Roberto Dulio, Associate Professor of Architectural History at the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering, explains how Steinberg’s story links to Politecnico di Milano.

Who was Saul Steinberg?

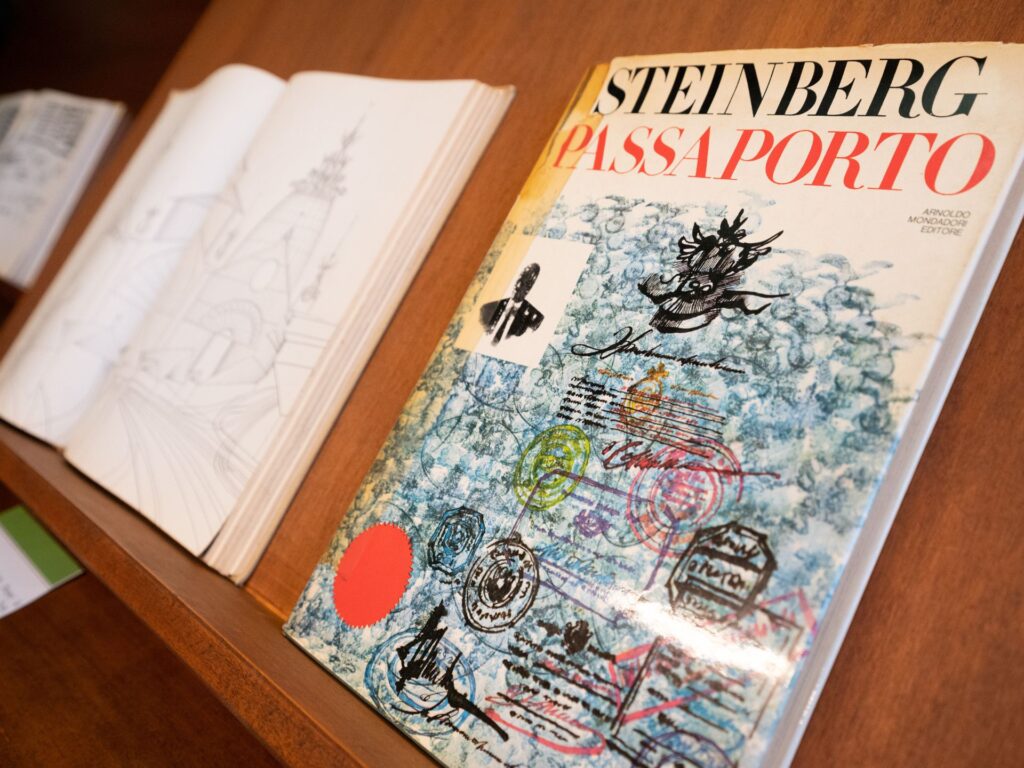

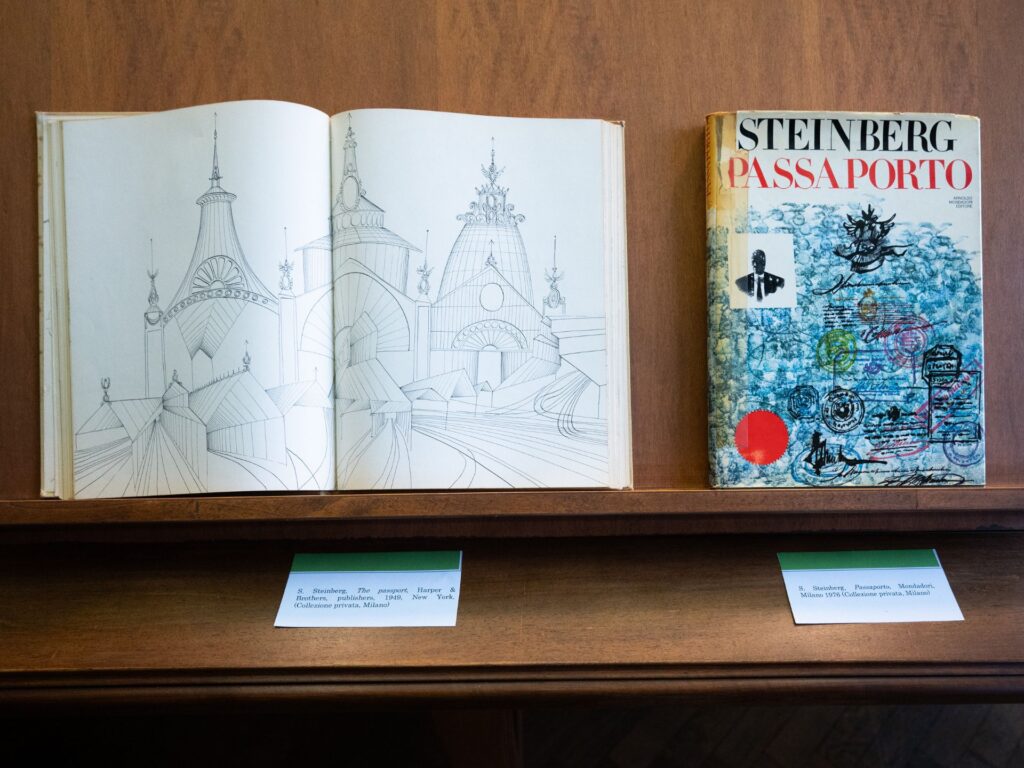

Saul Steinberg was one of the most internationally renowned artists to have studied at Politecnico. He was knows as an illustrator, but recent exhibitions, such as one at the Triennale, have confirmed his status as an artist of real range and significance.

