An app for mapping, enhancing and letting everyone from Milan and elsewhere discover the modern architecture of their city: this is Archimapping, an innovative application developed by Politecnico di Milano, funded by Fondazione di Comunità Milano and realised in collaboration with AIM. This app, available in both Italian and English, aims to highlight Milan’s contemporary architectural heritage, including the 100 most significant buildings from the Unification of Italy to the present day.

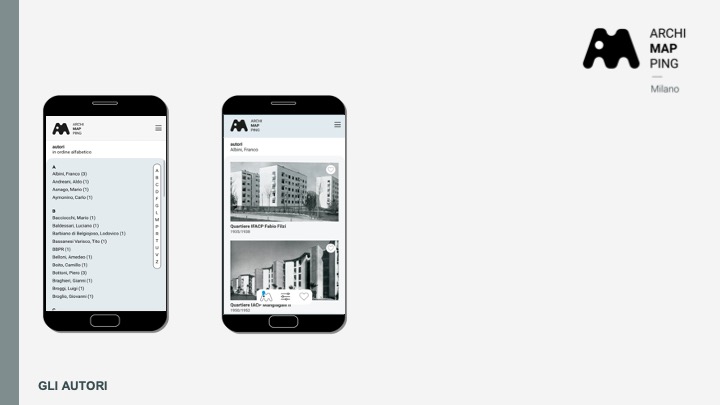

The app transforms Milan into a vast museum of contemporary architecture accessible to all. Equipped with geolocation, Archimapping suggests thematic routes and allows users to create customised itineraries based on typological, geographical, authorial and chronological criteria. The main objective is to promote knowledge of the area and architecture among citizens, students and tourists, encouraging recognition and identification of people in the places where they live.

Archimapping, selected works

The selected works narrate the history and evolution of Milan’s different districts in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, reflecting the social, economic and cultural dynamics of the city. Each building is presented through a concise description, historical or archive iconographic material, essential bibliographic references, links and video highlights. The Archimapping app is a valuable tool for the cultural promotion of the city, encouraging active participation in the care, protection and promotion of the urban environment.

Archimapping, Marco Biagi tells how it was born

Marco Biagi, architect and professor at the Department of Architecture, Construction Engineering and the Built Environment of Politecnico di Milano, together with late professor Federico Bucci and professor Carlo Berizzi, president of AIM (Associazione Interessi Metropolitani), is responsible for the research that led to the creation of the web app. He tells Frontiere how it all started.

“Archimapping was born from the need to map and make usable the modern architecture of Milan. I have been involved in the development itineraries and guided tours for a long time. In the mid-1990s, I collaborated with the Centre for Architecture of the City of Milan promoted by architect Titti Busacca and, later, with the Foundation of the Order of Architects. Over the years, however, I have noticed that when there are these initiatives, something is always missing: drawings, plans, various materials for both the interested public and also for insiders and students. Hence the idea came of using smartphones, GPS and geolocation to create a tool that would be didactic and at the same time informative and allow for a sort of census of modern architecture, especially buildings. The choice fell on buildings of recognised architectural value, with bibliography and journal articles. Milan is the capital of ‘modern’ in Italy and lends itself very well to this objective. Hence the idea came of gathering in a practical tool a whole range of information that could in some way accompany a possible visit. GPS can also help ordinary citizens, tourists and professionals ‘discover’ architecture. In this first version, we focused on Milan, but the idea is to replicate the mapping on the territory as well: for example, you find yourself somewhere in the countryside, you click on t he app and it points you out the significant architectural presences in the area their distance. I remember once I was on Lake Maggiore, above Luino. I knew there was a house by Carlo Mollino nearby but I didn’t know where exactly: the app would certainly have made it easier for me. Archimapping is meant to be a tool for knowledge, enrichment and enhancement of the territory as well”.

Why modern architecture only?

