The inauguration event of MANTOVARCHITETTURA 2025 was held by the world-renowned architect and architectural theorist Daniel Libeskind.

Recognized as one of the leading figures of deconstructivism, he has masterfully combined memory, history, and innovation in iconic works such as the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the masterplan for the World Trade Center in New York. With a cosmopolitan education spanning Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom, he has taught at prestigious academic institutions. His architecture is marked by a strong ethical and symbolic commitment, often addressing themes of trauma, identity, and collective memory, expressed through a bold and deeply expressive formal language.

We met him the day before the opening at Palazzo Te in Mantua. After the visit to the magnificent Renaissance villa by Giulio Romano, we had an insightful conversation with him.

Good afternoon Mr. Libeskind and thank you for your time.

It’s a pleasure.

Tomorrow you’re inaugurating MANTOVARCHITETTURA with a conference of yours. Can you tell us something about the topics you are going to address?

Yes. A thing that I’ve always considered important, particularly today, is memory. And also, the theme of connection between memory, history and the contemporary world.

I’ve noticed in your work a persistence of the themes of memory, history, trauma and their intersections. I’d like to know if your vision about memory has changed along the years.

It’s a good question. First of all, I don’t consider memory an additional dimension to something else. I consider memory the foundation of architecture. It’s not an extra, it’s the ground of architecture.

And we see today that the memory is not enough.

How can memory be involved in these tough times of conflict?

Memory has to turn into action in face of today threats to culture in political ways.

We can see by the rise of a different world of domination, which is not all just a purely capitalist world, but a world of new ideas about control of the environment. It’s propaganda, it’s surveillance.

All these things show us that memory is even more important today than when I started. When I started, memory seemed to be very stable. But I think what we see today is the instability of memory, which requires a quite different approach, because without memory I think we would be doomed.

Not just condemned to repeat the same things, but to be lost altogether in terms of heritage, culture, identity.

So, in this way, memory is more important today than when I started.

Do you think that architecture can help in avoiding the errors of the past? Nowadays is it trying to do it or it just can’t?

Well, we know that architecture is the greatest structure. It’s the art of memory, because architecture really represents repository of memory, much more than internet or computers or the AI.

Architecture is even more important than it was before. I think today we are threatened with artificial memory, just like artificial intelligence.

And what does that mean for humanity? For human beings, to have an artificial array which is attached to a sort of non-existent being.

So, the problem is not just philosophical or political, it’s structural for architecture. How do we create in an era of increasing detachment from memory? An era when memory turns to virtual memory, which you can wipe away with a single move of the mouth.

You cannot do that to architecture. It’s so much difficult to get rid of architecture.

We’ve just seen in Giants’ Hall, here in Palazzo Te, the notion that in this building also there is a vision of destruction of architecture by the giants. Very appropriate for today’s thinking.

This might be a naïve question, but is there one of your projects you’re particularly attached to? Or your vision resonates in each one of your pieces of work?

I do hope the latter. The Jewish Museum Berlin was my first project, my beginning. It’s particularly important because I’d never done a building before, not even a small; and the beginning is important, because it puts you on a certain road.

This road has been very large, and I’ve been fortunate to work on many new projects with new ideas and new themes. I think I’m currently working in 15 different countries.

I don’t know if it’s true, but I read that in the 1980s, after four years, you decided to leave Milan because you considered Italy a beautiful country where it’s impossible to work as an architect. Has your opinion changed since then?

No, it’s not really true that I said so. I loved being in Italy, and Milan in those years, in the mid 80s, was a real hotbed of incredible talent, creativity.

But my leaving was actually an organic transition because I had won the competition for the Jewish Museum in Berlin while I was in Milan, so I had to move to Berlin.

And today, Milan bears your mark, with the CityLife tower. What’s the vision behind this project?

CityLife has been a project that took many years, but it’s really now a living part of the city.

It’s true, the building I conceived is like a hug towards the square. It is an attempt to give a unity to the three different towers, which are done by three different architects. We worked together with Zaha Hadid and Arata Isozaki to mimic each other’s geometries and create a composition that was harmonious.

And I think you succeeded in the result.

Yes, I’m very happy, because we had our own internal competition to do the masterplan. I think it was a fruitful collaboration so as to create something like a real place, not just buildings.

There was also the will to make it environmentally advanced. I really concentrated on sustainability and green space as opposed to more asphalt, to change the attitudes to 21st century living in in Milan. And yes, I think that’s part of CityLife vision.

What would you say to a student who wants to become an architect? And what has it brought to your life being an architect?

