There are many ways in which technology can support the world of health and wellbeing. Offering innovative and, above all, concrete solutions that simplify and improve the lives of patients and family and clinical caregivers is surely one of them.

At the Politecnico di Milano, we have a research group studying precisely this aspect, designing systems, products, environments and services with a human-centred and synergic outlook. TEDH – Technology and Design for Healthcare – is based at the Milan Bovisa and Lecco Campuses. It hosts the LYPHE laboratory, which applies technologies for studying users’ physical interaction with systems and ergonomics, and Sensibilab, which designs sensors for the wearable and non-intrusive monitoring of physical and physiological parameters with applications in the fields of medicine, sport and Assistive Technology.

By definition, the individual is the focal point of research conducted in this field, so the human factor – the specific needs of individuals – cannot be ignored. We discussed the importance of this type of approach with the youngest researchers at TEDH, Maria Terraroli and Martina Scagnoli, who told us how design, technology and human beings converge in their research.

The TEDH group’s research is principally conducted in the medical/rehabilitation fields; which projects have you been most involved in?

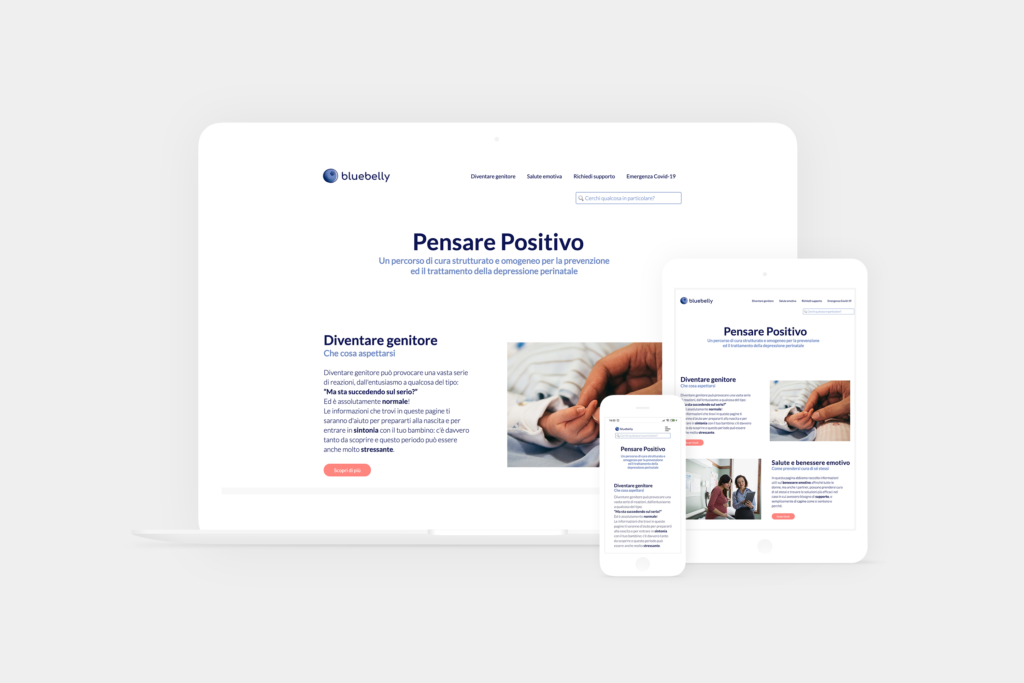

MT: The project to which I am most closely linked is Bluebelly, an application for administering and collecting self-assessment EPDS questionnaires on the user’s emotional state during the perinatal period, from the seventh month of gestation to the week after the birth.

The project was born in partnership with the Lecco Hospital, and has the important function of keeping mothers and pregnant women in contact with professionals from the gynaecological and obstetrics sector. As a research group, we have followed all phases of the project; from user research conducted through focus groups mediated by the hospital and consultants, to the development and testing phases. At the moment, the app is being tested within the catchment area of the Lecco ASST local healthcare agency.

MS: With the Multimodal Wearable -TUTA project, funded by a grant from INAIL, the Italian National Institute for Insurance against Accidents at Work, we created a system of wearable devices that monitor vital parameters (such as heartbeat and breathing) and the physical exercises performed during rehabilitation courses for returning to work.A suit is fitted with sensors and connected to an application that can be downloaded onto a smartphone, which supports the patient in rehabilitation activities performed remotely by quantifying the exercise through relevant indices that can be sent to the doctor.

Thus, the TUTA project both facilitates and adds to the recovery process. However, the fact that the patient is alone, without a professional present, is certainly a factor to be taken into account in the design…

MS: The patient is on their own, and is in a fragile mental and physical state, but the system motivates them towards recovery with its intuitive interface and ease of use, so the patient is encouraged to wear it and use it for guided exercise and a process involving quantitative indices that encourage the patient to follow the therapy without causing frustration.In the design, we in fact aimed to reconcile the aesthetic aspect with the functional one.

MT also worked on the TUTA project: what is the biggest challenge that you have had to face?

