For those who are part of the Politecnico di Milano community, Camillo Boito represents the story of our founders, those to whom we entrust the task of defining the roots of the Milanese and Lombardy traditions, which today we carry with pride into our international dimension. That is why we want to tell his story in Frontiere, along with the influence he had on our university and on Italian architecture.

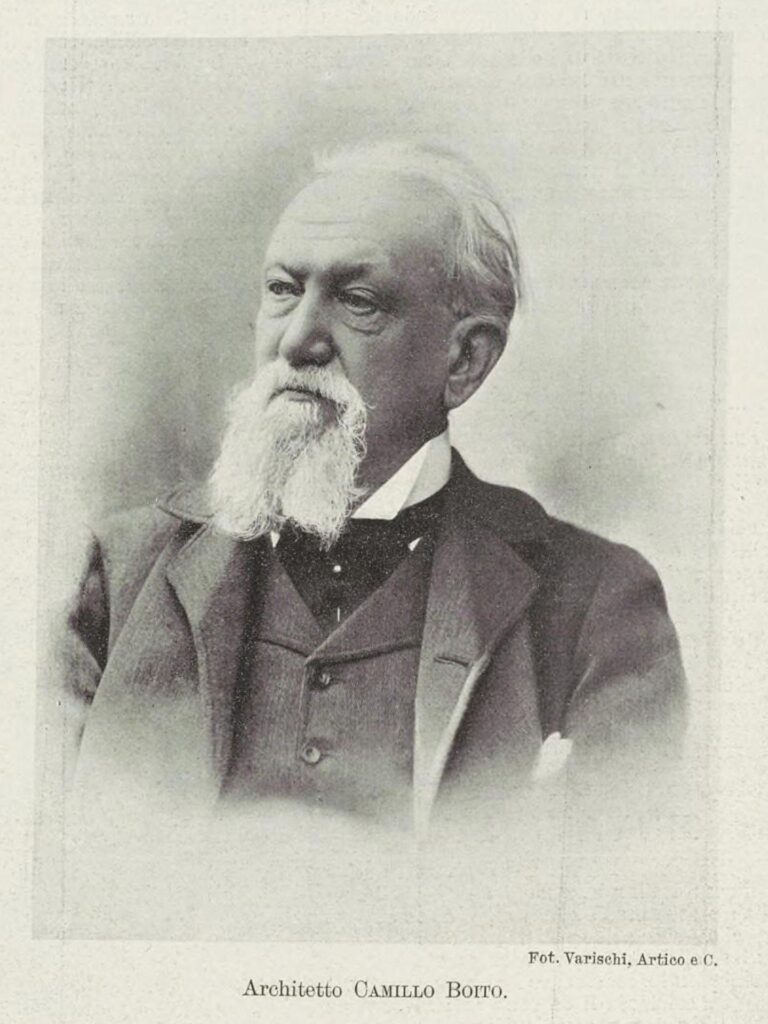

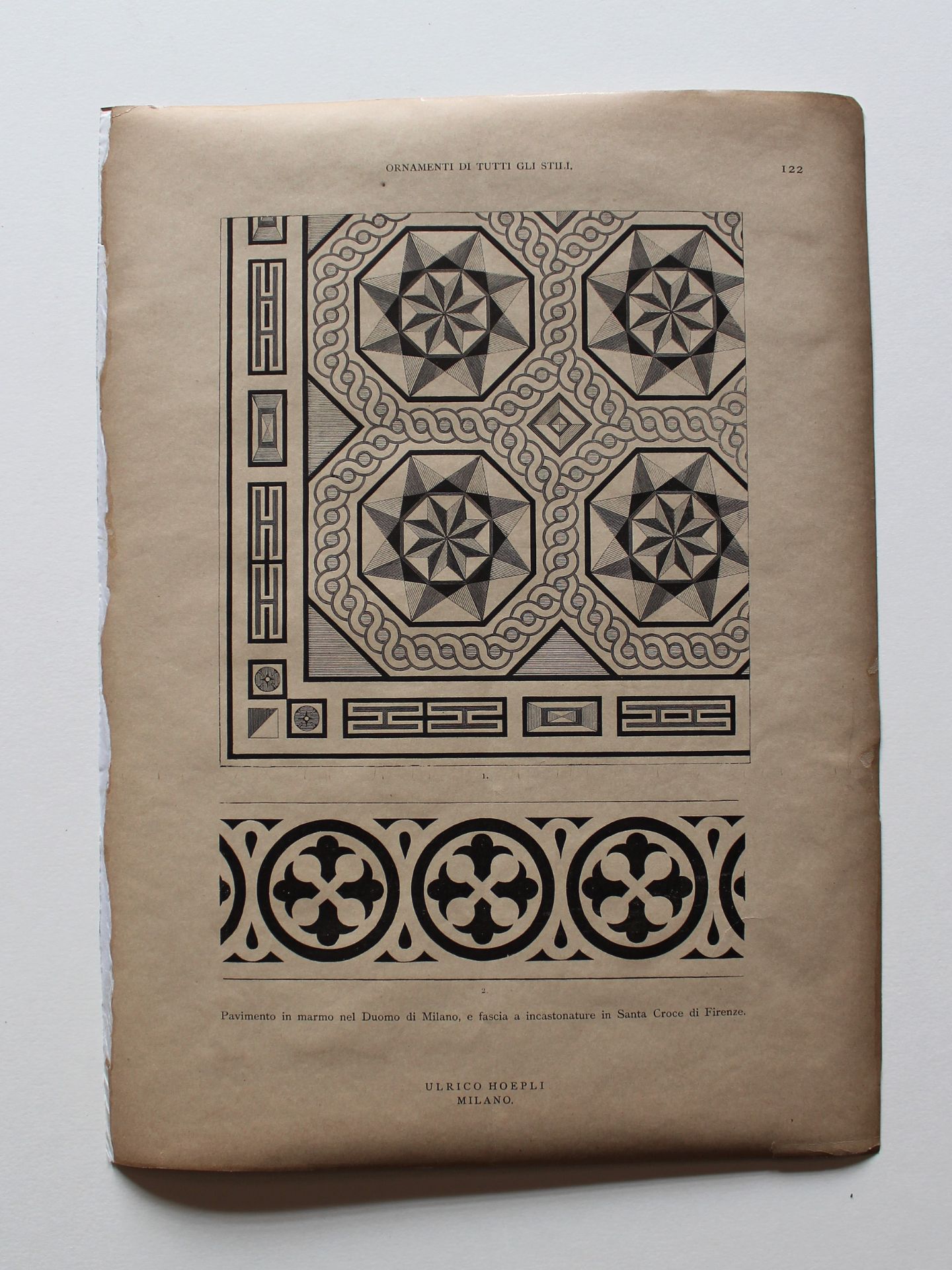

Camillo Boito was born in Rome in 1836. He attended courses at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, including that of Pietro Selvatico, which was fundamental to his training. Selvatico wanted him as an adjunct professor to the Chair of Architecture in 1856. At the end of the year, Boito travelled to Tuscany and Rome to study Cosmatesque art and Gothic monuments. After returning to Venice in 1859, he soon joined his brother Arrigo in Milan; in 1860 he was appointed Professor of Architecture at the Accademia di Brera, becoming one of the major promoters of the renewal of Italian architectural culture. During that period he also became President of the Academy, a position he held until his death. At Brera, among others, Luca Beltrami, Luigi Broggi, Gaetano Moretti and Giuseppe Sommaruga were to be his students.

At Politecnico di Milano

When Francesco Brioschi inaugurated the first academic year at Politecnico in 1863, the institute was divided into two sections, namely civil engineering and industrial engineering. But it was only two years later, in 1865, that a third section was added to the former: that of architects.

The very director of that operation, supported by Brioschi, was Camillo Boito himself – and he was not yet 30 years old. His challenge, at the forefront in Italy and in Europe, best testifies to the design impetus which is peculiar to the ‘Politecnico spirit’: he aimed to integrate the Accademia artistic courses and the Higher Technical Institute scientific courses, so as to train a professional figure capable of effectively responding to the new needs in the construction sector.

Boito became a lecturer at our University in 1865, with the Chair of History of Architecture and Surveying and Restoration of Buildings; he taught Classical and Medieval styles from 1867 and Architecture from 1877 to 1908. He directed the Faculty, now the School of Architecture of Politecnico di Milano, for over forty years, from its foundation to the early 20th century, and among his students we can cite numerous architects of modern Milan.

The practical, design and intervention activity.

