The 2008 financial crisis had global repercussions, causing negative effects even on economies that were not directly impacted. One of the channels of this spreading effect were international production chains. A recent study “Financial Crises and the Global Supply Network: Evidence from Multinational Enterprises”, published in the Journal of International Economics, examines the effects of the crisis on multinational firms and how they reorganised in response to the financial shock.

To learn more about the implications of this study, we spoke with one of the study’s authors: Giulia Felice, Professor of Economics at the Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering of the Politecnico di Milano.

Could you tell us about your educational and research background?

I graduated in Economics at Bocconi University and subsequently completed a PhD in Economics at the University of Pavia. My doctoral research focused on the determinants of the sectoral structure in advanced economies and the implications of transitioning from an economy dominated by manufacturing to one centred on services.

Before joining Politecnico, I held a postdoctoral position at the Department of Economics at the University of Milan. During this time, I joined the Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano , where I still am a Resident Fellow. During this years of Postdoc I expanded my research interests to international economics, particularly analysing the processes of firms’ internationalisation and innovation activities.

International experiences have been crucial in shaping my academic journey. Toward the end of my PhD, I spent time at the United Nations University – Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (UNU-MERIT), supported by a Marie Curie Visiting Scholarship funded by the European Commission. Later, I worked as a researcher for two years in the Department of Economics at Carlos III University in Madrid within a Marie Curie fellowship programme. My focus was on the role of firms’ internationalisation as a driver of innovation. During this period, I started collaborating with my colleagues which turn to be co-authors of the work I will talk about here on the global production chains

Tell us about your work as an economist at Politecnico di Milano.

A useful starting point for understanding this topic is to highlight the potential broad scope of an economist’s field of research. This includes technology and production, consumption and savings, labour and education, fertility and migration, health and the environment, money and finance, international trade, and public policy. These issues can be studied at the level of countries, economic sectors, individuals, or specific groups. Ultimately, the economist’s work is framed within the overall context of how production and the distribution of resources are structured within an economic system. The aim is to determine whether and under what conditions the well-being of individuals is sustained and, more importantly, how it can be improved.

Within the general field of economics, my focus lies in examining how individual consumption behaviours and corporate decisions influence the sectoral composition of economic systems and drive overall economic growth across countries with different income levels.

The research I am discussing here, in particular, focuses on enterprises and their role within international production networks. I study how decisions related to production, investment, innovation, and internationalisation affect the home country of the enterprise and the other countries connected to it. I also investigate how external factors, such as global economic shocks or policies enacted by national and supranational institutions, shape corporate activities and decisions. My aim is to understand the impact of corporate activities on the current and future economic environment, particularly the resources available to individuals.

Being part of a Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering is particularly meaningful for my research. It enables me to engage with colleagues who examine company activities and decision-making processes from a different viewpoint, typically focusing more on internal operations and decisions made within the company.

Focusing on your recently published study, what is the key area of your research?

In this paper, co-authored with Sergi Basco, Bruno Merlevede, and Martì Mestieri, we explore the effects of the 2008 financial crisis on global supply networks, specifically the international production networks of companies. These businesses are multinational corporations with subsidiaries in countries different from those where their parent company is headquartered. The study focuses on the network of European companies, i.e., firms whose parent companies and subsidiaries are based in Europe, the changes that occurred in the countries where they operated, and the decisions made by the parent companies.

The premise of our analysis is rooted in the potential of multinational production networks to enhance efficiency and foster growth in the economies they span. In line with the principle of comparative advantage, one main pillar of international trade theory, these networks enable more effective utilisation of the specific resources and expertise of individual countries, Additionally, they facilitate the localisation of production closer to markets where goods and services are consumed. As with any complex system, the internationalisation of production—and the networks it relies upon—exhibits significant vulnerability, particularly given the involvement of multiple countries. Furthermore, the benefits of such networks are unevenly distributed among nations, as are the repercussions of adverse shocks. It is crucial to examine the consequences of a negative event like the 2008 financial crisis on these networks and the mechanisms through which these effects were propagated.

What methods and tools do economists use to conduct these studies?

Economists base their analyses on theoretical models and empirical analyses supported by substantial datasets, often drawn from secondary sources. Statistical methods, particularly econometric techniques, are applied to these datasets to identify cause-and-effect relationships in economic phenomena.