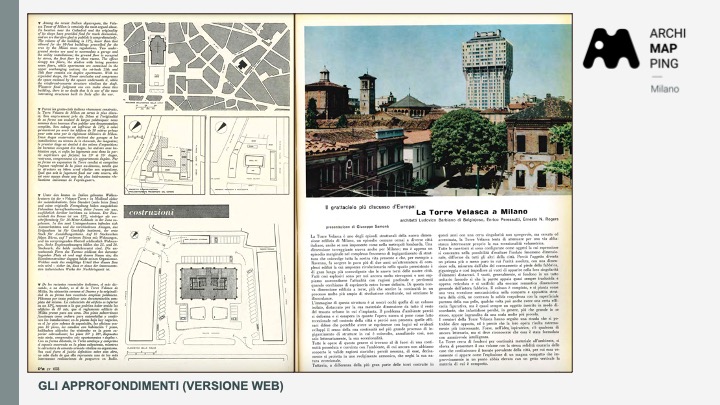

“We focused on it because we have publications, magazines and archive documents that are often forgotten.

With Professor Federico Bucci, who was also responsible for the libraries and archives at Politecnico, we thought of Archimapping as a way to retrieve and make usable materials that are usually difficult to access. Magazines, in particular, are designed for popularisation are therefore an excellent tool for talking about architecture to everyone, as in them, plans and texts are adapted for lay readers and often the texts are already bilingual.

One of the distinguishing features is precisely this being in the middle between popularisation and science: the datasheets are scientific, they are verified and endorsed by university professors, and are not limited to historical anecdotes”.

Is Archimapping a way for Politecnico di Milano to open up to the city as well?

“We hope to extend the range of actors involved. Milan is a city with many initiatives and many out-of-towners who want to discover the city.

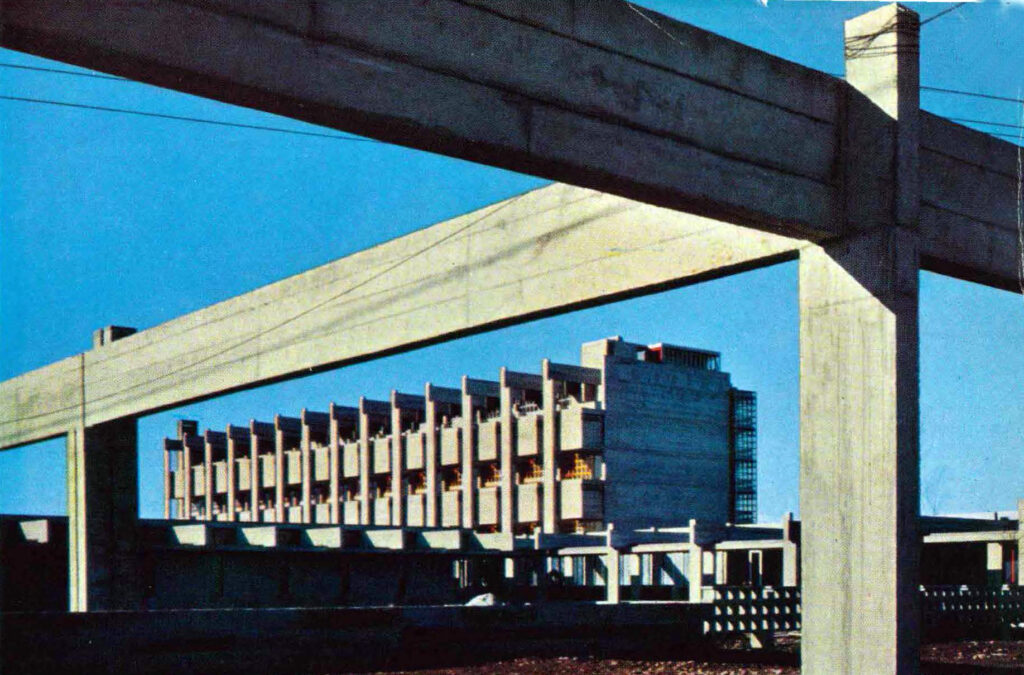

Fondazione di Comunità di Milano funded this project because the idea was also to promote knowledge of the city among citizens. We made sure to include in the map, in the selection, buildings from all the municipalities of Milan, not just the city. The aim is to make people discover and appreciate modern architecture, which is often viewed negatively. For example, Vittoriano Viganò’s Istituto Marchiondi is perceived as an abandoned eco-monster, a place of decay, but indeed, it is a masterpiece of modern architecture, featured in all the international magazines. In cases like this, mapping is the first step towards enhancement and recovery.

