaque. They are curated by the professors and researchers, and the technology is adopted for cultural purposes. It holds a natural and credible conversation without exhibiting what makes this possible.

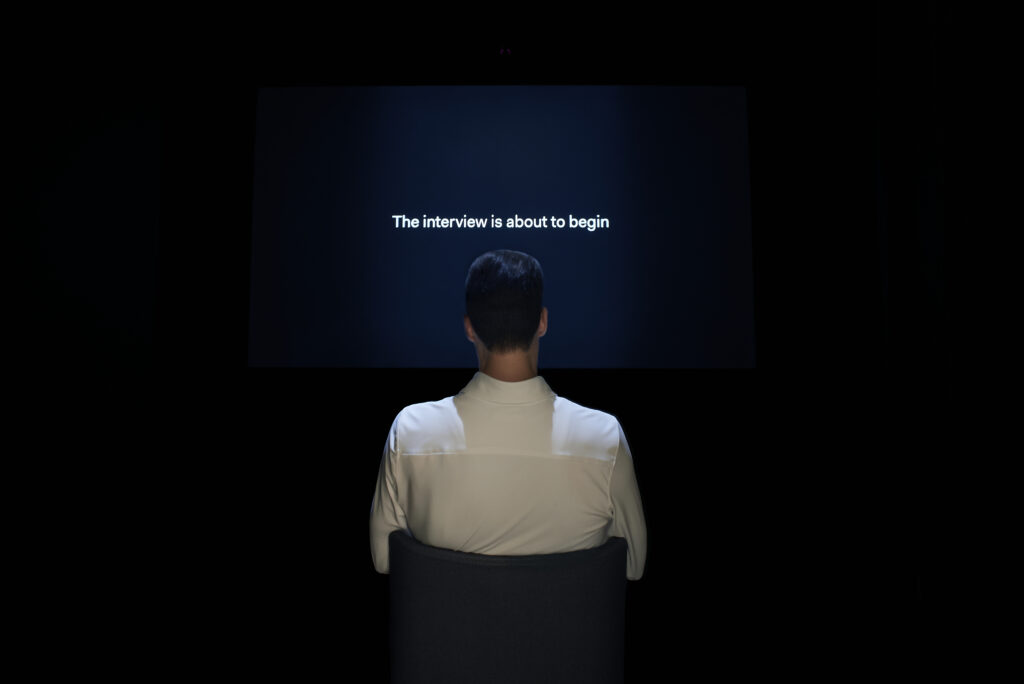

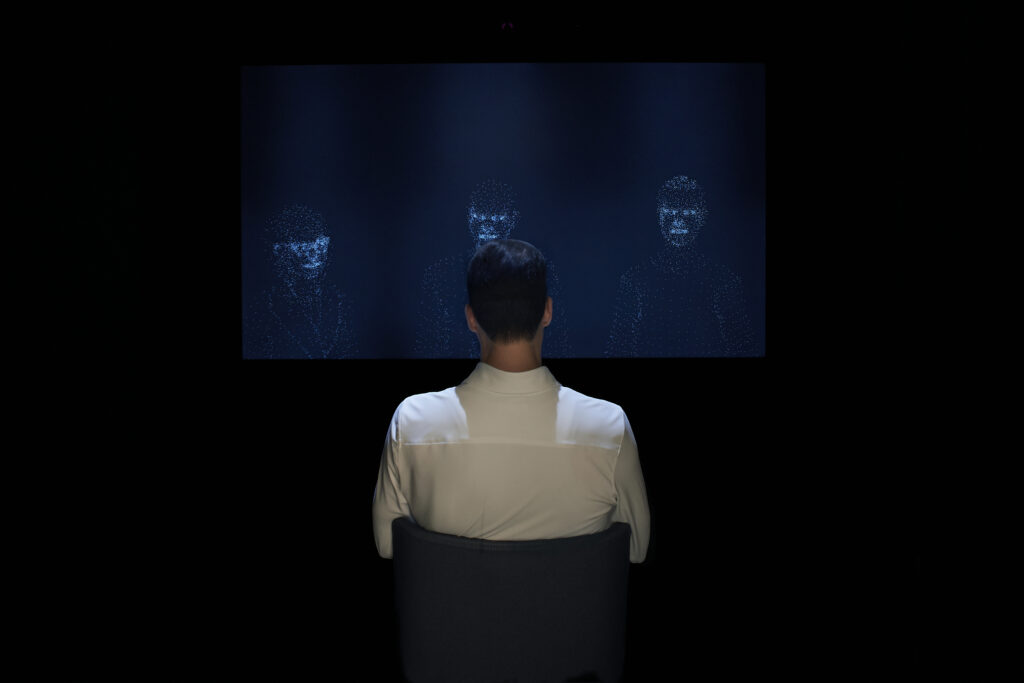

Matteo Ruta: The three avatars are deliberately ‘nuanced’ and not hyperrealistic. Their head and shoulders are positioned as if they were sitting at the same height as the visitor to promote a more natural setup. The room is dark for the audio and expression viewing to work. The system reads the emotions on the visitor’s face and calibrates the pressure of the conversation. If you hesitate, it presses; if you are already tense, it changes the tone.

