The professor of the Politecnico di Milano was the protagonist of the restoration of the old hospital originally designed by il Filarete, now the headquarters of the Università degli Studi di Milano.

The Ca’ Granda in Via Festa del Perdono in Milan is one of the city’s symbolic buildings: today it houses the headquarters of the State University but also hosts important events, such as the Fuorisalone, during which its courtyards are filled with original design installations. Yet not everyone knows that the Ca’ Granda was an important part of the history of Milan because it housed the city’s first major hospital until the first half of the 20th century, when the bombs dropped during the Second World War hit it hard. Its rebirth is due to a great architect and professor of Politecnico di Milano: Liliana Grassi.

The great Milan hospital commissioned by Francesco Sforza

In 1451, Francesco Sforza promised the Milanese people that he would establish ‘a great and solemn hospital’, a promise fulfilled by the decree of 1 April 1456. A few days later, Duke Sforza and his wife Bianca Maria Visconti laid the foundation stone of the hospitale grando, combining sixteen Milanese hospitals with the aim of restoring Milan’s vocation as healthcare provider: hence the name “Ospedale Maggiore” (large hospital). The hospital was soon renamed “Ca’ Granda de’ Milanesi” (Grand House of the Milanese) precisely because it welcomed patients from all social backgrounds and areas (Italians from outside Milan and foreigners), and for its ability to attract donations from benefactors and many volunteers.

