We met Kjetil Trædal Thorsen before his lecture at the Politecnico di Milano on the topic of “Nature as the client” in which he described his projects dedicated to architecture in vulnerable mountain landscapes, which was followed by the opening of the exhibition “Arctic Nordic Alpine” (open for free in the atrium of the School of Architecture until July 27). Its purpose is to investigate the impact that new constructions can have on these extreme geographical and climatic environments.

He is a sporty, tanned man who loves fishing and in speaking reveals a sincere concern for the legacy we will leave to young people and for the urgency to protect the most fragile landscapes.

THE MEETING

You were the young founder of the Snøhetta practice, an international practice of multidisciplinary architecture. Could you talk about your firm and explain how you started?

When you are very young, you have no limits, you think everything is possible. And for us it was extraordinary to win the competition for the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria, Egypt, which kind of catapulted our careers a little bit. But it also took a very long time, so we had to be very focused for almost 12 years, working almost exclusively on this project, even though we made some other, smaller projects in the meantime.

How old were you when you founded the practice?

I was 30, but I studied for a long time in Austria, in Graz, because at the time you didn’t feel the pressure to finish. But when I moved back to Oslo, to Norway, I couldn’t find anywhere to work so, with a small group of friends I met there, we decided to set up a small practice and see how it went.

It was 1987 and at the time we already knew it was going to take a lot of effort and a long time. We sketched out a thirty-year plan, a generational plan. We defined the first ten years as trying to establish ourselves, the next ten years to consolidate the multidisciplinary aspect of the profession and the ten years after to start building and trying to do important things.

And it almost went according to plan, but at the same time there were a lot of struggles and hiccups, the economic crisis in 2008. A lot of things didn’t go to plan, but you can’t plan for everything, right? A lot of semi-coincidental things happen when you win a competition like the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. The next big one we won was for the Oslo Opera House in 2000, but at least then we had proven to ourselves and others that we were not one-hit wonders.

So, to some extent it started establishing itself as a real practice and then slowly, organically, we expanded from landscape architecture and architecture to art, which we included very early on, to interior architecture, urbanism, graphic design, digital design and product design.

So, all of a sudden, we had all professions inside the company and now, after so many years, almost 35 years, we have practices in Adelaide, in Australia, in Hong Kong, Paris… And now things are moving forward really quickly.

How do you manage to maintain such a high level?

You have to be on fire, all the time, even if you get older. You cannot relax, you have to be really engaged, focused all the time. Because so many things happen within a split second, you have to be open-minded and breathe the air around you continuously.

You have to get inspired by things that you wouldn’t normally get inspired by. I think it is very important to have the capacity to combine seemingly unrelated issues. Like the right side of the brain and the left side of the brain have to find some sort of consensus, and then sometimes good ideas arrive.

Coming back to the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, which was followed by the Oslo Opera House and the National September 11 Memorial Museum in New York, how do you manage the responsibility of designing such iconic buildings?

It’s a responsibility that you take on very early and then you organise accordingly. So yes, it is a big responsibility to be doing these projects but you are not only relying on yourself, you have a collective, you have different professions that will contribute.

So, to some extent, you learn as you go. You establish certain procedures in the office to make sure you can control what is going on. You introduce some guidelines for the architects, for example, never using more than three materials for a detail.

But first of all, you have to hit the concept right. You have to be contextual and conceptual at the same time. Oslo is different to Tokyo. You cannot react in the same way with the architecture in an Arabic country as you can in Paris. They are all different. That’s why we established a coherent process where we put people first and then try to look at architecture as a tool to enhance the accessibility of public buildings.

Where is your body? Where is your horizon? How does that compare to nature? A lot of different points of view. Yes, and also the prepositions: in, under, over, in between, in front of and behind. All of a sudden, you understand that architecture provides a lot more possibilities than just inside and outside. Because today it’s all about nature as a client. Who do we listen to? Do we listen to the person or do we try to listen to nature?