Being a student today is harder than it was before because there’s so much of the in-between space which is filled with. Technocratic instrumentality, including the virtuality with which architecture is being produced. You know, there are many offices that use only AI for generating design.

To me, to become an architect today, you should go back to the roots of architecture. You have to do something very radical, to break through the sort of zone of mist that obscures actual culture. In architecture it’s more difficult, because of many factors.

So, my suggestion would be: if you love architecture, you’ll have to follow your dream from the beginning of time. And that’s memory.

Do you feel you still have a lot to say to the world? Or something you haven’t said yet?

Well, yes, many things. I have new projects almost on every continent: South and North America, Asia, Europe.

I’m truly fortunate because architecture has an amazing future. Creativity has no bounds, and technology also is something immensely incredible, if one can use it in the right way. We are living in an incredibly interesting time and of course architecture is also changing with the social structures, culture, technology. And that’s exciting.

What can be the point in your career, the project, the moment gave you most pride in what you were doing, if you could choose one.

There are many moments, but they don’t depend on how big a project is.

I just finished a house. Maybe I have built only three houses in my life and I’m working on another. Not every project should represent everything you stand for. There should not be a minor project or a major project because everything is concentric to where you are.

I’m lucky because with every project I try to open some inroads to really different areas, different countries, different cultures, different requirements.

Of course, you don’t choose the project: it’s the project that chooses you.

It’s a really interesting vision.

And it’s true. For example, I’ve just finished a project in New York City that I won in a competition for Social Housing from the New York City Housing Authority. In this project, 30% of the people involved are homeless.

I consider this a particularly important project because it’s not about a glorious skyscraper somewhere in New York City. It’s for people which has such a need to be able to live in in a dignified way.

I tried to show that even with little money, small budget, you can create something that has true value and change people’s lives.

Housing and inequalities: it’s such a tough issue.

I think I did already two projects of this kind in New York, and now I’ve applied in a third competition for skyscrapers also for New York City’s public housing.

That’s very important. Look at the whole world: people cannot afford housing anywhere. There is such income disparity, and I think that’s what’s really, really destroying cities because only a certain class of people can afford to live in the centres of cities.

Most of the skyscrapers in New York, the taller and newer ones, are dark because they’re used only one week a year. Manhattan it’s just for rich people to live, not for regular people, who have to live outside of the city.

Most of the people whom I worked with when I first started in New York, most of my colleagues, used to live in Manhattan. Now most of them live in New Jersey or in Brooklyn or far out in the boroughs. It’s hard to afford.

Obviously, I think that’s not unique to New York. Go to London, go to Paris, go to Milan. It’s hard in Milan to afford normal housing.

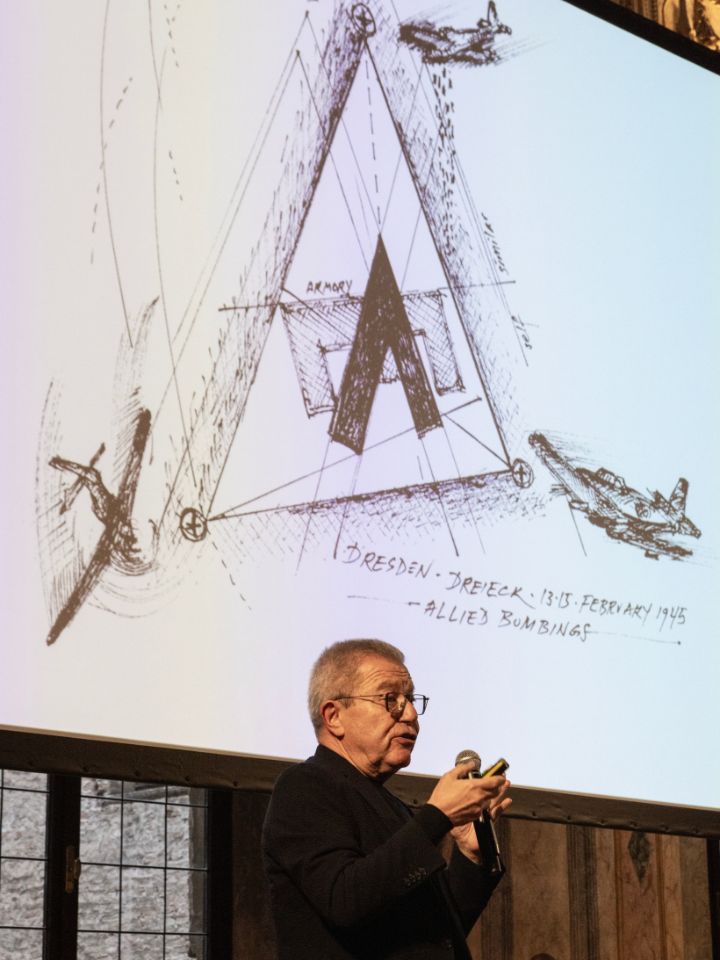

Speaking of New York, what was your approach to the 9/11 Memorial and how did you choose to convey the sense of this collective drama?