For this study, we analysed data from approximately 18,000 European production networks. Each network is identified by a parent company and its subsidiaries across multiple European countries, with information on key metrics such as corporate indebtedness, turnover, productivity, and employment levels. The data for individual companies in our analysis is sourced from the Amadeus database, provided by Bureau van Dijk. Our co-author Merlevede reconstructed the production networks spanning the early 2000s to more recent years. Information on the financial shock was derived from country-level data available through Eurostat. We merged these datasets to create a comprehensive framework, which enabled us to analyse the cause-and-effect relationship between the financial shock and business networks I mentioned earlier.

How did you measure the shock in this study?

We used the risk premia, which measures the difference between a country’s interest rate and Germany’s interest rate. Germany was considered a safe country during the crisis. Therefore, if a country’s risk premia increased, it meant that the country was perceived as less reliable than before.

We examined the period from the summer of 2007 which is considered the starting point of the crisis (in August, BNP Paribas froze funds related to US sub-prime mortgages), to 2012, the year when Mario Draghi, then President of the European Central Bank (ECB), announced the monetary plan to support struggling countries with his famous statement: “Whatever it takes.”

Our analysis of changes in risk premia over this period revealed that many countries became significantly less reliable compared to Germany. Conversely, for some countries, such as the United Kingdom and Denmark, risk premia decreased. For those countries that experienced an increase in risk premia, the debt crisis stemmed from concerns over the country’s ability to repay its debt. We constructed a network-level shock measure by averaging the financial shocks at the country level experienced by the countries where a parent company has subsidiaries. For example, two parent companies based in Germany may be exposed to shocks of significantly different intensities due to the different countries where there subsidiaries are located.

What are the main findings of the study?

Financial shocks, such as the 2008 crisis, underscore the vulnerabilities inherent in the internationalisation of production. Such crises propagate more readily through global production chains. This means that even if a company is in a “strong” country, which is less affected by the financial shock, may still experience adverse effects through its production network. These can influence its performance, employment levels, sales, and turnover. This applies to the parent company, which can be impacted by its network, and the affiliated companies within it.

However, a second, perhaps more significant and less explored aspect, forms the core of our research: a negative shock may prompt the parent company to reorganise its network, altering the number of companies involved, its geographical reach, and the sectors in which it operates. Our findings reveal that financial shocks tend to shrink the size of these networks, reducing the number of affiliates and leading to greater geographical concentration. Not only does the average distance between the parent company and its affiliates decrease, but the affiliates become more clustered geographically. For instance, a German parent company may divest affiliates in Portugal while retaining those in Poland.

The most impacted networks, in terms of growth in the following years, were the international production chains, where the parent company fragmented the production process – sourcing inputs from certain countries, assembling them in others, and selling the final product in other locations. Subsidiaries engaged in a “vertical” relationship with the parent company —handling specific stages of the production process—are more vulnerable to closure than those that replicate the parent company’s business abroad, handling the entire production process and selling final goods in other countries.

Another significant effect is the reduction in turnover and employment for the parent company due to the shock. This result is noteworthy because it occurs even when the parent company is based in a country that was not directly impacted by the financial shock. The second part of our work consists in identifying the channels through which these effects emerge. We observed that the indebtedness levels of parent and affiliated companies are key elements of network fragility. A more heavily indebted parent company is likely to experience greater adverse effects from financial shocks, leading to what I mentioned above. Additionally, affiliates with higher levels of debt, or those operating in sectors more reliant on external credit, are more prone to being divested by the parent company. The study reveals that the negative impact of the crisis on business networks takes place through the disruption of financial relationships between parent companies with their affiliates. The more financially dependent affiliates are on the parent company, the more fragile the network becomes, increasing the likelihood that affiliates will be excluded from the network during a crisis-induced reorganisation. This is particularly evident in vertical networks, where the production relationships between companies naturally lead to financial flows between the parent company and its affiliates.