MT: One of the most problematic aspects that are often encountered in this kind of design is that of finding effective and user-friendly solutions for securing wearable devices to fabric.In this case, we used 3D printing technology to study morphology and create pre-series of cases and hooks for securing electronic devices to fabric.

Therefore, we could say that the work you are doing is to find innovative solutions that meet various needs. In this regard, how did you become involved in the world of design?

MS: My career did not start with design, but engineering, and specifically energy engineering. I have always had a passion for the sciences; but over the years I realised that although I like science and numbers, they were too limited in relation to my interests and passions, which also take in the artistic and philosophical fields.Therefore, I decided to apply myself to something that isn’t too sector-specific and technical. In design, I effectively found a synthesis of my interests, and the opportunity to explore them in a less vertical and more horizontal direction.

I therefore completed a three-year degree in Industrial and Environmental Design in the Marche region, where I am from; then I went to the Netherlands as an Erasmus foreign student at TU Delft, where I completed a laboratory internship on a project involving the use of scrap materials to create new products. This experience was very important for me, to the extent that when I returned to Italy I decided to enrol on Design & Engineering at the Politecnico. This programme immediately seemed perfect to me, because the combination of engineering and design brought together my passions for the sciences and creativity.

MT: My entire university career has been here at the Politecnico.In particular, I studied Product Design and was inspired by the course taught by professor Andreoni, who coordinates TEDH. When it came to choosing the topic for my thesis, I knew that I would like to work on a project with him, something that could solve a concrete problem.

Like Martina, who did her thesis on the TUTA project in partnership with INAIL, I also did a thesis on a TEDH project in partnership with a company. The project was for a smart glove, in which a reader that uses RFID technology (the same that is used in electronic cards, such as those used to pay for public transport) is directly incorporated into the conductive fabric of the glove. The product is currently still in the testing phase.

Have you participated in any other interesting projects?

MS: Of course. The European NESTORE project, aimed a elderly people with the objective of supporting a healthy lifestyle in an innovative and personalised manner, increasing the user’s functional autonomy.

MT: Technically, this is possible thanks to the use of several objects: a speaker, a bracelet and an analogue system, to monitor and visualise improvements in the exercises performed. Users therefore have a virtual coach device to guide and monitor the difference between the start and the end of the programme.

How would you define the human-centred approach that use adopt in your research?

MS: This type of approach starts with studying human beings in whatever context they find themselves; this means analysing not only physical needs, but also less obvious needs; investigating their emotional state, for example.It is an innovative approach because, in the past, research mainly focussed on the functional and medical aspects.

MT: Research and analysis are the initial phases, but they are also the fundamental phases in projects aimed at designing the right thing.For example, in the case of the Bluebelly project, we conducted three focus groups not only with pregnant women and mothers, who are the direct users of the application, but also with obstetrics professionals and psychologists, seeking to cover the whole spectrum of users.

Having a human centred approach therefore means taking account of the users’ ideas, expectations and suggestions.A similar process was also followed for the TUTA project, in collaboration with the Villa Beretta rehabilitation centre.

In your work, collaboration with doctors, physiotherapists and healthcare professionals in general seems very important. How has that collaboration been going? Is there confidence in the technology or have you encountered scepticism?

MT: In terms of my experience, linked to the development of the Bluebelly app, there is a lot of confidence. They informed us of the essential features required for the device to be developed and the related medical constraints; besides that, they gave us carte blanche. It has been nice to see the work of all designers be valued.

I imagine that there are also challenges to overcome when conducting such ambitious projects…

MS: The testing phase is essential: the more futuristic the design, the greater the need to test it, to ensure that it is safe. The obsolescence of devices not only reduces the obtainable quality, but inhibits new services and cost reduction; from this point of view, surely there is a need to finance a generational change in products and equipment.

In your opinion, what are the main developments in this field?

MT: We are just at the start of what these technologies can develop in the health sector. Of course, there is currently a lot of attention on issues linked to health and prevention.

For example, as TEDH we have advised CAPSULA, a company that makes a pod in which various physical and physiological parameters can be measured, thus returning a picture of the user’s health. It is an interesting project because it can be placed in environments outside of the sector, such as shopping centres. What we designers must focus our efforts on is making these technologies usable and as honest as possible…

MS: …and also understandable! The way in which information is conveyed to the user is fundamental. User experience and user interaction must therefore be central to the design, which must also take account of the target user’s knowledge, as well as the condition that they are in.

Technologies like 3D printing are making increasing amounts of headway in several fields. Will they be the future of medicine?

MS: 3D printing is very useful in environments in which there is a need to personalise a product, and medicine is certainly one of those. In fact, every person is different and has unique features. Until a few years ago, we had only discovered solutions which, following the logic of industrialisation, were produced en masse and the same for everyone. However, with 3D printing it is possible to obtain personalised solutions and design for uniqueness, not diversity, all at a relatively low cost.

MT: If some techniques can be more democratised and standardised, then obviously they would become more widespread. Looking to the future, we will surely arrive at a point where all hospitals will be equipped with 3D printers. At present, the number of small laboratories within hospitals is increasing, especially abroad, but the hope is that this process, to which design can make major contributions, will also accelerate in Italy.