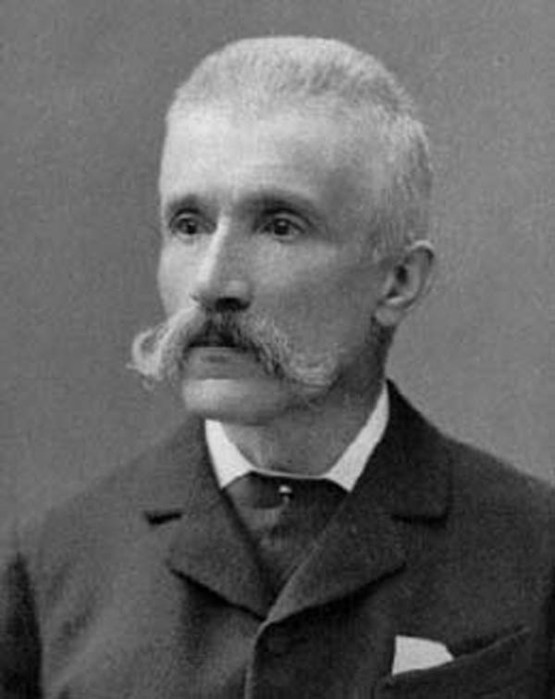

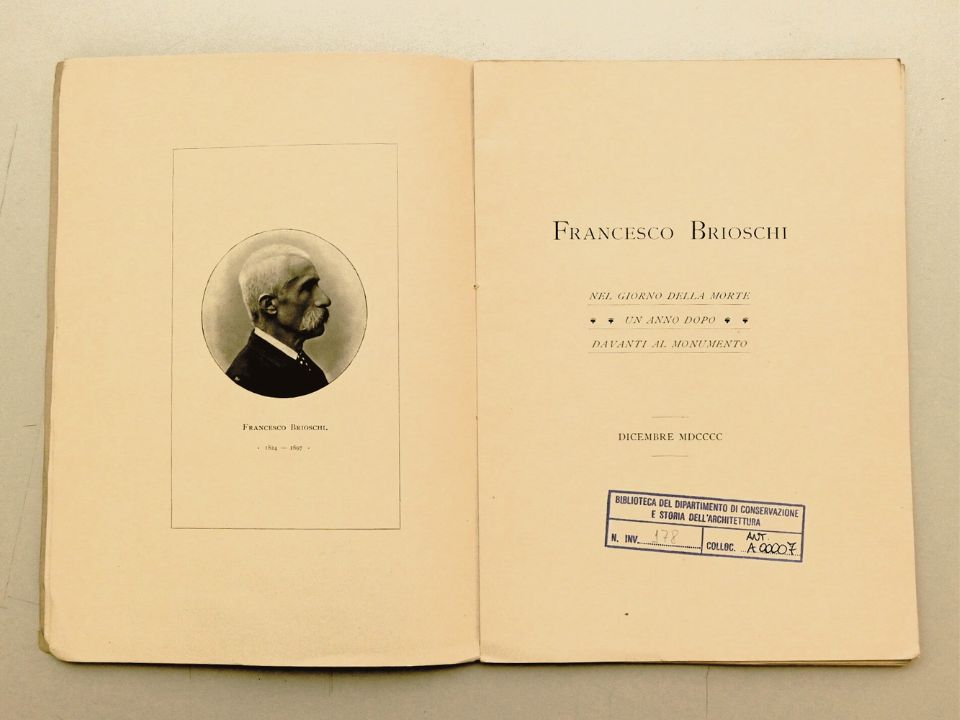

On 22 December 2024, we celebrated the bicentenary of Politecnico di Milano’s first Rector Francesco Brioschi’s birth. To honour his legacy, we revive our founder’s spirit through this “impossible interview.”

Mathematician and politician Francesco Brioschi pioneered original scientific research and played a key role in the political landscape of his time. As the founder and director of the Istituto Tecnico Superiore in Milan, which later became Politecnico di Milano, Brioschi was a leading figure in the Italian mathematical community. An intellectual with remarkable vision, he successfully combined scientific exploration with a deep commitment to the country’s civic and cultural.

To mark his 200th birthday, Frontiere “interviewed” him in his Palazzo della Canonica study.

Professor Brioschi, thank you for agreeing to this interview. It is an honour to interview the founder of Politecnico di Milano. Could you tell us a little about your background?

