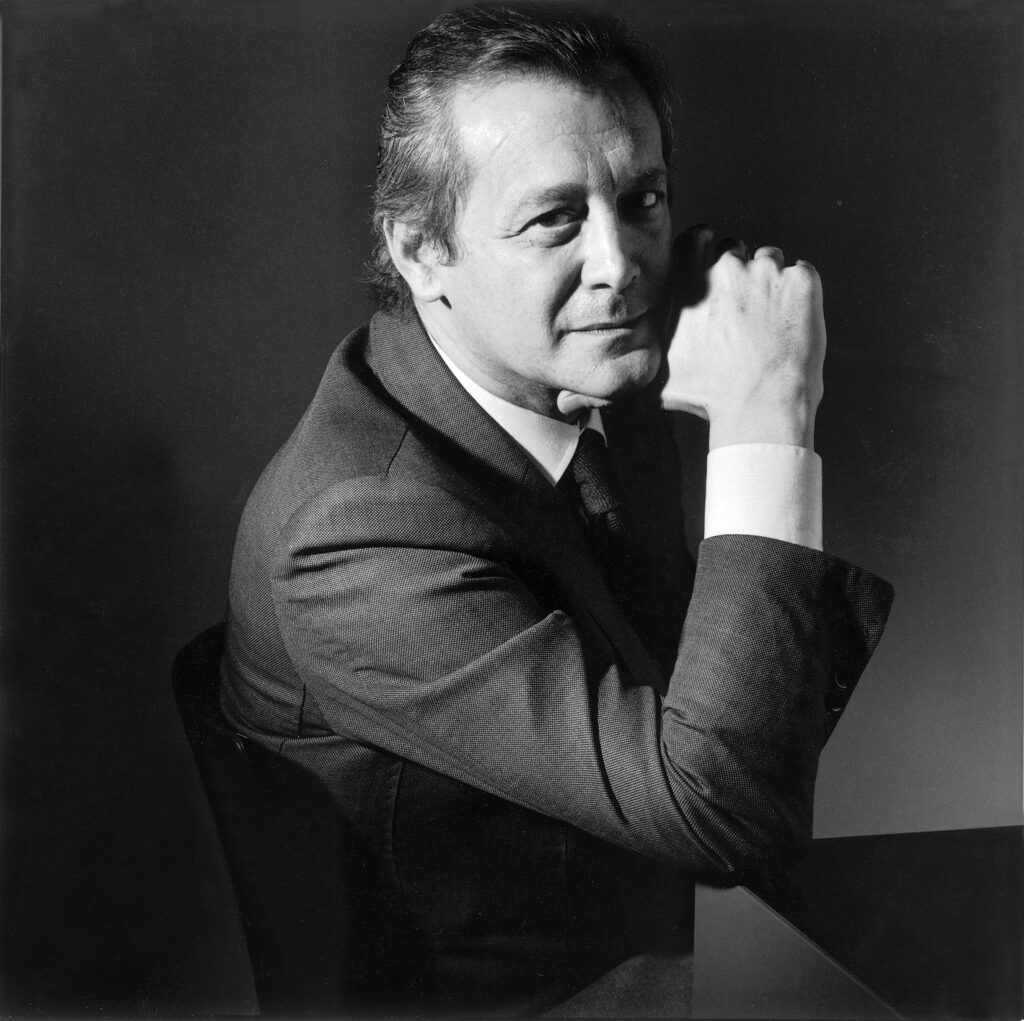

On the occasion of the opening of the Pierluigi Cerri exhibition titled Pierluigi Cerri. Furniture. Ideas, forms, intentions, on display in the Politecnico di Milano’s Historical Archives on the Bovisa Campus until 28 September, we met our alumnus and discussed his architectural thinking and multidisciplinarity.

Although his work is carried out in both national and international contexts, it is closely linked to Milanese reality. In fact, Milan is home to his studios in which he conceives the countless architectural and graphic design projects that punctuate his career: first, the Gregotti Associati studio, of which he is a founding member (1974-1998), then Studio Cerri & Associati (1998-2018), and now Pierluigi Cerri Studio.

You graduated in architecture from the Politecnico – what drove you to choose this profession?

I enrolled on architecture because I am somewhat seduced by the peculiarities linked to the work of an architect. I had the good fortune of knowing and collaborating with Rogers, Peressutti and Belgioioso from a very early age, observing the strong social commitment that was mirrored in every aspect of their work, and I found myself in front of something new, unusual. Until then, I had never considered architecture as something that improves people’s quality of life, but rather as the fruits of a work of art like any other, decontextualised… That’s it: that type of life, that way of approaching projects has seduced me ever since I was a boy!

