We had the opportunity to meet Carlos Moreno when he was in Milan to attend the event CHANGE Tecnologia e creatività per uno sviluppo sostenibile for the presentation of our University’s first Strategic Sustainability Plan

Colombian-born Carlos Moreno is a professor at the IAE – Sorbonne University of Paris and co-founder and Scientific Director of the ‘Entrepreneurship Territory Innovation’ (ETI) laboratory. He is internationally known for his pioneering work on sustainable cities. In Paris, he worked to realise the model of the 15-minute city in which all services in the neighbourhood are within easy reach, focusing on reducing commuting by car in favour of walking and cycling to combat climate change, encourage the development of local economic activities and redevelop public spaces with a view to people instead of cars.

Professor, you are by now known as the inventor of the 15-minute city concept. What studies did you do and which people inspired your research?

Let me tell you that I am neither an urban planner nor an architect, although I have won several prizes in architecture. In fact, it has become my main activity in the urban field, but I stem from the world of mathematics and computer science. I actually have a degree and a major in mathematics, computer science and robotics. Therefore, I come from the world of technology and have applied technology in various fields – in particular to the city. I was one of the pioneers of what we call the smart city after the arrival of the Internet in the 2000s: it was an attempt to use technology and silicon algorithms to make the city smarter by managing traffic, services, infrastructure. I worked a lot in this area until 2010. And in that year I really changed, I stopped working on the technological smart city because I met inspiring people who have always accompanied me. Edgar Morin is a world-renowned French philosopher and sociologist, who is now 102 years old and still alive. He is highly regarded in Italy as well and has developed what we call complexity science, which concerns the management of interdependent situations and systems. I have read a lot of Edgar Morin, who has inspired me enormously to leave technology as the main vector and helped me understand that the city is a very complex system with many interdependencies and that the main challenges are climate, wealth, poverty, economy and social life. So, I can say Edgar Morin has been one of my mentors. Then, in 2010 I read a book by Muhammad Yunus, winner of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. The title is: ‘A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions’ and this fitted perfectly with my way of thinking. They have both inspired me a lot and I am friends with both of them. Oh, and I shall not forget Saskia Sassen! She was born in the Netherlands and raised in Argentina, she works at Columbia University in New York and now lives in London. She is a citizen of the world and was the first to develop the concept of ‘global city’. She has been a big inspiration for me and I have worked a lot on this concept. As far as cities are concerned, I have been truly inspired by the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, as she has been a pioneer in urban climate policies and foreseen climate challenges before many others have. She has been a leader of the C40, the global network of cities for climate. Thanks to her, I could work with other cities to make these concepts global.

And when did you start your research on the city as such?

I started in 2006, moving from the world of technology to the city and spent a lot of time exploring how to improve urban life, the quality of life in cities. In 2010 I realised that the biggest threat was climate change and that we had to anticipate it. We had to offer a different lifestyle, one that was not based on dependence on cars and fossil fuels. In 2015, the COP21, the major world climate conference where the climate agreement was signed, was held in Paris. I argued that we should not only consider states, but also cities. So in 2016 I proposed the concept of a ’15-minute neighbourhood city’ to say that we need to fight climate change and reduce the need for forced commuting, have more proximity, more local jobs, more public spaces, more services. So it was in 2016 that I made this concept public.

How did you collaborate with Mayor Anne Hidalgo in Paris? And what results did you achieve there?

At the C40 I realised that Anne Hidalgo was really a pioneering woman, because she made climate decisions for Paris when it was not that popular to. I met Anne Hidalgo and let me tell you, we share some cultural affinities. She was born in Cadiz, Spain, and arrived in Lyon when she was very young; I was born in Colombia, South America, so we share some cultural affinities. We know what it means to arrive at a young age in a foreign country. We are part of those who have roots elsewhere but live in France. She is a very determined and courageous person… and I too have my convictions.

So it was a meeting between a politician and a researcher?

