When we think about augmented reality and virtual reality, we often bring to mind situations linked to the world of entertainment or specialised training. Thanks to the increasing availability of headsets and smartphones, these technologies are also taking hold in other environments, such as the virtual enjoyment of cultural heritage. What’s more, there are an increasing number of projects researching how these digital innovations can be also be used in social and daily life.

One of these projects is 5A – Autonomie per l’Autismo Attraverso realtà virtuale, realtà Aumentata e Agenti conversazionali (Autonomy for Autism through Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Conversational Agents), led by I3lab (Innovative, Interactive Interfaces Laboratory), based in the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering at the Politecnico di Milano, in collaboration with two prestigious care institutions – the Fondazione Sacra Famiglia Onlus and the Associazione La Nostra Famiglia – and funded by the Fondazione TIM.

The research involves the use of innovative interactive applications based on smartphones and wearable headsets which integrate Immersive Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Conversational Agents. The aim of the project is to enhance the autonomy of people (especially adolescents) with ASD (autism spectrum disorders) in order to foster social inclusion and improve their quality of life.

“The project is led as part of a call launched by the Fondazione TIM, but we had already explored this route in our laboratory, through Masters and PhD theses and various other research projects,” explains professor Franca Garzotto, lecturer in Information Processing Systems and Scientific Coordinator for 5A. “In fact, we already knew the two partners, the Fondazione Sacra Famiglia and the Associazione La Nostra Famiglia, because we had worked with them in other contexts in the past.

The 5A project really was established together with these two care partners, and one of the fundamental ideas behind this project came directly from them: using technology to address the issue of cognitive rigidity, mitigating the difficulties with generalisation often suffered by people with autism, and helping them to develop conceptualisation skills.

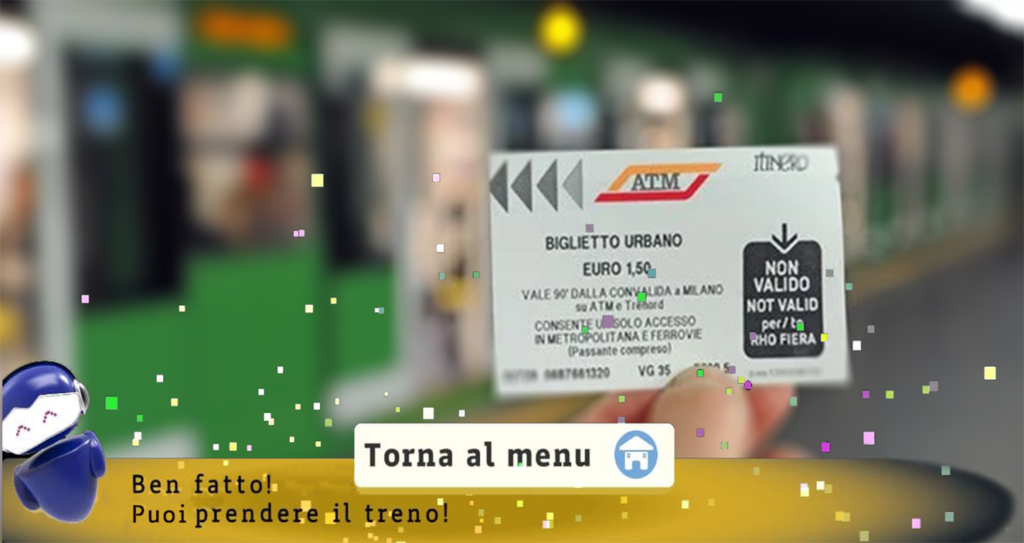

Given that the topic of the call was the development of autonomy for autism, we defined autonomy as the ability to be independent in the essential tasks of daily life, and we focused our efforts on mobility in urban spaces: the metro, trains, supermarkets, museums, libraries, hospitals, etc.

