The mimosa pudica’s journey is a long one. This evergreen plant, native to Central America, landed in the DABC MaBa.SAPERLab – Department of Architecture, Built Environment, and Construction Engineering – where Fabio Bazzucchi, first as a visiting researcher from MIT in Boston (where he was as a Postdoctoral Fellow Marie Skłodowska-Curie at the Senseable City Lab) and now as a researcher at the university, under the guidance of the department’s scientific coordinator, Ingrid Paoletti, is studying the properties of this unique plant for the design of dynamic and responsive architectural elements.

Mimosa pudica (aka sensitive plant) is truly unique and has fascinated researchers and scholars in every field for centuries: from Charles Darwin to Robert Hooke, father of Hooke’s law of elasticity. The reason for this interest can be found in the plant’s name: indeed, it is called ’sensitive’ because it folds back its leaves if a foreign body comes close to it and, if touched, it closes them following a precise pattern, in pairs – and even, in extremis, instantaneously fully closes them if, for example, it is dropped. These reactions are unexpected in a plant organism and many different interpretations have been suggested, all valid but so far none conclusive: the first that comes to mind, of course, is that it is a self-defence mechanism, of which, moreover, the plant appears to retain a memory.

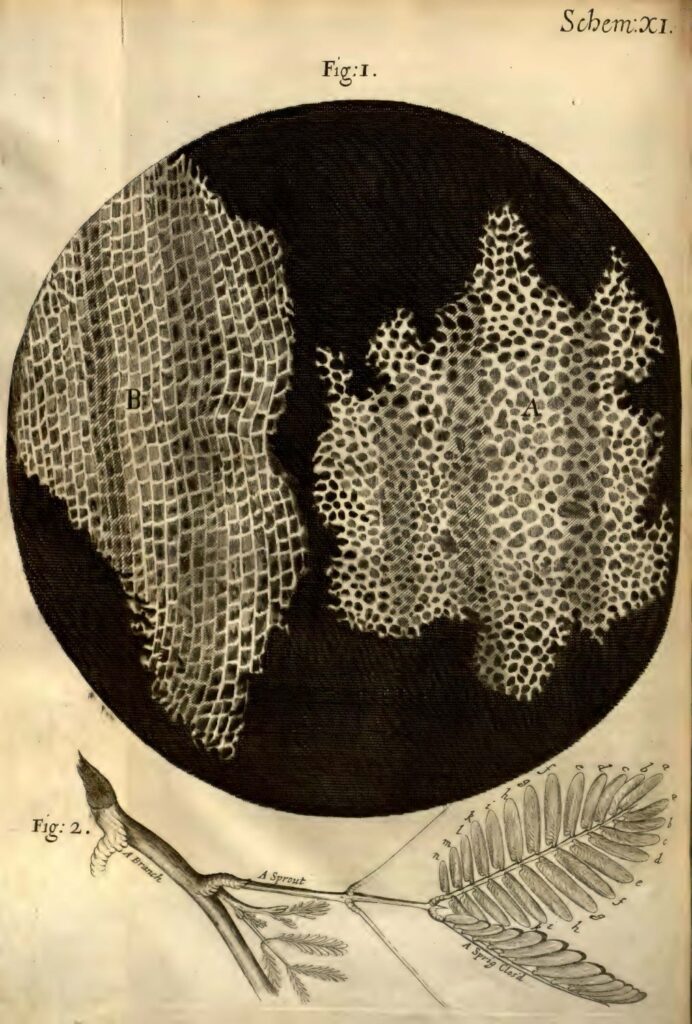

Front cover and a drawing of the mimosa pudica from “Micrographia”, a book by Robert Hooke, Biodiversity Heritage Library (CC BY 4.0 License)

The secret? The “snap” in its stem

In practice, the secret of its responsiveness lies in the pulvini, those joint-like organs that connect the stalk to the leaves, following hierarchical orders down to the petioles. The assumption is that a “snap” occurs that makes them close: «Elasticity is concentrated in a single point where the movement takes place, the pulvini – says Bazzucchi explains – The pulvino of mimosa pudica is unique in that it is convex but can become concave following the movement. On its own, the change in the turgor pressure in the tissues, caused by osmotic regulation, cannot explain the speed and effectiveness of this movement. Instead, a snap can be used to describe a rapid change in shape, through accurate calibration of the forces acting on it. In short, it’s as though the geometry of the pulvini contains perfect properties both to feel and respond to external stimuli».