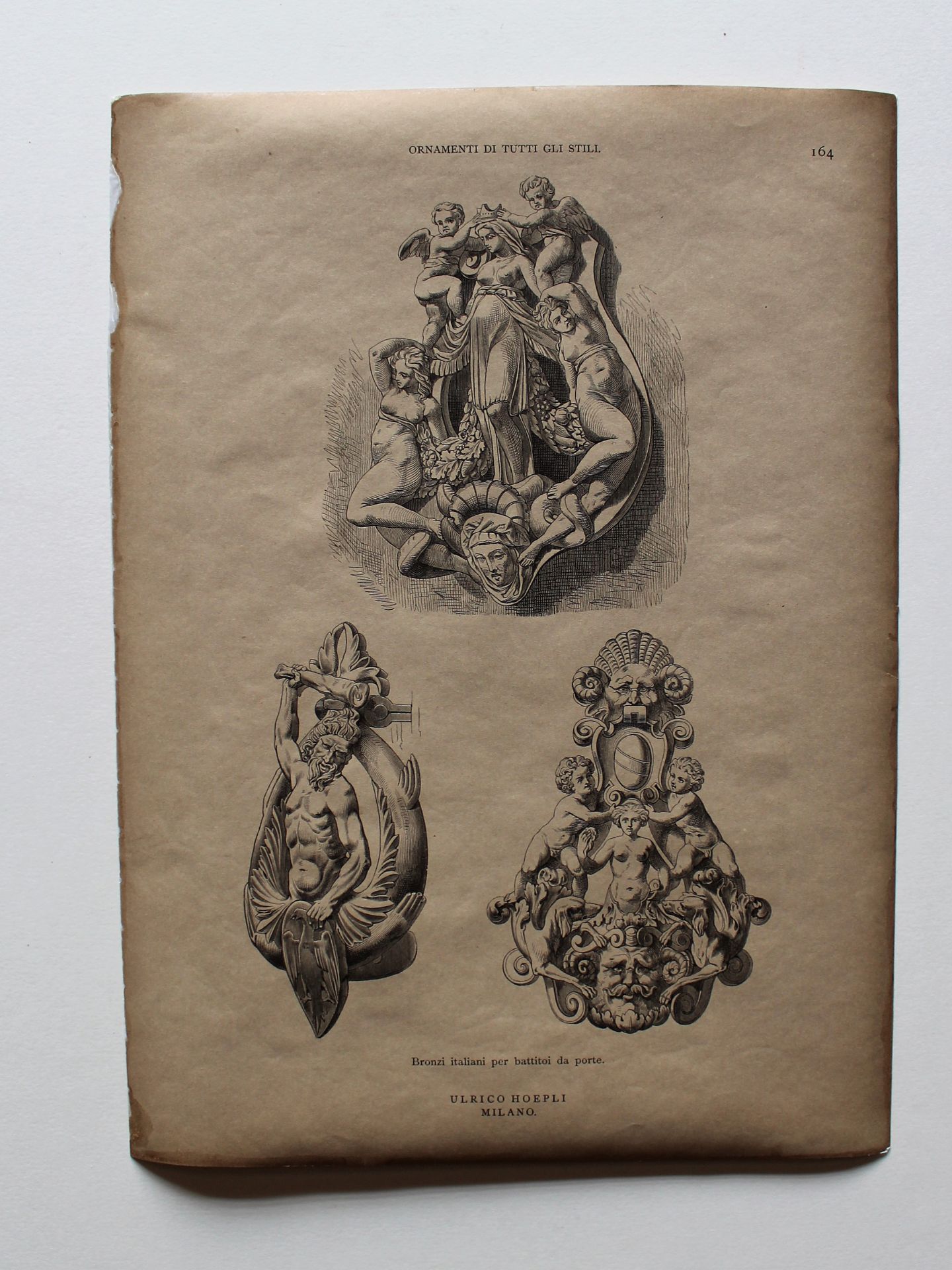

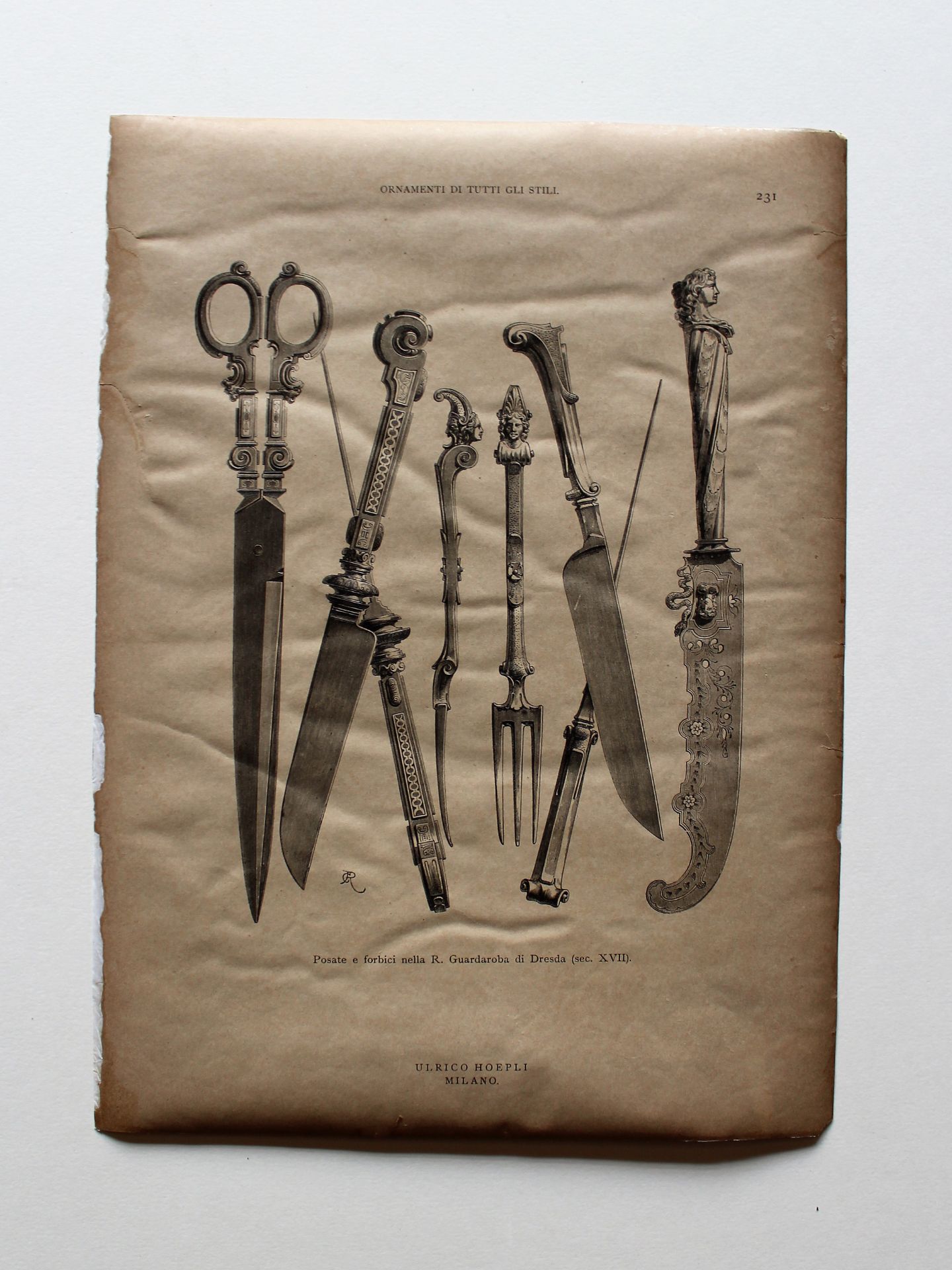

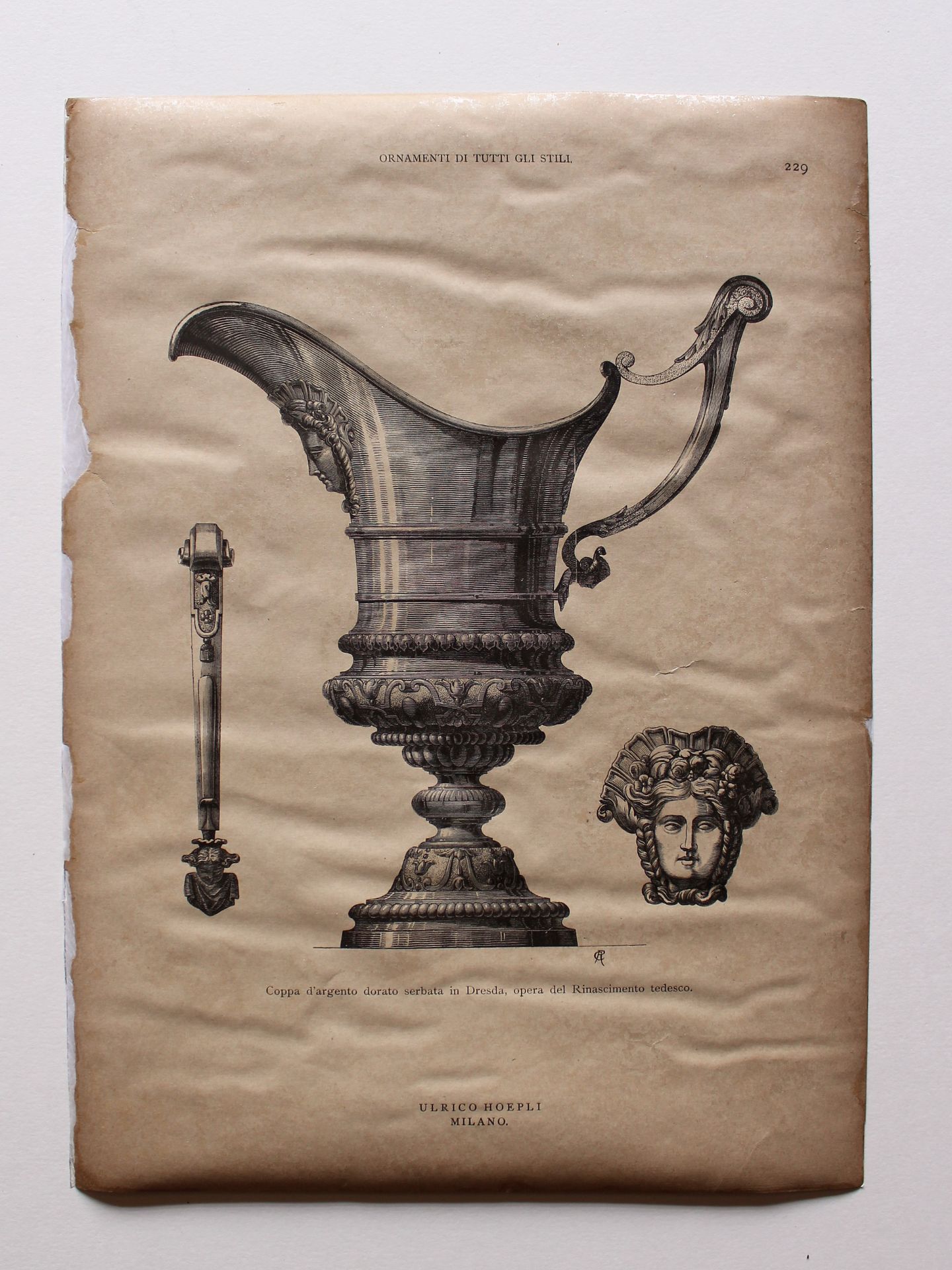

As an architect, Boito consistently advocated the need to abandon eclecticism to cultivate a new Italian style in which modernity was married to tradition, understood as intended by Gustav Mahler: ‘Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire’. For Boito, the past is a need for the soul: architecture must be intimately tied to the past for it to be a monument of an age and a people. National character comes from historical character as well as natural character. This is why he found the essence of the ‘language’ of Italian architecture in 14th-century Lombardy and municipal manners, which for him are profoundly linked to the history of our country.

His first intervention, the restoration of the Pusterla di Porta Ticinese, dates back to 1861. The single-arched gateway, erected in 1171 and flanked by two towers to which houses had been attached, was freed and transformed by the opening, for pedestrian passage, of two lancet side arches at the base of the towers. The choice reveals a complete adherence to the still romantic image of the Middle Ages.

In Gallarate, in 1865, he built the enclosure chapels and the Ponti sepulchre in the new cemetery, marked by his characteristic constructive sincerity. In 1869, again for Gallarate, he prepared the design for the civic hospital (finished in 1874), which revealed his maturity and his evident search for a linguistic renewal, along with his tendency to draw a reason for aesthetic expression from structural elements.

In 1872 he won the competition for the restoration of the provincial palace in Treviso, but his project was not executed. Between 1873 and 1880 he carried out three major works in Padua: Palazzo delle Debite (1873-74); the arrangement of the square, the entrance building and the staircase of the Civic Museum (1879); the primary school at Reggia Carrarese (1880). Only the latter building is closer to his innovative ideas – perhaps because free from binding environmental situations.

