When we think of scientific research at Politecnico, the first image that comes to mind is that of experimental laboratories. Today we will explore a different approach with Roberto Dulio, Rector’s Delegate for the Archive, library and museum system, who opened the doors of his world to us.

Roberto Dulio, an architectural historian, offered us a passionate and profound perspective on the meaning of this type of research. With huge experience in the field, which includes curating exhibitions, academic publications and a long career in the field of architectural historiography, Dulio tells us not only about the path that led him to investigate the events of the twentieth century, but also about the importance of rediscovering lesser-known figures, such as the architect Giuseppe Martinenghi or the photographer Ghitta Carell. Through his story, it clearly emerges how curiosity and determination are the driving forces of historical research, capable of revealing new interpretations and stories that, otherwise, would remain in the shadows.

In a university like the Politecnico di Milano, research in the history of architecture is not always in the spotlight. What are its peculiarities?

The history of architecture is a subject that involves research that is very different from the research we are used to coming across, because it is research on the past. This does not mean that it is “dead” research, on the contrary, every time we investigate the past it is because contemporaneity poses questions about it. The history of architecture is not something static or untouchable: it is always in flux.

Research on the history of architecture does not involve experiments, but is mainly based on the analysis of sources, such as archives. These archives are often produced by us historians or by institutions such as the Politecnico, but we also draw on external archives, both public and private.

The work of the architectural historian is to, starting from the sources, be able to give interpretative hypotheses to certain phenomena.

What is the role of the historian today?

A phenomenon studied today could be reinterpreted tomorrow in the light of new perspectives. It is therefore clear that the story is potentially endless: it is not just a matter of archiving data in a filing cabinet, but of discussing its contents, always keeping in mind the scientific method. The main production of our work is publications, such as articles, monographs etc.

In the last period I have noticed that there is a great interest of the public, outside the Politecnico, in the history of the buildings and the city. This growing demand for narratives about cities made me and a colleague of mine reflect on an idea: to create a startup that deals with historical narratives related to architecture and cities. In this context, the role of historians would be to guarantee disciplined and scientifically based knowledge, because often those who are involved in telling these stories do not have a solid background behind them.

Let’s get to the heart of your activity. What is your field of research, more specifically?

Within the Politecnico we are many historians of art and architecture, and we all study different eras. I am a contemporary: I mainly deal with the twentieth century, in particular the period between the two wars and the immediate post-war period, up to the fifties and sixties.

An architectural historian to whom I am very attached, Claudia Conforti, to the question: “What is the history of architecture for?” she always answered: “Nothing, but it is necessary”.

It is necessary to understand both what were the steps by which a certain type of architecture was arrived at, and to be able to understand the historiographical stratifications of the place on which one is going to operate, which is an absolutely essential element. This type of approach, actually, is a peculiarity of Italian architectural culture; In many other countries, in the education of architects, history is present in a minimal way.

How much is the history of architecture intertwined with the history of contemporary culture?

Talking about architecture means talking about a very broad cultural climate. For example, when I study interwar architecture, it is impossible to separate it from political history. However, it is essential to underline that not everything produced in those years is linked exclusively to fascist culture, and that therefore it must be condemned. It is a much more complex phenomenon that historiography teaches us to examine at different levels. Studying the history of those years means examining daily life, the collective imagination, the risks of the period, as well as the artistic debate and the relationship between architects and artists.

Give us an example

In my research I have always moved a lot on the relationship between artists and architects during the thirties.

For example, I delved into the figure of Ghitta Carell, a photographer who was very active in the thirties. It all started by chance, while I was working on an architect at the time. I couldn’t find much information about him, until one day, in an archive, I came across a photograph taken by her. This opened up a number of unexpected connections, because I found more photos of her of architects and influential people, including Maria José and Mussolini. At that point this photographer began to intrigue me.

However, what captures my interest is her personal story: Ghitta Carell was a Hungarian Jewish photographer, naturalized Italian, who after 1938, due to racial laws, was no longer able to practice her profession. Despite this, photos of Mussolini continued to be used with his name clearly visible. Subsequently, from the Central State Archives in Rome, I discovered that there was a correspondence between Ghitta Carell and the Duce’s Secretariat. From there I found out that the photographer had tried a lawsuit against Mondadori, because they were using her photographs of Mussolini without paying her royalties.