From architect to graphic designer, how has your illustrious career evolved? How have these two areas intertwined in your design research?

This is a topic that I like very much: naturally working in two different disciplines, or even three sometimes, demonstrates my “eclectic” nature and therefore detesting specialists, with specialists understood to be those who voluntarily reduce their field of vision.

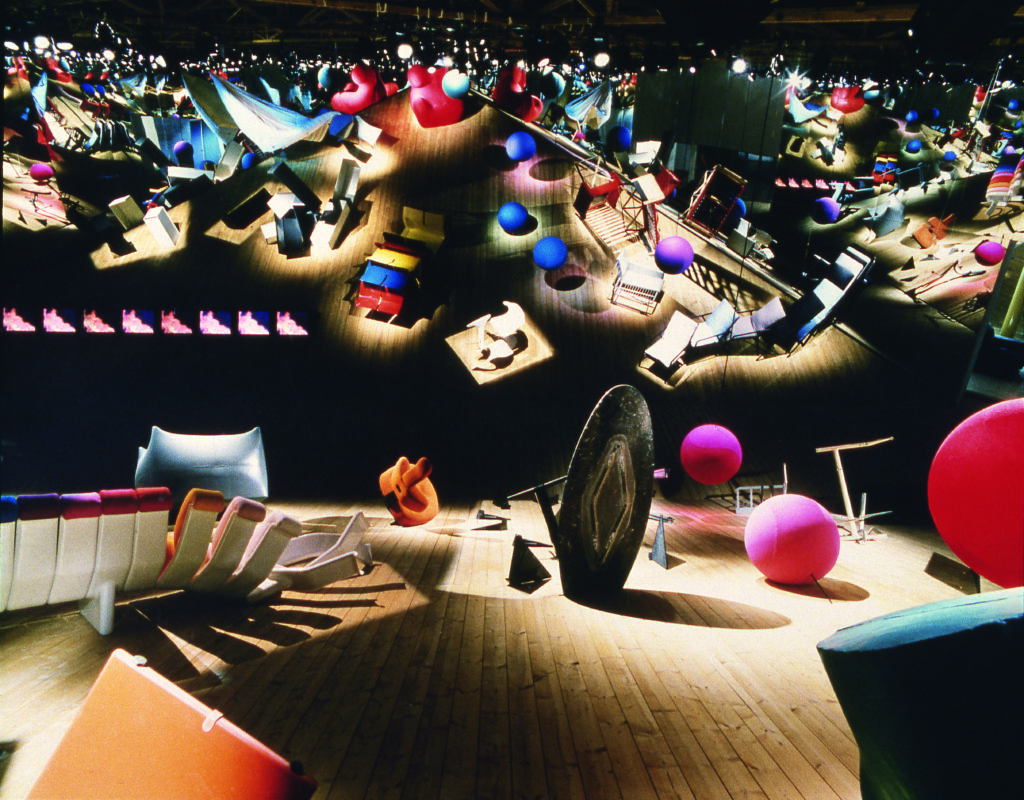

You have also worked on exhibition, interior design and ship design; what is the architect’s point of view when dealing with such diverse areas?

It is typical of architecture to look at various different fields. To create any kind of architectural design, whether it is a ship, a hospital or a technical building, you need to study. Study to understand what it’s all about. Naturally, designing a ship means tackling a number of problems that don’t exist on wet construction sites, but do in dry shipyards. It is no coincidence that ship design was one of the elements invoked by Le Corbusier in Vers une architecture, because ships are designed in millimetres, with all the resulting consequences, and designing a ship means designing a veritable horizontal building.

In the case of residential building, in my opinion its future should primarily involve city design: an isolated and decontextualised architecture makes no sense, and only becomes meaningful when the urban fabric is designed to accept it. There is one very good example: for me, the most beautiful area of Milan is the Foro Bonaparte. If you look at the individual buildings one by one, they are nothing extraordinary, but what makes the Foro Bonaparte an architectural masterpiece is its urban design.

Do you have a design to which you are particularly attached? Which one, and why?

