Research is an integral part of design, better still if on an international scale. This is the principle that guides Alessandro Biamonti, architect, professor and coordinator of the Laboratory for Innovation and Research on Interior Design (Lab.I.R.Int).

The subject becomes even more interesting when it touches upon sensitive and complex subjects. For several years, Professor Biamonti has been working on non-pharmacological therapies for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, which is why we asked him to talk to us about his work.

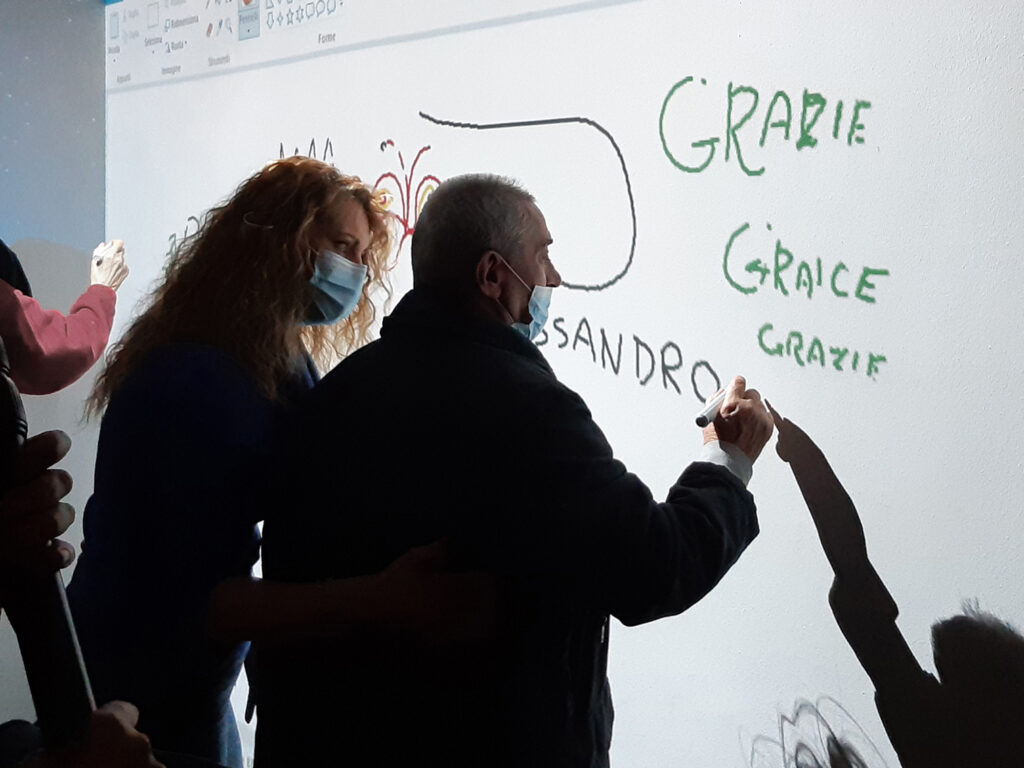

We met him during the filming of L’acqua non muore mai (Water Never Dies), a documentary directed by Barbara Roganti on the subject of Alzheimer’s focusing on first-hand accounts, stories and positive experiences. Part of the film was shot at Piazza Grace in the Figino district, Milan’s first Dementia Village.

Professor, what was the lightbulb moment that led you to research and create a project on this issue?

It was when I met Ivo Cilesi, a renowned therapist and innovator in this field. At the I and my colleagues were busy exploring interior design from an anthropological point of view, that is, the dimension related to senses and perception. We were investigating the mother-child relationship when Cilesi involved me in a completely different area: elderly people suffering from dementia.

The springboard for our meeting was a shared belief, namely that pharmacological therapies can be supported by what we call design. It should be remembered that Cilesi was introducing this type of approach in Italy, which at the time was not widespread but was of great interest to both of us.

As you suggest, design becomes a way to put the spotlight on patients and their wellbeing. Could you explain your method to us?

When I say “design”, I am referring to a wide range of practices: working on spaces but also devising devices and, often, services that operate around people with Alzheimer’s.

For some time, we have been trying to provide what we call Therapeutic Habitats, in which various elements are combined: aesthetics and ergonomics – the importance of which cannot be underestimated in the context of Alzheimer’s – and above all a primary focus on the quality of life of the individual. For our team, the habitats represent an important stage in a journey that began with interior design. At a certain point, the strictly physical dimension gave way to intangible elements, or ‘soft qualities’ linked to the sphere of perception and senses. We found it very useful to borrow the concept of habitat from biology, where this term indicates a set of conditions such as humidity, temperature, colours, sounds etc, rather than a spatial unit.

Discussions with social and healthcare professionals revealed the therapeutic relevance of such contextual aspects, starting with the observation that each of us is comfortable in some places and uncomfortable in others; that is to say, environmental conditions can induce a feeling of wellbeing or, on the contrary, provoke anxiety, irritation or sadness. These mechanisms are partly cultural or experience-related and partly anthropological, which, in the case of elderly people with Alzheimer’s, can have a crucial impact on their response to treatment.

A ‘habitat’ is also dynamic, sensitive to external inputs, often unpredictable and thus difficult to imagine as a project result. What role does the design element play?

It creates possibilities. It is an area that we have been working on for years now, in research and in educational workshops, alongside our students. Our projects are never completely finished, but rather they become a tool in the hands of someone else (therapists, in our case) and maintain a degree of adaptability and tolerance to unforeseen changes, given that every user reacts differently. One-size-fits-all solutions do not work in this context.

