In a hyper-connected society such as ours, popular science plays an increasingly important role in communicating the results of research to the widest possible audience. For this reason, public engagement—in other words all those non-profit activities with an educational, cultural and social development value—is part of the Italian university’s third mission.

It is also what we try to do with Frontiere, the publication that you are reading. However, popular science is not new here at the Politecnico: even in our early years we had a surprising teacher, Antonio Stoppani, our professor of geology from 1862 to 1878. He was a special figure with liberal ideas who combined the roles of scientist, scholar and man of the cloth.

In particular for those from Milan, Stoppani’s image should be familiar: it is his statute that watches over the Natural History Museum in the Indro Montanelli public gardens. We will soon understand why.

An adventurous life

Antonio Stoppani was born in Lecco in 1824 as one of 14 siblings. He was extremely curious from a young age: he often ran away, catching insects and butterflies and always came home laden with rocks. He was fascinated by nature and minerals in particular. When he was older, he discovered by chance that what he thought to be an ordinary collection of stones was in fact extremely valuable.

In 1848 he took part in the Spring of Nations: during the Five Days of Milan, he communicated with the rebels behind enemy lines through small hot air balloons that had been ingeniously constructed for this purpose.

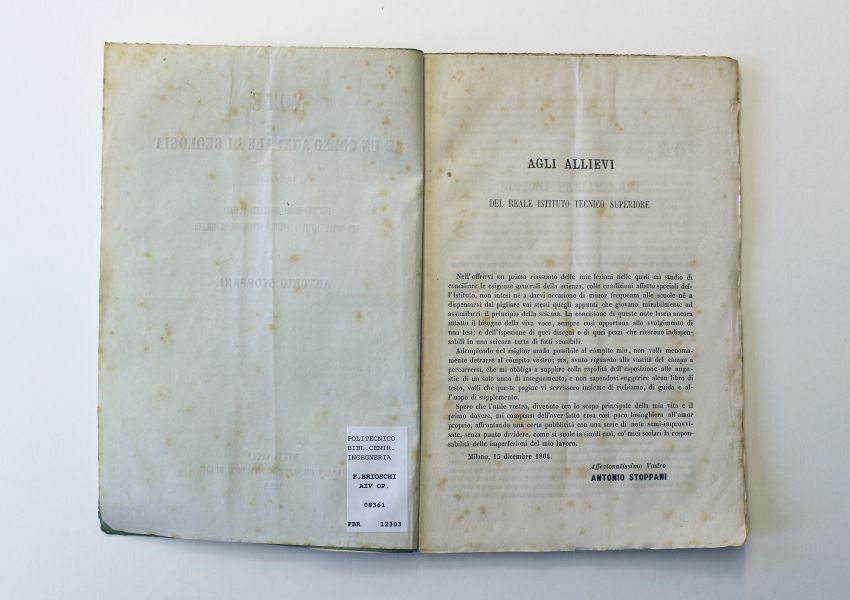

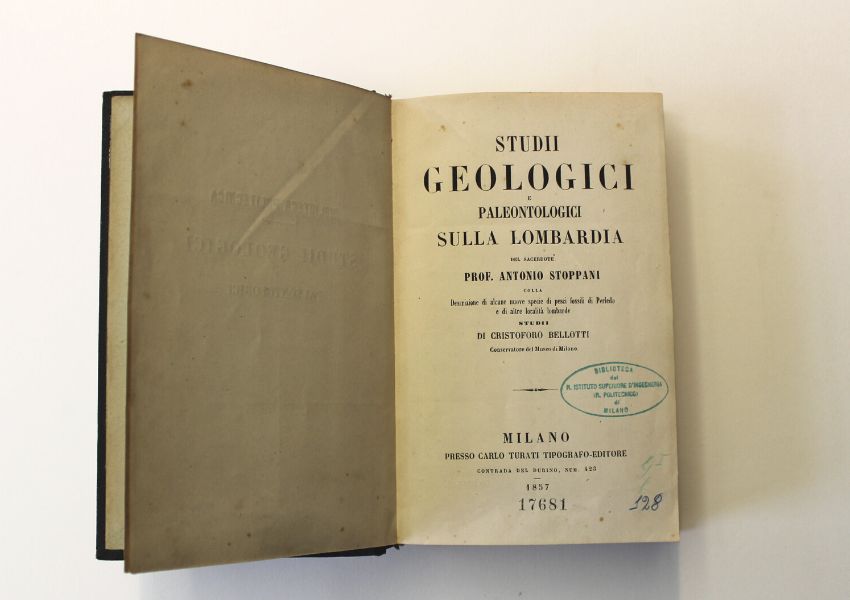

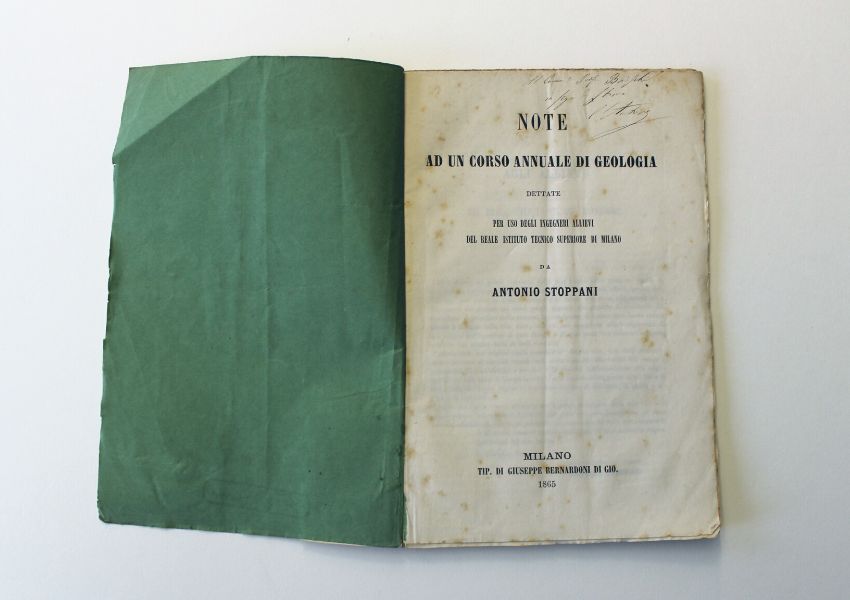

He began his academic career as thethe first Italian professor of geology at the University of Pavia in 1861-62. In 1862, he became a professor at the Istituto Tecnico Superiore di Milano, which would subsequently become the Politecnico di Milano. It was Stoppani that invented stratigraphy, and his three-volume annual course in geology (1866-70) was universally admired for its style and clarity. In this work he introduced the concept of the “Anthropozoic era” in which mankind had begun to have an impact on nature.

He remained with us until 1878, before returning in 1883 after a period of work in Florence. In 1875 he became a member of the Accademia dei Lincei.