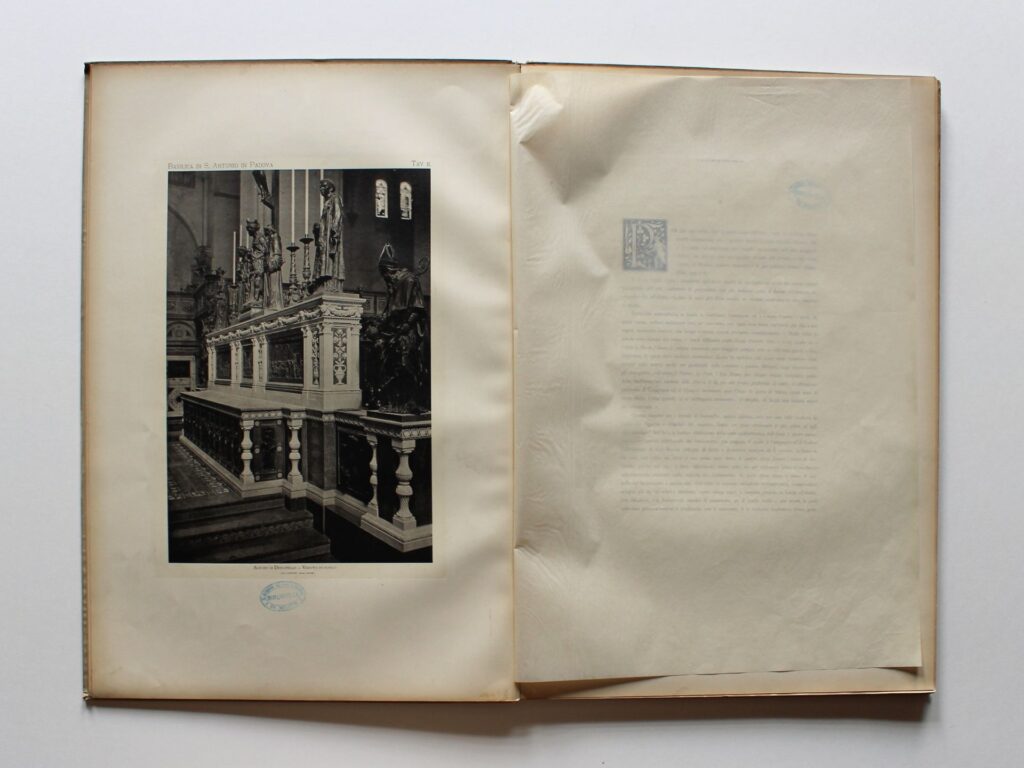

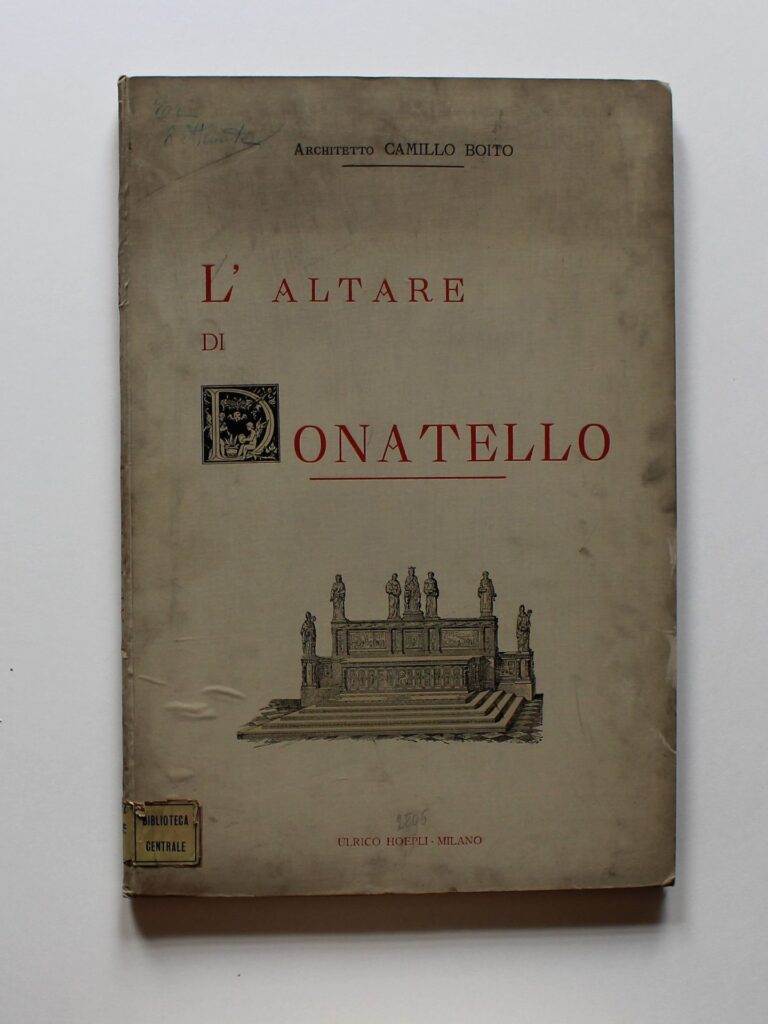

Long and thoughtful was the reinterpretation effort for the recomposition of Donatello’s altar in the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua. Although he was convinced that he had restored Donatello’s sculptures to their original location, later critics made it clear that he had included sculptures that were not originally part of the altar and added that he had completely ignored the problem of Donatello’s architectural structuring of the altar due to a misreading of the sources. He also designed the bronze doors for the Basilica del Santo in 1895.