Could you give us some examples?

A classic case is doll therapy. This approach is subject to some debate: the patient is given a human-like doll, which usually has an extraordinary calming effect but is not universally effective. Ivo Cilesi pointed out to me that, in the case of patients having suffered trauma such as the loss of a child, the therapy can also cause discontent and frustration.

Our habitats try to mitigate these risks by focusing on greater flexibility through the development of a set of stimuli that can be configured for multiple virtual environments (a train cabin, a forest, or others), depending on the patient’s sensitivities.

Why do these habitats increase the effectiveness of non-pharmacological therapies?

Because they focus on action as a means to reduce or eliminate the administration of drugs, and the habitats usually allow the patient to relax without resorting to sedatives. Like, for instance, train therapy and the special compartment we designed, which simulates a journey with its various features (the landscape passing by, the conversation, etc.). It is an experience common to virtually everyone, which is generally relaxing and has a slightly hypnotic effect.

How important is the dialogue with therapists in your work?

It is key, since the initial idea usually comes from them. Working everyday with patients and their needs, therapists have insights that are often pivotal, but need support to translate them into appropriate solutions and responses, which is where we step in, as designers, architects and technicians. It is a team effort based above all on listening to one another. This type of cooperation works very well and provides valid support to the therapy, improving its effectiveness.

So, is it about turning their ideas into reality?

Not only that: in some cases, our task is simply to develop them; while in others, we introduce new elements, such as technologies that are little known or unknown to clinical staff. So, we designers also bring our own vision, sometimes in disagreement with the therapists.

For example, the proposal to make tests in simulated environments prompted great concern, since it was believed that the virtual-digital dimension would not be well received by the patients. This view was then disproved by the facts, and it immediately became clear that the elderly patients involved were more than active in their participation.

So, we proposed innovations that in the end were much appreciated, to the extent that we now have two ongoing projects based on virtual environments. In general, disagreements are not a bad thing insofar as they help us better understanding and improving action.

As designers, do you have direct interactions with Alzheimer’s patients?

Our contact with them always occurs in the presence of therapists and, over the last two years, they have been reduced to a minimum given the pandemic-related restrictions applied at day centres. In any case, yes, interaction does occur between designer and patient and indeed, it is fundamental for testing the effectiveness of the solutions that we come up with.

We should not think of design and research as two separate elements, especially in this field, where, besides envisaging unusual reactions by the patients, we also have to observe and analyse them, in order to create a sample case that will then guide the project in the right direction.

What can people with Alzheimer’s teach designers?

Above all, they (and their therapists) teach us the importance of keeping our mind as open as possible, as a prerequisite for the success of a project. The world of Alzheimer’s is made of people with characteristics that are out of the ordinary or, better, ‘extra-ordinary’, which force the designer to think beyond the ‘normal’ or ‘standard’ parameters, whose limitations are moreover acknowledged even in conventional design fields. This makes the work more demanding but definitely more compelling, by bringing into play the very culture of design.

Another observation that I would like to make is that, by interacting with these people and experiencing their living spaces, we realise that Alzheimer’s is a condition one can live with. I believe this is an important message for anybody, not just designers.

The output from your research includes a number of degree theses. How do you assess the contribution of your youngest collaborators who are far removed (in terms of age and experience) from dementia-related issues?

We tend to think that young people are not sensitive to the problem, but that is not the case. When we did the first workshop about ten years ago, knowing that I was going to meet students in their early twenties, I thought: they are young, they enrolled on this course to design nightclubs and shops, so who knows what they will throw at me when I tell them what we are working on! But I was totally wrong. In the space of three days, they had delved into the subject, understanding its essential elements, and proved they could respond with reasoned and mature ideas.

I am pleased to say that I was never disappointed so far, and that the course is still going on. This year we have 60 participants: 10 more than the previous class. Students often come to ask me whether there are opportunities in the social sector and how to work as a designer in this particular field once they graduate.

Where does this interest come from?

There are at least two elements to consider.

the first is that, due to the increase in life expectancy and certain social factors, dementia is becoming more common in households. Therefore, a twenty-year-old nowadays tends to be more familiar with this type of condition, when compared to a few decades ago. It is enough to consider that more than half of my class have a relative or a close person affected by Alzheimer’s.

The second factor is generational, I shall say: they are good kids, who care about others and apply themselves seriously to what they do, and not layabouts who live on the internet, as some people think. Even our clinical partners are often impressed by their work, like the videos I ask them to create at the beginning of the course to ‘break the ice’.

Lastly, we know that Alzheimer’s and dementia are still subject to social stigma. How might a communication product help improve the public’s understanding of these people and their sensitivities?

By informing and revealing more than just the negative side of the disease. Although we must remember that it is a syndrome, with all its own criticalities, I believe it is also important to talk about the subject in its fullness.

There is in fact another side to the story: that the lives of these people are not ‘lost’ and, on the contrary, they can retain a quality of life that I have no hesitation in describing as good. This is possible as long as the rest of us manage to overcome the rigidly rational perspective and embrace, as far as possible, their points of view on things, which is often surprising.

Could you give us an example?

The title of the documentary that is being filmed: “Water never dies”. This was a phrase uttered by a patient with Alzheimer’s, which we would never think to say. Because of Alzheimer’s, these people develop a detached perception of reality and express an eccentric view of things that, in some ways, is similar to that of artists. After all, even Picasso broke down perspective and was judged to be mad by many; yet his art revolutionised the twentieth century.