Stoppani as a popular scientist

Stoppani was both a man of letters and a scientist. He represented a new kind of intellectual who worked in many fields: a populariser, a political figure (he ran for the position of mayor of Milan) and a university professor at the Politecnico.

For many reasons, we can regard him as one of the country’s first popularisers of science in his own right. His concept of culture was extraordinarily modern and democratic. In his opinion, scientific ideas needed to become cultural heritage for everyone. He was an advocate for improving the average level of education, believing it to be a fundamental part of collective wellbeing.

Director of the Natural History Museum in Milan

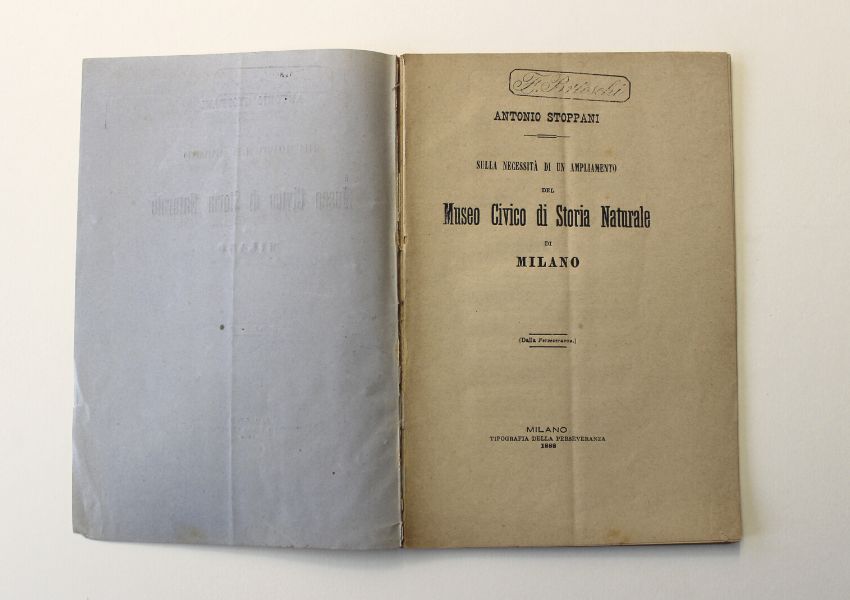

In 1882, Stoppani became director of the Natural History Museum in Milan.

He immediately donated all of his naturalist collections to the museum. He developed an impressive, modern way of talking about science: he created dioramas for example, genuine stages on which scientific information could be exhibited and become a show.

He stressed the need for a new building, which was designed by a student of his from the Politecnico, the architect Giovanni Ceruti. The works were made possible by funds provided by from private individuals following an intense fund-raising campaign put in place by the abbot. The end result was the biggest museum of natural history in Italy and one of the most prestigious in Europe.

Unfortunately, Stoppani would not see the birth of his “baby” as he would die before it opened.

Lectures

In order to address an ever-widening audience, he delivered many scientific lectures aimed at citizens, which were held at the Salone in the Porta Venezia public gardens, precisely where the monument to him is now found.

At that time in Italy, lectures were a widespread cultural event: they were held in infant schools, secondary schools and colleges, universities and academies, museums, public and private clubs, cultural societies and associations, and at theatres. The talks were given by skilled orators and were often followed by experiments and demonstrations which captivated the audience. They were either enjoyed in person or subsequently available in printed form.

