During his Politecnico di Milano lecture “The Egyptian Museum 200 Years Later”, Turin Egyptian Museum Director, Christian Greco spoke to Frontiere about archaeology, technology and the dissemination of culture. In exploring partnerships, the trials of digitalisation, and the vision of the museum as a meeting ground, the discussion reveals a consideration of culture’s role in modern life.

Dr Greco, could you tell us about the Egyptian Museum and Politecnico di Milano partnership? When did it begin, and what has it achieved?

Our partnership with Politecnico di Milano is well established and dates to 2018, when Politecnico first took part in our excavation work. Its main contribution has been in photogrammetry, which has enabled us to document the excavation in detail and create three-dimensional models. These models allow us to “relive” the excavation even remotely, analysing the stratigraphic structure with greater accuracy.

We have produced 3D representations of the walkable surfaces and underground structures. Such documentation has immense scientific and cultural value. It ensures that knowledge of these monuments is preserved for future generations and allows us to study the tombs’ layout, their structural relationships and evolution.

Could you give us some examples of this partnership?

Certainly. In Deir al-Medina, Politecnico documented the shaft and burial chamber of Kha’s tomb, located 29 metres north of the chapel. They modelled the remains in situ and reconstructed the mudbrick pyramid that once stood above the chapel, surmounted by a stone pyramidion which is now in the Louvre. Politecnico modelled the pyramidion directly in the Paris Museum.

This synergy between digital technology and archaeology allows us to reassemble “membra disiecta”, to reunite objects dispersed across different collections and restore them to their original context.

Did Politecnico play a role in the Museum’s digitisation?

Yes. Professor Corinna Rossi was instrumental in our digital transition. She is a member of our digital commission and contributed to the development of bespoke software called SiME, which manages our artefacts inventory. This system integrates management data, restoration records, archival documentation, diagnostic information and imagery, creating a research tool that reflects the unique nature of our museum.

Why was it necessary to develop customised software?

The Egyptian Museum is a monographic institution, dedicated exclusively to ancient Egypt’s material culture. Generic software does not meet our needs.

For example, how should a mummy be classified, as an object or as human remains? We needed to establish ontological definitions that represent our artefacts accurately and relate them meaningfully to one another.

You have often spoken of the need to contextualise the artefacts. How far along is that process?

