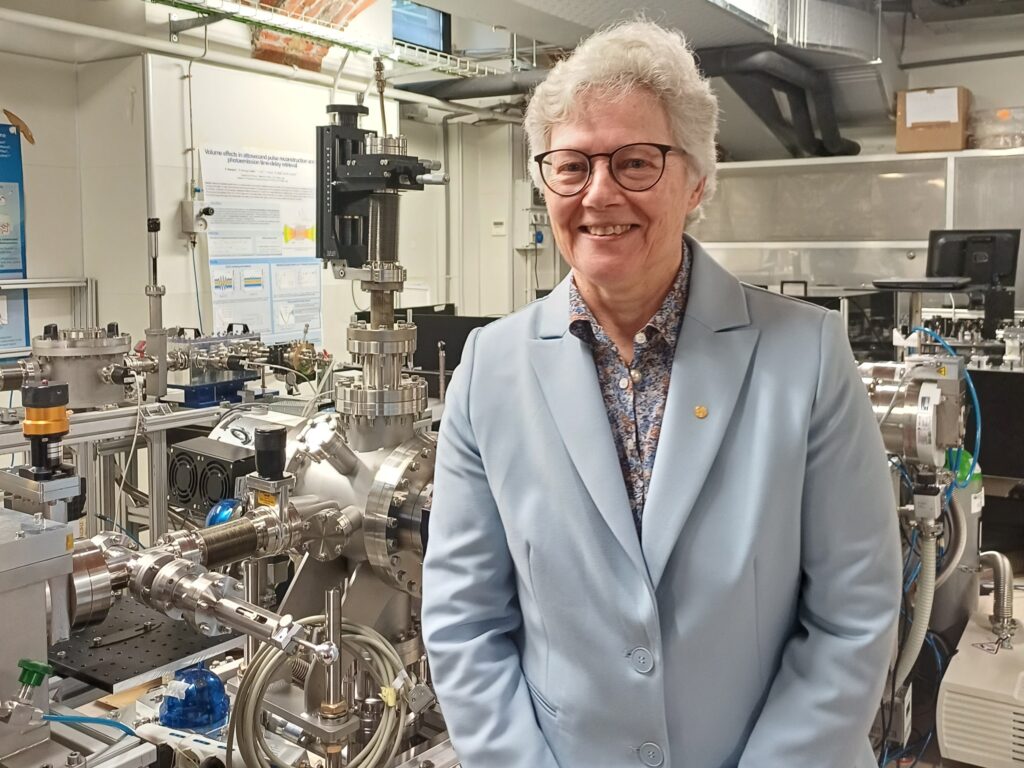

Anne L’Huillier, a French physicist specialising in atomic physics, became the fifth woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2023. She was awarded alongside Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz, “for experimental methods generating attosecond pulses of light for the study of electron dynamics in matter.” We had the privilege of meeting her ahead of her lecture on 22 April 2024 at Politecnico di Milano, organised by the Department of Physics. During her talk, she outlined the path leading to the generation of attosecond pulses and highlighted the crucial role of high-order harmonic generation in advancing the frontiers of atomic and molecular physics. This journey across the frontiers of ultrafast science unveils new insights into electron dynamics and opens the door to groundbreaking applications in attosecond spectroscopy and precision metrology.

Your career started in France and later progressed in Sweden. How do you assess the importance of international mobility in research?

«That’s a tough question. I went to Sweden for personal reasons, to join my husband who is Swedish. However, I can say that international mobility is quite important to me, particularly within Europe. It is incredibly enriching to experience different countries, and the European Community strongly encourages this through initiatives such as Erasmus, and later, programmes like the Marie Curie networks, which offer excellent opportunities for researchers.

Italy faces significant challenges in attracting international talent and retaining its researchers. What strategy do you think should be adopted?

Italy shouldn’t focus on retaining talent; I believe it’s more appropriate to view it from a European perspective. So, if an Italian goes abroad, foreigners are coming to Italy at the same time, balancing the exchange. I see this as an important and positive trend. This level of mobility across Europe benefits everyone».

