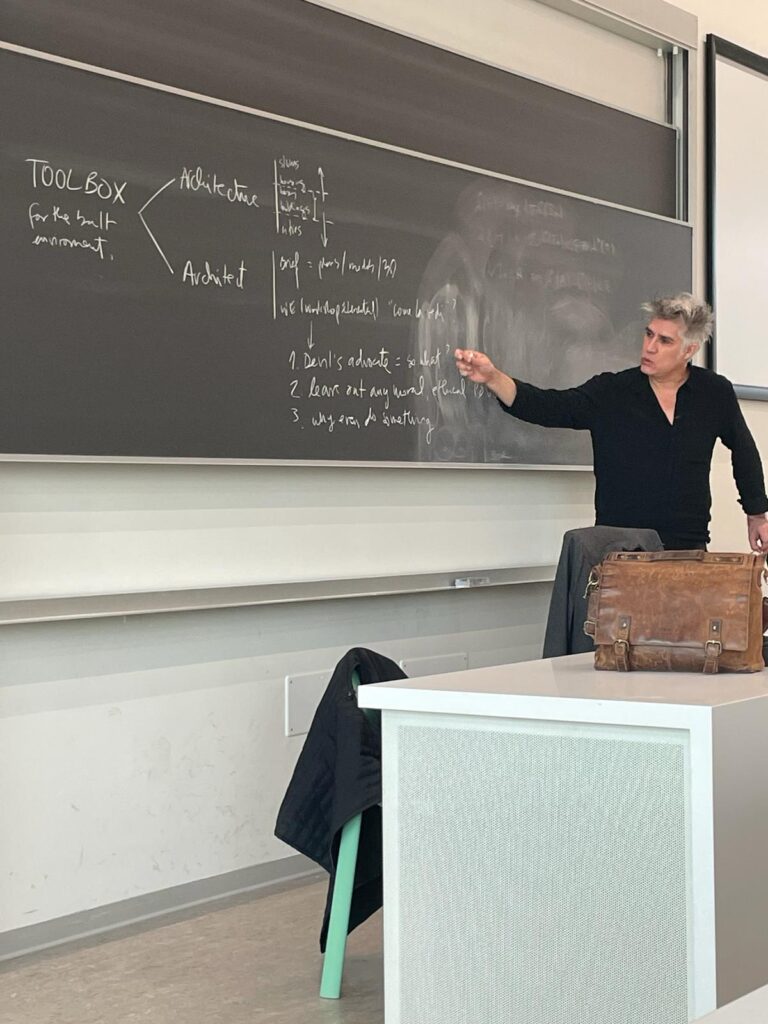

We had the opportunity to meet Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, winner of the 2016 Pritzker Prize, during his workshop with architecture students. He talked about how they are discussing the housing problem in Milan, how inequality can be tackled by giving everyone equal opportunities from the start, and then focusing on incremental improvements. To young people, he advised: “Be nerdy, but at the same time, irreverent.”

After graduating in architecture from the Universidad Católica de Chile in 1992, he became a professor at Harvard University and founded Elemental in 2001 with partners Gonzalo Arteaga, Juan Cerda, Victor Oddó and Diego Torres. In 2010, he was appointed Honorary International Fellow of the Royal Institute of Architects. He has been a member of the Council of the Cities Programme at the London School of Economics since 2011. His work has received several awards, including the Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale (2008) and the Gothenburg Prize for Sustainability (2017). In 2016, he received the Pritzker Architecture Prize and served as curator of the 15th Venice Biennale. Since 2020 he has been President of the Jury of the Pritzker Prize. At the conclusion of the workshop, Aravena gave a lecture entitled Elemental: the Current Toolbox.

We’ve caught you during a break in the workshop. What are you all working on?

We began with the idea of expanding my toolbox and adding new tools. Drawing on the education I’ve received and what I’ve observed to be necessary for addressing the challenges of the built environment. Having been trained primarily in designing houses and buildings, I needed to understand the basic fundamentals of constructing social housing in emergency situations, such as in slums. To view the buildings of the city as spaces that determine how people will live together.

At the same time, I was trained to receive a brief from a client and to apply what I had learned by implementing design strategies. But what happens when there is no brief? What do you do when the question is unclear, even to the client?