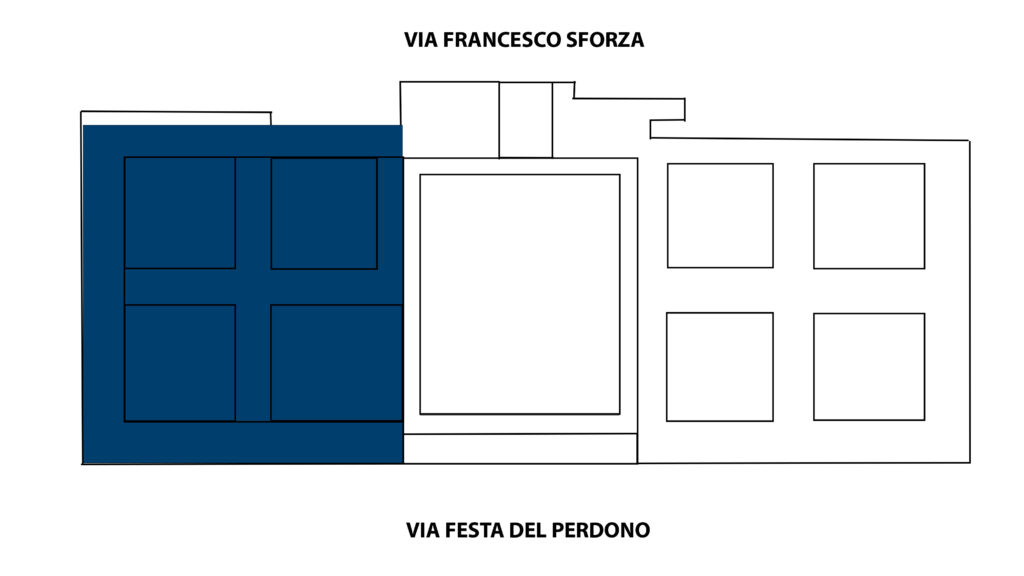

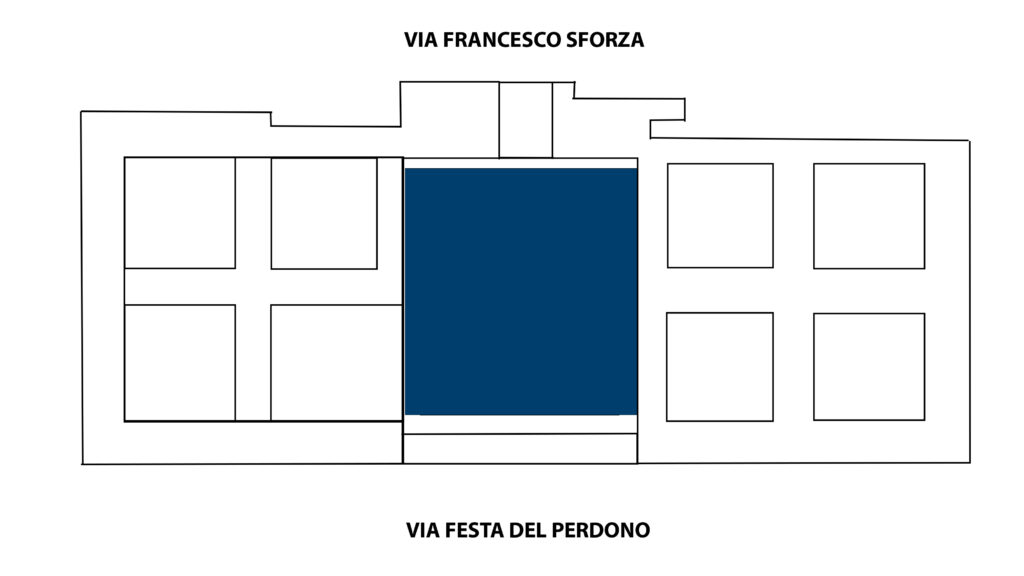

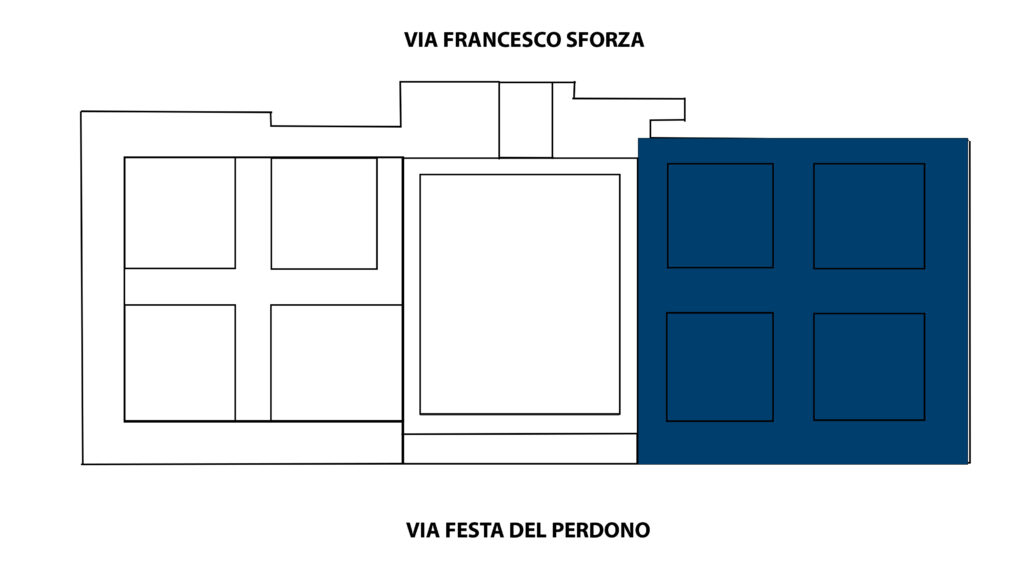

Antonio Averlino, known as il Filarete, was appointed to create the new design, which included two cross vaults (one for men and one for women), inscribed in a square, in turn delimiting four internal square courtyards: these two large sections were connected by a courtyard with a church in the centre. Although the layout of the courtyards remained faithful to the original, the works took many centuries to complete, often due to lack of funds, and the demands of the climate and logistics resulted in some changes being made during construction.