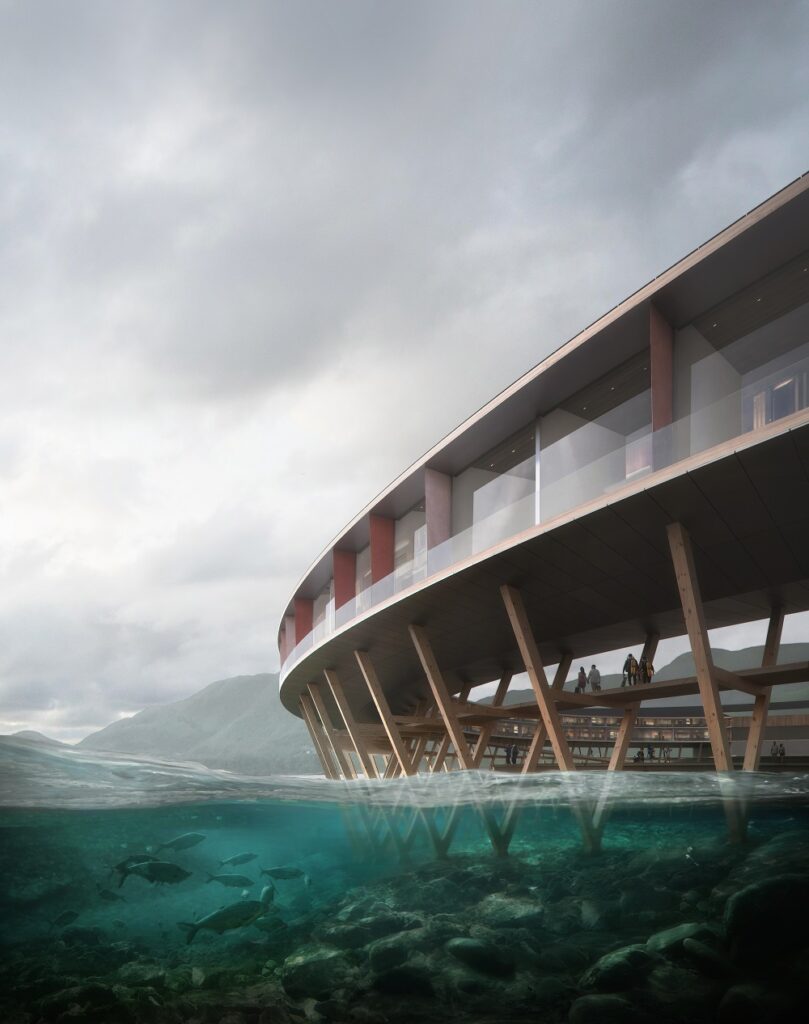

Yes, “Nature as a client” is the title of your lecture today at the Politecnico di Milano. You build large buildings in large cities but you are very careful of the fragile landscapes to which you have dedicated the exhibition being opened today. Why?

Simply because we are in a situation where a lot of nature is under stress, biological diversity is stressed, the climactic conditions are being stressed. We’ve been doing this for a very long time now, from the very beginning. We felt that it was important to show the students that. Even though it’s only a little portion of the work that we are doing worldwide.

For me it is a very important a personal language, that is trying to capture this understanding of vulnerable situations and protecting nature from humans. And these projects try to do that, whether it’s a factory or a visitor centre or a footpath.

Even the name that you chose for your practice, Snøhetta, recalls a natural landscape and it is in fact a mountain in Norway, in the municipality of Dovre.

Yes, but actually the story is slightly different because in Oslo there is a pub. We established the practice over that place and we took the name from there.

Your sensitivity to the theme of sustainability combined with greenery in outdoor spaces is well-known. Could you talk in particular about the use of wood and natural materials?

Yes, right now, of course there is no question and wood has always been a big part of the Nordic building tradition, mainly in residential buildings, but also in the construction of larger buildings. Trying to bring wood into larger urban scales, trying to turn it into a reasonable material for building bigger structures is still an ongoing fight because fire regulations worldwide are very strict.

But it is one of the better options for sustainable materials that we have today. It’s not ideal because for every cubic metre used in a construction, you should actually be planting three new trees. And keeping that balance is not easy, but it remains a better choice than many other materials.

We are fighting mainly against concrete, with the building industry emitting 40% of gases into the atmosphere; worse than flying and car driving put together. The building industry is a big “sinner” in that sense and we have to change that, looking at alternatives in the future and doing serious research. We know that we won’t get rid of the concrete, so we have to make it more environmentally friendly.

How do you manage to pass on your philosophy of sustainability in countries that are not as sensitive to this issue?

It’s not so easy. It’s more an evolutionary part of the job. We’re moving forward step by step, by encouraging for instance cleaner energy production lines, photovoltaic production which is efficient, the selection of recyclable materials.

In China or the Middle East it is moving but all of this is going too slowly and that’s why we have to focus on the issues of biodiversity in parallel, we have to find solutions quickly because there isn’t much time.

We know that your practice has also won the project for the Masterplan of the Ex Macello. Could you tell us about that?

That is a C40 “Reinventing cities” project in which we are trying to establish a sustainable direction on all levels, including energy production, transportation, the permeability of the ground, reducing the consumption of energy, clean energy production lines and renewable electricity.

So, there sustainability is part of the core of the project. But also reusing old buildings is a part of this. Because the CO2 is already accounted for in buildings that have already been constructed. The CO2 is already up there and that might be a problem. The Ex Macello is trying to be an example of how to work on several levels.

So, will you spend more time in Milan?

Yes, even if we have great Italians in the office who speak the language, whereas I always need things translated. But yes, I will definitely come more often.

Do you like Milan?

I love Milan. It’s a very diverse city and I like diversity. It has great educational facilities like the Politecnico di Milano, but it’s also a city where you feel it’s real. It’s not Venice, it’s a real city. It has industry, it has production lines, it has real people living here: it’s not a city for tourists.