We met with Francesco Braghin from the Department of Mechanical Engineering. He is director of the interdepartmental laboratory E⁴SPORT, six departments from the Politecnico serving athletes and people with disabilities.

Speaking with him, we understood not only how important it is to work together, but also that the passion we put into our work is fundamental and that it can be very satisfying.

For nearly ten years, E⁴SPORT has conducted research in the field of sport. What is the idea underlying your creation?

At the beginning, each of us researchers already conducted independent activities in sport.

At a certain point, we realised that the challenges and requests that were presented to us could not be solved just with our individual skills alone. Which is why we started to work together well before the official launch of the E⁴SPORT interdepartmental laboratory. The idea of joining together stemmed from our frequent meetings and sharing problems that fell under our respective areas of expertise. In short, we became a team.

What are the components of E⁴SPORT?

Six university departments form part of the laboratory. Marco Tarabini and I come from the Department of Mechanical Engineering, and I am the current director. Manuela Galli comes from the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering; Stefano Mariani is from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Emanuele Lettieri from the Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering, Luca Andena and Tomaso Villa from the ‘Giulio Natta’ Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering; and Giuseppe Andreoni is from the Department of Design.

Let’s take a step backwards. What were the first steps in forming E⁴SPORT?

I first contacted Manuela Galli about a biomechanics problem. Bobsleighs are accelerated by the athletes in the initial section of the track (initial push) and the secret lies in finding the right moment to jump on. If they miss it by a second, either they can’t accelerate the bobsleigh as much as possible or they risk slowing it down. And this moment depends on the athlete’s anthropometric leverage. So, as always in professional sport, the equipment (bobsleigh) is designed for the athlete.

And how did this bobsleigh study end?

It was a two-person bobsleigh. We realised that by ourselves, we could even have designed the bobsleigh better from the ground up, as if it were a Formula One car, with the best dynamics and aerodynamics possible. But in the end, the bobsleigh wins if it starts well. If it doesn’t come in first, it was probably because it started badly, because the athletes got the push wrong, because they jumped on badly, etc.

So you also have to see how the athlete jumps onto the bobsleigh.

At this point, we were fully aware that we could not have solved many problems alone. This led to the desire to take advantage of the interdepartmental laboratories and pool our expertise.

What are the goals?

E⁴SPORT has three main objectives.

The first is to bring the larger public to sport, because sport certainly contributes to reaching a certain age in good health. So the events we organise also serve as promotion, to make people aware of the importance of sport. For the larger public, there is no need for advanced technology, but it is essential that they understand that, despite the effort, sport makes you have fun in the end. It activates endorphins. You make an effort, you finish tired, but you’re happy.

The second objective?

To bring sport to young people with disabilities and help them participate in it. Sport, which should help us to socialise, like in team sports, is instead a barrier for some people, those with motor difficulties, for example. At such times, they feel excluded. Instead of bringing them together, sports pushes them away. Precisely against the sporting spirit. And so that they can participate, each person needs specific assistance. Perceiving the idea ‘I move just like everyone else’ is essential.

The last objective …

Is professional sports. Since performance is taken to the extreme, it is important that the athlete ‘wears’ the equipment. We know that a person feels good with specific shoes, skis, skates, helmet, or tracksuit.

So even for professional sports, it is important to personalise the equipment for performance. Or speaking about disabilities once again, for integration and inclusion. So we need to study sports equipment and the way it interacts with the athlete’s movement, so that it is specific and leads to the desired performance, or even exceeds it. There is not just the form, material, movement. Each aspect works together, leading to the result, which in one case may be inclusion and in another, performance.

This is why we find ourselves working together, standardising our instrumentation, because otherwise we cannot bridge the gap that leads to inclusion and/or victory.

How did the collaboration evolve among yourselves? Could you give us a summary?

In reality, we found ourselves among friends. Maybe it is also the sporting spirit that unites us and makes us feel like friends rather than colleagues, or not just colleagues. Today, we know ourselves and each other’s expertise so if we have any sort of problem, we know whom to call.

Can you give me an example?