So, what we are doing here in the workshop is, first of all, understanding the forces at play and identifying the challenge. Additionally, it’s important to understand if there is a problem. The assumption is that Milan is so expensive that students cannot afford to live here, so it makes no sense to study in Milan if you can’t afford to live where you study. But not only for students. Even workers can’t stay due to the high cost of living. A ballerina at La Scala can’t afford her accommodation. So what now? Even if wealthy people or tourists can come here, but a ballerina can’t afford it, then something is wrong. These are facts, but I wanted to try to play devil’s advocate. So I talked to the students. Asked the “So what?” question. Is there a risk? Is there a problem? Because this phenomenon could eventually lead to Milan losing its critical mass, as the ability to attract ideas, people, knowledge and resources is now limited to a few. It’s no longer competitive, and this has occurred many times throughout history. But I really want to understand if this is a problem. Many other cities, such as Paris, London and New York, face the same issues. Perhaps this is Milan’s finest hour; never before has it attracted so many tourists.

So I really want to leave out any romanticism, any bias, any prejudices. Because at the end of the day, if, after all this analysis and listening to so many voices, not only those who complain about a problem but also those who see it as an opportunity, there is a need to take action, then that will be very compelling. It’s not as if it’s something you do just because you’re expected to do it for political correctness.

This is the idea of expanding the toolbox to include strategies, areas of design and architectural operations that are not necessarily what society expects from an architect.

We’re at a university and, reflecting on your career, you’ve designed many school buildings. How did you design them, thinking about who would inhabit them?

Yes, this is perhaps what is typically expected of an architect who designs buildings. This should be the starting point, but that’s not always the case.

Perhaps the main problem with architecture is that too often we architects focus on issues that only interest other architects, so in the end are you postmodernist, are you modernist, are you minimalist, or are you deconstructivist? And society doesn’t care about any of this.

Instead, what if the starting point is not the contribution to architecture but the contribution to society? Understanding the issues that concern citizens and engaging in a discussion not solely about architecture but with an understanding of architecture. And this is perhaps the challenge of our profession. I don’t wake up one morning with an overwhelming desire to design a building; rather, it begins with someone needing a building. The process starts from external needs, not from within yourself.

Once there is a need, a desire or a lack of something, the first step is to focus your work on meeting that need. This by definition, will be a need, a life, a university, a work space. How do you pass knowledge down from one generation to the next? How do you create knowledge? You design a structure that fosters the conditions for this to happen in the best possible way.

From the start, you focused on that need or desire. What was less clear at the time was that, beyond the more conventional aspects, that need also exists. Normally, we architects don’t have the tools to reach places where there is no expectation of architecture. This is where the need to expand our toolbox emerged.

You’ve even been referred to as ‘the architect of the poor’. Could you explain how you developed these designs for people with fewer economic resources, such as the modular houses that allow for the second part to be built later?

The label ‘architect of the poor’ has become a bit of a leitmotif. What’s important to recognise is that cities often reflect inequalities in ways that are not only tangible but also part of daily life, and sometimes quite harshly. At the same time, they can serve as a shortcut to equality, I should say equity rather than equality. They are two different things. Because when we talk about equality, the aim is for everyone to be the same, whereas when we talk about equity, the focus is on ensuring that everyone starts from a common base and has access to the same opportunities. Then some will advance to a certain point, while others may progress a bit further. I’m not concerned with the end point; what matters is that the starting point is levelled. The city provides the opportunity to address the differences in starting points, as it can enhance the quality of life in a relatively short time.

If a person lives in social housing that is far from their workplace, with limited public transport, few services and inadequate public spaces, this situation must be improved without negatively impacting wages. The city can play a key role in facilitating these improvements.

This means that housing must be constructed in locations that offer opportunities, services, infrastructure, public spaces and efficient public transport. So you can address this starting point inequality and enhance quality of life without impacting income.

From this perspective, I was interested in using architecture for its ability to transform the spaces where we live together as a shortcut to equity. Moreover, many more people live in these areas, so if you have to choose where the impact occurs, don’t select the elite. Instead, focus on places where even the tiniest improvement can make a significant difference.

How do you manage to combine a scarcity of resources with innovation while ensuring quality housing?