Stoppani was an extremely talented public speak who had extraordinary charisma and, with a vice for caressing his thick white hair, he fascinated the ladies that fought over tickets to listen to him. Indeed, tickets for his lectures were perpetually sold out.

They like his rich and eloquent speech; that handsome, round face and refined smile of his, both witty and kind; that thick, grey hair which is graciously tossed around by the passion of his speech; that harmonious, suggestive voice; those calm eyes, which are always fixed above the heads of the audience.

his friend Maria Alinda Bonacci Brunamonti would remember.

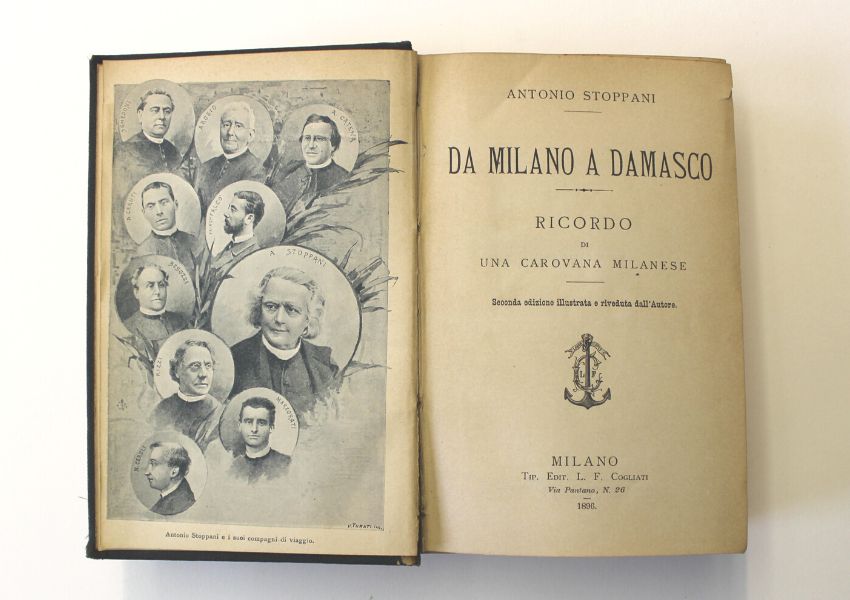

Travels

Stoppani also travelled extensively throughout his life, and in particular he retells these journeys in his works, such as “Il Bel Paese” (“The Beautiful Country”), about which we will talk later, and “Da Milano a Damasco” (“From Milan to Damascus”) (1888). He introduced study holidays to his university courses and, in his capacity as president of the Lombardy section of the Club Alpino Italiano, he organised parties of 10-15 people which were tasked with discovering the most interesting places in Italy from a geological point of view.

Il bel paese

“Il Bel Paese” is the title of the book that made Stoppani universally famous. The first edition of this Italian classic of popular science literature was published in 1876. The book became part of the literary pantheon that contributed to “making Italians”, after having made Italy, to quote D’Azeglio.

