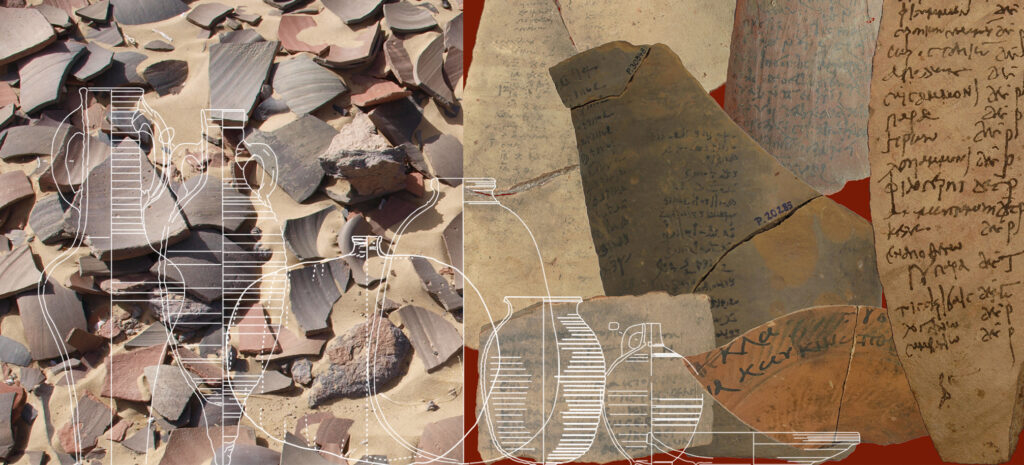

What can fragments of ceramics with writing, or ostraca, tell us? For Clementina Caputo, a researcher in the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering at the Politecnico di Milano, the answer goes far beyond the simple object. The moment a text is etched in a ceramic fragment, the shard becomes a document, or rather, an ostracon. Each ostracon is the result of an act that was done on purpose by an individual in a specific place and at a specific time. They should therefore be regarded as tools for storing memories.

From the Egyptian desert to the Louvre, via Berlin and New York, her path has revolutionised the study of ostraka, turning them from simple writing aids into actual evidence of daily life in antiquity. Now, with new technology and the lab group she is part of, ABCLab-Eidolon, directed by Corinna Rossi, Clementina is forging new paths in archaeology, showing how digital support enhances the human experience rather than replacing it. In this interview, she tells us about her interdisciplinary approach and the most surprising discoveries in her work.

You were the first to study ostraka with respect to their physical aspects. How did it all start?

My education began with a degree in Archaeology at the University of Salento, Lecce, with a thesis on Egyptology. My first research topic was Greco-Roman statuary, particularly statues from a Greco-Roman archaeological site about 90 km south of Cairo called Dimé/Soknopaiou Nesos (Fayum Oasis), which was excavated by the University of Salento. I started out as an archaeological draughtsman. I drew objects and was passionate about studying stone statues, but my curiosity has always pushed me to delve into different aspects of material culture.

After graduation, I decided to take specialised courses on archaeological objects because I was fascinated by the idea of studying materials beyond their artistic or symbolic value. Thanks to Paola Davoli, I was able to take courses at the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale in Cairo. It was a pivotal experience: I discovered the world of ceramics thanks to Sylvie Marchand, a leading ceramics scholar in Egypt and head of the Institute’s ceramics lab. I started working with her in the field, gaining experience in ceramic artefacts, and realised that this area could become my main field of research.

After a few years, I felt the need to broaden my horizons and delve not only into ceramics, but also into related objects. I won a PhD position at the University of Salento in collaboration with the Université de Poitiers in France under the supervision of Professor Davoli and Pascal Ballet, a leading expert on Egyptian ceramics. This is where I began to study ostraka, fragments of pottery used as writing surfaces in antiquity.

What prompted you to undertake this research?