The primary school in Via Galvani in Milan

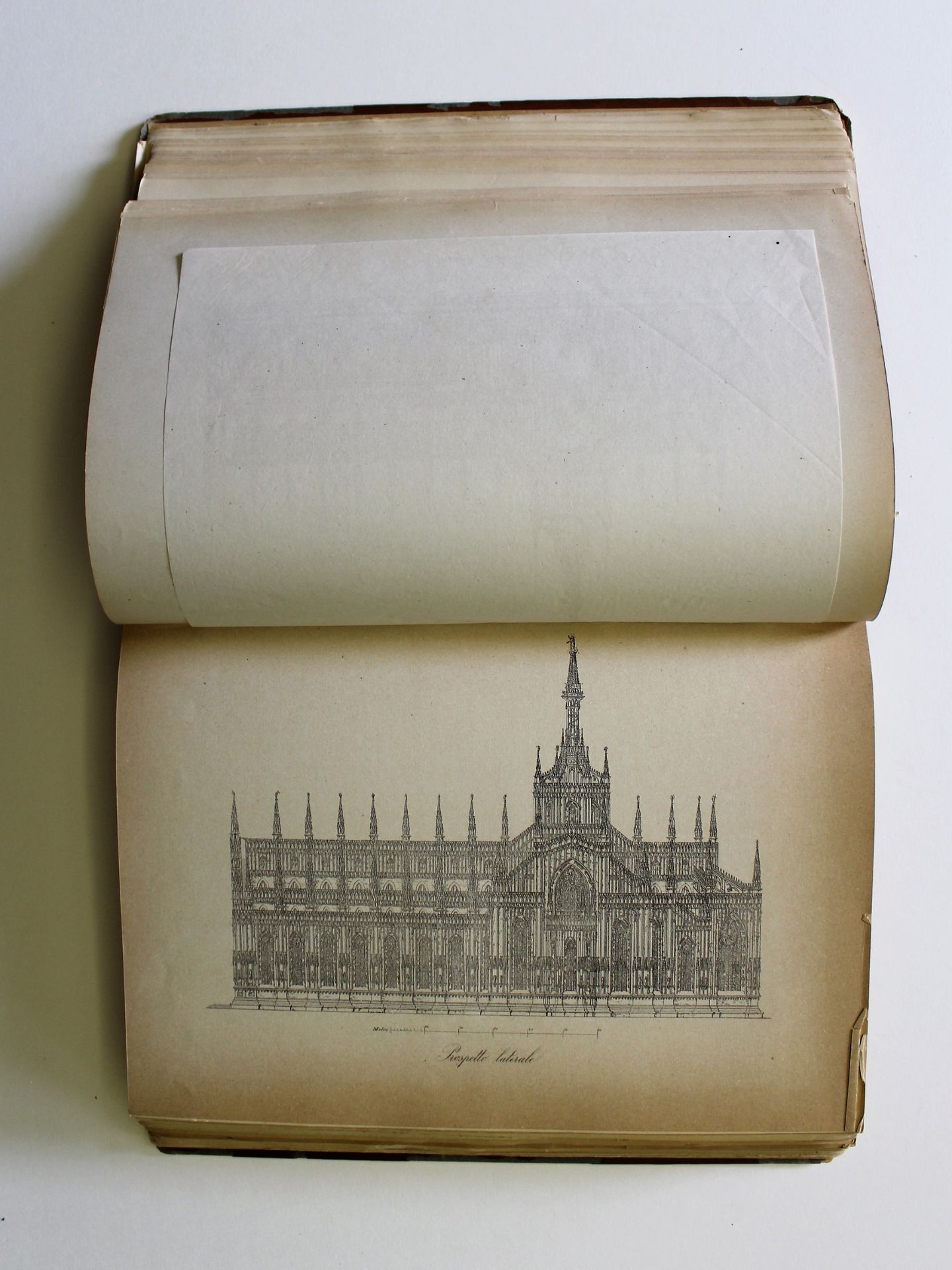

The primary school in Via Galvani in Milan, dated 1888, highlights a development and deepening of functional and distributive themes that apparently reached definitions of undoubted clarity. The building exalts the constant characteristics of a perennially indeterminate suburbia, nevertheless capable of absorbing and resisting violent urban transformations with an identity of its own, from the first industrial nuclei and buildings for assistance and education to the upheavals engendered by the large factory at the Central Station, on to the modern tower densities of the business centre.

The urban dimension of this building enhances the apparent simplicity of the distribution scheme, with its play of volumes aligned along the street front, in a large volume, but still conforming to the characteristic measurements of the Milanese fabric. The long body of classrooms is broken up rhythmically by the service rooms, with the central body of the gymnasium and special classrooms, the entrance heads with the stairwells and other special classrooms. On the inside, the stairwells open up as empty intermediate spaces, allowing multiple perspectives of the very long floors that divide the corridor levels.

Giuseppe Verdi Retirement Home for Musicians

Boito’s last architectural work was the Giuseppe Verdi Retirement Home for Musicians in Milan in 1899. In the treatment of the wall surfaces and decorations, echoes of Pre-Raphaelite motifs and a measured adherence to the floral style in the use of natural materials and in the free combination of stylistic memories of different eras can be perceived.