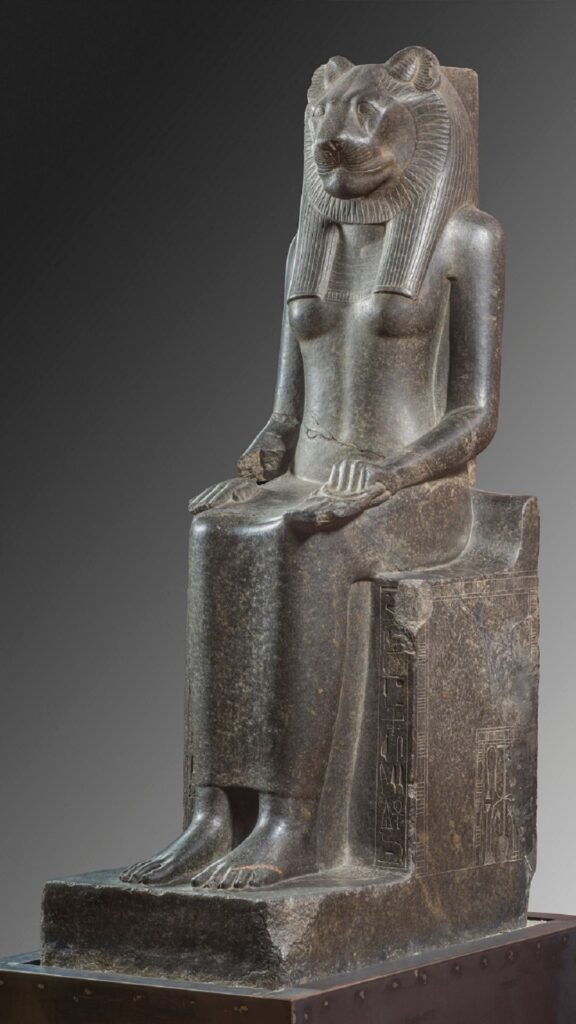

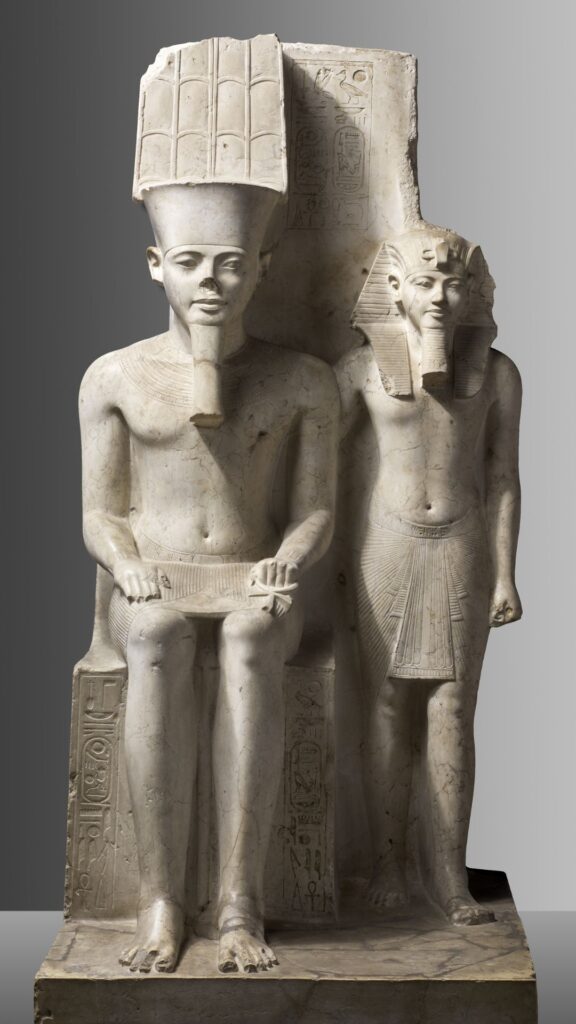

We are witnessing the beginning of a new age for archaeological museums. An artefact is no longer seen as an isolated work of art but as a memory fragment. We must move beyond the object to reconstruct the cultural landscape in which it belonged, where each artefact forms part of a greater whole. This approach transforms the museum into a space for dialogue and reflection.

You have said there is no such thing as shared memory. What do you mean by that?

The Egyptian Museum may represent national pride for Italians, yet others may view it as the product of a Eurocentric outlook that appropriated cultural heritage. These perspectives do not easily converge. Our responsibility is to ensure that the museum becomes a safe space for dialogue, where differing views can be expressed and respected.

So, the museum becomes an agora?

Exactly. The museum should be a public space where we speak with one another, not only about others. Even in Italian history, not all dates have the same meaning for everyone. But that’s not a problem. We can interpret memory differently, provided we engage in dialogue.

How is the Egyptian Museum’s renovation progressing?

We are confident it will be completed by summer 2026.

How did your passion for Egyptology begin?

It started when I was 12 years old, during a trip to Egypt with my mother. On the return journey, she asked if I had enjoyed it, and I replied: “I want to be an Egyptologist.” In secondary school, I read Schliemann’s account of the discovery of Troy, which captivated me. At classical high school, I developed a love for Greece, but Egypt remained my first love.

What does ancient Egypt teach us?

Studying ancient civilisations helps us feel less alone. It brings us together and reminds us that, despite technological progress, the great existential questions remain: death, illness, and suffering. Exploring the ancient world allows us to understand the roots of our existence. If today we are writing page 2025 of history, we must know the 6,000 pages that came before it.

How do you keep believing in culture, despite the challenges?

I consider myself lucky. I have the world’s most rewarding job. I had the chance to fulfil my dream, while many talented young people are still waiting. My strength comes from my passion for Egyptology and firm belief in the essential importance of this discipline.

This conversation with Christian Greco revealed a director driven by passion, firmly convinced of culture’s role as a catalyst for dialogue and collective progress. Under his guidance, the Turin Egyptian Museum is the custodian of an ancient legacy, a hub for innovation and a space for critical reflection on contemporary issues.