In previous research, virtual reality had already been used as a training support for people with cognitive difficulties. However, underlying problem is that, in the real world, the person does not encounter exactly the same scenario they experienced in the virtual world;therefore, they become disoriented precisely because they are incapable of generalising what they learned using the technology. How can we try to overcome this limitation? We had the idea that, after the virtual reality experience, in which the person experiences a simulation of certain tasks, once they are in the real world, they need something to connect them to their previous virtual experience in order to be stimulated into applying the skills learned and understand how to do so. This led to the idea of coordinating augmented reality with virtual reality through transmedia elements: these elements are common to both virtual reality and augmented reality, with the latter used to help the person when they are in the real world. Here, through his smartphone, the guy can see, superimposed onto his view of the world around him, certain visual elements from the scenario that had been simulated in virtual reality and, most importantly, he finds his “virtual companion”, a friendly and comical conversational agent who does not simply give instructions but is interactive, speaks and helps him to remember and generalise. This was clearly suggested by the therapists, and we have tried to achieve it in the best possible way, although we recognise the limitation of not being able to map exactly all real-world situations into virtual reality.

Will you also collect data that can be used to fine tune the technology?

“We will start to collect data soon, when we start experiments in the field at the two centres, the Fondazione Sacra Famiglia Onlus, based in Cesano Boscone (Milan) and the Associazione La Nostra Famiglia- IRCCS Medea, in Bosisio Parini (Lecco). We will engage a group of therapists and at least 60 teenagers with autism, who will be recruited by the therapists. We will collect data both automatically (recording all user interactions in virtual and augmented reality being in the cloud) and through observations, questionnaires and focus groups.

The data analysis will therefore be both qualitative and quantitative. We will have information on usability, satisfaction, and hopefully also on the effectiveness of our tools in relation to learning and capacity for autonomy, measuring several aspects before and after the training in virtual reality and before and after the experience in augmented reality.

Empirical assessment in the field of autism is always very difficult, because every person is profoundly different from the next, even when they have the same clinical profile. However, working in our favour there is also the fact that these people love interactive technology: it is seen as a game, it is not emotive, it doesn’t get tired when you stress it, it doesn’t lose its patience and it is predictable. And teenagers are digital natives anyway – using a computer or telephone comes very naturally.”

Did the therapists help you with the design?

“It was a true co-design effort with the therapists, through four workshops in which six therapists helped us design both the virtual and the augmented realities, often creatively, such as using transparencies over real photos of the city to see which elements should be superimposed. They also helped us in the conversational part, providing very interesting and accurate instructions on how to create appropriate dialogues for people with autism, both in terms of the flow and wording of the phrases used by the conversational agent, and in terms of the interpretation of the language they use. The therapists supervised us really very closely in all these processes.”

What is the final product that you hope to implement with 5A?

“The final objective is to create a virtual reality application integrated with an augmented reality application that allows people to be as autonomous as possible in typical situations of urban mobility, and hopefully, in the future, other everyday situations. A learning and support process that starts with training in the virtual world – to be done at home, school or at a therapy centre – and develops into a digital aid, contextualised in space and time through augmented reality, which helps the person in a specific time and place.

Do you think that this technology will be used in therapeutic contexts only, or will it become available to the masses?

“In reality, at the moment these are apps designed not for therapeutic purposes, but we believe that they could be adopted as an aid during more traditional therapies for autism. We would like to develop a mass-market technology that can be used by anyone. This is technically possible. Essentially, for both virtual reality and augmented reality, the apps can easily be downloaded and used on mid-range smartphones, which we will make freely available to anyon who wants to use them. However, the scenarios that we will manage to develop over these two years of the project are limited: designing and implementing a scenario is really very complex and laborious, especially because every single element has to be not only functional but also absolutely perfect in terms of interface and interaction, and suitable for people with autism. In addition, the technology is continuously evolving and we have to manage continuous software updates. So, there is a sustainability issue linked to the need to increase the number of scenarios and keep the applications going, and we need to find a way to finance the expansion and technical maintenance of the apps in the medium-long term. We are already working to find an operating solution for next year, when the project will come to an end. Fingers crossed!”