Through Fondazione Politecnico, we were contacted by a company that makes bases for five-a-side football pitches. We helped them design a base with better performance than the competition. In the end we ran into a problem with the materials. So I contacted Luca Andena (I call him for any problem related to materials; he’s my reference now).

Just like Stefano Mariani is my reference for simulations. For the athlete’s gestures, movements, who do I call? Manuela! And so on.

Basically, as I was saying before, our relationship has become an all-round friendship.

There is always an opportunity to call each other and say: ‘You, who know my specific problem better than I do, can you give me some advice?’

Which cross-cutting skills have been most successful for production? In which projects?

The helmet studied under Stefano Mariani’s project ‘Safer Helmets’ was certainly one of them. This project also had different goals.

The first was to increase people’s awareness, especially among young people, about risks tied to certain speed sports.

Then we wanted to develop a monitoring system included in the helmet to support rescuers in the event of a fall or impact.

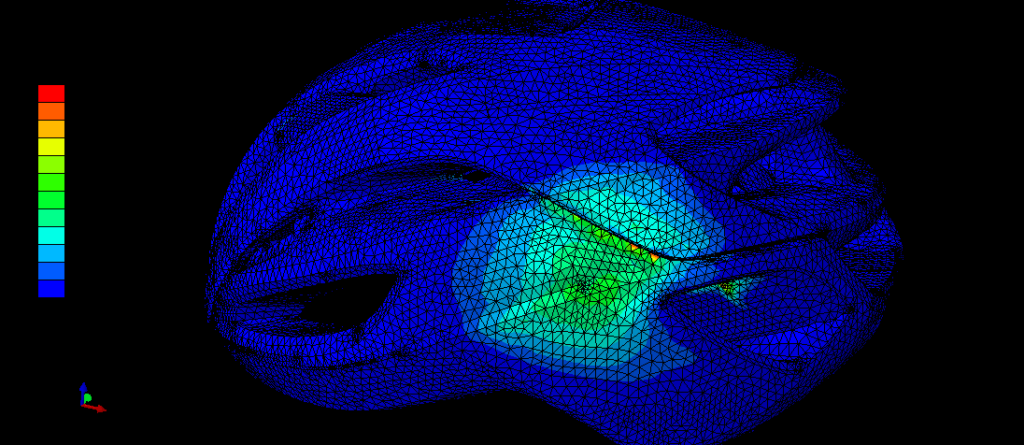

We concentrated on cycling and Alpine skiing due to the similarity between the two sports in terms of speed, exposure to the risk of falling, and helmet construction. We considered the correlations between the different points of cranial impact and effects in terms of concussions.