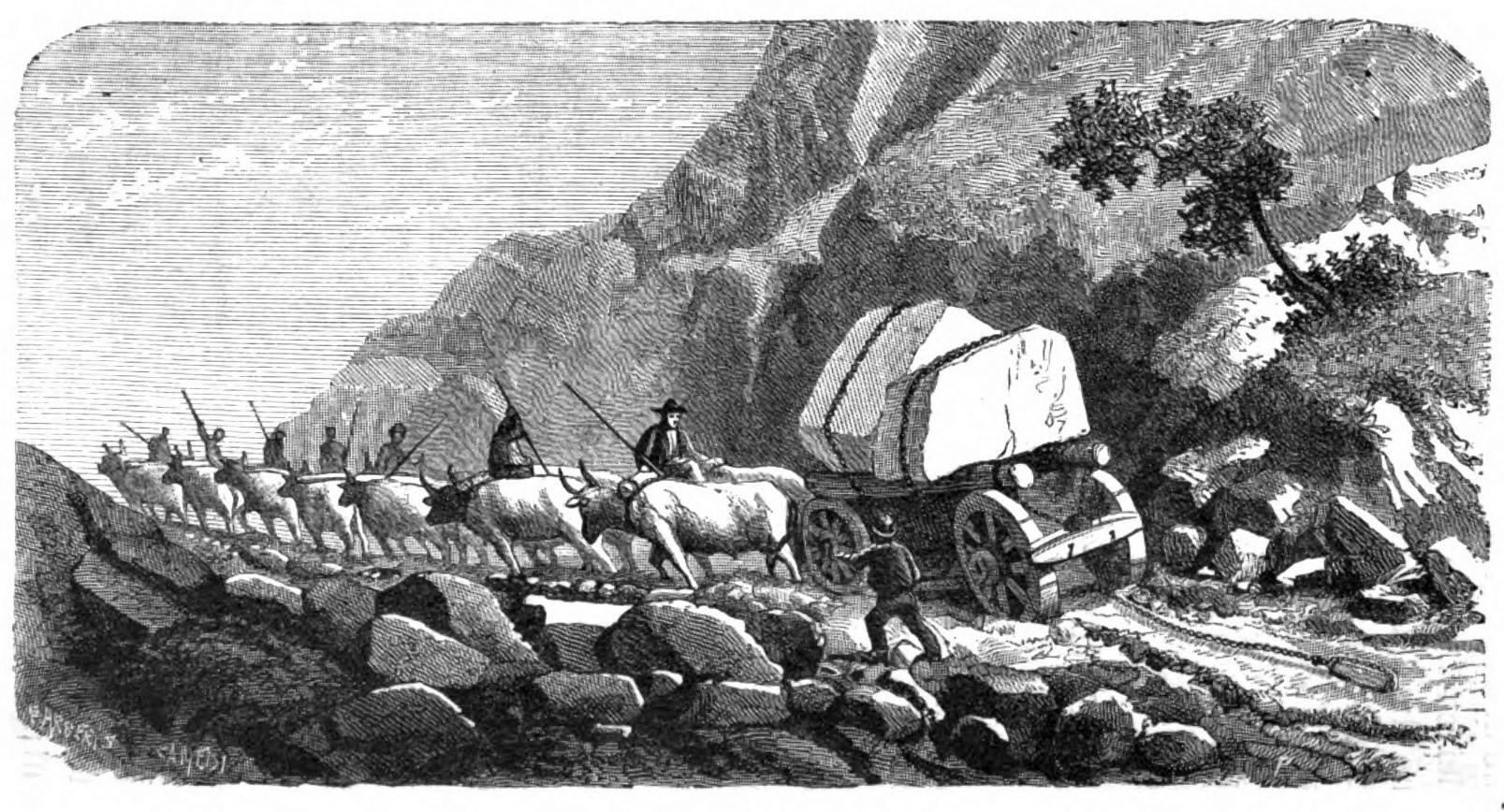

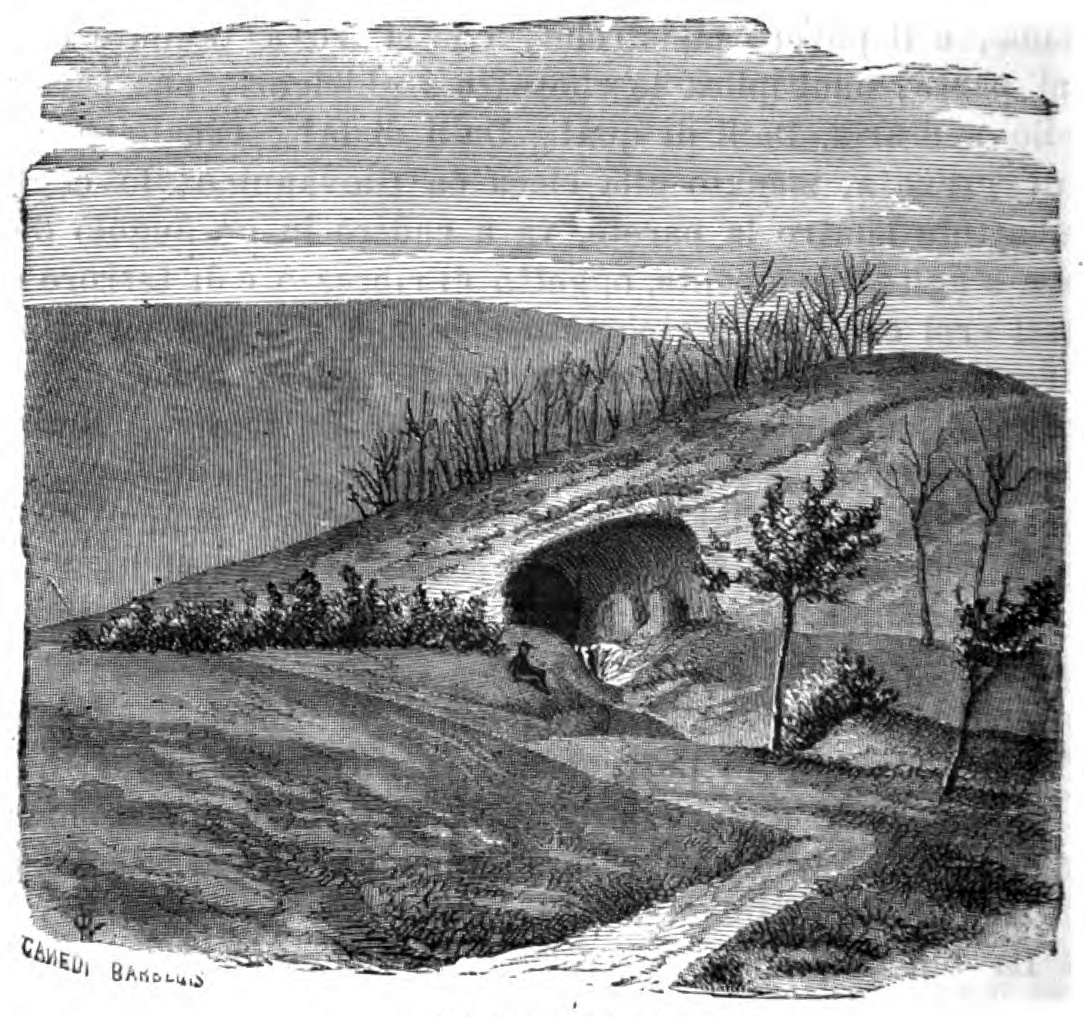

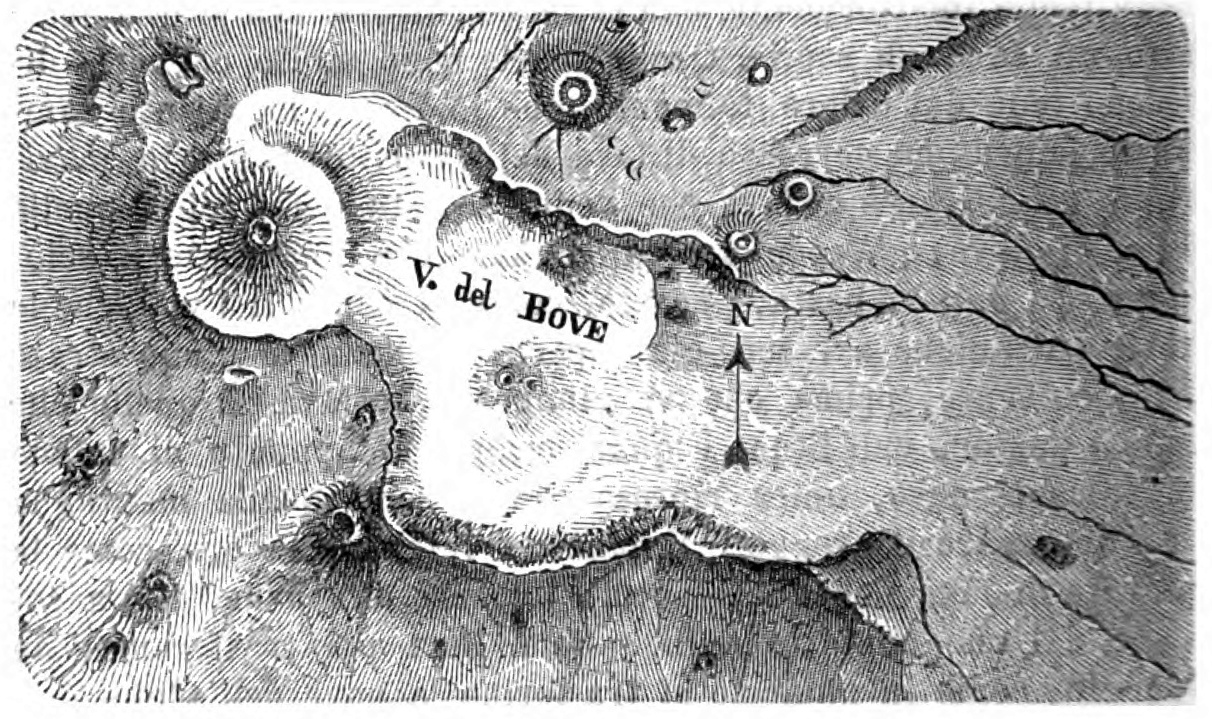

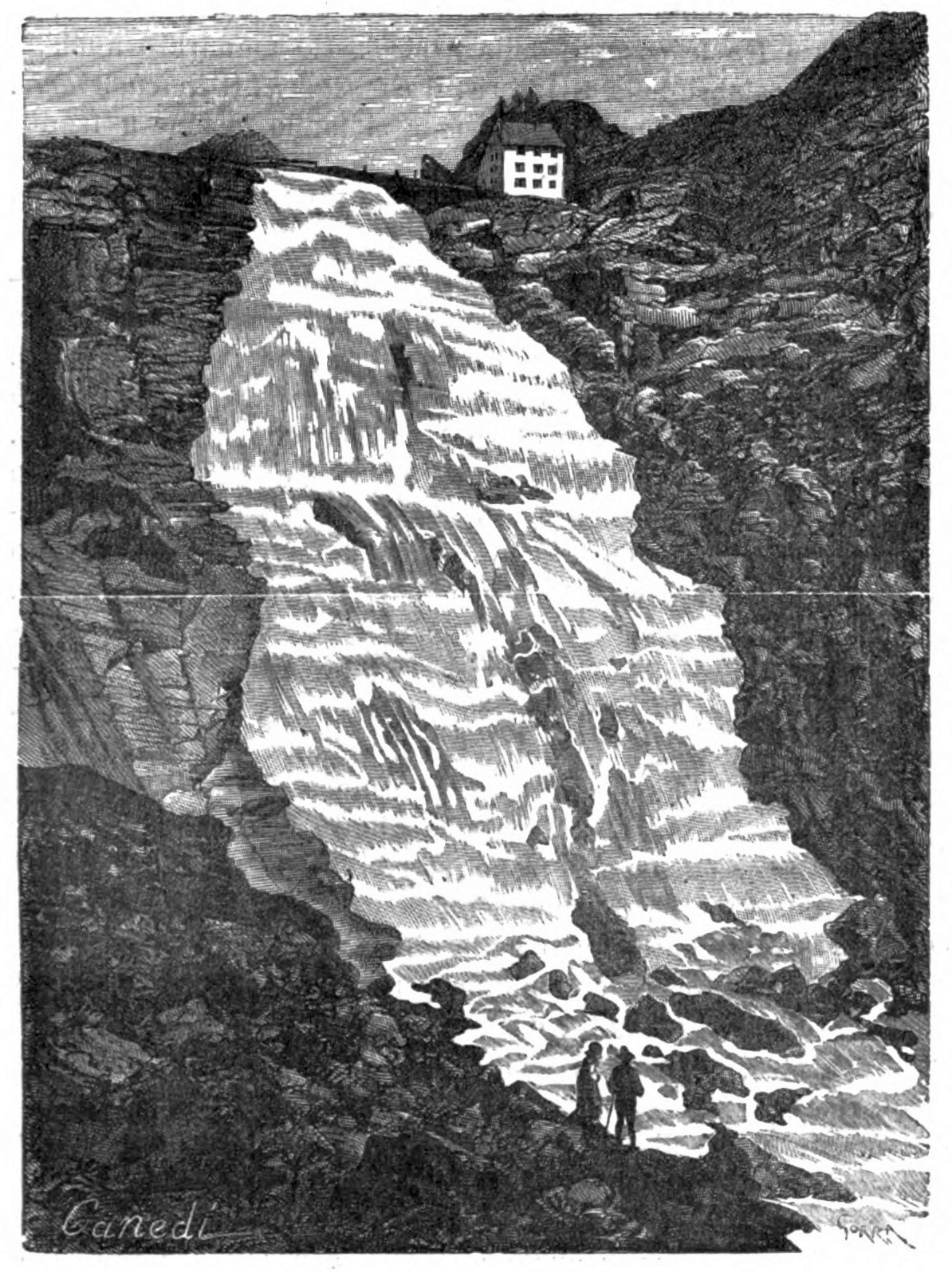

The success of this work was due to how it addressed its topic, rather than the topic itself. The book follows Stoppani’s naturalist expeditions through Italy, which are arranged into an ideal journey from the Alps to Sicily, throughout which the minerals, flora and fauna are studied. But how did he develop this idea?

By making the scientist a narrator. Stoppani therefore embodies an uncle who every Thursday (a day off from school) relates his travels to his nieces and nephews about over 29 weeks, across as many chapters.

Weaving science and aestheticism, he described the lay of the land, but also its natural beauty.

We find ourselves in Milan, in the family environment of a sitting room of a private house with windows through which the Virgin Mary can be seen atop the Duomo. The purpose is to intrigue and thrill the listeners (within the fiction) and therefore the readers (in reality), creating complicity with the audience. The uncle is at heart of the scene, prompting warmth and trust. Around him are children, their parents and other acquaintances.

This is a useful narrative-dialogue device; a formula which is particularly effective because those listening to the words of the uncle are many and varied, creating a community that the scientist addresses while taking into account their different levels of knowledge. The language and setting are intended for a young audience. The real protagonist is the topic of the lecture. The narrative fiction serves the scientific description.

“Il Bel Paese” is extremely versatile: it can be read aloud to the family or by older readers on their own. It was adopted by schools in the kingdom and it lent itself to being used across the whole country. The chapters stand alone; they can be read in any order.

The work encompasses many genres: primarily it is a work of popular science, but it is also travel literature, an illustrated book and kind of tourist guide, because it even provides practical information abouts inns and hostels.