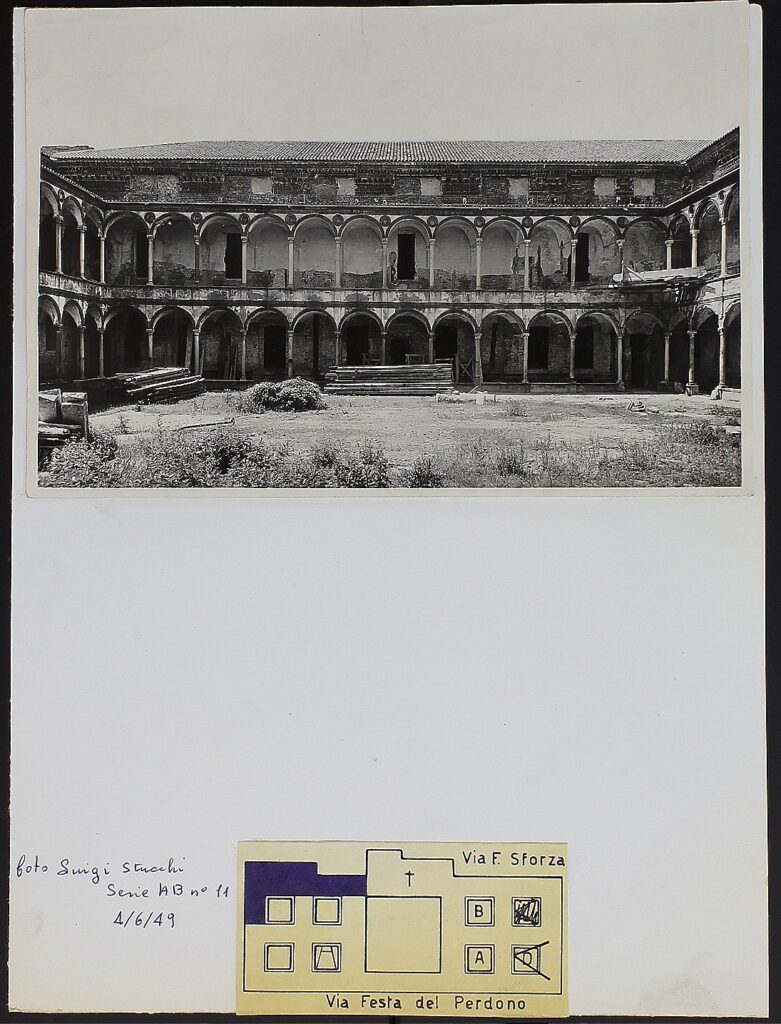

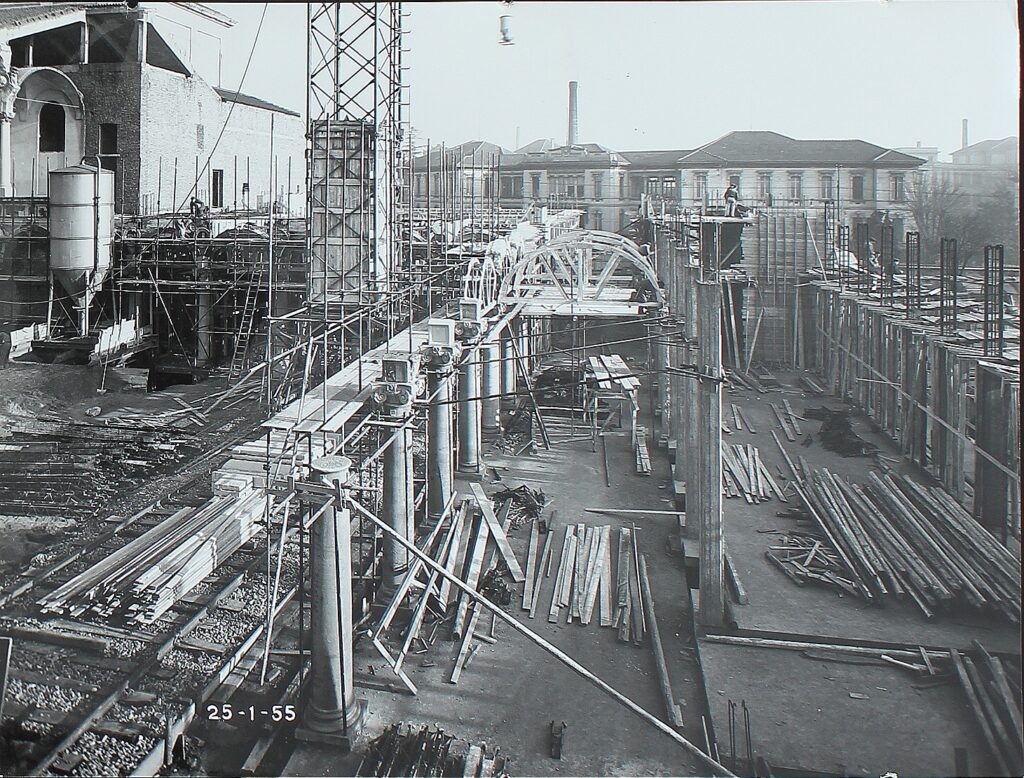

Between October 1942 and August 1943, Milan was bombed by Anglo-American forces: factories, railway stations, strategic military sites, but also religious and artistic buildings and schools were all targeted by the Allies. In particular, the bombs that fell between 13 and 16 August 1943 caused the partial collapse of the facade in Via Festa del Perdono, the destruction of the main courtyard and the porticoes, and serious damage to the cloisters.