Thanks to this documentation I am able to trace the filing number of the case, which leads me to an archive of the court of Rome, outside the city and difficult to reach. With a lot of luck, I manage to track down the cause, obtaining a lot of unpublished information about her. In the meantime, I was working on themes that were more disciplinarily related to my attitude, but my interest pushes me to continue buying portraits of Ghitta Carell at auctions. By pure chance, I met an enlightened gallery owner, Massimo Minini, also passionate about photography, who put me in touch with a publishing house, Johan & Levi. So, this research turned into an editorial project: a book on Ghitta Carell.

This type of project, compared to my academic career, may seem collateral, of course, but it is only up to a certain point. In the end, this work brought together many elements related to expressive imagery and a historical context that does not only concern architecture, but an entire cultural climate of that era.

Where does your interest in historiographical research come from?

Personally speaking, I think it all stems from curiosity. There is always a question that emerges, something that we do not know and that pushes us to want to deepen. In historical research, in particular, we often come across aspects of the past that surprise us or details that lead us to reconsider ideas that we thought were established. When a building intrigues me, I want to understand who designed it, why it looks like that, what the story behind the construction is.

For example, a colleague, photographer Sosthen Hennekam, and I are focusing, together with Davide Colombo and an architect who graduated with me, Andrea Coccoli, on a twentieth-century Milanese architect, Giuseppe Martinenghi. It is not a well-known name, but it played a fundamental role in the construction of Milan between 1930 and 1940. In ten years, he built over 100 buildings, a surprising amount for the time. This makes us understand that the city is mostly made up of secluded and silent characters like Martinenghi; there are many designer buildings in Milan, and we all know them, but they are a negligible percentage compared to the vastness of the city. In addition, the buildings built by architects such as Martinenghi often have a high quality caliber and are also very significant because they represent the synthesis of expressive characteristics of the time.

How do you deal with the study of a “minor” character?

First of all, you have to understand his cultural background. In Martinenghi’s case, we are talking about a period in which architecture could follow two main paths: a technical one relating to the area of engineering, and an artistic one, which required a diploma in architectural drawing. Both of these paths allowed to practice the profession of architect. Once his education has been reconstructed, the next step is to identify the buildings it has built. In this case, the historical archive of the Municipality of Milan at the Citadel of Archives comes into play: by providing the civic address of a building, it is possible to access the documentation from which it is possible to trace who participated in the construction – from the company to the architect.

At this point, the eye of the historian who goes around Milan and tries to understand which buildings may belong to him also intervenes, with consequent verification in the archives. In addition to official documents, it is also necessary to refer to the literature of the time, such as the numerous magazines that published articles on buildings in the thirties. Obviously, literature does not mean limiting oneself to libraries, it also means searching in flea markets, private collections or finding information through chance encounters.

In this regard, here is a surprising discovery, as unexpected as it is. One day an antiquarian bookseller, with whom I had been dealing for some time, sold me a book by Martinenghi. Once he perceived my interest, he revealed to me that he had the architect’s archive. Amazed by the news, I immediately notified my research group, as until then we had never been able to find him. In the end, it wasn’t the entire archive, but six boxes full of material, which helped us understand a lot more about him. The bookseller, who had promised us to have more material, out of the blue, however, disappears. This makes us understand how every search has its challenges and unpredictability.

What does it mean to work on figures like Martinenghi?

Working on Martinenghi does not only mean cataloguing his buildings. It means illuminating a broader phenomenon: the construction of the city. Milan, like many other cities, is not only made up of architecture signed by the big names that everyone knows, such as Giovanni Muzio or Gio’ Ponti. Sure; these have historical importance, but represent a minimal percentage of the urban fabric. Much of the city was built by lesser-known architects, such as Martinenghi.

Together with the professor of the Politecnico with whom I graduated a long time ago, Augusto Rossari, I believe even before becoming a researcher, we conducted a quantitative study on the designer buildings of Milan. We compared the censuses of spaces built each decade with those signed by the big names and found that only 1-2% of Milan’s buildings were designed by famous architects. The rest is the work of figures like Martinenghi. Understanding this means reconsidering the role of these minor architects and their influence on the city.

Can history emerge even from seemingly insignificant details?

Certainly. Take, for example, this mug by Piero Fornasetti. If a historian is curious, a world emerges. In fact, if you investigate deeply, this mug can tell the story of an artist like him, who revolutionized twentieth-century design. Fornasetti, who initially wanted to be a painter, worked a lot with architects. For example, he collaborated with Gio’ Ponti decorating furniture disguised as buildings or interiors of large ships with the technique of decoupage even before it existed as such. His approach has changed the way we conceive of design, and all this can be discovered starting from a mug.

Historical research is also this: it starts from a detail and, if conducted with the right curiosity, manages to bring out a universe.

Returning to your role as delegate, can you explain how an exhibition is actually realized?

