One of the purposes of scientific research is to produce results that benefit society. Research results are the intellectual property of our University and can be protected by patents. The patent is the right to produce, use and exclusively market an invention – a new idea that has an industrial application – for a maximum of 20 years.

Every year, at Politecnico di Milano there are about 200 technological inventions that aspire to become patents. About half of them cross the finish line. Technological research is the purview of the Technology Transfer Office (TTO), whose mission is to support researchers, students, and teaching staff transfer scientific knowledge from the laboratory to the market.

At Frontiere, we have thought of a monthly column to understand how, each year, the best ideas envisioned on Politecnico University’s desks and laboratories are brought to fruition. And how they might affect our future.

The column’s first guest is Hybris, a patent filed in 2016, and brainstormed during a course delivered at the Politecnico di Milano. Students and their ideas are the focus. And we are speaking of ideas that could potentially have an important impact on our lives. The patent aims at the air transport industry, which, according to pre-Covid estimates accounts for two per cent of total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions worldwide. For this reason, there has been more talk of electric planes as a natural evolution of cars, mopeds and electric scooters that already abound in our cities. Airplanes have an underlying challenge, which the technology behind Hybris proposes to solve.

HOW THE HYBRIS PATENT WAS BORN

Let’s start from the origins, and the context within which this idea was born. We are in the last semester of the last year of the Laurea Magistrale (equivalent to Master of Science) programme in Aeronautical Engineering. One of the courses taught was “Aircraft Project”, delivered by Professor Lorenzo Trainelli. The name says it all: during the course, students were expected to design a complete aircraft. An ambitious goal which offered fertile ground for innovative and disruptive ideas, such as a special hybrid electric aircraft equipped with a two-component propulsion system. The idea was to design a real plane starting from scratch. In the Hybris case, it eventually led to filing of an international patent.

THE BATTERIES ARE “DIFFUSED”

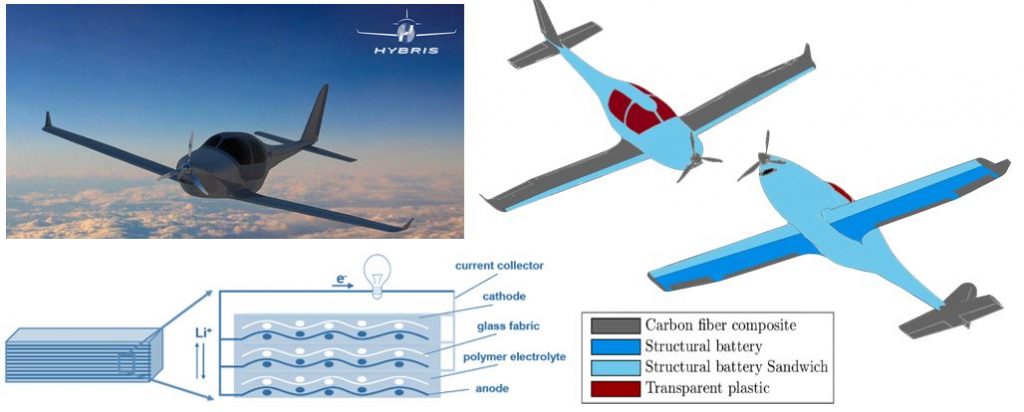

Hybris is a light hybrid electric aircraft, and its uniqueness lies in the fact that it has been designed to use structural batteries. Structural batteries have a two-fold nature. They are batteries which can store and make electricity available. But these batteries can support loads and become an element of the aircraft structure. We call them “diffused batteries” and they solve one of the fundamental obstacles to the transition to eco-sustainable aviation. Which obstacle are we talking about? As professor Lorenzo Trainelli, one of the inventors of the Hybris patent, explains: “Electric batteries are too heavy. Their weight dramatically impairs the aircraft’s performance making battery-based applications in the air transport sector difficult.”

For this reason, the decision was made to use structural batteries, whose technology is not yet at a high TRL (Technology Readiness Level), or not yet completely mature. Nevertheless, the technology has reached an advanced testing state. In the case of Hybris, the structural batteries make up almost all of the fuselage and the outer portion of the wings. They are an essential part of the aircraft structure, and avoid an extensive use of electric batteries, which, once spent, would only be “dead weight” for the aircraft.

BENEFITS

In addition to containing the weight of the aircraft, and achieving a promising performance, Hybris can cut operating costs by about 20 per cent. There is the significant reduction of CO2 emissions, which was our story’s starting point. The patent is friendly to both the environment and people. The use of a hybrid electric engine would reduce noise pollution, especially during take-off and landing. Which are the two most bothersome moments for the population on the ground.

POSSIBLE APPLICATIONS: THE REGIONAL AVIATION MARKET

How could Hybris practically be used? Professor Trainelli said that the regional aviation market is the ideal target of this patent. “To date in Europe regional aviation is weak, limited and unable to offer a valid alternative to driving. Few airlines offer a regional service and, when they do, it is mainly for feeding reasons (taking passengers to large airport hubs from which they then board another flight). Regional aviation is significantly different from the way the European Union understands it, i.e. a service to promote and increase the mobility of citizens”.

Flightpath 2050, a document drawn up by the European Commission, tries to envision the long-term future of aviation and includes among the objectives the goal of ensuring that, in about 30 years, 90 per cent of citizens will complete a trip within Europe within four hours at most. Imagine a trip from Lecce to Reggio Calabria. By plane, it is an absolute hassle (at least a stopover in Milan or Rome is needed), and far from efficient when it comes to the environment. By car it takes more than five hours, by train almost twice as long. Both cities have an airport and, an electric aircraft using Hybris technology would drastically cut the travel time.

Professor of Fundamentals of Mechanics of Atmospheric Flight and co-author of the patent Carlo Riboldi said: “Regional aviation based on electric aircraft would have a huge impact on the mobility of citizens.” There are tremendous opportunities. Throughout Europe, there are about 3000 small airports that sit idle or that only serve flight schools. Instead, these small airports could be used to support regional aviation based on electric aircraft. In addition to offering a convenient service to citizens (without environmental and noise pollution), electric aircraft could contribute to reducing traffic on roads and motorways also when it comes to the transport of goods, perhaps reducing the number of trucks traveling from one part of the continent to another.” Trainelli and Riboldi have been involved for several years in the electric aviation sector, by participating in a variety of projects funded by the European Commission (MAHEPA, UNIFIER19, SIENA).

THE INVENTORS

There are eight people on the Hybris invention team. In addition to the two professors, Lorenzo Trainelli and Carlo Riboldi, a researcher, Federico Gualdoni, and five students (who, by now, have moved on to their careers), attended that year’s “Aircraft Project” course. Among them there was an Erasmus Programme female student from Spain. With their work, they won a competition held by the world’s most prestigious aeronautical institution, the Royal Aeronautical Society, in 2016. The decision to call the project Hybris is related to this competition and was inspired by the Greek word connoting those who nurture excessively high ambitions. Team leader Alberto Favier told us: “We chose it precisely because we felt like we were being too conceited in our desire to participate in the competition to showcase the application of such innovative technology.” If you want to learn more about the team and its story, we chronicled it here.