Liliana Grassi

The protagonist of the restoration of the Ca’ Granda was Liliana Grassi (1923-1985), who graduated in architecture in 1947 and then became an ordinary assistant and freelance professor. Grassi was a professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Politecnico di Milano from 1960 to 1972 (Stylistic and constructive characteristics of monuments, Monument Restoration and Life Drawing 1), then at the Faculty of Engineering, where she taught Restoration Techniques until her death in the summer of 1985. She was also director of the Institute of General Drawing from 1972-82. She was responsible for the restoration of the Ca’ Granda in Milan (1948-1985), now the headquarters of Università degli Studi di Milano, at first working alongside Annoni and Portaluppi, then as the person in charge.

“The recovery of spatial and numerical values is not to be understood as a mechanical revival… but as a creative recovery of historical memory, achieved through an intangible relationship between the foundations that illuminate design research and the data of tradition”.

Liliana Grassi

The restoration of the Ca’ Granda

Grassi’s restoration work, which involved the addition of brand new parts, is based on scrupulous historical research, in which she painstakingly analysed documentary and iconographic sources to preserve Filarete’s work and style. This process was essentially concentrated in three phases.

Restoration of the 19th-century part

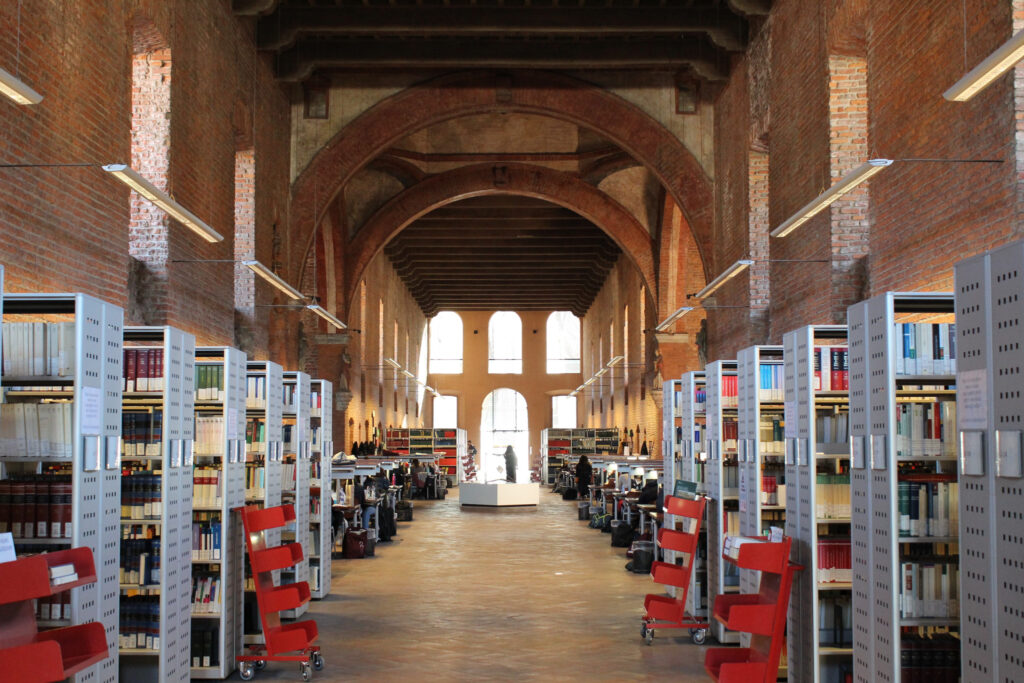

The first phase of the work involved the nineteenth-century wing and its arrangement for teaching purposes: here her intervention involved a great deal of creative manoeuvring, since the artistic value of this part was much lower than that of the rest of the building and because of the need to create suitable spaces for teaching (classrooms) for the State University.

