This month on Frontiere, we continue our exploration inside the research laboratories, alongside the people who work in these spaces daily.

The Sound and Vibration Lab (PSVL) is the Politecnico interdepartmental laboratory dedicated to the study of sound in its various forms. The lab comprises several experimental spaces, organised into two main centres: one at the Bovisa Campus, which focuses on applications in industry, transport, and construction; and the other in Cremona, at the Violin Museum, which specialises in musical acoustics.

Today we are in Bovisa, where Roberto Fumagalli, laboratory technician at the Department of Energy, will unveil some of the secrets and stories of this remarkable place, where sounds are measured and their interactions with the world are analysed.

Hello Roberto, thank you for welcoming us into your lab. Let’s start by learning more about what you do.

Sound and vibrations have a significant impact on the technological applications we use daily, which is why they are attracting growing scientific and technical interest.

Here we work with decibels. We measure, test, and study the reduction of vibrations and noise in work and domestic environments, vibrational and acoustic comfort of transport systems, noise pollution from road and rail traffic, improvement of acoustic conditions in indoor and outdoor spaces, and experimental techniques and methods for analysing and reconstructing acoustic fields.

So, you are the Politecnico’s go-to centre for the world of sound.

The PSVL Laboratory pools expertise from the involved departments to promote a multidisciplinary approach to research.

In addition to the Department of Energy, where I work, the lab includes the departments of Mechanical Engineering; Electronics, Information and Bioengineering; Aerospace Science and Technology; Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering.

We have established a unified department dedicated to research in vibroacoustics, aeroacoustics, applied acoustics, architectural acoustics, vibration and noise control, sound processing, musical acoustics, psychoacoustics, and music information retrieval.

How did you become involve with this lab? Have you always had an interest in acoustics?

I initially attended a classical high school and later enrolled in construction engineering. It took me a while to graduate – I took my time. [laughs]. For my thesis, I worked on vehicle acoustics with Professor Livio Mazzarella, who was overseeing the lab at the time. I had a passion for noise even then.

In 2005/2006, there was a possibility for a Research Fellowship on the psychoacoustics of washing machines with Professor Mazzarella, which included several departments, such as Mechanical engineering under the then Deputy Head, Ferruccio Resta. I spent a couple of years away from Politecnico, specialising in environmental acoustics in a different lab. In 2010, I returned with research grants to help the acoustics laboratory.

In 2017, I started working with Mario Motta’s Relab, focusing on heat pump acoustics.

Currently, I coordinate PSVL activities and engage in outreach work.

I am intrigued by the concept of psychoacoustics. Can you explain what you mean?

Psychoacoustics is a fascinating field that explores the psychology of sound perception.

When I said, “I used to listen to washing machines,” I wasn’t joking. In the past, when purchasing a washing machine, you couldn’t know what noise it would make until you got it home. We were intrigued by what testers could hear when the machine was in operation, including their mood at the time.

Nowadays, our mechanical colleagues test other household appliances, like coffee machines and kitchen hoods. We assess how these objects sound in our lab, aiming to make them as pleasant as possible if complete silence isn’t feasible.

Is the goal always to minimise noise?

Not necessarily. The absence of sound isn’t always positive, as objects often make noises to provide us with information.

For instance, how many people have failed to notice an electric car just a few centimetres away? To address this, electric and hybrid cars now emit sounds, like a gentle hissing, to signal their presence.

About the automotive industry, psychoacoustics plays a significant role in marketing, doesn’t it?

Absolutely. Car commercials focus less on performance and more on evoking emotions. It’s these emotions that drive purchasing decisions. For example, the sound of a car door closing is crucial—it must “sound solid” to convey a sense of security.

Sometimes, a particular noise triggers stereotypes that we unconsciously adopt. Here’s an example: for an experiment, we played the sounds of four different door locks, attributing two to German brands, one to French, and one to Italian. We then asked participants for their impressions. The result was that the German locks sounded the most solid, the French were average, and the Italian locks were deemed the least impressive. The twist? We had used the same door each time.

