Ernesto Colnago is a legendary figure in the world of cycling, one of the most innovative and influential builders of racing bicycles. A leading figure in the design, construction and testing of road and racing bike frames, he has made an immeasurable contribution to the industry.

This is why the Politecnico di Milano decided to award him an Honorary Degree in Mechanical Engineering. On 8 May, at the age of 93, Colnago received the latest of his many lifetime achievement awards, earning him the honorary title ‘Ingegner Colnago’ (Engineer Colnago).

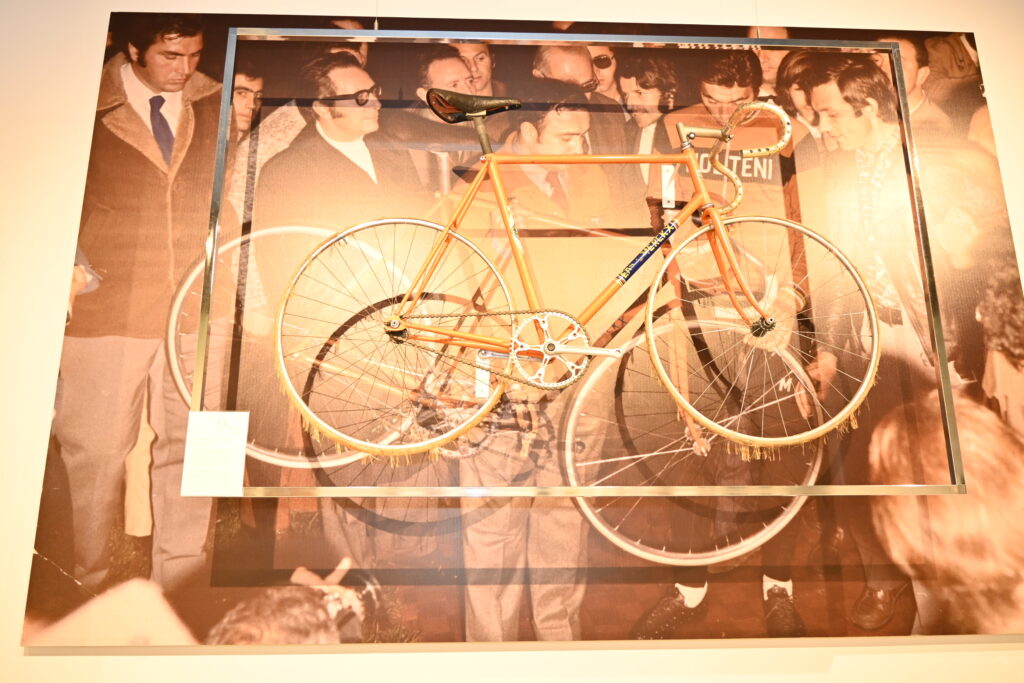

We at Frontiere visited him at the museum he has established in Cambiago, in the province of Milan. ‘La Collezione’ houses 80 two-wheeled masterpieces, 400 photographs and installations, and 80 racing shirts, all within a 1,000-square-metre space. It was an honour, a pleasure and an emotional experience to speak with him.

Mr Colnago, how did your story begin?

It started when I was 13, and I ‘falsified’ my papers by a year so I could go to work.

Let me explain: we were the children of farmers. I helped out during the day, and I completed the first and second years of middle school as a private student. Then, one day, I told my father that farming wasn’t the job for me. So I looked for a workshop in the village where they repaired tractors and bicycles, anything that involved welding. In effect, I started working to learn a bit about welding.

How did your father take it?

My father said to me: ‘Do whatever you want’.

But to keep me on, they wanted two kilos of cornmeal a week because they couldn’t ‘put me on the books’ [i.e. officially employ me – Ed.]. That’s how I learned about life.

A good welder at work said to me: ‘At Gloria, we don’t mess around!’ I said, ‘For goodness sake, what do I need to do?’ I’d set up a frame, and he’d weld the two pieces together. Basically, I was the ‘pinella’ [i.e. the apprentice – Ed.]. I came home the next day feeling less than happy…

Any stories from that time?

It was 25 November, snowing. There was no heating in the factory and the windows were open. I was only 13. A newly hired youngster, a few years older than me, came up behind me and kicked me in the backside.

I chased after him, thinking, ‘I’ll give you one too’, but he was faster than me. And do you know why? Because he would go on to become an Olympic boxing champion in London in 1948. His name was Ernesto Formenti. Get it? That’s why he was faster than me!

And your passion for cycling?

I transferred to the assembly department, and there I found my true calling. I truly fell in love with it. There were a few amateur riders at Gloria and I was curious because I liked racing, too.

