Until recently, Amuchina was an everyday product commonly used for cleaning household surfaces or sanitising laundry. A name so deeply rooted in our lives that it even lost its reference to the brand itself, becoming a genericised trademark that refers to any disinfectant used in the home.

Nobody could have imagined that last year, this product – whose history and origins most of us have never even considered – would have come to enjoy a new and unexpected wave of success, becoming a feature of our everyday lives in the form of hand sanitiser.

The Politecnico di Milano also played a role in this long history. Indeed, with a visit to our own Historical Archives, we can even find the document which we could say marked the start of all this.

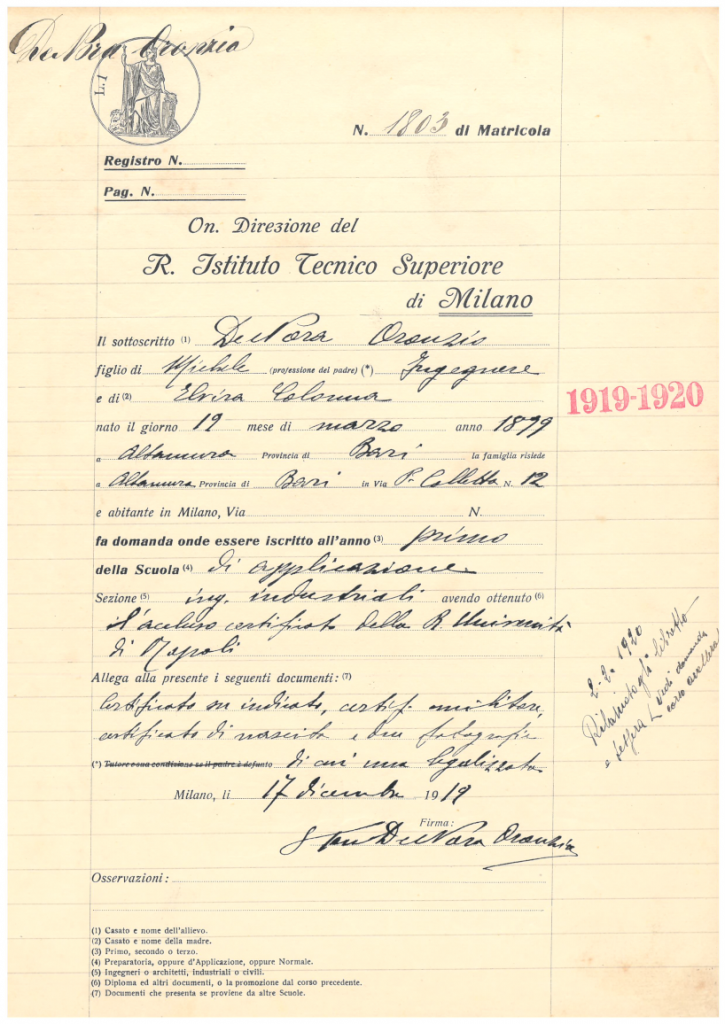

An old sheet of ruled paper, yellowed by time, tells us that it was December 1919 when Oronzio De Nora, a young student of Puglian origin, applied to enrol in the first year of the Industrial Engineering section of the School of Application.