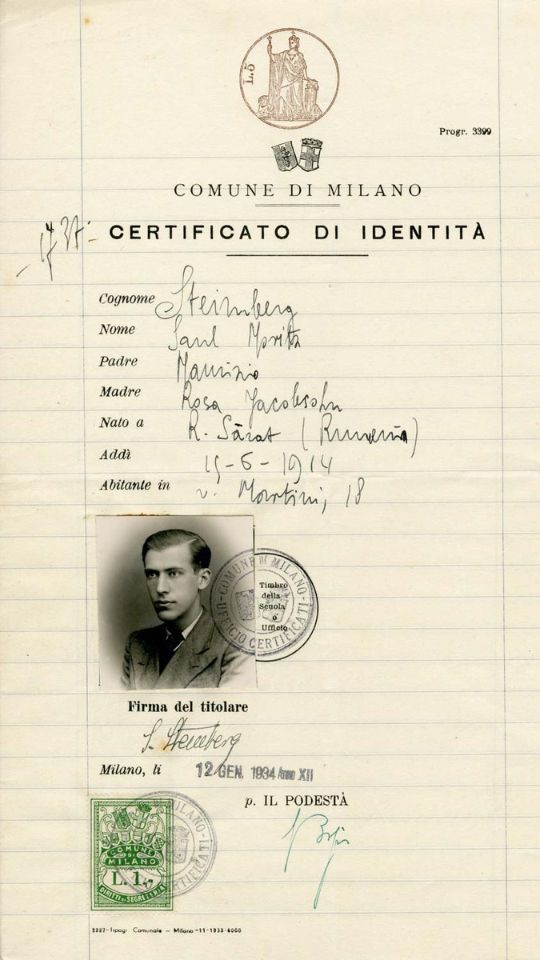

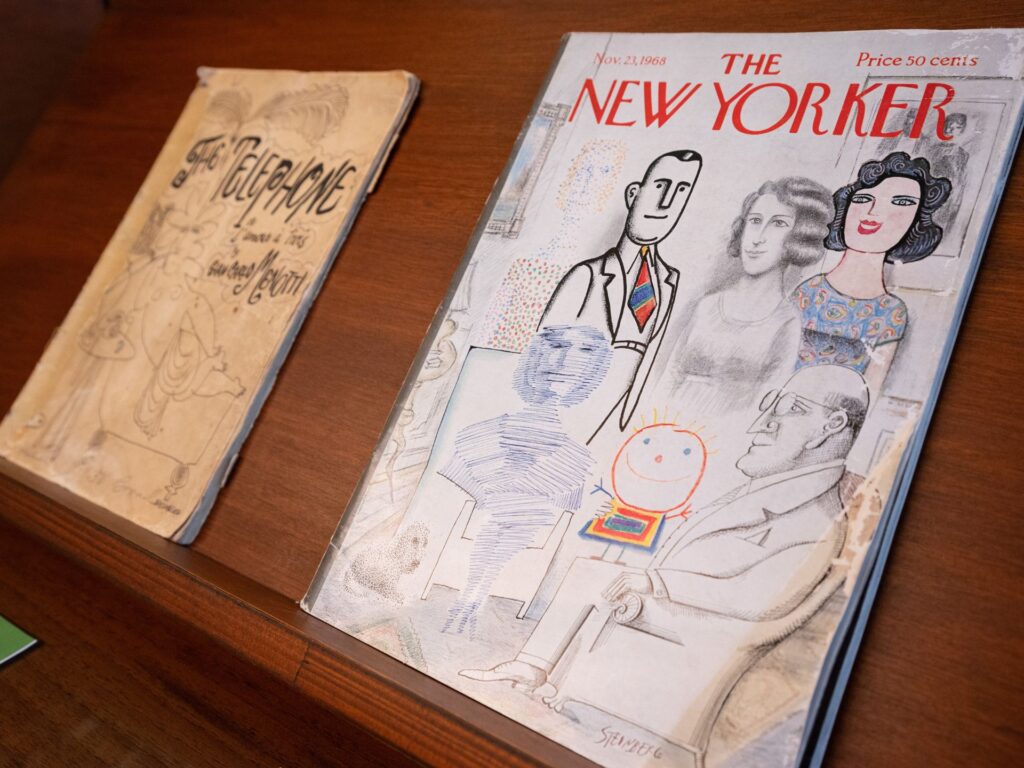

Although not American, Steinberg gained fame for his satirical The New Yorker covers and illustrations. Born in Romania, he moved to Italy in 1933 to enrol at the Faculty of Architecture at Politecnico di Milano.

What role did Politecnico di Milano play in his story?

At Politecnico, Steinberg met Piero Portaluppi, then professor and Dean of Architecture.

Portaluppi was a celebrated architect and a prolific satirical illustrator. He published cartoons in the weekly magazine Il Guerin Meschino. This satirical streak likely captivated the young Steinberg, who was an avid reader of humour magazines such as Bertoldo and Settebello.

As a student of architecture, Steinberg soon began producing his own satirical drawings. These works were conceptual in nature and not reliant on punchlines. He was influenced by leading illustrators working for Bertoldo at the time, such as Giacinto “Giaci” Mondaini (father of actress Sandra Mondaini), who was a painter and illustrator. Steinberg’s early drawings strongly resemble Mondaini’s style. Mondaini lived in the same neighbourhood as Steinberg, who, at least initially, resided in the university halls of residence (Casa dello Studente). Later, he shared various flats with fellow students, never straying far from the Città Studi district.

When did Steinberg, as an architecture student, begin working as an illustrator?

Steinberg published his first cartoon in Bertoldo in 1936. He brought a drawing to the editorial office, which, impressed by his unique style, decided to publish it. Interestingly, for this debut piece he signed himself “Xavier”, a pseudonym he would never use again.

His collaboration with Bertoldo, and later Settebello, brought him financial stability and success. This was an improvement over his earlier hardships as a student.

He left Casa dello Studente and began renting flats with friends. While waiting for his visa in Santo Domingo, he created a detailed list of all his past addresses, including dates and housemates.

Thus began his career as an illustrator, and with it, his decision to abandon his studies and exams. Everything was going well for Steinberg until the 1938 Italian Racial Laws forced him to realise that Milan, the city he loved and considered home, no longer accepted him. Though Romanian by birth, he strongly identified as Italian.

The racial laws, his work, and how he earned his architecture degree thanks to a loophole.

Despite the racial laws, Steinberg continued to publish his drawings anonymously. He contributed to the magazine Stile, founded and edited by Gio Ponti, another Politecnico alumnus in architecture. It is probable that Ponti played a key role in facilitating Steinberg’s commission to design decorative elements for furnishings at Fontanarte. Steinberg worked with other Jewish architects and served a primarily Jewish clientele, as this reflected the opportunities available to him during that period.

