Alessandra Mannocchi is 26 years old and comes from Cossignano, a small village of only 969 inhabitants lost in the Marche hills. She moved to Milan in 2015 to study at Politecnico Space Engineering and she also attended the Alta Scuola Politecnica. Since 2021 she has been working at the DART Lab where she started as a research fellow working on IMPRESA, a project born from the collaboration between the Politecnico di Milano and the Italian Navy. In November 2021 she instead started her path as a doctoral student, focusing on a topic closer to the master’s thesis, let’s find out which of her from her words.

Alessandra, how did your passion for research come about?

“At the end of my Baccalaureate oral exam in 2015, I told the Chair of the examining board that I was interested in becoming a researcher. At that time I had no idea what that really meant: I didn’t know what papers were, what a lab looked like, I only had a vague idea of conferences. And yet I aspired to it because I have always had a voracious curiosity for that which I didn’t know and to me to be at the frontier of knowledge seemed to be the only way to truly know why ‘the world works the way it does’ and at the same time give free rein to my creativity.

Now that I’m immersed in it, I can only partly agree with myself: research is independent, free, and therefore, suited to me, but the frontier of knowledge proves to be full of more questions than answers and this is often frustrating. I discovered, reluctantly, that one cannot aspire to definitive knowledge”.

Why Aerospace Engineering?

“I always had a penchant for scientific subjects: mathematics gives me a reassuring and familiar sense of order whilst I learned to love physics, which I initially hated because it was an approximation of reality which I could not understand, because it left me with a sense of disbelief every time it explained me the world in simple but precise rules, almost obvious once learnt. In addition to that, I have always had a vertical drive towards space, the stars, towards everything that is infinitely large and far away; not being able to understand it gives me a vertigo sensation which gives meaning to everything that I do, it puts me into perspective and gives me food for thought at the same time. Aerospace engineering, but even more space engineering, is, for me, a chance to reach that far-away space and the idea of being able to guide satellites through its immensity excites me”.

You are part of the DART Lab, what is it that you do?

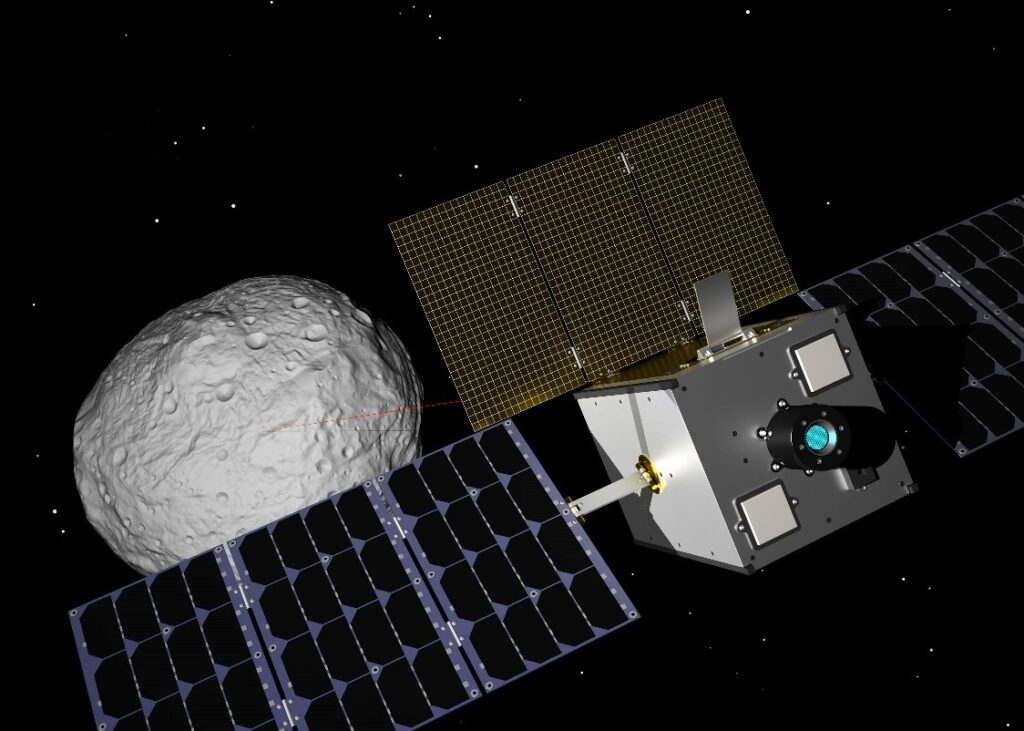

“We at DART Lab all work towards one goal: to bring complete autonomy to the navigation and control of interplanetary satellites. To date, we rely on input from Earth, but these inputs are a more than costly part of the total price of space missions. Our laboratory provides a more democratic and accessible vision of their future allowing us to lower the cost of entering space, thus making it accessible also to smaller research bodies and not only to large government agencies as it is today. Our laboratory hasn’t been around for long, but it is rapidly expanding and revolves around Prof. Topputo, who first told me of his vision. A vision which I made mine as soon as he spoke to me about it in his office almost three years ago, I fell in love with it: that is a myriad of miniature interplanetary satellites, CubeSats, which in the future will, fully autonomously, navigate and steer themselves through deep space, opening up scientific possibilities for our industry which can only be imagined today”.

What research are you working on at the moment?