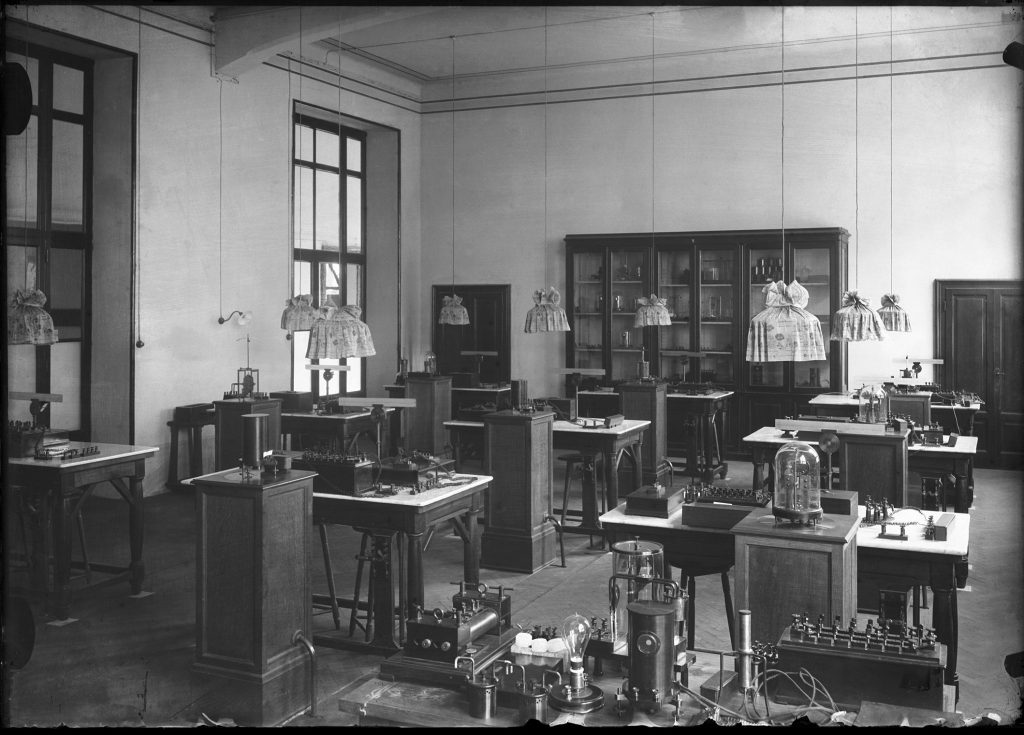

Back then, we were still known as the “Regio Istituto Tecnico Superiore di Milano” and our home was in Piazza Cavour, in the now-demolished Palazzo della Canonica, where we now find via del Vecchio Politecnico. These were pioneering times for chemical laboratories: at first, the university made use of those of the Society for the Promotion of Arts and Trades and the School of Agriculture, and it was only in 1920 that a small temporary laboratory for general chemistry practice was set up by adapting an enclosed portico on the first floor of the Palazzo.

There is a legend surrounding the invention of Amuchina. In 1922, De Nora was working on his thesis on the electrolysis of chlor-alkalis. One day, whilst working on an electrolytic cell in the laboratory, he injured his hand. The electrolyte being used at the time was salt and water and, being aware of the disinfecting properties of the solution, he immersed his hand in it before bandaging it up. That evening, when he removed the bandage, he realised that the wound had already healed. His father also served as a ‘guinea pig’: once he received a package of the solution in Bari, he experimented with it by gargling it during a bout of tonsillitis, and the pain disappeared. Hence Oronzio De Nora’s insight into the use of sodium hypochlorite as a disinfectant and healing agent.

After graduating with a degree in Electrotechnical Engineering, in 1923 – at the age of just 24 – he filed the patent for the production of sodium hypochlorite, marking the start of his success. The aqueous solution of the compound, in various concentrations depending on the intended use, proved to be a potent, fast-acting, broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent. De Nora named it Amuchina, inspired by the Greek word for a scratch or abrasion. In 1924, he founded Industrie De Nora, becoming a pioneer in the construction of facilities for the production of chlorine and caustic soda.

Since then, Amuchina has been in constant use, but has periodically returned to the spotlight for various reasons. In the 1930s, it was mainly used to combat tuberculosis. During World War II, meanwhile, it was used to disinfect drinking water. Between 1950 and 1980, it became the most widely used product in hospitals for disinfecting dialysis machines. In the 1980s, following the cholera epidemic in southern Italy, it became the most commonly used disinfectant for drinking water, fruit and vegetables.

