We met Carlo Ratti on the occasion of his first lesson of his course as a visiting professor at the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering (ABC) of the Politecnico di Milano entitled: Strategic vision for the building Engineering for the future.

The Italian and foreign students, who welcomed him in a crowded and attentive classroom, knew they were faced with a guru of the cities of the future, with a fervent and curious mind.

Architect and engineer founded the CRA studio, in Turin and New York, and runs the Senseable City Lab at MIT in Boston, in this interview Ratti tells us, in an engaging and original way, his vision of the contemporary city, the hybridization between natural and artificial, the importance of Big data as a tool for interpreting the city and its needs.

What is your definition of architecture? City architecture?

In his “Kleine Schriften”, the German architect and critic Gottfried Semper said that architecture is “a complex with individual character, but at the same time in harmony with itself and its environment”. This harmony can be interpreted in many ways. Perhaps the most relevant is a new balance – or even a double convergence – between the two poles of the natural and the artificial. On the one hand, digital technology – with sensors, actuators and artificial intelligence – allows us to ‘animate the artificial’, for example by making buildings responsive and able to adapt to their surroundings in real time. On the other hand, there are an increasing number of projects that incorporate real pieces of nature: not only plant species, but also organic materials with which to create authentically circular projects. During the programme we will explore the main themes of the contemporary city, in particular how data technologies are shaping new ways of interpreting and designing the city. We will discuss this through the research we have conducted with the MIT Senseable City Lab. We will draw on computational science to understand how to adopt a data-driven approach to urban analysis. One interesting aspect is that the course will be held in English simultaneously in Milan and Boston, straddling the Politecnico di Milano and MIT.

In the light of the pandemic, a situation we are struggling to emerge from, how should we rethink our homes, our offices, urban mobility and universities?

I am confident that cities are already coming back to life, as has happened in recent centuries following pandemics even more devastating than Covid-19. However, I believe that the health crisis has had a major effect on our urban centres: innovation processes that would have taken years to implement have accelerated in a matter of months. Many cities have embarked on bold trials in sustainable mobility or public space management. Maintaining this momentum will be a goal for recovery in the coming months and years.

Your work has always been at the forefront in the field of Smart Cities. What changes should we expect in the coming years?

I don’t like the label ‘smart city’, which leaves the impression of technology as a mere technological accident. On the other hand, I like the idea of the ‘senseable city’, which seeks to combine digital sensors’ ability to ‘sense’ with a more human ‘sense’, understood as the ability to listen to and accommodate citizens’ needs in the city’s development.

What role does Big Data play in the design of urban spaces?

An important role. Digital technologies have radically transformed many aspects of our lives over the last two decades: from the way we work, to the way we communicate, move and meet each other. Similarly, today we are at the beginning of a new revolution: The Internet is entering physical space – the space of our cities, first and foremost – and turning into the so-called ‘Internet of Things’, bringing with it new ways of interpreting, designing and inhabiting the urban environment. An era in which technology is so ingrained in the space we inhabit that it can finally ‘recede into the background of our lives’, an omnipresent but discreet element. Hence the importance of data as a tool for interpreting the city and its needs. In one of our most recent projects developed with the MIT Senseable City Lab for the Porto Design Biennial in Portugal, we used geolocalised tweets and anonymised data from the mobile phones of tens of thousands of people to try to map new forms of social segregation: what the sociologist Richard Sennett and I have called ‘liminal ghettos’. These findings can help us identify where action should begin in order to make our cities more diverse and inclusive.

How can we rethink our cities and homes from the perspective of a circular economy?

As we said, we are currently witnessing increasing integration between natural and artificial. I believe that designers have a duty to accelerate this convergence, starting with architecture in which everything is recyclable or reusable (as occurs in nature). This is what we tried to do alongside Italo Rota, Matteo Gatto and FM Ingegneria at the Italian Pavilion at the Dubai Expo.

Will big cities like Milan still be attractive? Can you give us some good examples of cities in the world?

Cities today are outposts of innovation, each in a different guise. For example, Singapore has undertaken very exciting projects on future mobility, Copenhagen on sustainability, Boston on citizen participation, Milan on the integration of nature and architecture, and so on. As for attractiveness, I have no doubt that big cities, with their vitality and their offer of anonymity, will continue to attract people from all over the world. At the same time, small towns, as well as sparsely populated rural settlements, will continue to exist. Compared to the dystopian scenarios described by preachers, depending on the season, either the death of the metropolis and a return to villages, or the crisis of small towns swallowed up by large cities, the so-called ‘Zipf’s law’ provides a solid link to reality. George Zipf was a linguist who worked at Harvard in the first half of the 20th century. Applied to cities, his law states that the ratio between large and small cities will remain constant, and indeed that it follows a mathematical distribution. Of course, the big cities of the future might be bigger than the ones we live in now, but this does not mean that small cities will disappear or that the relationship between cities of different sizes will change.

Is the 15-minute city feasible?

After the crisis of post-war mono-functional modernism, urban planners and designers sought to inject diversity into neighbourhoods. That’s why I find the concept of the ’15-minute city’, conceived by my friend Carlos Moreno, promising. In every 15-minute neighbourhood, offices, parks, schools and shops could be accessible to everyone without needing to drive anywhere. There are of course critical aspects to be addressed, but in general, from a social point of view, these small sub-units are much more manageable and also foster community building. Projects embracing this approach are taking off all over the world. With our studio CRA, we have developed one such project in Milan: Parco Romana, the master plan we developed in conjunction with OUTCOMIST, DS+R, PLP Architecture and Arup to transform the area of the former Porta Romana depot into a residential neighbourhood and vast green area reconnecting the centre of Milan with the southern part of the city.