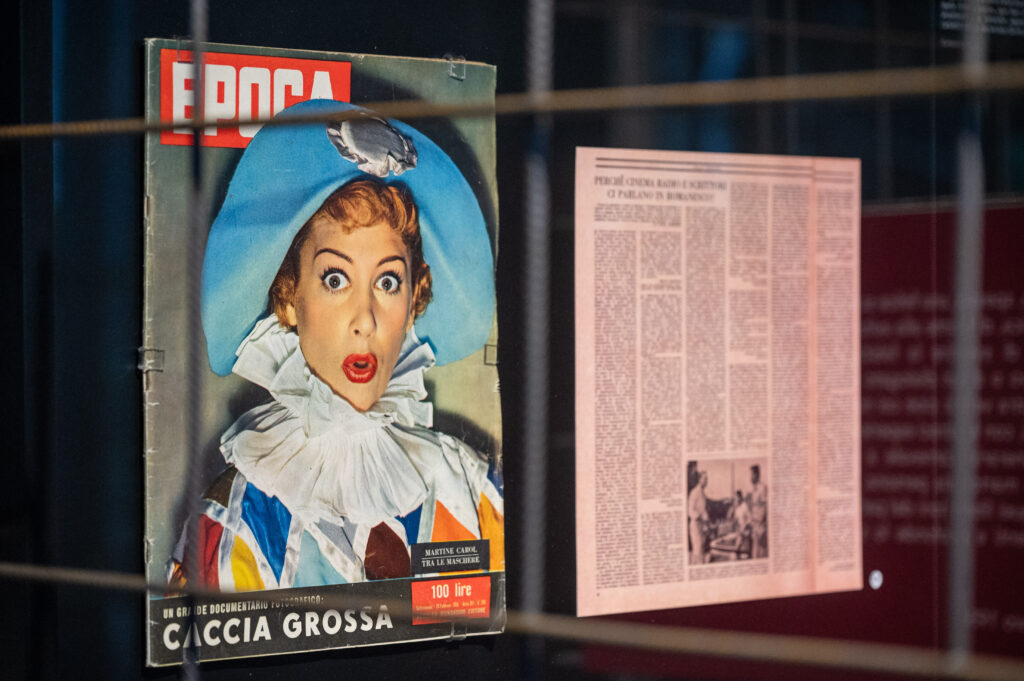

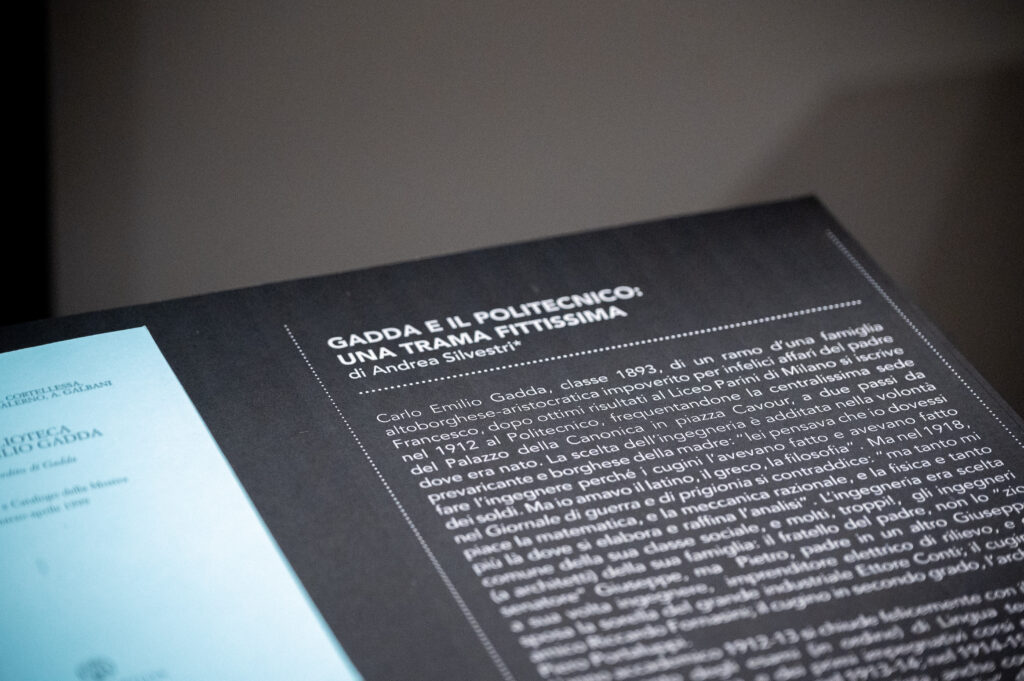

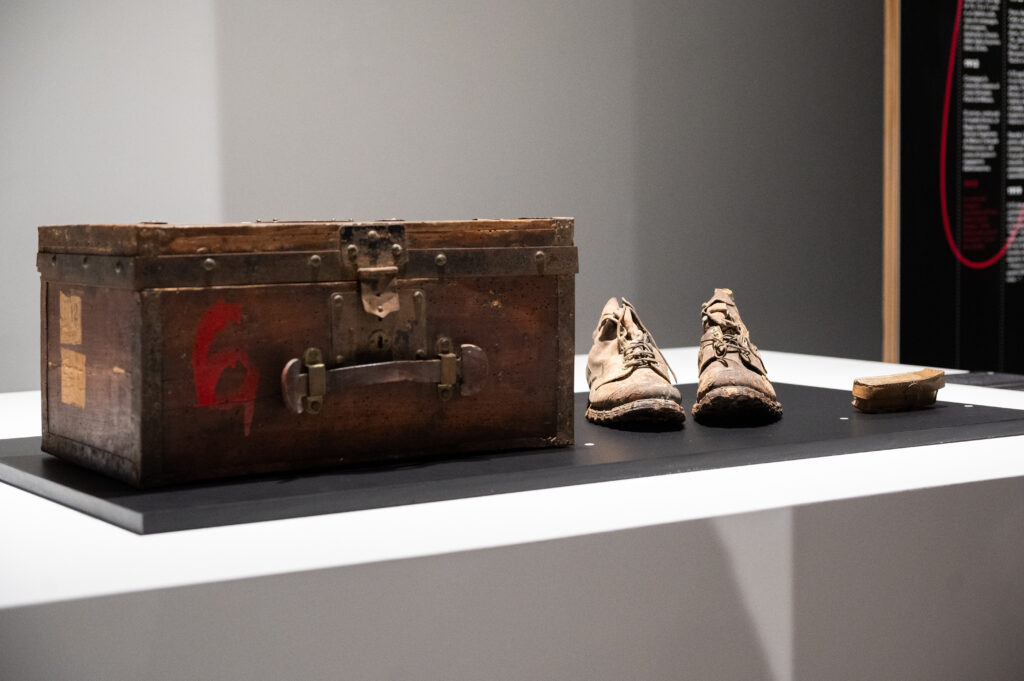

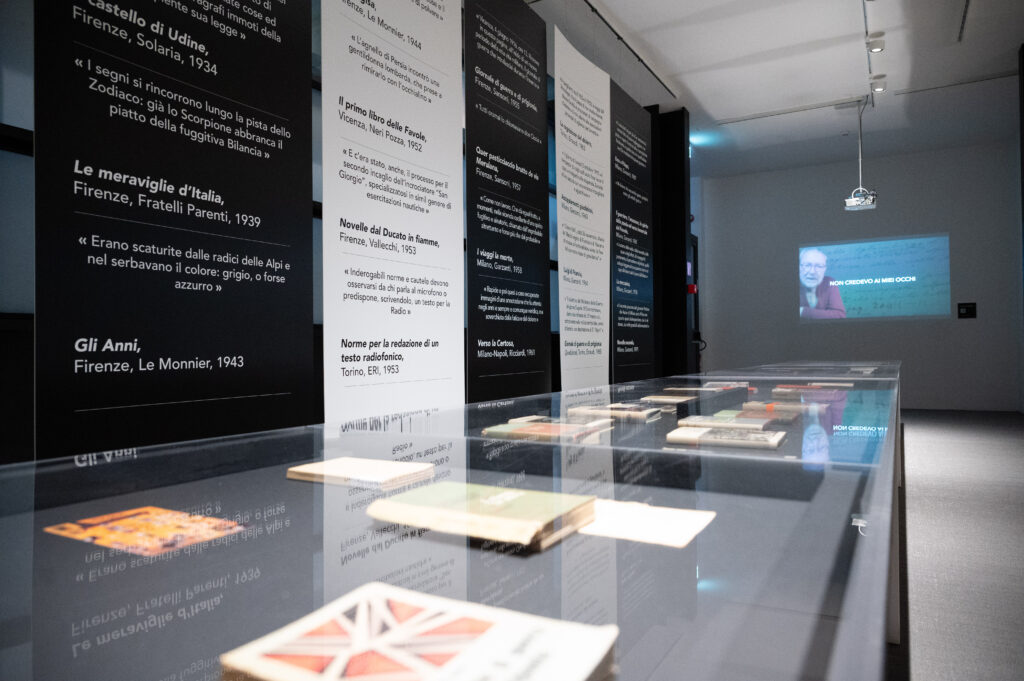

Let’s take as an example the case of the exhibition Cantieri di Gadda. Il groviglio della totalità (The tangle of totality), recently concluded here at the Politecnico, carried out in collaboration with the Centro Studi Gadda at the University of Pavia.