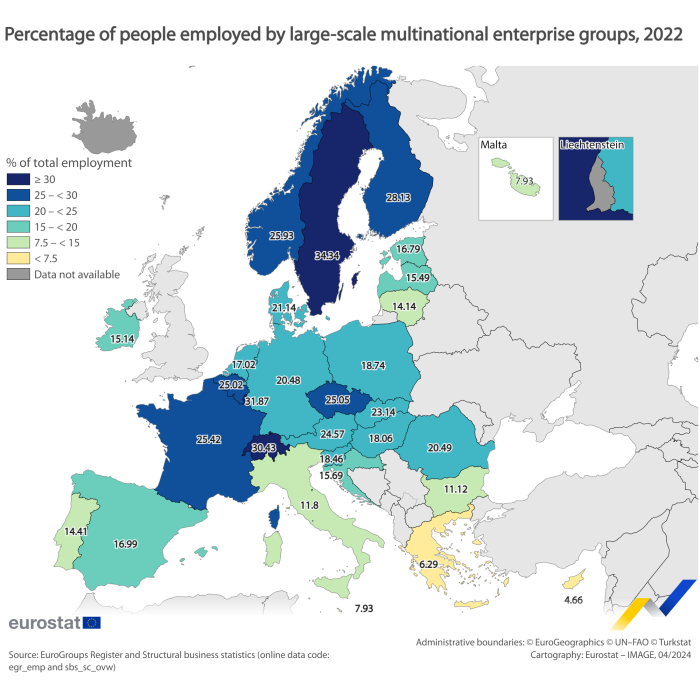

Finally, the geographical location of firms plays a crucial role in conveying the shock’s effect. In Europe, multinationals—despite their importance in terms of employment and production—are relatively few and parent companies are concentrated in only a handful of countries, typically northern Europe. Our research demonstrates that subsidiaries in Mediterranean countries, particularly those most affected by the financial crisis—commonly referred to as PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain)—were disproportionately removed from networks. This was not necessarily due to inefficiencies on their part, but because of the financial ties they had with the parent company.

What are the implications of this study?

As previously mentioned, our study is based on the premise that international production networks can play a beneficial role in the global economy. Therefore, it is crucial to identify their potential vulnerabilities and the redistributive implications.

One of the key messages from our research is the critical importance of a healthy and efficient financial system. This must direct resources to efficient enterprises and provide support during times of crisis. This reduces financial dependence on parent companies. However, the financial markets in Europe are not sufficiently integrated, which undermines the ability of the financial system to perform its role effectively. This has become a widely debated issue across Europe. A more integrated European financial system would bolster production chains, enhance the competitiveness of European businesses, while reducing the dependence of certain countries on resource reallocation, and, as a result, strengthen their economies.

Our study highlights the inherent asymmetry between parent companies and subsidiaries in the decision-making process, and the implications of this imbalance during a crisis. This highlights the importance of complementing a country’s capacity to attract foreign investment, with strategies to develop resources and technologies that empower domestic companies to expand and invest globally. An efficient and integrated financial system should support businesses in this endeavour. Moreover, European industrial policy could play a pivotal role in identifying and nurturing country-specific opportunities for growth and innovation.

Why is it important to study the 2008 financial crisis?

Financial crises come in many forms: no two crises are identical, yet their negative effects tend to be medium- to long-term, impacting businesses and households. Reduced access to credit leads to a fall in production for businesses and a decline in demand for households. The decisions made by multinationals during crises impact production and employment and have far-reaching socio-economic consequences. By studying past crises, understanding their mechanisms, and identifying the channels through which they exert influence, we can better prepare for future crises.

The 2008 financial crisis is particularly important because it marked a turning point: the world that emerged afterward was fundamentally different. Relations between firms, international trade, and global economic growth underwent profound changes. The financial shock of 2008 reshaped production networks, and this reorganisation was not temporary. It remained evident in the years that followed, particularly between 2013 and 2015. The 2008 crisis marked a turning point—a moment of disruption that initiated an ongoing process of reorganisation. This process continues in response to the continuous waves of global shocks, each of which presents challenges, particularly regarding the international integration of markets and production systems.

What will your research focus on in the future?

I intend to focus on another critical aspect of international European networks – innovation. There is increasing concern about the loss of competitiveness among European firms, particularly in manufacturing sectors, as Europe struggles to remain at the forefront of innovation.

The aim of the next study is to examine how the 2008 financial crisis affected the innovative capacity of firms within international production networks. At this early brainstorming stage, the key question we hope to answer is whether the innovative capacity of an international network of firms exceeds that of a national network, which in turn is greater than the sum of the effort of individual firms operating in isolation. Although there is little empirical evidence on the relationship between international networks and innovation, existing literature suggests there may be a positive connection. First, international networks can exploit the excellence of firms located in different countries, each possessing distinct capabilities, technological specialisations, and unique national innovation systems. A network of companies should foster more innovation than individual companies. Second, we must consider the international transmission of knowledge, or knowledge flows. A parent company, which is better equipped to face the costs of research and development, can transfer knowledge by partnering with production firms in different countries. This facilitates the international spread of innovation while minimising the financial burden on the affiliated companies. However, it is essential to understand which network and environmental features ensure the effective transmission of knowledge, and who benefits from this knowledge transfer.

Another aspect we will explore is how innovation capacity depends on financing. Once again, the financial system plays a key role, as innovation requires significant investment.