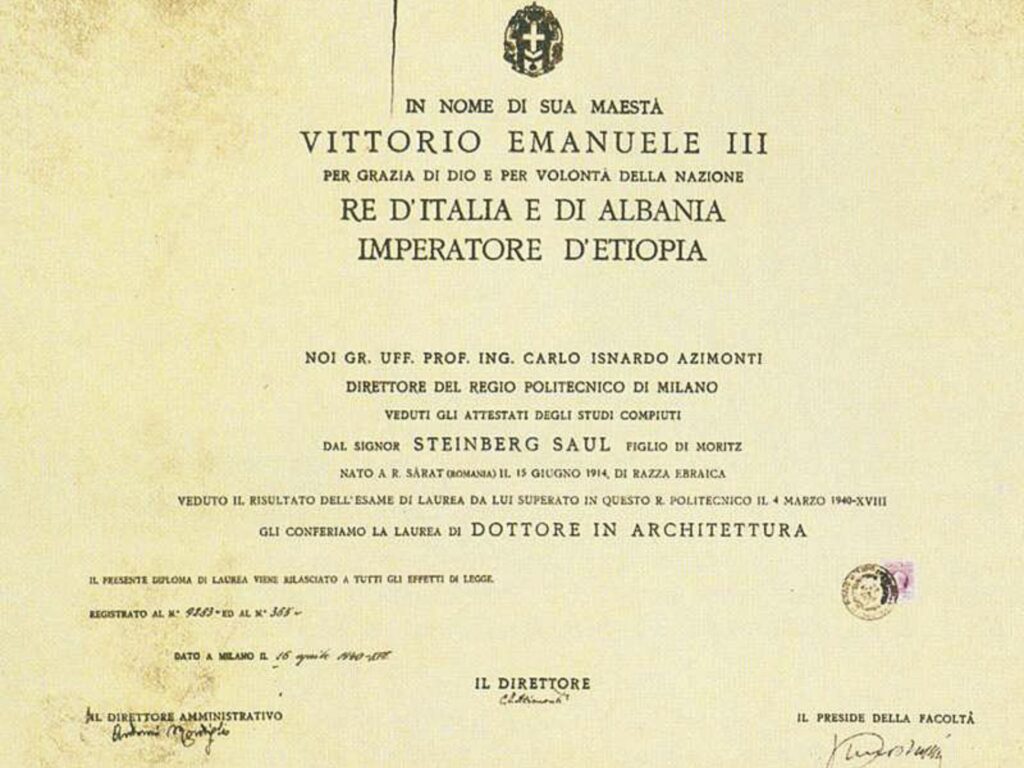

He began considering leaving Italy, but he had not yet graduated. Portaluppi’s support enabled Steinberg to use a legal loophole to earn his Politecnico degree. Under the racial laws, Jewish students were required to leave by the end of the 1938–39 academic year. An exception permitted those who had finished their studies to graduate during deferred sessions for that year. Steinberg received his degree under this exception.

Likely prompted by Portaluppi, Steinberg completed his remaining exams in a 1938 make-up session and graduated in architecture in 1940. With this degree, (one copy retained by Politecnico and another formerly exhibited in Steinberg’s New York studio) the artist could prepare for departure from Italy.

The unsettling detail on his degree certificate, kept at Politecnico

Aldo Buzzi, Steinberg’s friend and fellow architecture student at Politecnico, recalled an episode that reveals much about Steinberg’s ironic worldview. Looking at the copy of his degree certificate in his New York studio, Steinberg reportedly remarked: “This diploma says: In the name of His Majesty, King Victor Emmanuel, who no longer exists; In the name of the King of Italy, of Albania, and Emperor of Ethiopia, an empire that no longer exists. I am granted the title of architect, a profession I have never practised. But then, in bold letters below, it says: Saul Steinberg, of the Jewish race. So, in the end, it’s a diploma in Judaism.” It was with this mix of irony and bitterness that Steinberg addressed the trauma he experienced.

Saul Steinberg leaves Italy for New York

After graduating, Steinberg attempted to leave Italy, but due a series of unfortunate events, such as expired documents, spending time in San Vittore and an internment camp in Roseto degli Abruzzi, his first attempt to flee failed. In 1941, with the help of Cesare Civita he successfully emigrated to the United States. Cesare Civita was a copyright lawyer who played a key role in the publishing world, including convincing Arnoldo Mondadori to acquire the Italian rights to Disney material from a small Italian publishing house. Civita, an Italian American, emigrated to the US at the onset of the racial laws. In the US Civita managed to get Steinberg’s drawings published, before the artist’s arrival.

Working for The New Yorker

After arriving in the US, Steinberg started his long association with The New Yorker. Like many European émigrés, he joined the military through a programme that enlisted educated refugees to promote American culture in post-war Europe, foreshadowing the Cold War. Steinberg served in China, returned to Italy before the war ended, and reunited with lifelong friend Aldo Buzzi.