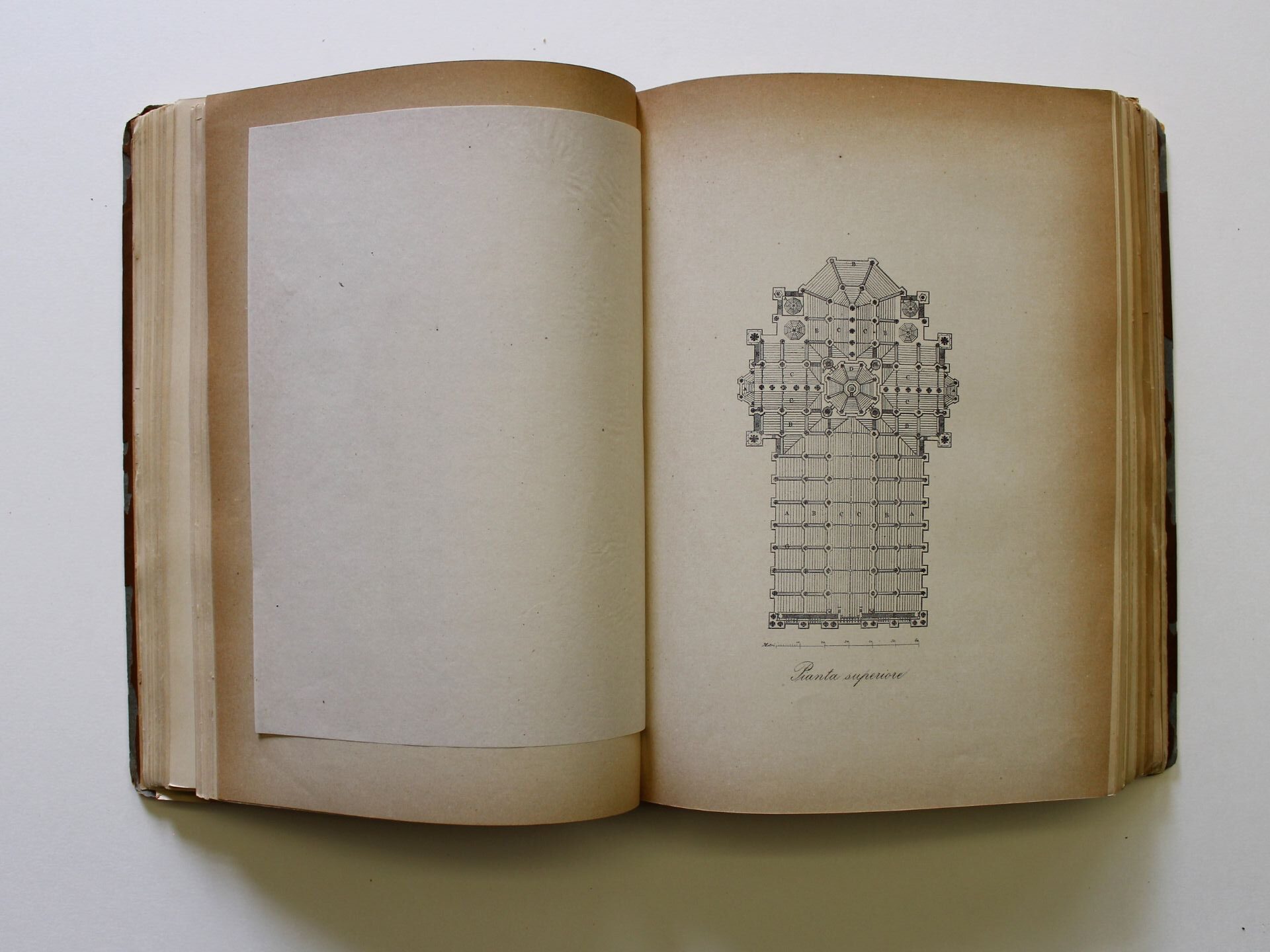

In this last building, an absolutely new planimetric and distributive ‘twitch’ is represented. If the first project followed a geometric – albeit elaborate – layout known in its genesis also symbolically, the second project rested on almost dissonant, anti-romantic logic and on volumetric deviations in the corners, in the sides, in the elongated body, in an accelerated perimeter perception. The architectural structure is generated from an initial symmetry which is then kinematically destroyed by the ever-shifting corner view of continuous suburbia, under construction, in a new city.

This stereometric character is a significant prelude to the futuristic spatial combinations that introduced him already in the 20th century, a momentum that Boito could no longer hold back, not even with respect to the scenographic scaffolding with which he felt he had to cover the façade, almost as a homage to romantic sets and settings – the Shakespearian climate transposed by his brother Arrigo into Verdi’s librettos – perhaps well beyond Verdi’s needs, mandate and intimate taste.

Boito as a narrator

It is worth mentioning Camillo Boito as a Lombard Scapigliatura author, above all of two volumes of short stories: Storielle vane (1876) and Senso. Nuove storielle vane (1883). Many of us are indirectly acquainted with him in this capacity: as it is well known, from the eponymous story in the second collection Luchino Visconti drew inspiration for his film, where he accentuated the intimate, bitter decadentism of his narrative.

Between the lines of his well-known stories we distinguish a more or less explicit tension that cannot be explained but by moving from his background as an architect; thanks to this very tension, we can actually explain, almost in a kind of psychology of transfer, certain central aspects of his architectural work.

Despite his success was attested by numerous editions, his critical success was hard-won and somewhat late.

Boito died in Milan in 1914.

Boito’s Legacy

Camillo Boito lives in the memory as an innovation devotee and at the same time a defender of the continuity between the history of our country and architecture, which is called upon to express both the spirit of its time and its deep roots at every stage of its development. He was a true intellectual: to him architectural activity was not an end in itself, but rather an important aspect of a political, philosophical and literary battle, fought with constant and patient faith to ensure that a newly created nation could become a part of Europe at the forefront of culture and art. He wanted to give architecture a civil conscious role.