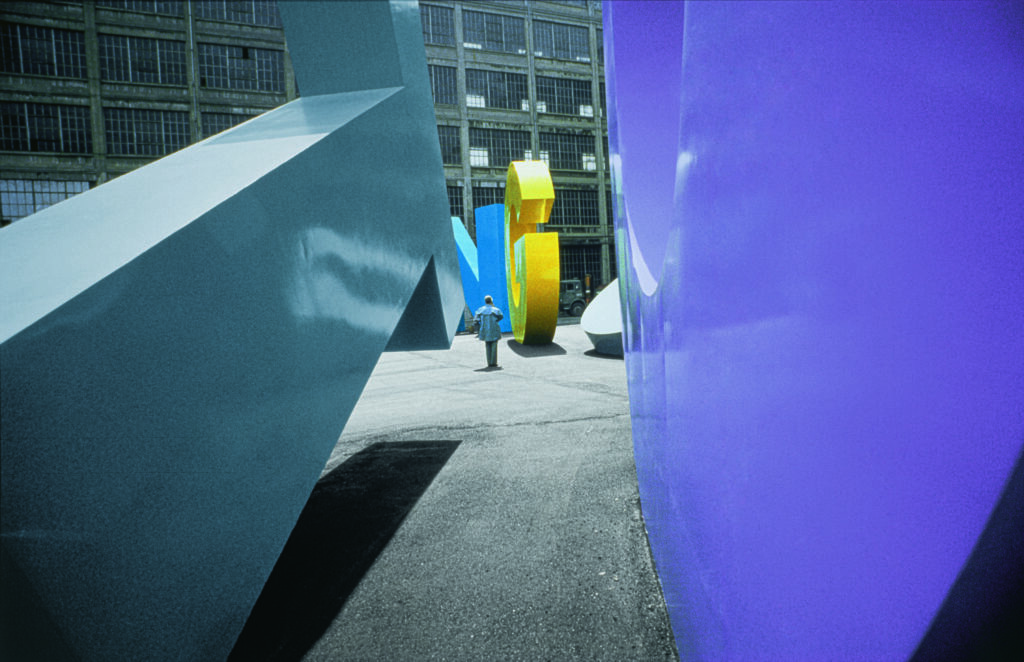

Certainly the Milan headquarters of Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, which is a project that seems to have been built on its original site, the former Riva-Calzoni mechanics’ workshop. In reality, the factory was completely modified, taking account of the materials and language with which it was conceived and some new services that it was required to host, that is, allowing for a three-dimensional view of the work, showing it from several perspectives on a journey along which the optics of how we perceive objects can change.

Speaking of exhibitions, you have put on several exhibitions in which particular attention is paid to the visitors. What is needed to involve the visitor in the exhibition?

There are a number of mechanisms. Firstly, the work on display needs to be placed at the centre of attention, in a predominantly silent environment. Then, the sequence of works must be one of the many possible stories and, finally, you need to ensure that a space that is able to express all of this emerges from the design. Ultimately the idea of the silent void comes from art, it comes from Enrico Castellani [contemporary Italian artist], Sol LeWitt and others.

Silence can become a building block and stylistic element of architecture.

What is beauty to you?

If you ask anyone in the street if that piece of architecture is beautiful or ugly, they wouldn’t know how to respond. Most people who move around the city, generally with their heads down, struggle to find a way to define whether architecture is beautiful or ugly, to say why they like it or don’t like it.

In general, saying whether a piece of architecture is beautiful or ugly is very difficult because the judgment is linked to a number of elements and relationships, such as the city design, which are difficult to assess. However, there are objects that are so popular that they can easily be critiqued by non-specialists, such as cars, for example, which are real objects of use.

Do you have any particular role models who inspired you in the past?

There is one in particular, Peter Behrens, especially for the eclectic and coordinated work he did for the AEG, for which he designed the brand, took care of all the graphic design and designed the architecture, harmonising all these areas like and orchestral conductor and giving form to what today we would call the company’s corporate identity.

What do you think of today’s architecture compared to when you started your career?

If architectural design, the discipline of architecture, is in crisis at the moment, then it is partly down to the clientele, by virtue of which it no longer participates in this will to improve people’s quality of life, but actually serves purposes that have more to do with finance and real estate investment.

All of the characteristic elements of architectural design such as the context, relationships between shapes, the body, et cetera, have fallen by the wayside and in doing so have placed the entire practice in crisis. Years ago, I edited, with others, an edition of ‘Rassegna’ called “Le Corbusier’s Clients”, and that was when I understood that the clients of major architectural projects have always been a very active participant – working with Mr Citrohan meant working with a man who had clear ideas.

All these elements that we are discussing, such as the purpose, the vision, the commitment… are also valid for industrial design. Industrial design has always been affected by these issues too, and so instead of responding to the attempts to improve quality of living and of life in general, it has become a system of production of objects designed by marketing.

If you had to give a young person who has just enrolled on architecture some advice, what would it be?

I was talking about the purpose of architectural design earlier, namely to “change the world”, which I have always believed in, ever since I was a student. To young architects, I would say keep trying to change the world, push yourself to do this.