My idea was quite simple. It was not about architecture; it was about memory. I had to create a space. No one declared this as a sacred space, but 3,000 people died there. So, my project really took its cue from a question: what really happened there? What can and what cannot you build on that site?

I was the only one who said you should not build. How could you build where people died? It’s a very simple idea.

The project has changed over time compared to your original masterplan…

What for me was obvious, was not so obvious because every square centimetre of the site is extremely expensive and saying you’re not building is a very radical idea in that context. But you can still accommodate the millions of square metres in a different way, which is what I did. I used different symbolic ideas to organize the site.

Of course, there’s a lot of infrastructure and technicality, thus the project changed. But I had started with an idea about what the public would get, not the private developers.

Do you think you remained faithful to the architectural values you believe in?

I started and I ended with what I considered the most important client, which is the families of the survivors: they’re in many thousands, all related to the thousands of people perished there. And those were my client, not somebody else.

It’s important not to start with the developers and the builders. It all started with the spiritual idea of the place. The first thing was to speak with these people, to understand what was there, what had happened.

That was not just a land for development, although that’s how it was seen, because it’s in the middle of New York, in its most expensive area. And no one declared anything about the site being special, it was just another site. At the beginning, some people thought there would be a very small marker as a memorial. But I turned the entire area into a memorial.

And now, it’s actually the most visited site in the United States, more than any other, maybe 30 million people a year. One of the first destinations when in New York. Nobody had really imagined that.

Was the approach to the Jewish Museum Berlin different?

Yes, in that case it was more about the building. But I always started with the people, the culture, the religion. If you don’t start with this, I wouldn’t know what to start with.

What these two works have in common are trauma and post traumatic experience. So, it’s correct to say that the Jewish Museum Berlin can be considered as a bleeding wound, like something that must be seen to remember. The scar that can remind us of the past.

There’s literally a void running through the centre of the building. A void that you can feel and see. It’s a big museum, but its centre is not an atrium, it’s not a public gathering space, but it’s completely empty. It’s something which has nothing to do with the museum itself. In that way, it’s not a museum space. It belongs to some other dimension of the city, to Berlin.

Is there some project you’re working on now, also related to trauma?

I’m currently working on a very interesting project. You probably know the film set in Auschwitz “The zone of interest”, which won the Oscar. My client is the “Auschwitz Research Center on Hate, Extremism, and Radicalization”, who bought the house of Rudolf Höss, the man who ran Auschwitz, which is just outside the gates of the camp.

This institution wants to build a UNESCO-backed anti-hate centre on that site; and that’s quite different than a museum, because it’s no longer about memory, but how to act on the threats of today. There will be scholars working in it, and what better place than a place where you can see just across the crematoriums and the gallows.

It’s a sign of the different roles of architecture. It’s not like looking backwards to the trauma but looking at the contemporary sense of vulnerability and threats. So, it’s very interesting because it moves from memory to action in terms of the programme.

The relationship between memory and the present unfolds in your architecture through what some might call bold juxtapositions. Can you tell us more about the idea behind this approach?

I’d like to talk about the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, a fantastic project in my opinion.

I don’t think there’s a conflict between new and old. Most people think there’s a conflict, but there actually isn’t, if you are really interested in connecting different eras of history without nostalgia and without sentimentality, but with a sense of respect to the past and also with dedication to the present and to the future. So, there’s really no contradiction. Depends on how it’s done. And in that building, there’s really a very delicate connection between the different wings, the different histories from 1920 to today.

It’s such an interesting approach also for our students of the MSc degree in Architectural Design and History, because they study history to work in the history.

Most people consider context as something which is dead, in the past. But the context is a living context. As so, you cannot treat it like it’s dead. You have to create the right relationship with the past.

As an example, I’m working on a very unusual project in Antwerp. There’s a very iconic Art Deco tower right next to its cathedral, the Boerentoren. Built in 1930, it was the first modern sort of American skyscraper built in Europe. My client bought the building and wants to turn it into a museum of arts.

It’s a challenging intervention because it’s protected, it’s a monument of the city to respect.