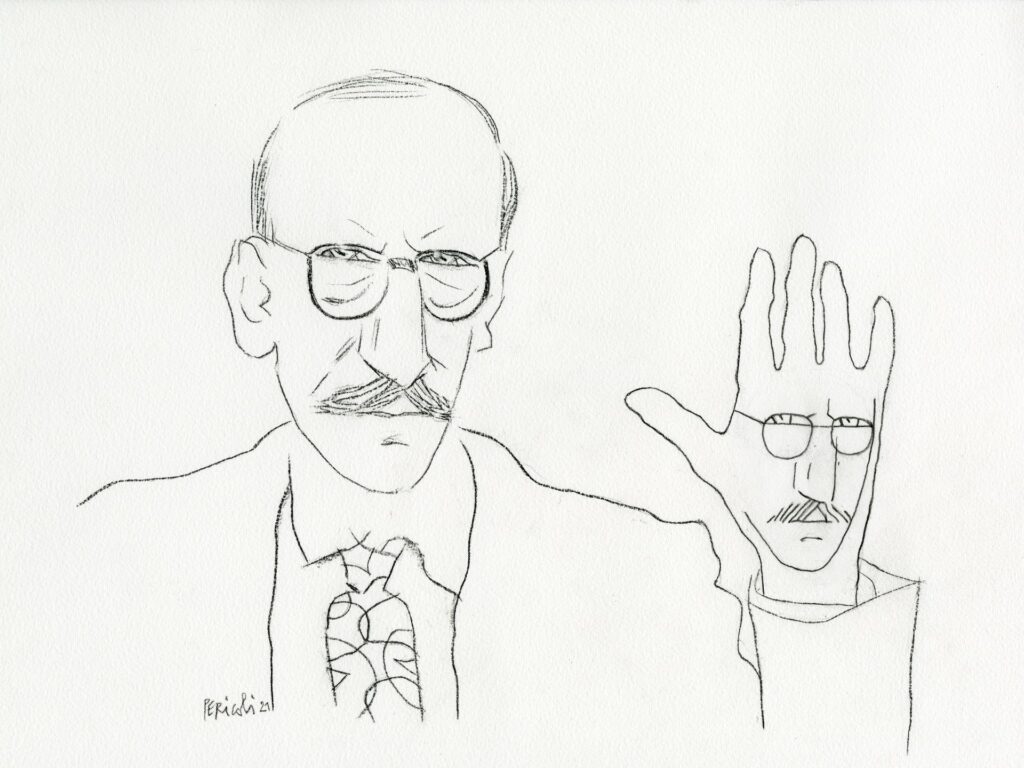

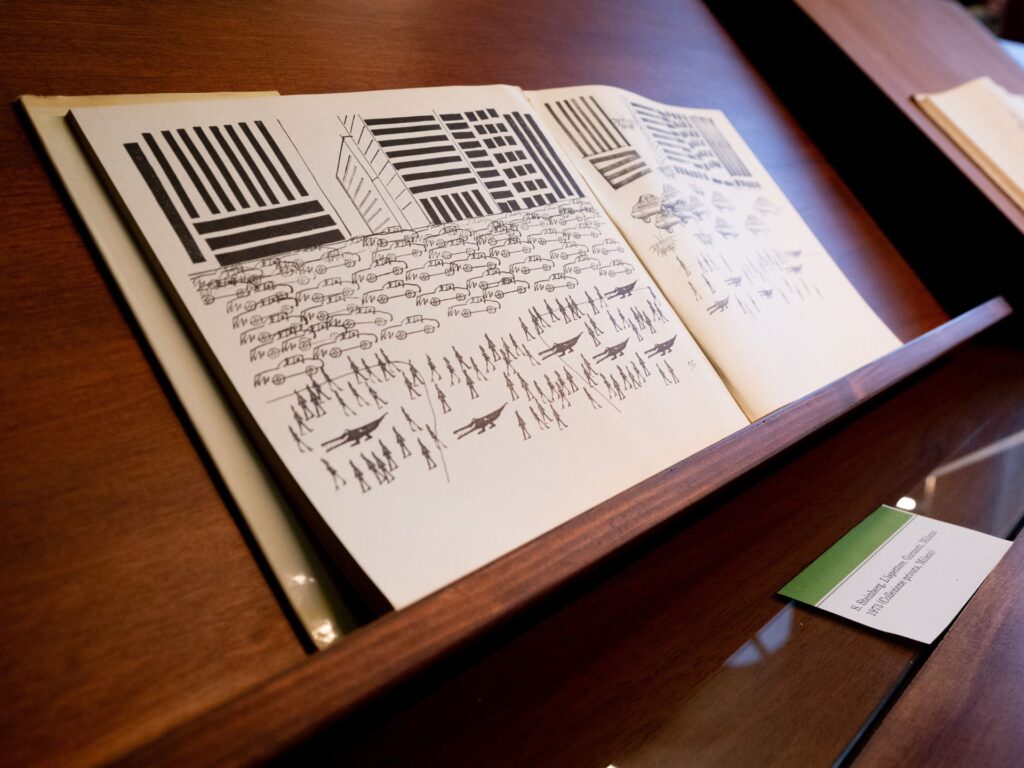

After the war, Steinberg’s reputation grew, with his illustrations featured in The New Yorker and other leading international publications. It was during this period that his artistic career took on a new dimension: His style became instantly recognisable. Tullio Pericoli claimed that, in the visual imagination of the 20th century, Steinberg’s style was as recognisable as Picasso’s. Even those unfamiliar with Steinberg’s name will recognise his trademark little figures, even if they don’t recall where they’ve seen them.

A complex and contradictory relationship with Italy.

Steinberg maintained lifelong ties to Italy, often returning to Milan to stay connected with Aldo Buzzi and other Politecnico-trained intellectuals who had chosen different paths. Il Bertoldo, the satirical publication to which Steinberg contributed significantly, emerged as a focal point for cultural discourse in Milan. Cesare Zavattini, a leading neorealist screenwriter and director, played a central role in that environment and was previously editor of Il Bertoldo, despite not being an architect.

For Steinberg, Italy remained a complex, contradictory memory, one of his happiest times, yet tainted by the shame of coexisting with fascism.

This contradiction is demonstrated by a relevant anecdote. A young art historian, and colleague’s son, conducted his university thesis on Steinberg, cataloguing more than 200 of the artist’s early drawings for Il Bertoldo. Excited, he travelled to New York to meet his idol. But Steinberg received him coldly. The artist had no interest in revisiting the works he had produced during the fascist years, perhaps because they recalled a troubling and embarrassing chapter of his past. Bluntly, he told the young man never to show those drawings to anyone.

A prominent international art leader closely connected to Politecnico.