After a few years, I began to win a few races. I rode the Milan–Busseto as an amateur and came off right outside Giuseppe Verdi’s house. I finished fourth or fifth, but after the finish line, I crashed into a Guzzino moped and fractured my right fibula. They brought me home and then to the hospital, where they put a board under my leg, bandaged it, applied a plaster cast, and told me to stay like that for 45, even 60 days.

And what happened then?

What can a 19-year-old lad do at home, stuck like that? I called my friend Luigi, who worked with me, and asked him to check with Mr Focesi, the owner, if he could send me some wheels to assemble at home so that I could lace and true them with my leg kept straight.

They sent the material over, and my father was alarmed: ‘Where are you going to put all those rims?’ I said: ‘Dad, just bear with me for two weeks, then I’ll go back to work.’

In five days, I earned as much as I would in a month. I realised that I had something inside me, something I was doing with love and great satisfaction.

But when the second delivery arrived, my father said: ‘Either we go, or you go!’ And I went. It was 1954

Is that how the Colnago story began?

I found a place on the main street in Cambiago, a dirt road back. Just imagine what it was like after the war! We were all poor, but we were all content with what we had.

The space was five metres by five, right across from the village’s main tavern. That’s where I started repairing bikes and assembling wheels. Then, one day, my old boss at Gloria, Alfredo Focesi, came to see me and said: ‘Where are you working? Here! I’m scared – that took real guts!’ So I said: ‘Let’s do this: you give me 25 special bikes a week to assemble. I don’t want any money.’ ‘So, you’ll work for free?’ ‘I don’t want money, I want materials.’

That way, the materials cost me nothing; only the effort of working day and night. With those materials, I repaired the bikes of my rider friends and local farmers. It was all profit, but I worked non-stop!

When did the breakthrough come?

I was lucky enough one day to run into Fiorenzo Magni while he was out cycling. We stopped for a drink. He was due to start the Giro d’Italia from Milan in three days.

He said to me: ‘I’ve got my new bike, but it hurts my leg.’ I took a look and said: ‘Signor Fiorenzo, do you know why your leg hurts? It’s because the pedalling isn’t round, it’s oval.’ He said: ‘I’ll go and see my mechanic.’ But Albani and Martini persuaded him to stop by my place instead. When he saw my little shed, a five-by-five-metre space with a chimney, he said: ‘You work here? I’m not bringing my bikes here! This place is a dump!’ ‘Please, Fiorenzo, bear with us,’ the riders pleaded. So I set to work and changed the two cotter pins, which was a joy for me.

And just like that, the pain in his leg disappeared.

He went on to race the Giro della Brianza, and that evening he sent his masseur to tell me: ‘Go and see him tomorrow morning, he wants to speak to you.’ I didn’t sleep a wink that night.

We jointly owned a Garelli Mosquito moped with the tavern across from us. With that, I rode to see him in Monza, where he said to me: ‘Do you want to come to the Giro d’Italia? I can see you’re good. I’ll give you food and a place to sleep – that’s it.’

That was how it all started.

I went to Masi, who was Magni’s mechanic. When I got there, being a typical Tuscan, he started swearing before I could even say anything: ‘We don’t fix mopeds here!’ But his worker told him to hear me out. Then he said: ‘I need a grown man. I’ve got to assemble 45 wheels by tomorrow. But who’s going to build them?’ ‘I will!’ I replied.

The next morning, I started at ten, and by seven-thirty or eight in the evening, I had built and trued 45 wheels.

I became his man! But only for a bit…

So, how did the Giro go?

I went ahead and did the Giro d’Italia. And Magni won the Giro!

The second year, I went with him again as a mechanic with Nivea. He came second that time because he broke his shoulder.

In the third year, Nivea was no longer competing, so we moved to Chlorodont, the toothpaste brand.

I built a new bike for Nencini. He liked it and went on to win the Giro d’Italia. But it had the Leo logo on it because I didn’t have my brand yet. When the owner, Mastracchi, asked me why, I told him honestly: I didn’t have one because I’d just made the bike for him.

After that, I joined Molteni. And I was lucky enough to have Dancelli, Motta, Altig… Then came Merckx.

How did your logo come about?

‘When Dancelli won Milan–Sanremo with Molteni, the first Italian to win in 17 years, we were in a restaurant that evening. Bruno Raschi, the editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport – one of Italy’s finest sportswriters – wrote: ‘Sanremo glory for Dancelli, riding a bike built by his mechanic, Colnago.’

Then he asked me to wait so we could have dinner together, during which he said: ‘You need to register an ace of clubs.’ I told him, ‘We’re not in Tuscany.’ He laughed and said: ‘No, in Tuscany, it’s a lily. Register the ace of clubs, it’ll bring you luck!’

And from there, we kept going forward. We won so many races.

What was your biggest challenge?