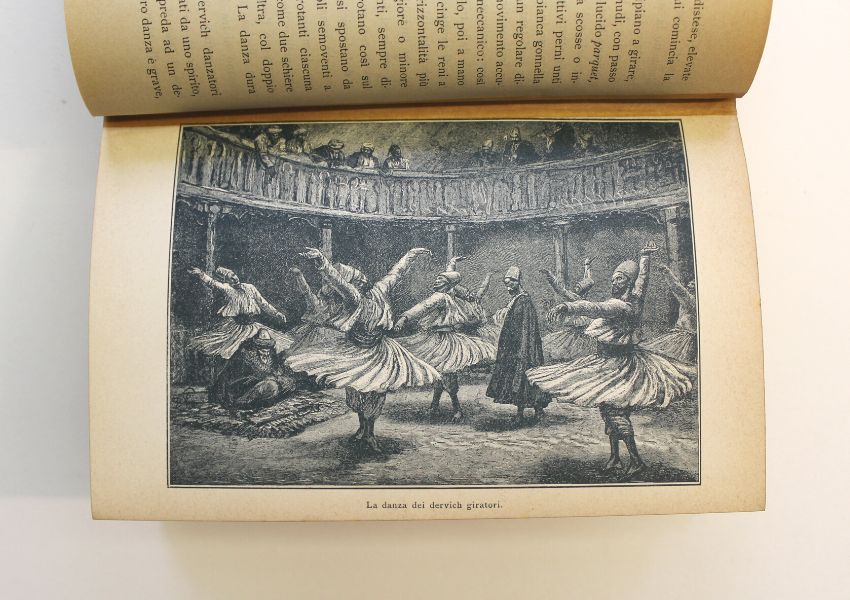

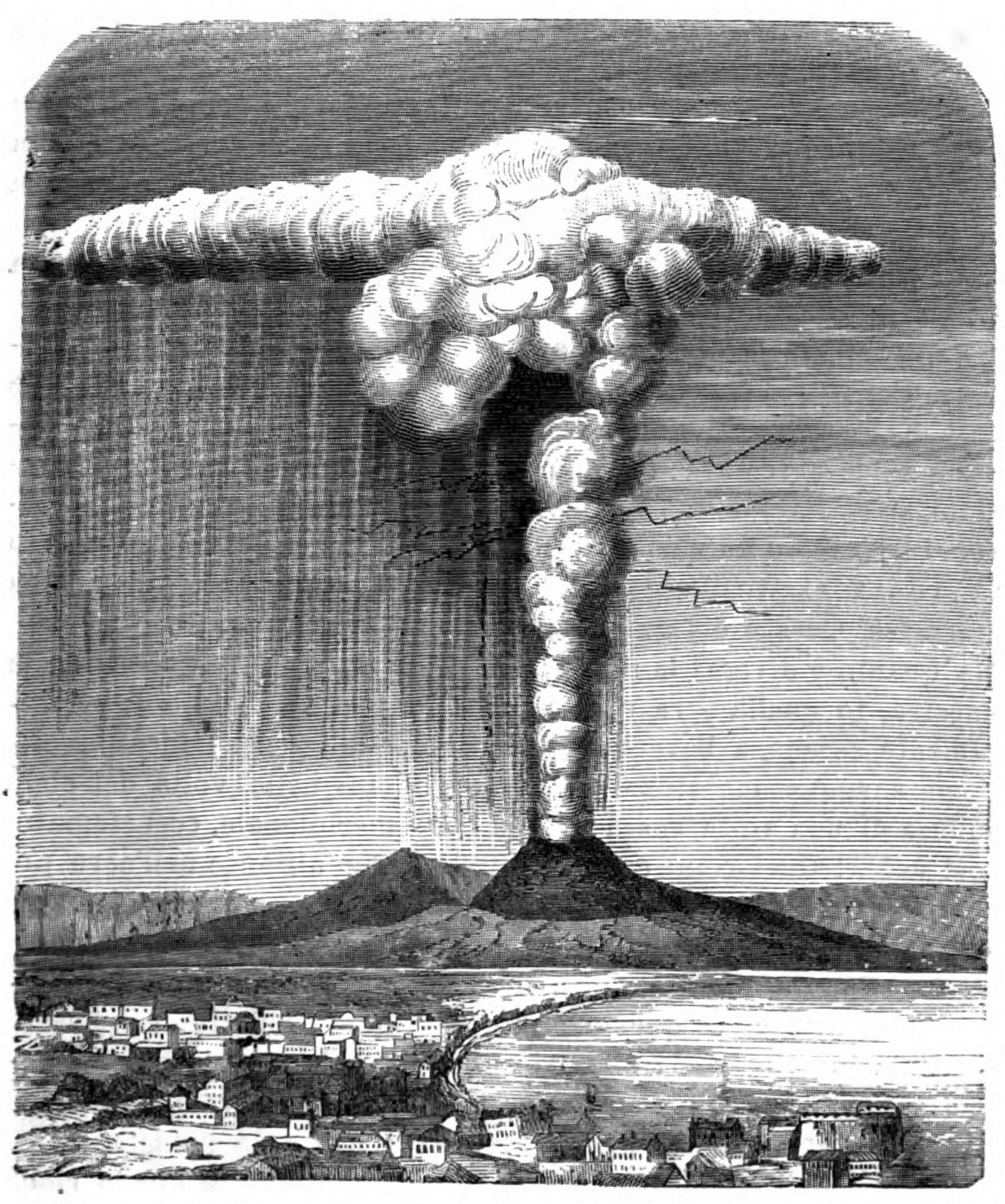

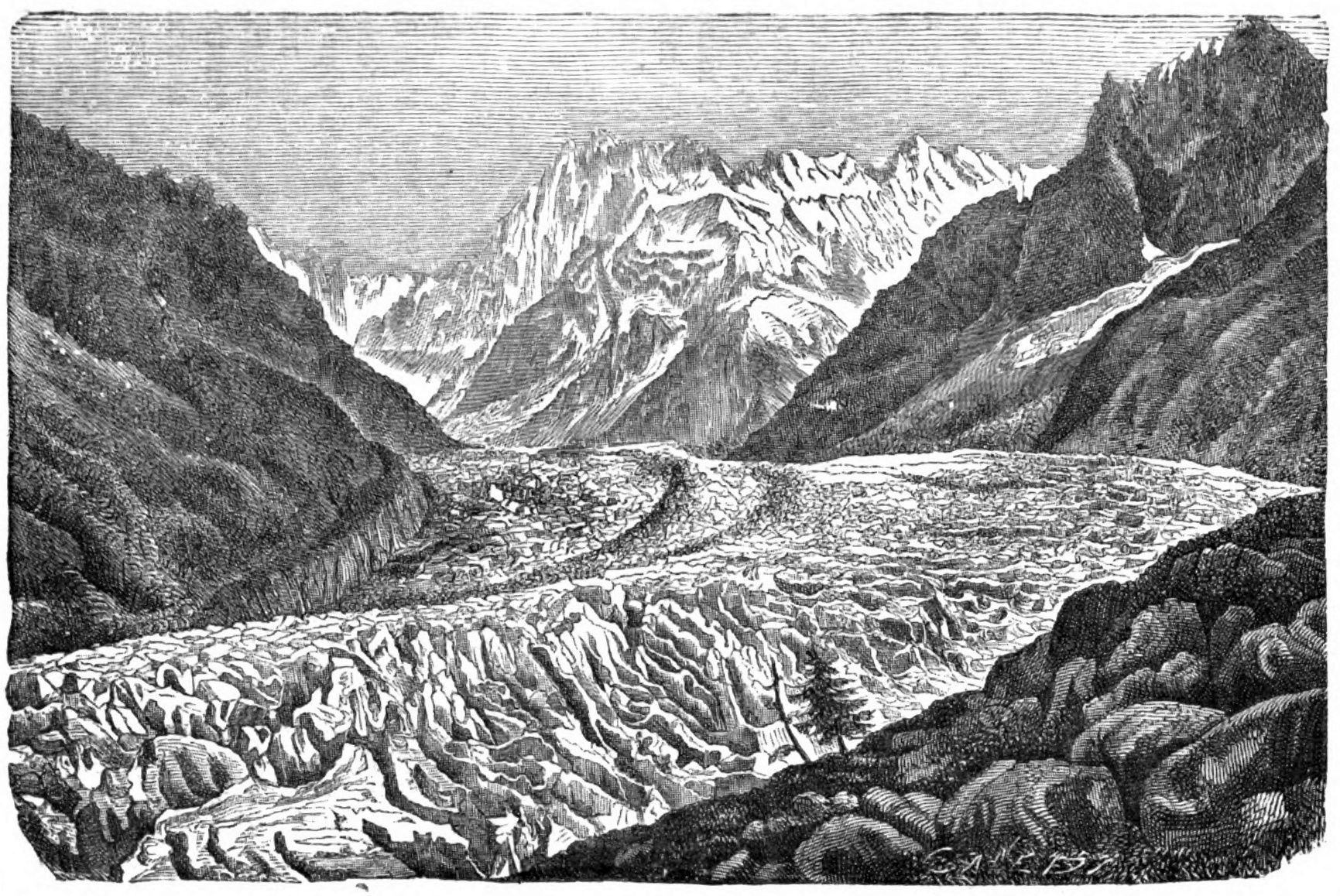

The illustrations are a fundamental part of the work’s vision. The images begin to take on their own meaning and are designed to impress the reader. There are topographical images, conventional reproductions of areas, naturalist images of animals and plants, landscapes that represent the power of nature, with a study in the sublime of romantic taste.

Ultimately, “Il Bel Paese” was a modern, original and well-designed book. We can define its novelty as “popular experimentalism”, because it modernised scientific communication by directing it to the widest possible audience. Indeed, the author was the first to take into consideration the audience of young children in a united Italy, providing a precursor for children’s literature.

Winning many awards, Stoppani’s “Bel Paese” would enjoy enormous success, becoming both a best-seller and a “long-seller”, remaining in print from 1876 until the 1950s. In the 1904 sales charts, more than thirty years after its release, it ranked just behind the untouchable “Promessi Sposi” (“The Betrothed”), “Cuore” (“Heart”) and Pinocchio.

In the same period, the immense popularity of the work in the collective imagination gave rise to Egidio Galbani’s unprecedented marketing campaign, choosing the name for a new cheese he had invented and putting the abbot’s image on his packaging.

Death