These psychological elements are carefully studied before launching an advertising campaign, and our tests help analyse such cases. Well-known car manufacturers consult us on the sounds their car buttons should make.

How are noise perception tests conducted?

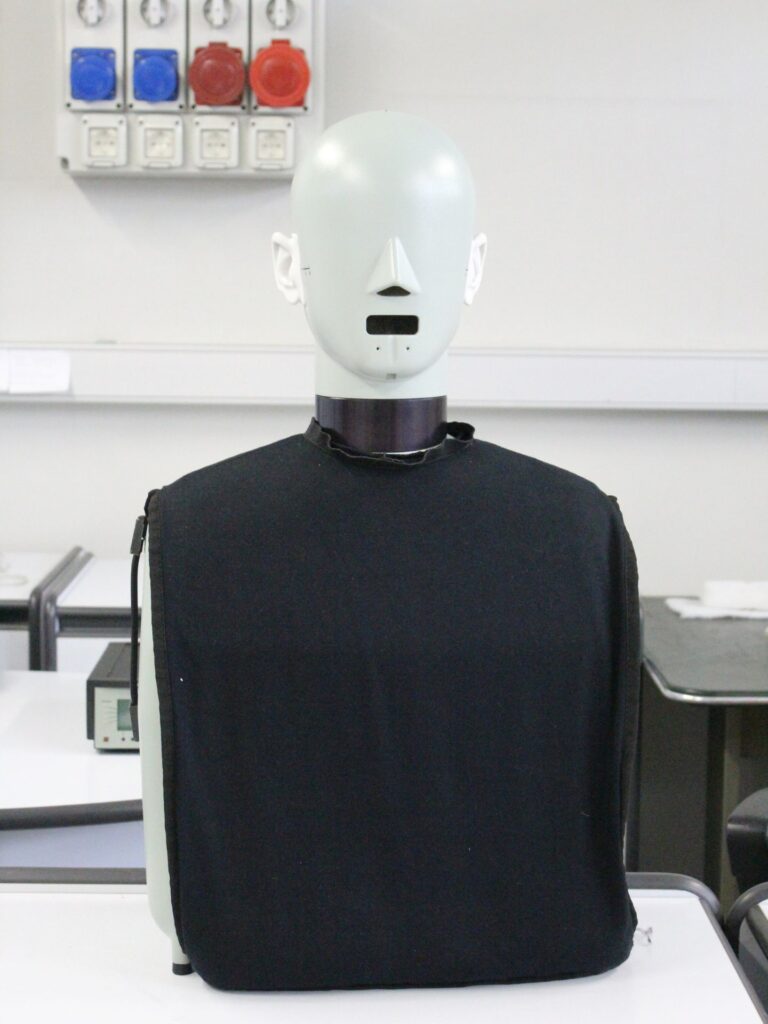

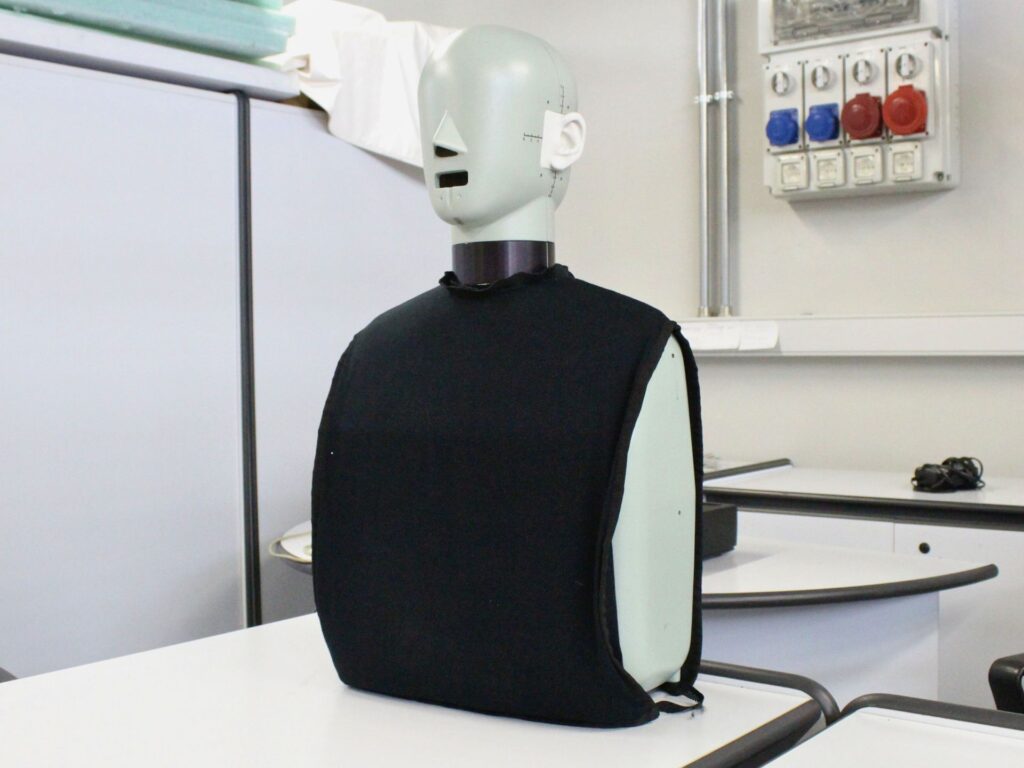

One traditional yet highly effective tool is the binaural dummy. Despite being around for 40 years, it remains highly reliable. This dummy has microphones placed in its “ears” and a movable head for accurate measurements.

The perception of noise varies depending on location and age, correct?

Yes. For instance, a professor of mine once researched in a desert region in the Middle East. There, 70-year-olds had auditory sensitivity comparable to our 20-year-olds, due to constant exposure to silence. I found this research fascinating, especially as my father had always worked in an extremely noisy workshop.

One of the most important places in this lab is the anechoic chamber.

You may have already seen me in this room, notable for its foam-like wedge coverings. It’s perhaps the most unique space in the lab, often showcased to visitors during science outreach events like the International Engineering Festival.

This chamber is among the quietest places on earth. Some claim it drives you mad, even though I’ve grown accustomed to it. Many people request to experience it, from thesis students to influencers wanting to film their videos. These requests are assessed, with research needs taking priority.

So, what is the principle of the anechoic chamber?

There are two main methods for studying sound. The sound field must be precisely defined to measure sound power in decibels.

Measurements can be taken in reverberation chambers, where sounds reflect off the surfaces, similar to how sound behaves in a large cathedral. In such spaces, sound pressure is nearly uniform throughout.

Alternatively, the sound field must be unobstructed and free for sound to propagate naturally. The anechoic chamber is the best simulation of a free field. When the chamber is isolated from external noise, conditions are ideal. Among the top university chambers in Italy is the one in Ferrara.

Can you show us how it works?

As you can see, the chamber is completely lined with foam-like wedges, which are made from polyester fibre to avoid dust. These wedges absorb the sounds of any objects in the room, allowing us to determine the “true” sound of those objects.

[He does some tests, popping a balloon or hitting two sticks together]

What do you hear? Is it the sound you expect? Some answer yes, others say no. As a Zen master would say, there is no definitive answer. [smiles] To put it more accurately, the right answer would be “it depends.”

What are some of the most unique uses of the room that you’ve overseen?

David Romano, the first violinist in a Naples orchestra, plays a 17th-century instrument. Once he had to create an acoustic shell with wooden slats for outdoor performances. He experienced what his instrument sounded like in the chamber and theatre.