Certainly, the project is evolving; if we were to expand the work in Milan, the starting team would no longer be sufficient, we would have to involve other professors of architecture and history, designers… both within the School of Architecture and in the city (Municipality, Foundation of the Order of Architects, etc.), in short, to open up collaborations.

Is there a building that has particularly struck you?

“Milan has a tradition of social, cooperative and social housing, with even important examples of great quality that I am very fond of. One example is on the Navigli: Franco Marescotti’s ‘Grandi e Bertacchi’ social and cooperative centre, a self-funded housing complex built as a cooperative with a modern design in the post-war period. We are talking about council houses that were built at that time on the edge of the countryside with a social centre open to the neighbourhood with an adjoining hall where people danced, ate, had parties and meetings. These are fascinating places, even today.

I also love more well-known buildings, in the field of social housing again. I am thinking of Monte Amiata, a residential complex in the Gallaratese district, designed by Carlo Aymonino with several casa a ballatoio (flats sharing the same open gallery on each floor) designed by Aldo Rossi.

There are many guides to modern architecture in Milan, some of them recently published, but they often focus mainly on bourgeois architecture, by well-known architects such as Caccia Dominioni, Gardella, Albini… because it is the typical Milan’s style of the 1950s-1960s, which has set the standard worldwide. There are examples of architecture that are often overlooked: they are perhaps less ‘refined’ in terms of taste, but they have nevertheless improved urban life from a functional point of view, and provide us with very important information for reading architecture as an element in the evolution of the city.

The idea is to get students more involved as well, especially since today’s students have little experience of the library and lack the necessary tools to read Milan’s transformations in an indispensable historical perspective. The app could be a lure to make them curious and get them to return to books”.

Is Archimapping a model that can be replicated in other cities?

“Our first ambition would be to increase it first of all in Milan, but we do not exclude exporting it to other Italian cities and other territories, especially where there is clearly a presence of modern architecture. The highest aspiration would be to replicate the project in other European cities, perhaps by building a network of international universities through EU funding”.

Besides Archimapping, die you also worked on other similar projects?

“A similar mapping experience is the one developed in the 2021-22 academic year, with my first-year students, for the ‘Inventing Schools’ educational programme, organised by Politecnico in collaboration with the Municipality of Milan. The objective of this initiative, coordinated by Elvio Manganaro and Barbara Coppetti, was to work on a number of school buildings in Milan in order to point out critical issues and propose solutions to be funded with special funds from the National Recovery and Resilience Programme. A digital publication was also born from the project”.

Can we say that architecture has a civil value?

“I am very interested in reading architecture, not just as an object but as a part of the city that contributes to everyone’s life. If you don’t stop at the superficial details of a building and contextualise it, you begin to understand the dynamics of the city: who builds it, who designs it, who allows it to be designed… and this allows you to better understand how the quality of architecture changes over time.

Let me give you an example: for the February issue of ‘Casabella’, a magazine with which I have been collaborating for several years now, I covered the publication of the renovation of former Istituto Piero Pirelli, in Viale Fulvio Testi, which used to be a training school for the children of Pirelli’s workers, where their learnt the trade. It was built in the 1950s and designed by architect Roberto Menghi, and has just been redeveloped by Camillo Botticini and Matteo Facchinelli’s ARW architectural firm. The comparison between the architecture of Menghi, a typical professional from Milan of the time (he had worked with Gardella, Zanuso, Magistretti, Albini and Ponti) and the architects of the renovation also highlights the evolution of professionalism, culture and vision of the city.