In 2020, nearly 100 years after its debut on the market, another health crisis – what we now know as COVID-19 – hit Italy and the whole world. Health authorities deem constant hand sanitisation to be essential to limiting the spread of the virus, resulting in small bottles of Amuchina cropping up everywhere, this time using a formulation based on ethanol and glycerol, which has an advantage compared to sodium hypochlorite in that it is not aggressive to the skin. But in the first few months of the crisis, shops were hit by stampedes, stocks quickly ran dry, and the prices of the precious liquid skyrocketed.

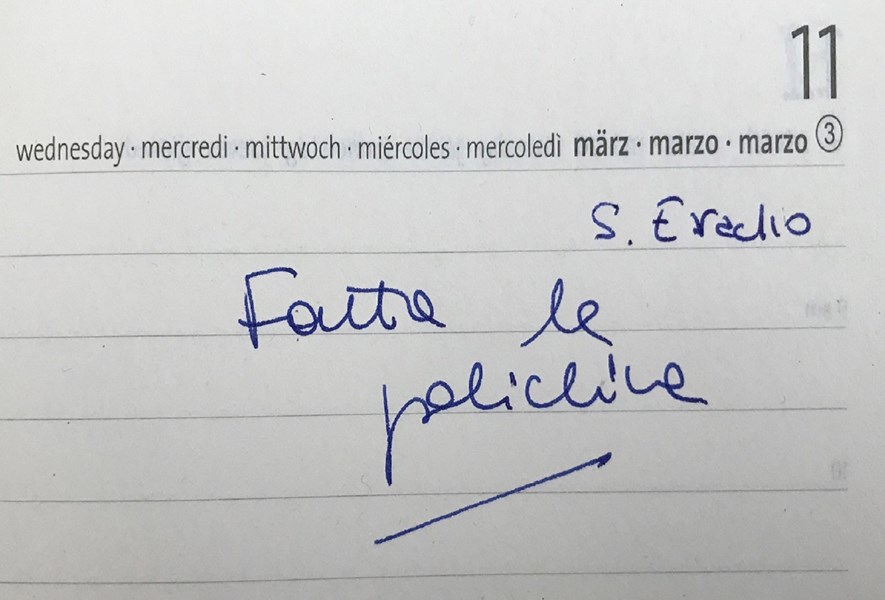

It was then that the idea of Polichina was born. In the laboratories of the “Giulio Natta” Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering, under the guidance of department head Mariapia Pedeferri, experimentation and production kicked off as of 16 March. Polichina is a liquid sanitiser prepared according to a recipe created by the World Health Organisation, as Prof. Carlo Punta explained to us during an event dedicated to the students. The ingredients are simple yet effective: ethanol, glycerol, hydrogen peroxide and purified water.

Polichina immediately garnered a great deal of media coverage, given that it was such a critical period. Since those early days, thanks to the expertise of our university, productivity and efficiency have improved to such an extent that we are now able to deliver up to 6,000 litres of hand sanitiser a day to all the various organisations in the local area. Also thanks to the support of our donors, we were able to donate more than 107,000 litres of Polichina free of charge to the local healthcare authorities, the Lombardy Civil Defence, and Milan’s three prisons (San Vittore, Opera and Bollate).

Another feature of the online lecture by Prof. Punta, was the launch of the “Polichina for Kids” initiative, aimed at young people aged between 7 and 13. They were invited to send in drawings and phrases to be turned into labels to stick on bottles of Polichina. It was a way of cheering up the otherwise serious, austere containers, allowing them to be the vehicle for a symbol of closeness and warm thoughts sent out to the people on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19.

Following the end of the most serious peaks of the health crisis, production of the hand sanitiser now serves the internal needs of the Politecnico. Total production is now over 110,000 litres.

The experience of creating Polichina is not limited to production within the university: it is intended to be a shared heritage. Indeed, to this end, Prof. Davide Moscatelli has created a video available in over ten languages that illustrates how to install a facility to produce the solution, thus encouraging its local production even in rural and periurban contexts in developing countries.