What happens inside and outside the ‘cube’?

Ilaria Bollati: You enter through a translucent curtain, a threshold that separates and prepares the visitor. First, there is a discreet waiting area: neat seating, low tables, books to browse. It is an invitation to knowledge as a spontaneous gesture. At the back, the opacity of a mirrored wall increases, reflects, and then fades, alluding to the multiple unconscious filters and biases that cross our view of reality. Then you continue on. You sit in front of the three avatars, and the interview begins.

Matteo Ruta: We wanted everyone to have a unique experience. This is why the language changes constantly. Each person talks about a different experience. Inside, the feeling is deliberately unsettling. This serves to remove our filters and bring out what we really think.

Umberto Tolino: The experience is designed carefully. There is a natural interface and a few minutes to come to the point. At the end of the interview, we do not list the points of discrimination, but rather provide the user with a path for reflection.

What reactions have you observed? What are you learning from the data?

Nicola Gatti: The system listens to natural language and alternates who is speaking. It also uses the visitor’s facial expressions to recognize the emotional state and modulate pressure from the ‘committee’. Everything happens transparently for the person, but the data are anonymized and used only for research and to improve the experience.

Matteo Ruta: There is a striking fact: when a man has to unexpectedly ‘invent’ Sofia, he often imagines her as young, just out of university, and in a cultural setting. Even people who consider themselves to be sensitized discover that they have deep-seated automatic behaviours. This is precisely the mirror effect we were looking for.

Ilaria Bollati: In addition to the data, we also integrate the point of view of cultural mediators present in the room. Continuous, discreet observation of the audience gives us qualitative feedback for comparison with anonymous feedback from the conversations.

Umberto Tolino: The installation arouses more attention from women and bothers the men. This means that friction with such content works. It is not uncommon for men to choose not to enter at all, given the idea of the interview. This refusal is telling because it touches on recurring, well-known attitudes. We will analyse the final data carefully. In the meantime, the installation (physical and digital) offers points for interpretation and reading suggestions for those who want to learn more about the topics underlying the project.

How reprogrammable is this machine? And where will it go after the Triennale?

Nicola Gatti: The platform is modular. By changing the content and guiding rules, it can become a device for teaching, theatre, and other sorts of projects. It is not ‘the discrimination machine’. It is a machine that is talking about that topic today.

Matteo Ruta: From the beginning, we designed it to be portable, to give it a second life at the university and elsewhere. The data we collect will feed into scientific publications and open research that others can use.

Umberto Tolino: We want to enhance this work by extending the experience through public engagement events. This is a technological and cultural experiment that deserves other opportunities for dissemination.

What does ‘politecnico’s culture’ mean in a project like this?

Umberto Tolino: Engineering, design, architecture, dramaturgy, research on the content, and data: the project exists because all these skills came together. This is the style of the Politecnico di Milano, a cultural institution that designs by focusing on people: Technology for Humanity.

What has it given you, both personally and with respect to design?

Umberto Tolino: The gratification of a high-quality collective result. It is not an individual project, but one created by the entire institution. And it’s the joy of seeing technology, content, and space come together in unison.

Ilaria Bollati: The word that comes to mind is balance: between rigour and sensitivity, between openness to the public and remaining faithful to our scientific and polytechnic identity. It is multidisciplinary work by humans consisting of interaction and listening.

Matteo Ruta: On a personal level, it really struck me that I have dealt with these issues for years and I thought I was ‘ready’… and then you realize how deep the rabbit hole is. Automatic behaviours remain and there is still so much to do. Sometimes it can even leave you feeling down. It is important for us to talk about these issues and that we do it well.

Not For Her’ proves that artificial intelligence can be an ally in civic education. The silence of a dark room, three avatars, and five minutes of conversation are enough to make us stumble upon our prejudices. It doesn’t preach; it tests you. And when you leave, the questions go with you. This is where innovation and awareness truly begin.