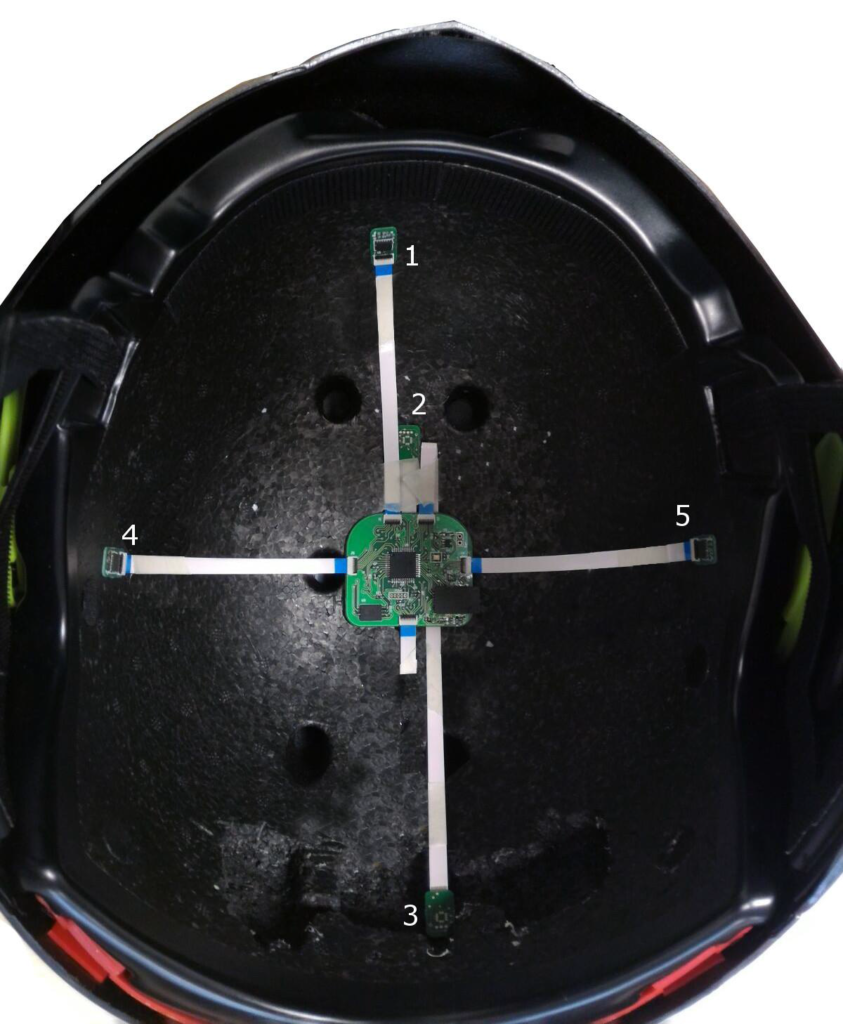

Then we built and tested a prototype for a helmet equipped with an array of micro sensors to perceive impacts at the most probable points according to medical research. MEMS (micro-electro-mechanical systems) were used due to their light weight and minimal invasiveness, to avoid reducing the protection guaranteed by the helmet.

In collaboration with an important helmet producer in Lombardy, we then developed an integral model for the polymer foam used as an internal layer in the helmets. Then we implemented a model that could gather the combined effects of the impact and helmet geometry, creating a sort of digital twin of the helmet, which was tested and calibrated in the lab.

Another example of collaboration in sport?

Another example is the project by Luca Andena, who has worked for more than eight years with Mondo S.p.A., a leader in the production of sports surfaces, to develop advanced athletics tracks.

The collaboration concentrated on the use of a simulation to combine traditional design based on prototypes with virtual modelling.

The structure of a prefabricated athletics track is complex. The material must be chosen carefully, identifying the best compromise, that is, absorbing enough energy to prevent injuries for athletes and reduce strain on the joints, but also supporting the athlete’s movements so that the energy is returned to the athlete at the right time and in the right way to maximise performance.

What were the practical results?

The study led to the selection of an elliptical honeycomb used for the track in the Stade de France and the definition of a new model of track: Mondotrack™Ellipse Impulse.

With the new subfloor design, the track responds fluidly and dynamically to every step, leap, or throw, significantly improving the absorption and return of energy transmitted by the athlete to the track.

Beyond industrial success, which project has given you the most satisfaction?

Oh, after bobsleigh, I’m a huge fan of winter sports. I have followed projects for skiing, luge, skeleton, etc.

I remember when we first had Armin Zoeggeler, who is now at the end of his career (we’re talking some years after Cesana), try titanium runners. Following our analysis, the thermal conductivity of titanium was ideal for minimising friction between the runners and the ice. And in effect, his time was incredible. Unfortunately, the runner material is set by the Federation and so titanium runners were not permitted at all.

What happened?

I’m going by memory, because this was a few years ago … Armin’s run times on the track at Cesana were 51–52 seconds. With those runners we reduced the run time by more than a second. Keep in mind that people win or lose by a hundredth of a second (the top three are typically all within a second), so this is something unbelievable …

It was a huge satisfaction. It meant that the model had got us. We had understood the mechanism that leads to friction between the runners and the ice.

Then there was also the skeleton, right?

Yes. Based on Maurizio Oioli’s indications, we redesigned the sled to facilitate certain movements (basically greater torsion of the sled). And with that sled, Maurizio had his best position in his World Cup career: 9th place at Lake Placid (USA). These are great satisfaction!

To conclude, could you give us a message that summarises your work with E⁴SPORT?

In my opinion, using technology for sport is the beauty of research. You do it for the passion, for the people of your country, you do it for the enthusiasm that you see in these people, which should also be our enthusiasm.