Back then, carbon fibre wasn’t used yet. Bikes were made of steel or aluminium. Then came titanium. But I’ve always been a researcher, so I tried to find a way to meet Enzo Ferrari.

It wasn’t easy to get the appointment. When I arrived, he was already seated, and I was at the head of the table. I explained to him what I wanted to do: build a carbon fibre bike.

He called in his four top engineers – one of them even used a Colnago bike, imagine that!

Ferrari said: ‘It’s impossible but I believe in him. He’s young. How old are you?’

I hadn’t realised I was talking to a man in his eighties, so I said: ‘Oh, quite a few!’ ‘How many?’ ‘Fifty-four.’ Then he banged his hand on the table and said: ‘Shame on you! I started building Ferrari at your age! And to pay five workers, I had to pawn my belongings: to pay five workers! Get it? Don’t be afraid. If I were your age, I’d walk from Maranello to Rome! I’ll help you.’

And that’s how the carbon fibre challenge began.

It wasn’t a walk in the park…

No, it wasn’t easy, because I spent a couple of years doing research. The Politecnico conducted all the vibration and oscillation tests to identify and resolve the issues.

All this to build a frame that weighed half as much as a steel one. I managed the entire process and built the carbon bike!

There had never been a bike like it before. We organised the bike’s unveiling in Milan, with Mike Bongiorno. There were journalists, mayors, huge crowds. Gianni Brera wrote: ‘Ernesto Colnago, the Cellini of the bicycle.’ And he told my whole story.

What was the reaction?

Everyone criticised the carbon fibre bike. The International Cycling Union, under the influence of the big players in the sport – the Americans, Japanese, and Chinese, who were staging races in large numbers – said I needed to be stopped because I was too far ahead. They were producing bikes a year in advance to sell them.

I worked with Giorgio Squinzi, owner of Mapei. We went to Paris–Roubaix. I brought the steel bikes and also the carbon fibre ones, with a straight fork.

We tested them with Saronni and Savoldelli on descents and at the Politecnico. They didn’t break. So I brought them there.

Unfortunately, I was at home because I wasn’t feeling well. So I sent my brother, along with all the technicians and engineers, to oversee things. They were terrified the bikes would break apart.

They even told Giorgio Squinzi: ‘Listen, boss, if a frame breaks up north, on the cobbles, and our riders crash, it’ll be your fault.’ That evening, he called me: ‘Giorgio, what’s going on?’ ‘They want to mount a suspension fork on our bike.’ I explained: ‘How can we fit a suspension fork when it’s 12 centimetres longer?’ ‘Where does the rider go? Trust me!’ And indeed, he did trust me. I didn’t sleep a wink that night. Once the Hell of the North was behind us and the other stages came, a group of riders broke away – and we won the first of five Paris–Roubaix races.

That was the challenge I won against them all. And Colnago became Colnago, sought after worldwide!

What’s your relationship with Eddy Merckx like?

I’m still in touch with Merckx, not daily, but we speak about once a month.

Back in the Molteni days, I found a friend in Merckx. I built his first bike. We met one winter: he was taking the waters in Montecatini, and I was in Barberino di Mugello with my director, Albani. At Montecatini, he tried out the bike and was very pleased with it.

I won everything with Merckx. He would come here in the morning and wait until evening. Sometimes, he’d sleep over and take the bike the next day. I made over a hundred bikes for him. My speciality was custom frames.

In the Molteni days, with Merckx winning the Tour de France, he said to me: ‘Ernesto, I want to go for the Hour Record.’ We didn’t have the technology we do today to make the bike lighter. So I did what I could: drilled out the handlebars and used lightweight tyres and titanium spokes, all things that cost money. No one in Italy could make me a titanium stem. I had it made in America: two titanium stems to fit onto Merckx’s bike, which ended up weighing just over 5.5 kilos!

We went to Mexico City. King Baudouin was there with his wife and children, an unforgettable occasion. Merckx arrived with the bike on his shoulder. Belgian and French colleagues standing next to me were asking how I’d made it, but I couldn’t reply: I was too focused on how Merckx was riding, terrified he’d get a puncture. And on 25 October 1972, he broke the Hour Record. When we won, I collapsed.

Merckx has always been grateful to me. Every year on 25 October, if I don’t call him, he calls me. The last time, he rang to wish me a happy birthday. And on 25 October, I rang him while he was in Paris for the Tour de France presentation.

‘Ernesto, I’m sorry I didn’t call but today is a special day for us! Sending you a big hug – you know that.’

There’s only one Merckx but Pogačar is following in his footsteps! I had the honour, together with Saronni, of launching Pogačar’s career and winning his first two Tours de France. Pogačar is like a brother to me. He’s a hero.

How many victories have the ‘great Colnago’ collected?