This obliges you to respond in a way that is relevant to the needs, eliminating anything superfluous, anything arbitrary. From this perspective, it’s not only a moral or ethical question; it’s also a matter of professional precision.

If you want to use cities as a shortcut to equity, if you want to impact as many people as possible, if you want to focus on areas with fewer resources, then it’s more likely that those you serve will be the poor.

This led to the idea of allowing for the construction of a part at a later stage.

Yes, precisely when you lack the money or time to do everything at once, the solution to scarcity is incrementality. An open system that can grow over time. Incrementality was one of the strategies we identified, so that when you need to hand over social housing that is insufficient, those families are not condemned to remain at that initial standard but can improve it over time.

This can occur either through public resources that become available later or through contributions from their own families. The goal is to create an open system, not a closed one. From the standard minimum starting point to the maximum, there is a gap that can be filled with various resources, sometimes private, sometimes public, and sometimes from the families themselves. The goal is to leave a space in which the starting point, the minimum, is not equal to the end point.

I wanted to understand how you begin your work; I saw some very nice sketches. How does the design of a building begin? What studies do you conduct, and how important is participation in the process?

I believe it’s crucial not to want everything too early. If I know in advance what I want to do, then the client, the job becomes merely an excuse to add something to my creative portfolio. On the other hand, if it’s not clear at the beginning what you need to do, you should be able to postpone your intentions until you fully understand the question at hand.

Our approach is to first design the question, and only then design the answer. To design the question, we ultimately shape the places where people live.

What are the forces at play that will influence that final form? When you start to understand and identify those forces – economic, political, legal, social, environmental and aesthetic – then you can attempt to take that leap into the void of creation and design. This process is synthetic, as it must synthesise those forces that sometimes push in opposite directions or are contradictory.

The question must also stand alongside its contradictions, and it will be the role of design to resolve that contradiction or complexity. The more complex the question, the greater the need for synthesis. If there is any power in architecture, it lies in the power of design synthesis. A design organises information as a proposal, not as a report. It’s a leap into the void of “What if?”

What do you think Milan needs most right now?

I’m conducting this workshop to find out. This week, we invited representatives from real estate, banks, activists and politicians to discuss this phenomenon in Milan. Everyone who has something to contribute, without any prejudice, in an attempt to understand their perspective. Once we have identified the forces at play, we may be able to understand the question rather than immediately attempting to build social housing, which could be one potential solution.

It may be that the solution is to do nothing, in the sense that relocating the university to an area where housing costs are more affordable could be an option. Alternatively, the solution might lie in mobility or perhaps in financial policy. Sometimes the solution does not lie in architecture. It’s also important to recognise that once you’ve identified the question, it may not be the role of architecture to provide the answer. Sometimes architecture is necessary, but not always. This is an exercise we regularly perform at Elemental.

Elemental is your studio in Santiago. How many people are there, and how is the team organised?

There are 16 of us. Our studio aims to remain as small as possible, but we have partnerships with several local studios to work on projects elsewhere. In Portugal for example, our partner is João Luís Carrilho da Graça, and in Mexico we have Ibarra.

We work closely as a team, fostering great harmony and camaraderie, which would be challenging in a much larger studio with many people. For us, freedom is particularly important. The smaller you are, the freer you can be, so we aim to be large enough to handle complex projects, but not so large that we become burdened by excessive team costs.

This is important when the demand is for intellectual independence and professional freedom. Sometimes, it’s necessary to remain very detached from the interests at stake to provide an effective response. As we’re often called to enter conflict zones, it’s essential to maintain that independence and freedom. Otherwise, you get lost.

And one last question: what advice would you give to a student who is about to start studying architecture?

I’d advise them to be as nerdy as possible, to devour as much information as they can. If someone wants to enter the field now, they are already late, as architecture has a history spanning thousands of years. I’m the one who has to go there and devour all that knowledge.

At the same time, they have to be iconoclastic and irreverent. It’s not the case that understanding everything there is to learn means you must simply obey. You need to use that knowledge to challenge the status quo, question assumptions, provoke issues and go beyond business as usual. As I think it was Lautréamont who used to say, “You have to devour a forest to produce a toothpick”, which captures the essence of this idea.