Yes, she wanted to change her city and I wanted my concept to be implemented in Paris. The researcher cannot produce political change, whereas the politician, who relies on science, can. So in 2016 I told her: ‘Look, I have this concept called “the 15-minute city”. If you wanted, we could do it in Paris’. She understood and gave me three neighbourhoods to experiment with my team and the municipality supported me: after three years, in 2019 Hidalgo told me: ‘I really like your concept, I want to take it and make it the core of my re-election campaign’. Then came Covid, which gave a strong boost to this concept worldwide, and Anne Hidalgo continued to develop it in Paris.

So, how was it implemented in Paris? What were the practical measures?

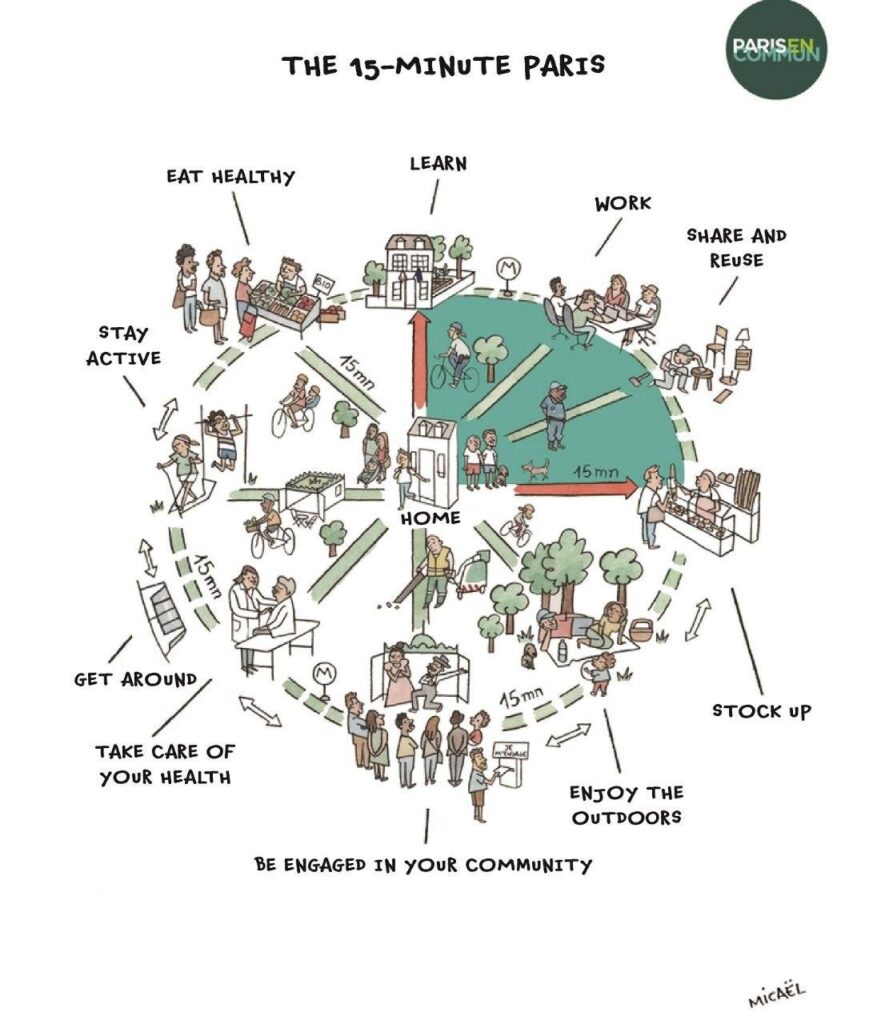

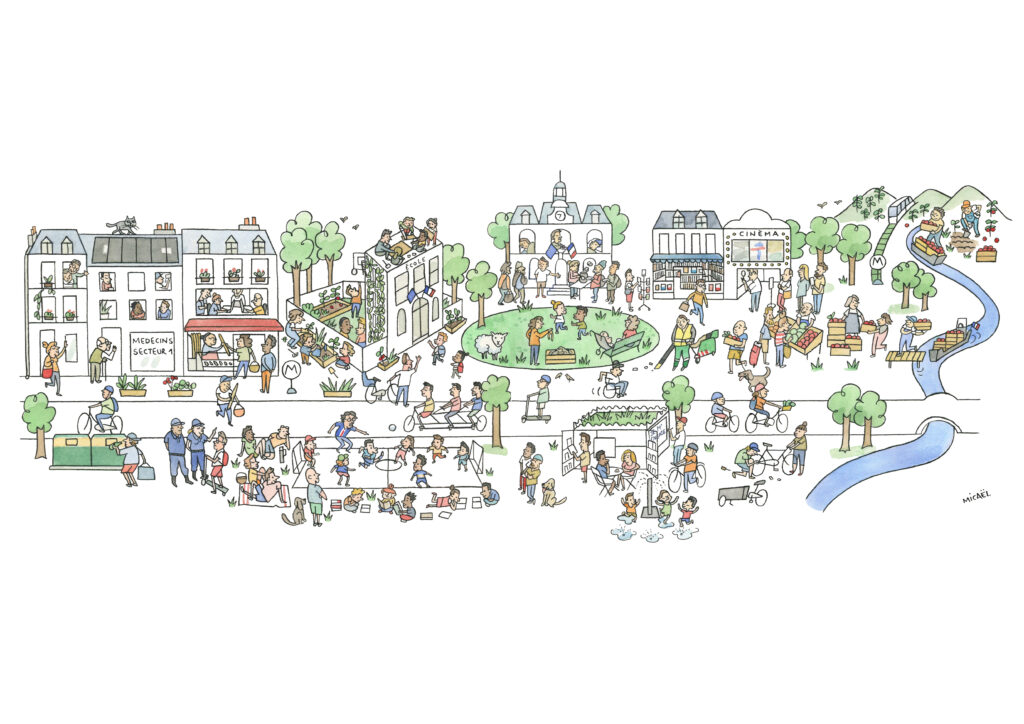

The 15-minute city is very simple and very practical. It’s about having everything you need within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from your home, work, schools, hospitals, sports, culture. We started by changing the use of the streets, reduced the presence of private cars, introduced the concept of ’30 zones’ and increased the number of bicycle lanes. We now have more than 1,000 kilometres of bicycle lanes in Paris. The priority is the redevelopment of public spaces, squares, gardens. We have reduced the presence of private cars, traffic has decreased, air quality has greatly improved and noise in the streets has also decreased. We increased the number of local jobs and developed neighbourhood businesses. We were able to guarantee services to