I’ve won 16 Olympic Games, though back then, professionals didn’t race in the Olympics. It was the amateurs, and the strongest were from the East. So I gave bikes to Russia, Ukraine and Poland for publicity. That was the ‘small’ Colnago.

So what did I do? At the Paris trade fair, manufacturers would come to me saying they needed to make, say, 80 bikes. I would reply: if you want to be involved, you have to give me free saddles, free handlebars and free wheels. And we won every Olympics.

That’s how I made a name for myself worldwide, by winning the Giro d’Italia, the Tour de France, Milan–Sanremo… all the great races. I’ve won over 700!

And then?

I found a team called Alfa Lum from San Marino. They told me they wanted to sponsor for three years. They sourced drawn aluminium tubing from the East because they made aluminium window frames.

And that’s how Alfa Lum–Colnago came into being. All the riders came through that team and step by step, I became who I am today.

A memory that’s especially dear to you?

It was our 50th wedding anniversary. My wife and I had been together since we were 14. She was the only woman in my life.

One day, she said to me: ‘Why don’t you make a bike for me?’ I looked at her and said: ‘It’s our 50th wedding anniversary, how should I make it?’ ‘Make it with butterflies.’ ‘With butterflies?’ ‘Yes, because 50 years have flown by!’

So I made 50 bikes. One is here in the museum, and we sold the other 49 in a year at a special price.

How did the idea for this museum of your treasures come about?

The museum came about after we sold the company, first part of it, then the whole thing. And my grandson Alessandro said: ‘With all the original bikes we have, let’s build a museum.’

This place stands where the old factory once was. This is where we used to build frames and assemble the bikes.

Forty-nine people worked here. Everything took place here, right up to 2020. After that, we decided to tear it down, renovate it, and create this collection that tells the story of my whole life.

It was the year of Covid. I was feeling down; business had slowed. I was already supplying the Arab team from Dubai. They asked me, on the spot, if I wanted to sell the company. What to do? Seeing the state of the world and what was to come… I seized the opportunity!

But I told them they had to keep racing, and they replied that they would continue for at least five or six years, always with Colnago bikes. And I must say, they’ve honoured that commitment.

Of course, we built this museum to represent me, to keep me going. I get up in the morning, take a short walk, and then come home. People come, the museum is free, and lots of foreigners visit. There are often guests passing through, and I’m happy because at least I still feel alive. Otherwise… it’s been eight years since my Vincenzina passed away. Everything went with her…

Is there a particularly special piece in the collection?

When I met Pope John Paul II in 1979, he said to me: ‘I’m sorry I can’t cycle to Rome.’

Cardinal Ruini was standing beside me and said: ‘Make him a sports bike and he’ll ride it at Castel Gandolfo.’

Two months later, I returned to visit him. He received me, my family, and two Polish riders who were racing with me and had won the world championships and he threw a celebration for us. It was a wonderful experience.

The most beautiful part was that he invited me the next morning, at five-thirty, along with ten other people, to receive Communion from him. To be confessed by him and to receive Communion from his hands, that was something immense.

And the saddest moment, do you know what it was? There was an agreement that, upon his death, the bicycle would be put up for auction. Indeed, it went up for auction. Someone drove up the bidding and took the bike.

One day, a woman from Bocconi University called me and said: ‘I’m the secretary of Ms… who would like to speak with you.’ When I was put through, I realised she was a cultured woman. She told me she would be coming by to have a book signed for her father, who was passionate about one-of-a-kind objects and had had the good fortune to acquire the Pope’s bicycle.

I started crying, genuinely. And she understood. Then she said, ‘I’ll persuade my father.’ He came to see me and showed me how much he had spent. I stood there, looking at the price. Was it really worth it? It wasn’t peanuts. But I said to myself: if one day I open a museum…

Your professional life has brought you many honours.

Yes, I’m a ‘Cavaliere del Lavoro’ (Knight of Labour), and an Ambassador for the Values of Cycling at the United Nations. But the only one that truly honoured me – that made me suffer before receiving it, and that I feared I might not deserve, because I was being awarded something I had never actually earned – was the Honorary Degree from the Politecnico.

But speaking to important figures, I was told: ‘Ernesto, I don’t even have one. Ferrari didn’t get a degree either. And you receive an honorary degree: I would be honoured not once but a hundred times to be you, standing in front of that audience! You should feel honoured for the rest of your life because there’s no one like you!’

I received over two hundred phone calls after the ceremony. I was shattered. But inside, I had a surge of adrenaline. It exhausted me, but it also rejuvenated me.

I want to thank the Rector, Ingener Sala, all the engineers, and everyone in the audience. It was truly something special. At my age, it will be the last, but it was the most beautiful honour I’ve ever received. It shows I must have deserved it.

Thank you so much to the Politecnico, you honoured me with something I never expected. I don’t have the words.