I was born in Milan in 1824 and was fortunate to grow up in an environment that valued knowledge. I studied mathematics at the University of Pavia, where I graduated at 21.

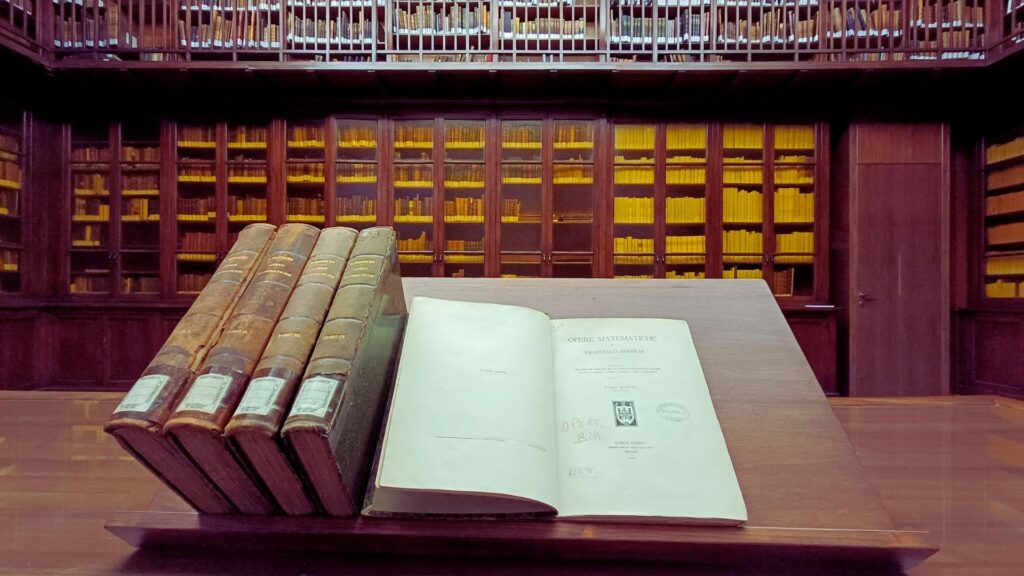

I quickly realised that mathematics was my true calling, thanks to the encouragement of Dr Piola, who had great faith in my abilities. Much of my academic work was dedicated to mathematics— publisher Hoepli compiled my 279 published articles into five volumes. I understand that a complete set of my works is housed in the Historical Library of Politecnico di Milano, thanks to a generous donation from the Department of Mathematics.

My interests have always been wide-ranging. I pursued applied research in physics, mechanics, and hydraulics during my career.

At Frontiere, we enjoy discovering the individuals behind the researchers. What about your political commitment? How did you experience the turbulent years of a nation yet to be born—Italy?

I have always believed that political involvement is essential to engage with one’s historical period. In our generation, this awareness was instilled in us from a young age. There was a nation to liberate and a new state to build.

That’s why I became actively involved in the patriotic movement in Lombardy. At first, I was drawn to Mazzini’s ideas. Like many of my contemporaries, I took part in the Five Days of Milan, but on the very first day of the uprising, the Austrians captured and imprisoned me in the Castello Sforzesco. Fortunately, the insurgents freed me shortly after.

After the Austrian restoration, I remained committed to the resistance, working within the Milanese central committee. However, by 1850, I shifted towards more moderate views, aligning myself with the independents gathered around Carlo Tenca.

That was the year you embarked on your academic career, wasn’t it?

That’s right. It was an incredibly intense decade for my research and teaching. In 1850, I was invited to the University of Pavia as a substitute lecturer in hydraulic architecture and applied mathematics. By 1853, I had secured a full professorship in the latter. from 1859, I was a full professor of higher analysis.

On the publishing side, my treatise “La teoria dei determinanti e le sue principali applicazioni” (The Theory of Determinants and Its Main Applications), published in 1854, was recognised as one of the subject’s most authoritative works.

I was fortunate to have brilliant students, including Eugenio Beltrami, Felice Casorati, and Luigi Cremona, who later made significant contributions to the field of mathematics.

Many consider you one of the key figures in the revival of mathematics in Italy.

I had strong connections with foreign universities and some of the greatest scientific minds. These relationships gave me access to the latest research methods and broadened my perspective.

Together with Cremona, I co-edited the “Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata” (Annals of Pure and Applied Mathematics). I launched this publishing venture in 1858 alongside Barnaba Tortolini, Enrico Betti, and Angelo Genocchi, driven to create an international mathematical journal. The goal was to establish a journal that would swiftly disseminate the findings of Italian research and attract the international scholarly interest.