My interest partly stemmed from my experience in the field, analysing ceramics, but also from an intuition that Davoli and Ballet, my two text editors, had in the course of their research, which I expanded and refined. In studying ceramic materials, I have often dealt with ostraka, but I have always seen that papyrologists’ attention was mainly directed at the text, with little or no thought for the ceramic fragment, which has always been considered poor material of little importance. Ostraka normally do not come from easily recognisable, or diagnostic, parts of a vase such as the rim, handle or base. The texts almost always tend to be on wall fragments, which makes it difficult to determine the original shape of the container. However, this stimulated my curiosity and prompted me to answer the first of many questions: What sort of vases did these fragments come from? I analysed the material and characteristics of the fragments and began to notice a number of interesting details.

I started to collect data systematically from the Demotic ostraka at Soknopaiou Nesos, taking measurements, analysing thicknesses and trying to work out which part of the vase the fragments belonged to. This research was extended to the Greek ostraka at another site in the Western Desert in Egypt, Amheida/Trimithis (Dakhla Oasis), dating from the late Roman period and excavated by New York University-ISAW. There, I realised a fundamental aspect: whereas the writing fragments at Soknopaiou Nesos came from amphorae, the ostraka at Amheida were not from amphorae, but from jars. This was a turning point. It was evident that the scribes used locally available material. This contradicted earlier theories that people only ever wrote on amphorae.

Going further, I noticed another surprising detail: in many cases, the fragments were not broken randomly. Some ostraka had regular edges that were too square to be natural. This suggested a certain intentionality in the selection and preparation of the writing medium. This was particularly evident in ostraka related to administrative practices, that is, documents used for bureaucratic and administrative purposes. At Amheida, in the house of a prominent person named Serenos, we found pairs of ostraka with the same text and shape, confirming this practice.

This research led me to reconsider the commonly accepted idea that ancient scribes used shards simply because they were abundant and cheap. Instead, I believe the use of ostraka was more organised. Some elements, such as the possible archiving of numbered fragments, suggest a document management system, although proving the steps before writing remains complex.

What fascinates me most is the potential of these fragments to tell us about everyday life in different historical periods. Each ostrakon is concrete evidence of administrative actions, exchanges, accounting entries, and, of course, also everyday things such as shopping lists, school exercises, or simple notes. Studying these materials means not only deciphering the texts, but reconstructing social and economic practices that would otherwise be lost.

What was the most surprising discovery?

One of the most curious and interesting studies was on a small group of Coptic ostraka in the collection at the Louvre. These plates were produced in the Aswan region of Egypt, made of a fine, shiny, bright red ceramic similar to Roman sigillata. Their smooth surface made the black ink stand out perfectly, making them visually very elegant.

What struck me was that all these plates were broken and bore a recurring type of text: statements of debt. They were notes in which one person claimed to have received a sum of money from another. But why were the texts always incomplete? The answer came when I contacted an expert in Roman law, José Luis Alonso (University of the Basque Country). In the Roman period, a loan included the obligation to repay it within a certain period of time, under financial penalty. But once the debt was settled, the document certifying it had to be destroyed to prevent the creditor from reusing it and demanding payment again.

This would explain why the plates with these annotations were always broken: they were not just random fragments, but documents that were deliberately destroyed to certify that the debt had been settled. It was a fascinating discovery, revealing a link between the material culture and legal practices of the time.

You have worked in France, Germany, the United States and at several prestigious museums…

Yes, my international experience started due to the interest aroused by my PhD in Germany. A scholar from Heidelberg University, Julia Lougovaya, had developed a project entitled ‘Schreiben auf Ostraka im inneren und äußeren Mittelmeerraum’, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under the SFB (Special Research Programmes), dedicated to material culture. She asked me to work with her, believing that I was the only one who could tackle the subject with an innovative approach. So I spent four years in Germany, which gave me valuable experience both in terms of academic contacts and access to important museum collections.

In fact, I had the opportunity to analyse ostraka housed in prestigious institutions such as the Louvre, New York University and several museums in Berlin. This allowed me to collect data that was fundamental for my research, comparing excavated materials with those found in museums.

