What we want to tell you today is the intertwining of the history of the association of four polytechnic alumni and History, the one with a capital H.

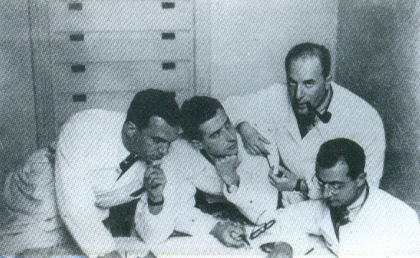

The year is 1932. Leafing through the yearbooks of that year’s graduates, we would find four names that later became fundamental for Italian architecture. They are Gian Luigi Banfi, Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Enrico Peressutti. The first three have been friends since high school, joining the first year of Peressutti University.

In July 1932 they graduated working on their thesis together. The approach is predominantly academic, consistent with the approach given to the school by Camillo Boito. Those rigid prescriptions immediately brought out the preferences of the four.

We could not reject the themes as a whole; however, we tried to at least free ourselves from stylistic constraints, approaching the design with a language taken from the first testimonies of the Modern Movement.

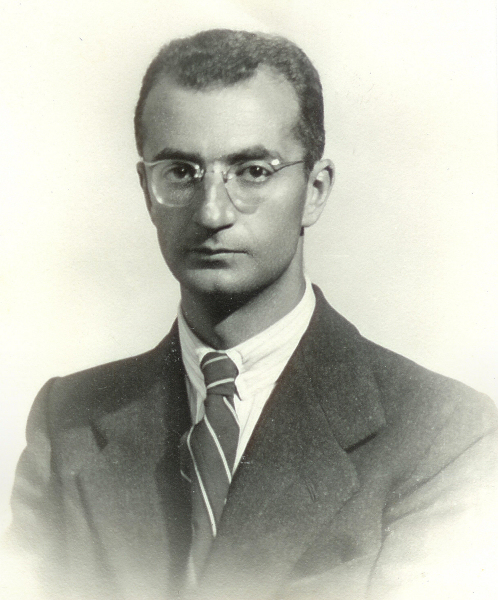

Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso

This is how Studio BBPR was born, from the initials of their surnames, in strict alphabetical order. The group immediately joined the struggle for the renewal of both national and international architectural culture, historically and critically deepening the contributions of the new operational concepts. Their “rationalism” appears to be meditated, avoiding falling into imitative and manneristic misunderstandings. In 1935 they became members of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM). They also began to collaborate with some magazines, including Quadrante and Casabella.

But let’s remember once again what years we are in, because it is impossible to consider the events of the group by separating them from the historical climate that Italy is experiencing.

In fact, if the rejection of the rhetoric and monumentalism of the fascist regime is clear, the stance with respect to the political structures that underlie it is not so clear. The “BBPR” seek to condition the regime from within, by means of a modern and progressive cultural praxis. The honesty of their intentions is demonstrated by all their theoretical and professional work.

The deterioration of the political situation and the war, however, marked the awakening from illusion. Between 1936 and 1940, all the members of the group moved from a position of faction within official fascism to one of militant anti-fascists.

Rogers began to question his adherence to the regime in 1937, on the basis of the reflection that the “architecture of human measure” could not coincide with fascism.

In 1938 the first racial laws were promulgated. Because of his Jewish origins, Rogers is forced to remain anonymous and can no longer sign projects and articles. Together with Belgiojoso he joined the anti-fascist movement Justice and Freedom, from 1942 the Action Party and in 1943, the National Liberation Committee. In the same year, the two were arrested for a few hours on charges of unauthorized propaganda activities. Rogers then decided to go into exile in Switzerland.

In 1943 Banfi also joined the Partito d’Azione and was one of the clandestine promoters of Italia Libera, until 8 September: after the armistice he tried to organize an armed resistance against the Germans in Chiavari. Back in Milan, he dealt with the clandestine press and the expatriation to Switzerland of groups of Jews, keeping in touch with the partisans of the Intelvi valley, where Banfi owned a villa that became an active center of resistance and sorting of fuorusciti.

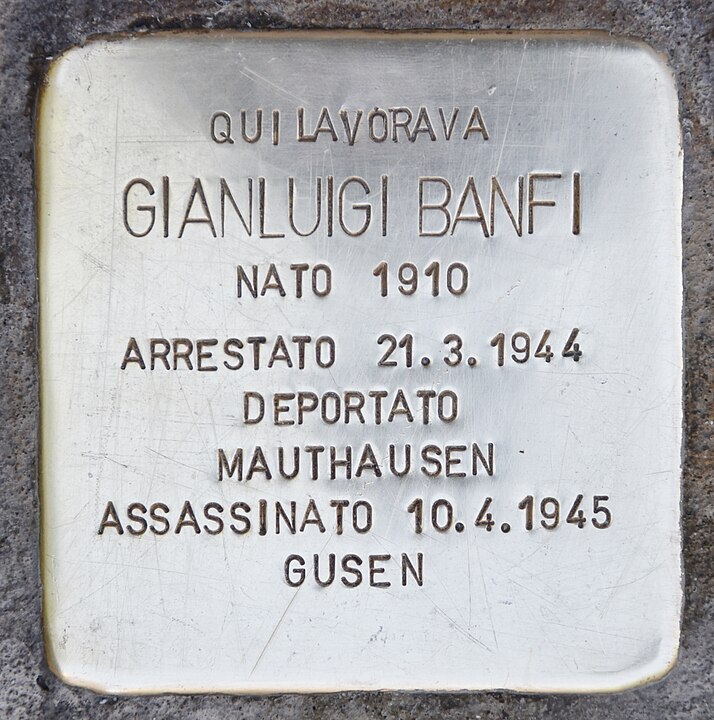

In 1944, following a tip-off, Banfi and Belgiojoso were arrested for espionage and conspiracy and detained in the San Vittore prison for 45 days, before being sentenced to deportation. For the next three months they were locked up in the Fossoli camp, and then transferred to Mauthausen-Gusen.

Belgiojoso remained here until 28 April 1945, when he moved to Gunskirchen. He was liberated by American troops on 4 May.

Banfi, on the other hand, had died at Mauthausen a few weeks earlier, on April 10, less than a month before the Germans surrendered.

After the war, the BBPR studio gained widespread recognition thanks to the professional, teaching and editorial activity of its three surviving members. Some of their works, including the post-rationalist and brutalist Torre Velasca in Milan, play an essential role in twentieth-century architecture.

From the 1980s onwards, Belgiojoso began to recall the experience of deportation in some writings, accompanied by drawings drawn up during his imprisonment and immediately after his release.

“The camp was just suffering. Suffering filled every space, like something solid. You could catch it in the slow rustle of those who moved dragging themselves, you could recognize it in your voice and gestures, you could transmit objects to places, to the landscape.

Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso

The architect will continue to remember those events through a series of commemorative works: the Monument to the Political and Racial Deportee at the Monumental Cemetery in Milan (1946, with the BBPR), the Memorial to Mauthausen-Gusen I (1967), the Monument to the Political and Racial Deportee in Carpi (1973), the Italian Memorial in the Auschwitz Camp (1979) and the Monument to the Deportee in Sesto San Giovanni (1998).

Today, passing in front of number 2 of Via dei Chiostri in Milan, headquarters of the BBPR studio from 1940 to 1998, you can come across the stumbling block that commemorates the deportation and death of Gian Luigi Banfi.