These observations, before this research got underway, were the premises of the co-authored article published in 2023 by Bazzucchi and Ingrid Paoletti, who had previously discussed their respective studies and mutual interest in mimosa pudica. «The current state of the art of this plant’s description does not take into account the snap hypothesis. Instead, Professor Paoletti and I began to study whether, at the macro level, the movement could be considered a snap, that is, a loss of stability – a transition between two states of equilibrium. In our article, we discussed whether this could be taken as an interpretative model of its movements. I am a civil engineer, my doctoral thesis dealt with issues linked to very slender structures, close to the mechanics of materials, and Professor Paoletti was keen to understand if these systems could have practical implications for architecture. So, during our research, we focused on the mechanics of the plant itself. We began with a mathematical study that we used in the following phase of the study: we devised a model in which we imagined that the plant’s “intelligence” resides in its material organisation, in how it grew and developed, and above all, adapted. Its tissues are arranged in such a way that it can be intelligent in its environment. And since the MaBa.SAPERLab laboratory studies materials in their broadest sense, we are attempting to explore how materiality and intelligence can somehow merge. Because our brain also has a shape, folds, that are functional to its purpose, so the key to interpreting the capabilities and intelligence of the plant, whose tissues we are now studying, lies in the arrangement of the material. The idea is to create architectural elements that are responsive or sensitive to the environment, so-called smart materials that respond, like mimosa pudica, to stimuli such as light, heat, shock, touch».