In spite of this, Grassi decided to keep the cross plan, after an iconographic reflection:

“In his treatise, il Filarete never speaks of the semantic values of the architecture he designed and built, but only of its functionality”, – writes Liliana Grassi. – It is believed however that his choice was intentional. In fact, the attention he paid to buildings with a central plan, evident in his drawings and written observations, and his evident preference for this planimetric layout in his design choices, make it certain that, in conceiving his architecture, he was expressing, albeit at an unconscious level, his own culture and that of his time. In this context we can therefore find that ‘quid’, scientifically difficult to define, which directed the author’s choices.

… the profound destruction of the second cross vault, caused by the bombings, and the poor characterisation of three of its four courtyards called into question the need to follow the layout of il Filarete in the design of new parts, raising the problem of the possibility of solutions free from the pre-existing conformation (…) but a more mature and conscious reflection of the problem led to the decision to conserve it, in consideration both of the emblematic value of the cross vault layout (recurring in several buildings of various historical periods), and of the attitude that had characterised first F. M. Richini’s intervention, which had to maintain evident continuity with the part already built ‘according to the manner of the ancients’, and then also the 18th century completion, which had been adapted to the layout by il Filarete”.

Thus the new facilities for the Faculties of Arts, Philosophy and Law were built: the Aula Magna (created from one of the courtyards), the Rectorate, the graduation halls, the Seminaries, classrooms and toilets (along the arms of the cross vaults).

Restoration of the main courtyard

The second phase of the restoration was much more demanding: the restoration of the main courtyard. The restoration was carried out using the technique of anastylosis, i.e. the meticulous reconstruction of the artefact using the original pieces. A technique also promoted by the Athens Restoration Charter of 1931: “when conditions permit, it is good to restore the original elements found (anastylosis); and the new materials needed for this purpose must always be recognisable.”

This phase culminated in the 1958 inauguration of the new University building.

Restoration of the four cloisters

The third, final and most delicate phase was the restoration of the 15th-century wing, the four cloisters and the facade on Via Francesco Sforza.

For the facade, Liliana Grassi decided to preserve the original wall and build the rest of the facade without stylistic references: this ensured that it was not a simple juxtaposition of elements from different eras but a clearly visible story of the building’s history, complete with all its stratifications.

Numerous matches between philological and monumental data led Grassi to the discovery of the first mullioned window on the left and a series of terracotta cornices and foliage in the infill walls.

Denying the separation between the present and the past does not mean, of course, that the operative moment should be achieved by resorting to a romantic revival for which partial additions or total reconstructions in “style” are proposed under the guise of rigorous restoration. The solution to the problem depends on a global conception of the world in which it is fundamental to act in, or in the face, of time.

The destruction left by the bombing in Via Francesco Sforza also affected the Ghiacciaia courtyard. Here, too, the restoration proceeded by anastylosis, but only for the two sides because it was not possible to find the original pieces for the others, the bombs that had fallen there having pulverised everything.

Here too, as on the facade, the building was constructed by adding new parts: the perimeter of the old courtyard remains visible in the part that has not been recovered thanks to the bases and fragments of the columns. An operation which on the one hand evokes the structure but on the other makes us reflect on the destruction: in fact the author speaks of a “reinforcement somewhere between hope and memory”.

In the Cortili della Farmacia and the Cortili dei Bagni, Grassi’s work also aimed to highlight the traces that testify to the various phases of the building’s construction, without giving in to the temptation to turn the courtyard into a museum and thus crystallise it, but instead to perform an act of creative recovery, which is practically the idea behind her entire project:

“The recovery of spatial and numerical values – writes the architect- is not to be understood as a mechanical revival… but as a creative recovery of historical memory, achieved through an intangible relationship between the foundations that illuminate design research and the data of tradition”.

And thanks to its creative recovery, not only has the Ca’ Granda returned to its former glory, but with the establishment of the Università degli Studi di Milano it has once again become a place of growth for the Milanese community.

Images: Building site at the Ca’ Granda of Milan from Politecnico di Milano, University Historical Archive