In the later years of his life, Stoppani faced increasingly bitter criticism from certain catholic quarters for his positivist vision and his comments on the relationship between science and faith. He took the newspaper “L’Osservatore cattolico” to court for having reached the level of defamation.

He died in 1891, shortly before the inauguration of “his” Natural History Museum. The entire city stood still, as we can read in the report of his funeral from the Corriere della Sera on 6 January 1891.

There were not only funeral proceedings, but a solemn demonstration in which the various classes and political divisions of the entire citizenry took part, except for the extreme clerical hard-liners, or at least the ringleaders, who had the decency not to attend. […] Not since the funeral of Ponchielli – who was so popular in Milan – had anything so striking been seen.

from “Il Corriere della Sera” on 6 January 1891

For those wishing to learn more, we recommend two texts. The first, more general, explores the figure of Stoppani and the other popularizers of his time: by Luca Clerici, “Libri per tutti. L’Italia della divulgazione dall’Unità al nuovo secolo” (Laterza, 2018). The second analyzes the publishing phenomenon of the Bel Paese: edited by Pietro Redondi, “Un best-seller per l’Italia unita. Il Bel Paese di Antonio Stoppani” (Guerini e associati, 2012).

You can find a free digital copy of “Il Bel Paese”, in its first edition of 1876 printed by the publisher Agnelli of Milan, on the British Library website.

In the Historical Library of the Politecnico di Milano, however, you can find a more recent copy, attested between 1920 and 1922, as well as several other works by Stoppani.