The goal: new materials for “changing” surfaces

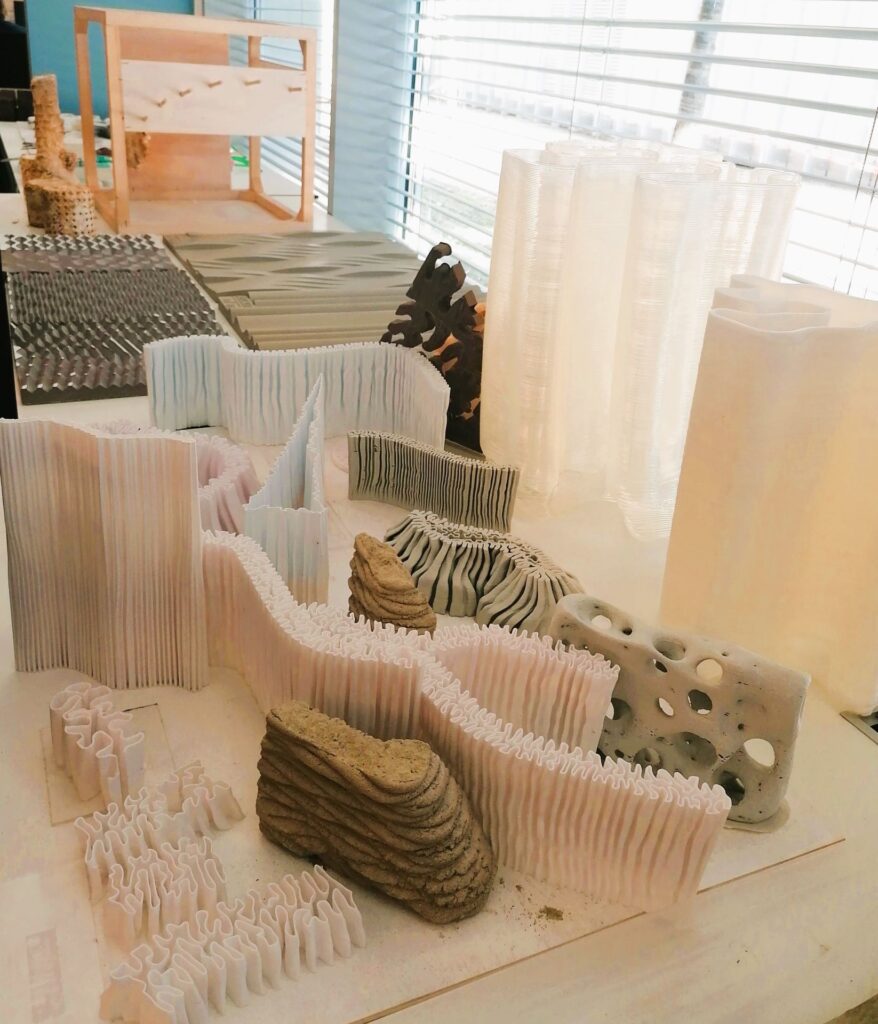

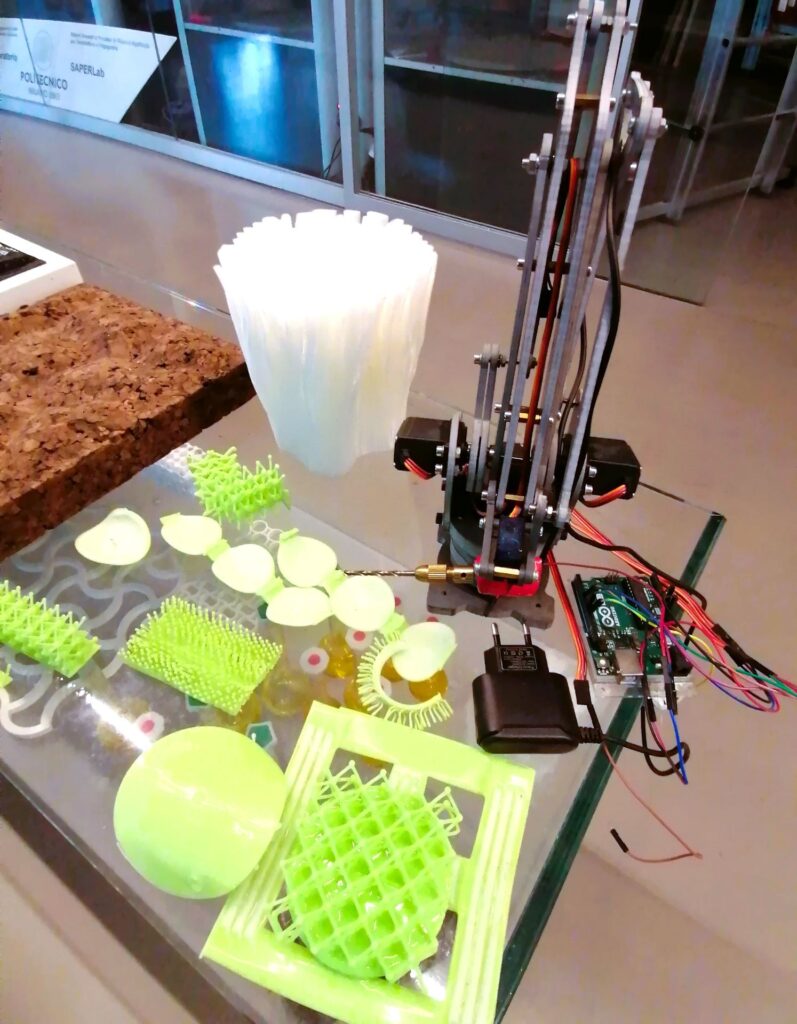

So how could the materials obtained in this way be used? «We imagined surfaces that change shape rapidly, panels whose surface or texture can rapidly change their configuration. This could be useful for tactile experiences, but also to create acoustic, visual or perceptual comfort in general. Because static shapes and geometries are very stressful for the human brain, like being in an environment where nothing ever changes, which is anything but natural. At the start we devised a sound-absorbing, responsive panel, because snap systems are often used for shock-absorbers, i.e. systems that absorb a shock through successive snaps. But the possibilities are endless».

The next step is the 3D printing of a module prototype: «The mathematical studies were carried out with a view to understanding if an interpretative model involving a snap could be used to understand and reproduce it – continues Bazzucchi – A snap is a tuned mechanism, it is a system that passes from one configuration to another, while a gradual movement is as if it were stable at every point. Using this mechanism, the surfaces we are attempting to develop can undergo a sudden, immediate change; the next goal is not to achieve a simple on-off position like that of the plant, but to create surfaces that could perhaps have even up to 10 configurations, and we are working on patents in this regard».

Back to… nature

Compared to the numerous studies on snap systems – which Bazzucchi himself analysed in depth during his studies – the difference here is that the starting point is a natural system, in line with a new engineering trend: «After the grand positivist engineering of the industrial revolution with megastructures, bridges and steel at its heart, we now understand that this emancipation from the natural world has somehow distanced us from it, with all the ensuing damage. Studying natural systems shows us that it is there that the real complexity lies. Nature, through evolution and adaptation, has developed extremely complex solutions. The mimosa pudica, which is about 12 centimetres tall, is a very simple, slender plant comprising just a handful (so to speak) of cells but it is much more complicated than anything we engineers could mastermind if we tried to reproduce it – concludes Bazzucchi – And you can’t say that it is not intelligent».

And as Bazzucchi points out, not surprisingly, the title of the Biennale Architettura 2025 is “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.”: a focus on multiple and diffused intelligences: human, natural and artificial. A newfound deference to nature that is then taken as inspiration, and almost emulated in this research project, as the Scientific Coordinator Ingrid Paoletti explains: «Studying the movement of the mimosa pudica can allow us to study technologies and materials in such a way that they can respond to stimuli by adapting to conditions in a variable, original and innovative way, making the surrounding environment “reverberate”».