You have been deeply involved in organising scientific studies, haven’t you?

Indeed, I have been engaged in national and local institutional life since the age of 35. I briefly served as the rector of the University of Pavia and, between 1861 and 1862, held the position of Secretary General at the Ministry of Education.

In 1859, I contributed to drafting the Casati Law, which reformed the education system and made the first two years of primary education compulsory for the first time. This was a significant step forward for the progress of our country.

In 1862, I was elected as a Member of Parliament, and in 1865, I was appointed a Senator of the Kingdom

Over the years, I have been honoured with various recognitions for my contributions to science and education, for which I am truly grateful. Among the titles I cherish most are my membership and vice-presidency of the Lombard Institute of Science and Letters, and my role as a member and later president of the Accademia dei Lincei.

During your time on the Higher Council of Public Education, you made Euclid’s Elements the foundation of the mathematics syllabus in secondary schools. Do you still stand by this decision?

Of course. I have always viewed mathematics as a means of intellectual development, a form of mental training that sharpens reasoning and helps distinguish truth from illusion. Euclid’s Elements remains the finest example of geometric rigour. There is nothing quite like the purity of geometry to instil the habit of precision and logical reasoning in young minds.

In 1868 I edited a new edition of the Elements with Betti. Despite the controversy surrounding its introduction, I firmly believe it was a vital reform—replacing commercial textbooks of dubious quality with a rigorous, scientific approach.

You are widely regarded as the Politecnico di Milano’s founder. How did this idea originate?

In 1858, along with Betti and Casorati, I embarked on a study tour of Europe’s leading scientific centres— Göttingen, Berlin, and Paris. This journey marked Italy’s emergence on the European mathematical stage.

It was an opportunity for me to study first-hand the most advanced institutions of higher education, such as the École Polytechnique, École Normale in Paris, and the German technical institutes. This experience proved invaluable in shaping the vision for what would later become the Istituto Tecnico Superiore—a higher education institute dedicated to training engineers.

In your view, what role should scientific and technical knowledge play in a newly unified Italy?

I have always believed that scientific and technical education was fundamental to social and economic progress. For Italy to modernise and compete with longer-established European powers, it was essential to invest in these fields.

Educational institutions cannot fulfil their high purpose unless their structure evolves to meet the demands of contemporary science and society. At the time, Italy desperately needed engineers and technicians to face industrial and infrastructural development challenges.

The Casati Law played a crucial role in this transformation. It established two new higher education institutions in Milan—a city without a university at the time. These were the Accademia Scientifico-Letteraria, which later became the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy at the University of Milan, and the Istituto Tecnico Superiore, which would evolve into the Politecnico di Milano. I was entrusted with the leadership of both.

What was the objective of the Istituto Tecnico Superiore?

Its purpose was to train civil and mechanical engineers, teachers for technical secondary schools, and serve as a free academic centre for scientific and technical advancement.

In 1863, the Istituto Tecnico Superiore di Milano was founded. It was a model of elite higher education that balanced pure scientific research with practical applications.

Here, I taught river hydraulics and mathematical analysis, serving proudly as its president and director for the remainder of my life.

You must be aware of the nickname some students jokingly gave the school due to its strict academic standards. Did you take it in good humour?

Ah, you mean “Brioschi’s Kindergarten”, don’t you? I must admit, I was particularly strict about attendance, punctuality, and the seriousness with which students approached their studies at the institute. Yes, we required classes from Monday to Saturday, but in return, we provided our students with workshops, hands-on training, educational visits to industries, exhibitions, and cities of artistic and architectural importance—places where the future of engineering and design was being shaped.

I was confident that the discipline we instilled in our students would ultimately benefit them, making their expertise highly valued and sought after.

The institute you led was later renamed Politecnico But a Politecnico had already played a role in your life before that?

That’s true. In 1866, I took over as editor of “Il Politecnico”, the magazine founded by Carlo Cattaneo, who, sadly, was still in exile in Lugano. The publication had ceased in 1845, and when it was revived, I was entrusted with its direction.

Although Carlo and I had some political differences, but there was continuity between our intentions. Like the original series, the aim was to provide readers with original research and in-depth reviews across a wide range of subjects—from the exact sciences to literary criticism—to promote technical-scientific and civic progress.