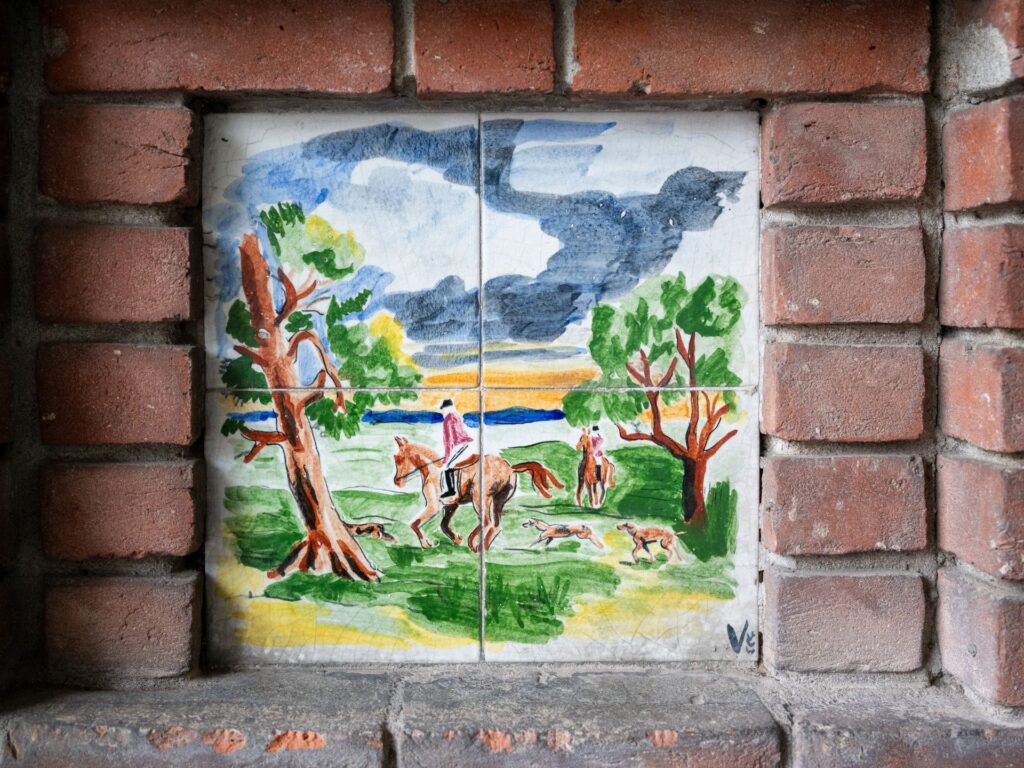

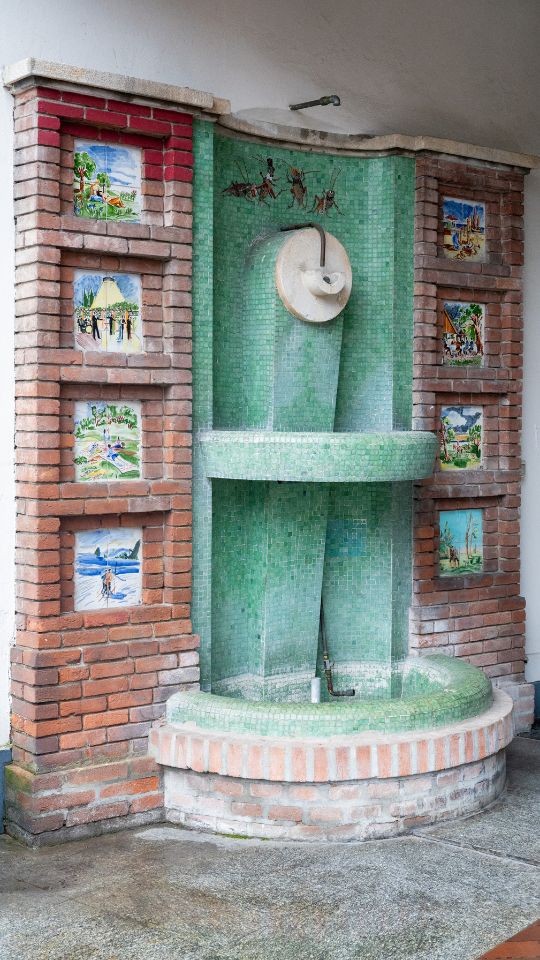

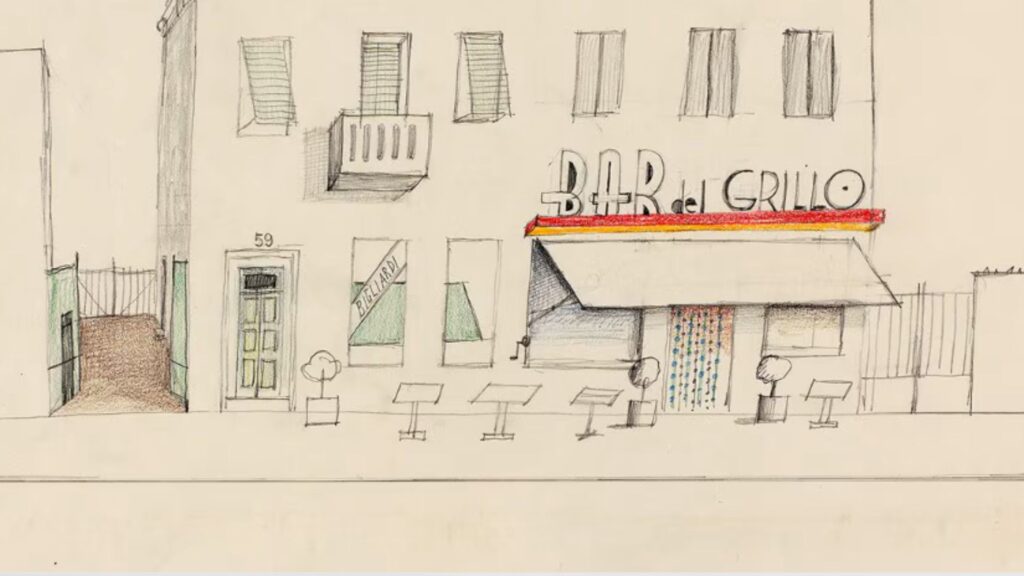

Steinberg was an architect who never practised, yet his training is evident in his work, in the way he drew, peered inside buildings, and dissected them. He even cross-sectioned trams and buses like dollhouses, which was a method shaped by his architectural background. During the 1980s, Politecnico selected his illustrations of the Bar del Grillo as the official poster image for its academic programme.