In designing the Italian pavilion for Expo 2020 Dubai with Italo Rota, your research was aimed at exploring the relationship between natural and artificial, within a dimension of hybridisation. How did you make it happen?

First of all, we asked ourselves how we could make this pavilion into a piece of reconfigurable, circular architecture that would not be dismantled at the end of Expo, as often happens after large temporary events. This led to the idea of a building with a multimedia façade made from two million recycled plastic bottles. It also makes use of innovative building materials – from seaweed to coffee grounds, orange peels to sand – and uses an advanced climate mitigation system as an alternative to air conditioning. Even the structure of the building itself explores the theme of reuse: the pavilion incorporates three life-size ship hulls in its roof, which could potentially sail after the event.

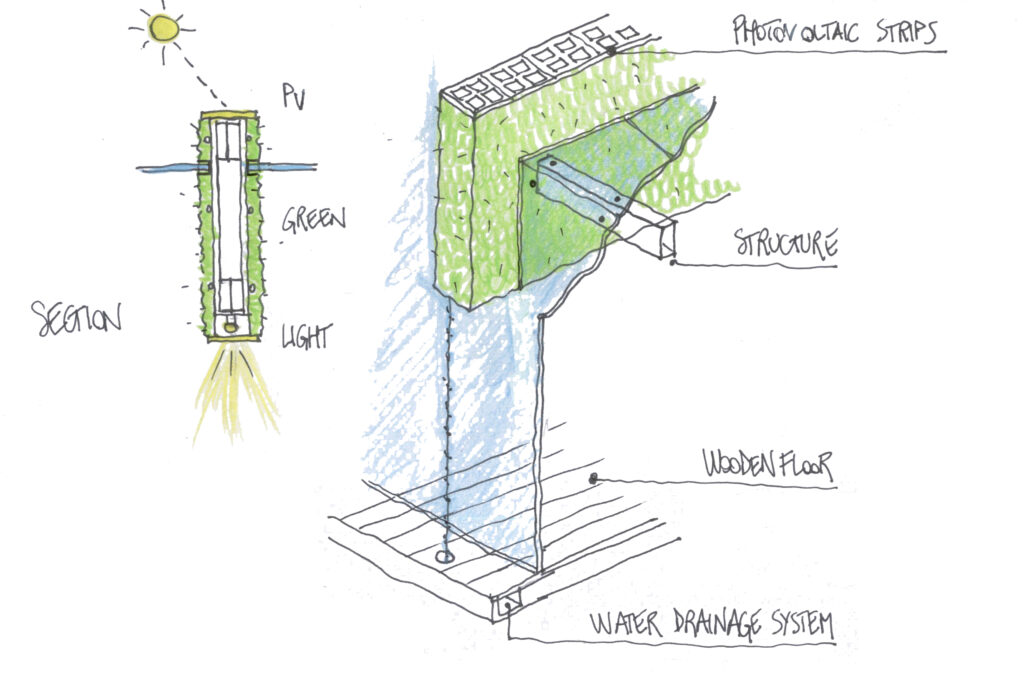

We are seeing more and more greenery being integrated into urban spaces, as you demonstrated with the Digital Water Pavilion designed for Expo 2008 in Zaragoza, which gave a fluid interpretation of architecture with its curtain of water welcoming visitors, or with the vertical green dome in Piazza della Scala in Milan for Maison Trussardi. How do you manage to find the right balance in your projects?

The intersection of the natural and artificial worlds is the field of research that inspires much of our work at CRA – Carlo Ratti Associati. A recent project is Francesco Mutti’s home in Montechiarugolo, near Parma, designed together with Italo Rota. The building winds around a ficus tree about ten metres tall, which is surrounded by all the domestic spaces on multiple levels. This is one of many examples of how we look for different ways to combine architecture, natural elements and technological solutions at CRA.

What results have your climate mitigation projects achieved and how could we reduce energy consumption in our buildings thanks to your studies?

There are many fields of research. One of the starting points was the fact that a lot of energy is wasted on heating and cooling large empty spaces – here the reference to one of our scientific articles from a few years ago. We tried to reduce this asymmetry by synchronising human presence with climate control. This resulted in two prototypes – Local Warming, presented at the last Venice Biennale, and CloudCast, installed for the first time in Dubai. These ideas were then fed into the project for Fondazione Agnelli, in Turin, a building equipped with a space control system. This research also continued with the CapitaSpring tower, which will be inaugurated in Singapore in a few months time. In the tower it will be possible to work in the midst of a tropical forest suspended in the middle of the skyscraper, thanks to very sophisticated climate mitigation systems. In short, thanks to Big Data and digital technology we can monitor energy consumption, modify it in real time according to user needs, and create new workspaces that bring us closer to nature.

Capita Spring Green Oasis (Photo: RENDY ARYANTO/VVS.sg)

As someone with such a multifaceted background, what advice would you give to a young architect?

There is a scene in Truffaut’s film ‘Jules et Jim’ that is significant to me. The bit where Jim recounts his dialogue with his professor Albert Sorel: “Mais alors, que dois-je devenir ?” — “Un Curieux.” — “Ce n’est pas un métier.” — “Ce n’est pas encore un métier. Voyagez, écrivez, traduisez…, apprenez à vivre partout. Commencez tout de suite. L’avenir est aux curieux de profession.” “Travel, write, translate, learn to live everywhere, begin at once. The future belongs to the curious“. That’s my advice.