However, as the arts advanced, I decided to divide the journal into two sections: one focused on literature and the other on technical studies. The latter documented the country’s industrial and scientific progress. After three years, we discontinued the literary section and focused solely on the technical aspect, which later became known as the “Giornale dell’ingegnere.”

Among your many scientific contributions, you made significant advances in mathematics.

Yes, I worked extensively on the theory and application of determinants in matrices, publishing my findings in “Teoria dei determinanti” and “La teoria dei covarianti e degli invarianti delle forme binarie, e le sue principali applicazioni” (Theory of Determinants” and “The Theory of Covariants and Invariants of Binary Forms, and Its Main Applications).

Can you explain your work on elliptic and abelian functions?

Ah, elliptic functions! A potent tool for solving complex problems, which has opened new perspectives in mathematics. My research focused on these functions in relation to algebraic equation theory, particularly the general solution of fifth-degree equations.

As part of the theory of abelian functions, which extend elliptic functions, my research has focused on hyperelliptic functions. I worked on the algebraic resolution of high-degree equations, the invariants of hyperelliptic curves, and the connection between algebraic transformations and the properties of hyperelliptic functions.

Later, I succeeded in solving the general sixth-degree equation using hyperelliptic functions.

Have you also worked in the field of hydraulics?

Yes, I dedicated considerable time to water-related issues, in hydraulic construction and water resources planning and management. I contributed to projects involving Lombardy’s canal network, vital to the region’s economy, and plans for regulating the Po and Tiber rivers.

How would you describe yourself as a scholar?

I used to joke that I was just a calculator! [laughs] While I wouldn’t claim to have laid the foundations for new branches of mathematics, I would say that I had an eye for recognising the value of new ideas and envisioning how they could be applied to drive scientific progress.

And I always insisted on being called an engineer. Serving as president of the Collegio di Milano was one of the greatest honours of my life.

What do you see as your legacy?

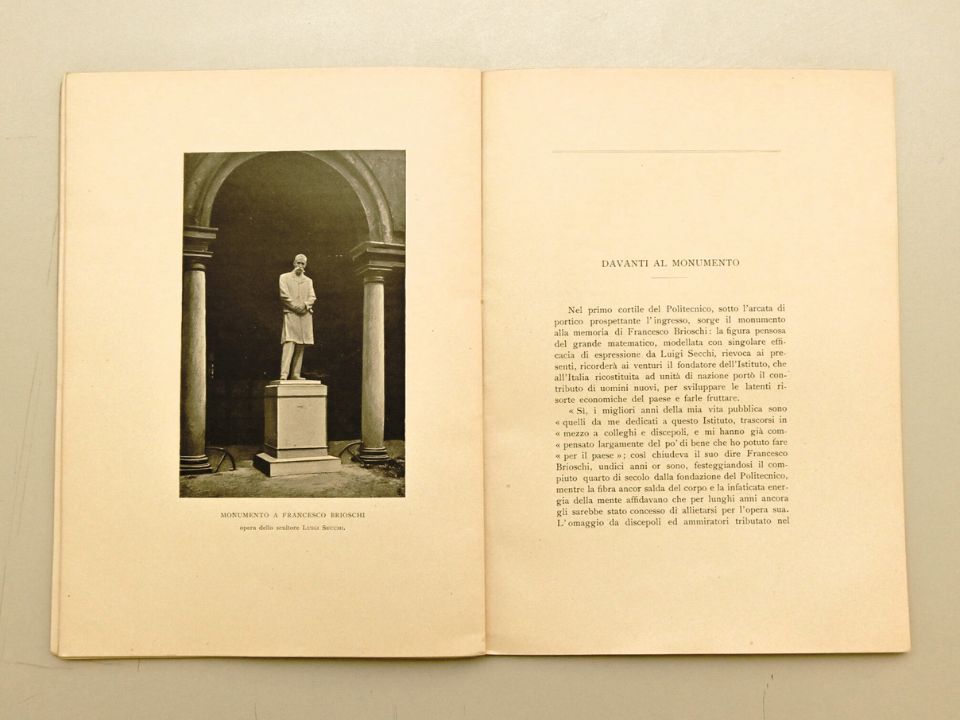

I hope my work demonstrated that science, education, and technological advancement are deeply interconnected. Politecnico di Milano is my most tangible legacy, and above all, I hope that my approach to mathematics—and life—has inspired those who came after me.

Thank you very much for your time, Professor Brioschi. It was an honour speaking with you.

Thank you. I am glad to see that my work continues to live on through Politecnico di Milano and is still remembered today.