A researcher’s career, especially in the early stages, faces various pressures, such as competition, the need to publish frequently and rapidly, and job insecurity. How can these aspects be reconciled?

«In my experience, perhaps things were easier when I was younger. I don’t recall the same pressure to publish 40 years ago. I believe it is crucial to uphold scientific rigour. Passion and motivation are essential for a successful research career. There will inevitably be difficult moments, and you must be deeply passionate and motivated about your work to avoid giving up».

The scientific community still has much progress to make in achieving full gender equality. There is also talk in academia about enhancing the inclusiveness of scientific teams. What impact do you think these issues will have in the future?

«I cannot answer in detail, but I do believe that diversity in research is important. It is crucial to have people of different genders and backgrounds. This enriches the discussions, making them more profound when participants bring their varied perspectives.

Regarding women in science, I have noticed improvements over the years. In the 40 years I’ve been conducting research, I’ve seen clear progress. For many years, I was the only woman on a team of men, but that’s no longer the case – now, more than 30 per cent of my team are women.

There’s also been progress in the number of female Nobel Prize winners in physics. We are now five, with three awarded in the last five years, so while it’s still a small improvement, I believe this marks the beginning of an upward trend.

What do you think about the so-called “leaking pipeline,” the phenomenon where, despite equal numbers of boys and girls entering the field, the number of women steadily decreases as their careers progress?

That’s an excellent question. I think it’s difficult to fully understand why this happens. One reason, I believe, is that raising children demands significant time and attention. This affects women’s careers more. I think society should help.

In Sweden, for example, I find it easier. There are good childcare options available after school, and it’s more acceptable to finish work earlier to pick up children compared to other European countries. Society needs to change, and partners need to share the responsibilities. There’s still work to be done to make it easier for women to remain in research careers and not drop out too soon.

What were the best and most challenging moments in your scientific career?

There were two “best moments.” The first was in 1987 when we discovered high-order harmonic generation. That discovery was crucial for me and remains vividly in my memory because it shaped the course of my career. The second was receiving the Nobel Prize – an incredibly emotional and happy moment.

A difficult period in my career came when I moved to Sweden. I left a good position in France, and while it was a personal decision, it was challenging on many levels. It took me two years to adapt to the Swedish academic system, during which I frequently travelled between the two countries.

Another tough phase occurred in the late 1990s when we suspected the existence of attosecond pulses but struggled to measure them, and the methods we were using did not work. I was eager to develop applications for the harmonics, but even that wasn’t going well, and there was little interest from the wider scientific community. In every scientist’s career, you go through tough periods, but those are the times when persistence is the key, and you must keep pushing forward.

So, is this the advice you would give to a young student or researcher entering this field?

Yes, definitely – passion first, and then persistence.

What do you think will be the main areas of application for the technology developed around the generation and use of attosecond pulses?

I believe this field has potential applications in many areas. I think research is still crucial, we have not yet reached the stage of everyday applications.

One of the major areas where I see this technology being applied is in studying electron dynamics in complex systems. This type of research is being conducted extensively in Milan, where scientists are examining what happens in large molecules, such as biomolecules, and in condensed matter. I believe we’ll see practical applications emerge in these areas in the coming years.

Additionally, there is an industrial application already being developed – using harmonics as a measurement tool for silicon-based chips and integrated circuits. This is particularly interesting because it falls within the extreme ultraviolet wavelength range, which has many available frequencies. It allows for metrology in the next generation of computers and smartphones, where components are sometimes just a few nanometres in size. The semiconductor industry is already developing this technology.

You’ll soon be addressing a large audience of young students. How important is teaching to you?

Teaching is extremely important to me, as it brings balance to a research career. When you share knowledge and enthusiasm with students, it provides a great sense of equilibrium.

Research can often be frustrating, and there’s a risk of losing direction, but teaching offers immediate feedback. Through the eyes of students, you can see the relevance and value of what we do for society. I encourage everyone to combine teaching and research.

And what will you be discussing this afternoon?

This afternoon I will provide a 40-year historical perspective on this field of research. I’ve had the privilege of being involved from the beginning, so I’ll explain how it all started and evolved.