Setting up the exhibition was anything but easy, because it had to be the right compromise between the philological needs of Gadda’s scholars – Claudio Vela, Paola Italia, Mariarosa Bricchi, Giorgio Pinotti – and other elements that could tell a complete story. Once we had gathered all the material, we put it on a table and began to deal with our budget, trying to figure out how many of those materials we could actually afford. Obviously, before choosing the materials that would populate the space, we decided what was the story we wanted to tell and how – together with Massimo Ferrari and Claudia Tinazzi – we would make it intelligible.

The materials in the exhibition came from about twenty different institutions, and each loan requires authorizations from the Superintendencies, which must guarantee the suitable conditions for the conservation of the objects and texts. So, for each institution this step had to be made and the pieces had to be secured.

From this moment on, the fun began [laughs]. Each institution arrived with a companion. Some came with the materials and made sure they could only be touched by themselves to be placed in the display case. This is to make it clear how meticulous the process is, even for what at first glance might seem like a “small” exhibition.

But it also applies to major exhibitions…

In fact. Let’s take another major exhibition like the one on the Thirties made by the Prada Foundation, Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. We are talking about a colossal exhibition, with very precious objects. The budget was huge, and the organization also took years. The title, inspired by the famous Futurist poem, was the result of a diplomatic choice. This is to make it clear that often those who organize an exhibition do not always have full freedom of choice. You always have to find the right balance between the “scientific” nature of the exhibition, the artist’s desires and the will of the financier.

What happens if some work is stolen or damaged?

The works are always insured, with a “nail-to-nail” policy. This means that from the moment the work is detached from its original place until its return, whatever happens to it, it is covered by insurance. In the event of theft or damage, the owners, whether public or private, are compensated. For investigations, there is also the Cultural Heritage Protection Unit of the Carabinieri, which is extraordinarily efficient. In addition, there is a publicly accessible database with all stolen works registered. But I would like to reassure all collectors and lenders: today (almost) no one steals a work of art. A work of art that has a commercial and artistic value is documented and no one would buy it without guarantees of provenance.

An analysis of this first year as Rector’s Delegate to the Archive, library and museum System?

Let’s say it’s a fairly complicated role. First of all, it is a delegation that brings together the exhibitions, the archives, the libraries that are linked, but they are also very different things. All these sectors are the responsibility of the Campus Life Area, directed by Chiara Pesenti, with whom an excellent relationship was immediately established.

On the libraries it was more a simple job to fine-tune, thanks also to the extreme skill of the managers: Carmen Cirulli and Piero Ruggeri. The same goes for the archives, where I am a supervisor, while the very competent person in charge is Anna Colella. In particular, from this point of view, the Politecnico di Milano has many archives, many of which we have collected: we really have a lot of material and much more will come in the future. There will therefore be an increasing need for spaces and structures that accommodate this material.

I am really very happy to have this delegation, because I have a function of responsibility in an area that I frequent, that I know and that I feel mine and this makes me extremely happy. My life is certainly more complicated, I have much less time, but I deal with things I’m passionate about.

What was the relationship with your predecessor, Federico Bucci?

We were very good friends; we had known each other for about thirty years because we were in the same department. I graduated in 1997, when he was already a graduate technician and at the time, almost no one considered us. He was about ten years older than me and worked a lot in the department. We started several projects together, in parallel: in the early 2000s, we reviewed for the magazines Domus, L’architettura cronache e storia and Casabella. It is curious how at the time no one was surprised by our simultaneous presence on three newspapers, which were also a bit in competition with each other. Evidently our area of interest was not considered strategic [laughs].

Subsequently, Federico won a competition and became an associate professor at the Politecnico di Milano. In the meantime, I continued to collaborate with Claudia Conforti, and together we worked on a book dedicated to Giovanni Michelucci. Subsequently, I also won a competition and became a researcher here at the Politecnico. Federico then became a full professor, and I became an associate professor. Many of the things I have done, I have created together with him, such as the exhibition on Aldo Andreani in Mantua and even before that a small book, a guide to contemporary architecture in Milan, now impossible to find. In all these years we have shared many experiences together, and being here is like continuing a path that I started together with Federico.