Like the balloon test, the concept of “real” sound is often more psychological than objective. Our expectations can be validated or challenged through trials in the anechoic chamber.

Have many musicians visited the lab?

Quite a few. For example, Franco Mussida, one of the founders of PFM and CPM, Centro Professione Musica, with the help of Diego Maggi, worked with us on a project to create a musical composition to mark the hours at a Swiss spa. They came here and sampled their instruments. Diego spent a good half-hour in the chamber.

Percussionist Elio Marchesini from La Scala was involved, trying out a range of instruments including timpani, various bells, marimbas, and plates.

Working with musicians is fascinating because of their exceptional sensitivity and unique vocabulary—they speak of timbres and colours.

We worked on an acoustic shell for the Stresa Festival, with Professor Imperadori’s thesis students who contributed to its design. It was a unique experience; we took the dummy out for testing an “acoustic catapult” designed by architect Michele De Lucchi. We also met Bollani. The goal was to avoid using microphones and rely on the acoustic catapult, but the sound engineer had to discreetly use some microphones and adjust the volume to ensure the sound was always clear, without the audience noticing the technical enhancements.

What about the lab in Cremona?

The Cremona lab is located near the Stradivari Museum. Did you know that a violinist needs to play their violins every 15 days to keep them “alive”? They have their own anechoic chamber, because moving a Stradivari from Cremona to Milan would be unthinkable due to the extreme security measures required.

How has sound performance evolved over the years?

Are you familiar with room acoustics? It’s the study of how sound behaves in different environments. For example, theatre acoustics are particularly intriguing.

The principles of sound reproduction on audio systems stem from these studies. Sound is always perceived by the brain: even with my eyes closed, I can identify the direction from which a sound is coming. This is possible because our two ears are spaced apart. The physical position of the head alters the sound, and the brain processes this information to pinpoint the sound’s location.

So, are dummies used to record these 3D audio tracks?

Yes. When I make a binaural recording, the sound travels from inside the head to the outside, creating a “3D” effect. This technique is commonly used in ASMR.

By placing microphones in the ears of dummies, we can achieve binaural recordings. Silicone ears can also be used. The data is put into two channels, and our brain reconstructs the sound experience. Obviously, these recordings are meant to be listened to with headphones.

Has the dummy evolved over time?

Yes, it has. At the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering, they have a machine that scans the head and adjusts the recording to match a specific head shape.

Have there been recent innovations in recording techniques?

There was a golden age of recording, particularly in the 1940s when recordings were monophonic and required the singer to be close to the microphone. The microphones used in our lab differ from those used in music production. Our goal is to capture sound in its purest form, focusing on the tone and spectral components as we perceive them.

There are countless factors to consider. Today, we use Ambisonic systems. Immersive sound technology allows for 3D recordings that can be oriented in space. By rotating the dummy, it simulates turning your head in real life. These techniques allow to virtually orient your head in any direction with a single recording, eliminating the need for a rotating dummy.

What is an acoustic camera?

An acoustic camera is akin to a thermal camera but for sound. It uses different colours to visually map where a sound is coming from. This technology is often used in wind tunnels. State-of-the-art acoustic cameras have replaced older intensity probes.

For 17th-century violins, laser vibrometry is used. This technology measures the vibrations of the soundboards, as sound is essentially vibration.

What is the future of sound rendering?

The future may involve integrating Dolby sound directly into your head. This concept has been explored with the Earound system, which uses digital filters. Some films have been made with an Earound track to enhance the sound’s spatiality. We have worked with Matteo Maranzana, a professional from the dubbing world, to develop a system that brings Dolby Surround sound into headphones.

Only time will reveal whether our film audio experiences will be revolutionised.

Can you recommend some reading to dive into the world of acoustics?

I recommend Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, by Oliver Sacks. It provides profound insights into how music, emotion, memory, and identity intertwine and shape who we are.