“My research is focused on developing an algorithm which allows the satellites to calculate their own trajectories, relying only on their on-board computer and any pre-loaded data libraries. Currently the calculation and re-calculation of trajectories is done on the ground by dedicated personnel working at a fast pace with an inevitable delay in relation to the state of the satellite. The goal of my algorithm is to bypass this step. In particular, my PhD stems from a collaboration proposal, won in 2021, between the Politecnico di Milano and the European Space Agency (ESA), aimed at designing the first self-driving interplanetary space experiment. The idea is to bring the algorithm on board the M-ARGO, the first CubeSat designed by the ESA to travel autonomously between Earth and its target asteroid. My Master’s thesis dealt precisely with the calculation of this satellite’s particular trajectories, on which DART Lab has been working for some time”.

How much have your studies helped you to conduct research here?

“A lot. I moved to Milan in 2015 to study at the Politecnico, where I graduated with honours from both my Bachelor’s in Aerospace Engineering in 2018 and my Master’s in Space Engineering in 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, with a thesis titled ‘A Homotopic Direct Collocation Approach for Operational-Compliant Trajectories Design’. Throughout my Master’s I also took part in the Alta Scuola Politecnica project, which allowed me to get a second Master’s degree in Aerospace Engineering at the Politecnico di Torino. I would be lying if I said all of this was easy, that is simply not the truth. I took exams for which I spent sleepless nights studying and with names that would have seemed incomprehensible and pretentiously nerdy to me only seven years before. In my final year, I suffered unspeakably on exams such as Fundamentals of Structural Mechanics or Dynamics and Control of Space Structures. But, despite the overwhelming anxiety, I overcame all of those terrifying and endless moments of waiting between the end of classes and the beginning of the session, or between handing in an exam and receiving my grade. But thanks to exams I got to know what I love and now hope to continue doing in the coming years with my research: programming, developing driving algorithms. A big step up for someone who, seven years ago, did not even know what a code was or how a satellite worked”.

Any research projects for the future?

“In February 2023 I am going to the Netherlands to work at ESTEC, the ESA’s headquarters in Noordwijk. It still hasn’t fully sunk in that I will have the opportunity to access their labs with a card with my name on it. I’ve always admired the ESA from afar without believing I could actually access it. Now instead I will be able to work with people who have spent much more time in the industry than me and can bring my algorithm to life. I can’t wait”.

How do you balance your working life with your personal one?

“Generally I don’t feel as if I have to divide my life into two separate spheres, as I am the same person who lives them both, without contradiction or opposition. Research is a beautiful field because of the freedom it grants, but this very aspect can be dangerous, as there is the potential to never switch off. In contrast to those who work fixed hours, no one can stop me from thinking about my project in the evening or on weekends out of pure self-interest. Nevertheless, I feel that it is important for my mental well-being to establish boundaries within which I can give space and proper dimension to the obstacles that I might encounter throughout the course of my research. In my opinion that is the right philosophy for every aspect of life, so that it cannot become all-encompassing. That is, it cannot become a focus from which it is impossible to distance oneself, which overpowers the rest and limits our creativity and ability to change. So I have learnt over the years to cultivate other interests: I avidly go to the gym, almost every day my alarm is set for 6/6.30 to be able to go and lift weights at dawn. I also really like to walk, be it in the city, almost every evening I lose myself in the streets of Milan with a podcast in my ears, or in the mountains, where I challenge my endurance more and more each time, trying to reach a higher point, to walk up a steeper hill. I travel a lot, I do yoga and meditate recreationally. My biggest passions, however, are reading and writing. My house is overrun with books, everywhere I go I have at least one with me, and I have a blog where I share my poetry. I would love to publish them one day, but until then they will remain secret from prying eyes”.

Do you think research is harder for a woman?

“Especially in the field of aerospace engineering, to which I can personally attest, there is the perception that it is still male-dominated. If I think about my university courses, women have always been in the clear minority, even though things are slowly changing. Personally I grew up with a complete absence of prejudice and with my family’s total support in my choices, and so I never perceived my propensity towards the scientific world as a difference or an anomaly, however I am aware that it was my particular situation that brought me to where I am today, a place understood above all on a mental level. Still today the stigma of engineering work as being purely male is strongly ingrained: I sense it by the amazement invoked every time I reveal my job to someone I don’t know. This same stigma not only annoys me, but also distances women from the field, in a thus far vicious circle: believing it to be only a man’s world, girls are not initiated into it and thus the idea to enter it doesn’t arise in them naturally; by not entering into it, female representation remains low, making examples scarce.

Therefore, in general, no, research is not harder for a woman in my field as such, instead it’s harder to imagine a woman researching in my field. I notice that initiatives aimed at having greater female representation have grown exponentially in recent years. I believe they are necessary and yet unfair: I cannot wait to live in times, towards which we seem to be moving, in which these initiatives will no longer be necessary as research and work in general will be considered on a purely professional level. I cannot wait to be simply a person who works and that my being a woman, man or whatever, will no longer be sensational because it is no longer relevant”.

What is your greatest ambition?

“I don’t have specific ambitions at the moment, I’m happy with what I have. I hope to continue to be able to grow as a person, to learn, to gain as much experience as possible, for example by living abroad for a while, but I don’t have specific goals: I know that, given the amount of information I’m receiving about this field, it could change within a year. My greatest ambitions would concern my personal development, and that would be to become more mature, find my own balance and simply live peacefully”.