residents. Jobs, schools, health care services were brought back to the neighbourhood. We have many public space buildings opened to the public. So people can go out and exercise, meet others. It is really about offering more happiness and a better life. It is very interesting, and I think it can be an example for many other cities around the world.

And in which other cities has it been realised?

During the Covid period, the second city to embrace this concept was Milan with Mayor Giuseppe Sala, who included it in his re-election campaign. Sala is part of the C40, as is the mayor of Buenos Aires, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, who has adopted the concept for his city. The C40 created a task force and adopted the concept in July 2020, right during Covid, involving many cities: Montréal, Buenos Aires, Gatineau, Bogota, Seattle in the United States, Melbourne in Australia, Seoul in South Korea. Not only large cities, but also medium-sized towns, such as in Africa, Tunisia or regions like Scotland, which used to be a nation, or very small towns with 15,000 inhabitants, such as in Poland, or small rural towns with 5,000 inhabitants in France, such as Saint-Hilaire-de-Brethmas. My team at the Sorbonne University, together with the C40 and UN-Habitat, created the Global Observatory of Sustainable Proximities. Here, we brought together all the mayors in the world who are implementing this concept; to date we have 293 cities in the world implementing it.

But it can be applied in any city. Are there any exceptions? How is it possible to transform an existing city into a 15-minute city?