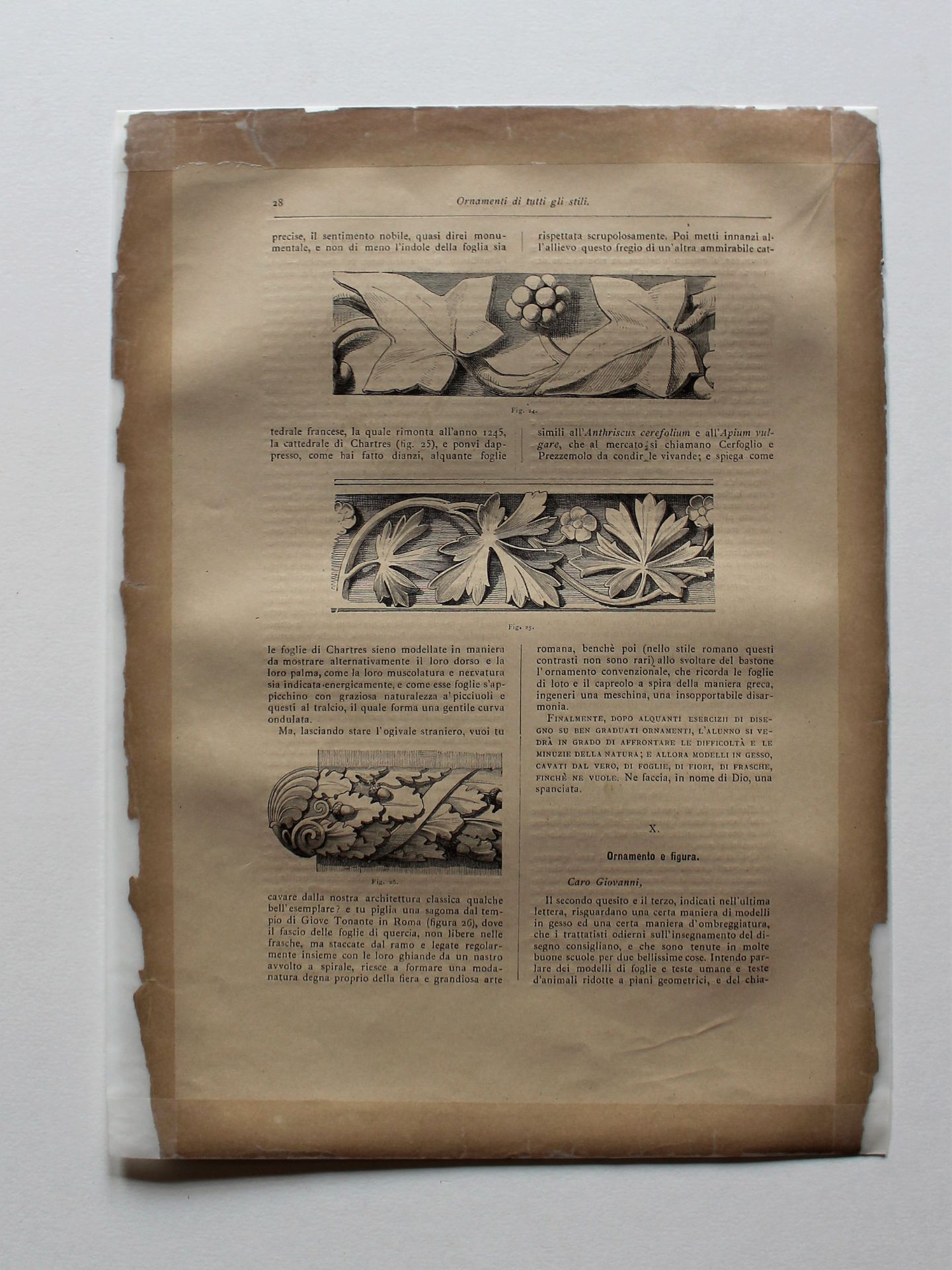

Within the Accademia, Boito fought for the invention of a modern methodology of restoration, for adherence to the ‘industrial’ problems of artistic production and for an expressive renewal of architecture more closely linked to the built material, ‘romantically’ understood in the recovery of Romanesque masonry technique and almost forgetting iron – a material which was way too used in modern engineering.

Within Politecnico di Milano, Boito sought to consolidate a new culture which could be true to the architectural tradition (both classical and romantic) while also necessarily contributing with technical knowledge. Above all, he deemed a rational discipline open to the problems of the new city, grasped by ‘civil’ engineering, was essential and tried to set new tasks for architecture, regenerated in neo-medieval municipalist stylistic features as the characteristics of the Italian city, against a latent and continuous delegitimisation, inserted under the empty decorations of current eclectic and classicist, mannerist and apparent architecture.

In his farewell ceremony from teaching, held on 21 March 1909, Brioschi’s successor, Giuseppe Colombo, celebrated Camillo Boito’s brilliant career by emphasising ‘his dual manifestation as a writer and an artist, equal to those marvellous Renaissance artists who handled pencils, sticks, brushes or pens just as easily’. And again, we read of ‘his grandiose and vivid eloquence, so elegant and truly classical in form and profound in concepts, aided by his physical presence, the sonority of his voice and the breadth of his gesture’. Finally, with regard to the practice of architecture, Colombo cited ‘an even rarer quality, as his estimates were accurate and not overtaken by the final figures’.