Città Studi, Steinberg’s Milan

For Steinberg, Milan meant Città Studi, and he rarely ventured outside its boundaries. In Città Studi, where the Cortina Bookstore is currently located, the Bar del Grillo was present until the 1990s and was a place he often visited. The bar’s interior was a youthful project of BBPR, a collective of four Italian architects, Gian Luigi Banfi, Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso, Enrico Peressutti, and Ernesto Nathan Rogers, who graduated from Politecnico and formed their group in 1932. The bar contained a billiards room and several private rooms. Steinberg rented one of the private rooms for his personal use

The Bar del Grillo held symbolic significance for him. In the 1970s, Steinberg drew four Milan scenes for The New Yorker: one of the Palazzo di Giustizia with a tram marked Lambrate, another depicting the church at the corner of Via Ampère and Piazza Leonardo da Vinci, and a third showing a tree-lined Via Pacini.

The fourth was Bar del Grillo, which later served as the cover image for the Politecnico’s academic programme. These 1970s drawings reflect his 1930s memories. Published in The New Yorker. Some now reside at the Biblioteca Braidense after a donation of more than a hundred drawings from the Saul Steinberg Foundation.

Politecnico and the racial laws.

Like every other university, Politecnico enforced the Fascist racial laws. During the German occupation, Rector Gino Cassinis opposed Nazism and Fascism by supporting the underground resistance.

Politecnico’s Historical Archives show that Fascist laws were enforced, but reveal instances where they were bypassed. These undercurrents of humanity allowed some to survive. This does not reduce responsibility for Fascism. However, the environment in Milan, and more generally across Italy, was more complex compared to the strict ideological consistency observed in Nazi Germany.

Professor Dulio, as a Politecnico professor and Steinberg enthusiast, what would you ask him if you met him?

I’m aware of many things about him, including his difficult personality, he wasn’t very charming. He was known for being reserved and melancholic. Maybe I would just give him a hug, considering that his thoughts and feelings are evident in his work. He probably wouldn’t have appreciated the hug. Steinberg had a deep sense of modesty, even about his emotions. So, asking him a question would feel intrusive, and almost violent. But a silent, heartfelt embrace seems more human. Or even just the idea of a hug.

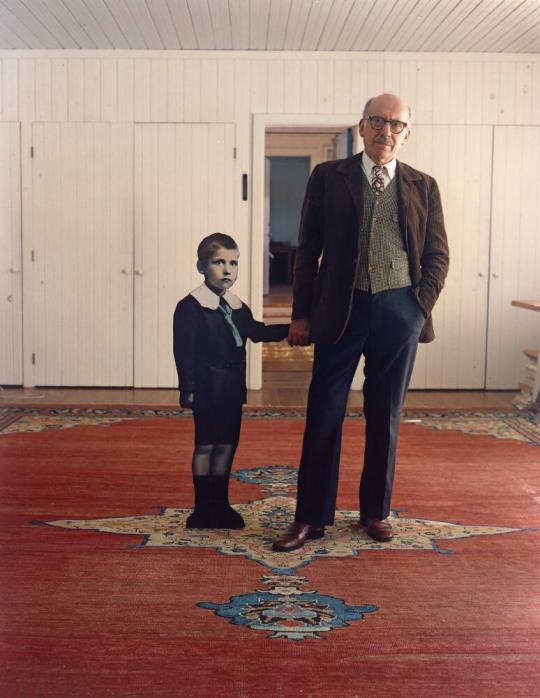

Can you provide one last image to close this poignant story?

I’ll end with an image that has always moved me. Steinberg struggled with his identity, family, and self. He enlarged a childhood photo into a life-size cutout, set it up in his New York living room, and had someone photograph him holding its hand. The image powerfully suggests someone so isolated that, looking back, he wished he could comfort his younger self.