This concept, especially for existing cities, holds something very original that is rare to find in the world of town planning, because it does not depend on either size or density. We have the 15-minute city for the most dense areas and the 30-minute territory for the moderately dense or very sparsely dense areas such as the countryside. This concept seeks to create plurality of services, local economies, more service activities, more health services, more education. So, today we apply this concept in very big cities like Paris, Buenos Aires, Seoul in very different contexts. And this at the level of the whole city, because we try to change the policy at the city level, we try to vote on what we call local urban plans, ie 5, 10, 15-year city policy, as was done in Paris, Buenos Aires and then in many medium and small cities. What we want, for example, is to restore services that have disappeared. Many small towns have lost commerce, which has moved to shopping malls 30 km away, so we try to reintegrate neighbourhood commerce, create local jobs, reduce places crossed by cars to make room for inhabitants, have cultural and educational activities, medical services. There are no limits to applying it in very different contexts.

Speaking of mobility, how can we work and how can we convince citizens of the need to change their means of transport?

For 70 years, we have been used to things becoming normal for us. We are used to commuting every day at least two or three hours to work. We have become dependent on certain types of mobility such as the individual vehicle, which we use even for short trips. If we look at the statistics, we see that more than half of all car trips involve very short distances of less than 5 km. This is insane, not sustainable at all. We have become addicted to the car, as we consider it a social status, that having a car means being rich and walking or cycling or using public transport means being poor. We need to change the mindset: mobility is not an object, it is not the car. Mobility is a service, it is a service like any other, like going shopping or to the doctor, to school… mobility must be a service, not a technical object. So, just as there has been an automotive industry since 1914 in the United States, thanks to Mr Ford, cities organised themselves for cars and the car went hand in hand with the growth of skyscrapers, of motorways. It is considered a symbol of masculinity. We have created cities in the service of the car and have beocme centaurs-citizens who are half-man, half-car. And as soon as we touch upon cars, people argue that we are attacking their freedom, even though cars are hardly used and spend more time parked than in use. Public space must therefore be rebalanced, mobility is also public transport, mobility is also walking, cycling actions that must be protected with protected routes. Cars must have their place, but nothing more. We are not against the car tout court, but against the addiction and massive, unbalanced use of it in relation to the way of life in the city. Mobility today must be chosen, not forced. So we aim for a city that is organised in a polycentric manner with multifunctional places. The 15-minute city is the answer to climate change. We calculated that if everyone adopted this concept, we would reduce CO2 emissions, pollution and traffic congestion by 70%.

Drawing of the 15 minute city-Credit Micael_Fresque

Now that you are in Milan, what do you think about it and what would you like to change?

Milan is one of the European cities that are car-dependent and has pioneered the introduction of a toll to enter the centre; however, public transport, cycle paths and above all neighbourhood services must be developed: neighbourhoods must be created, with many activities. I walked with my wife from the Duomo to Bovisa and I noticed that as long as you stayed in the central area from the Duomo towards Parco Sempione, the Arco della Pace, Chinatown there were many services, but then beyond that the services became rarer and there was not so much public space. So you really have to create them, I think that is the key. In Paris it works very well because you really try to have services everywhere. The municipality itself has set up a property management company to rent premises at low cost to traders so that they can set up shops and accompany them so that they do not sell products from China, but local products, a political action to stimulate the local economy in a virtuous short circuit.

Last question: what would you recommend to a young person wishing to embark on a path like yours?

I often say this to the young people I am fortunate enough to meet, particularly at university. I say as a first thing that one must be curious. Never accept any truth as a revelation. Curiosity must be accompanied by questioning, which is why one must always verify what is objectively and scientifically true, otherwise one comes across many errors, lies and fake news. On social media in particular, many falsehoods are being told, denying climate change, Covid, vaccines. There is an extremely tough populist universe. And so young people must be careful, because a lie repeated a thousand times on social media cannot become a truth.

And then one must engage in fundamental battles that give dignity to the human being. We must fight for fundamental human rights that we risk losing today, such as the right to housing, education, health care, nature, biodiversity, water, air. We must fight to take back living spaces that are true living spaces.