A particularly significant moment came in Berlin, where I was studying a group of ostraka found in 1909 and 1910 at Soknopaiou Nesos, a campaign I have been participating in for 25 years. I was able to recompose some texts, linking individual fragments with those from the excavations. This helped not only me, but also the papyrologists I was working closely with. Traditionally, ostraka were studied only as texts, without considering the ceramic medium. My approach led to a new perspective, which was welcomed enthusiastically in the scientific community.

How have these experiences influenced your approach to research?

My international experiences have taught me a lot, both academically and personally. I was fortunate to work with curators who were always available, but I also experienced the varied logistics of accessing the collections. For example, it was complicated to organise appointments at the Louvre, especially because they were busy preparing the Louvre in Abu Dhabi at the time. In Berlin, I was initially assigned a shared room with other scholars, but since my study required that I analyse a large number of ostraka, they adapted their method by taking me to the warehouses, which was a fascinating experience.

In the United States, on the other hand, I found a more direct and collaborative approach. Both New York University and the Kelsey Museum opened their warehouses to me willingly, allowing me to freely explore the collections.

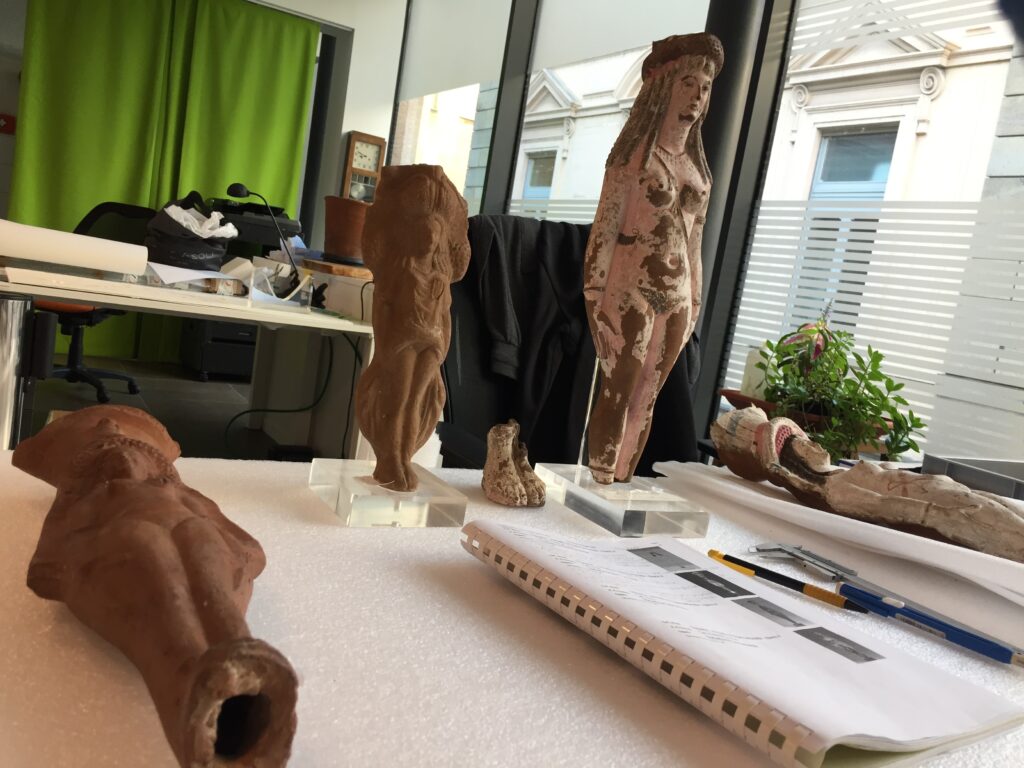

I had an exceptional experience at the Egyptian Museum in Turin, where I studied terracotta figurines during the pandemic (2020–2022). Despite the restrictions, their welcome was incredible. At the end of the restrictions, I remember having coffee with some registrars and curators and they said: ‘We have never seen you without a mask!’ Another aspect that struck me about Turin is their openness to sharing knowledge: everyone should be able to see and enjoy the objects.

These experiences taught me to respect the times and working methods of each institution, to be flexible and build lasting professional relationships with colleagues. I realised how important it is to create a network of contacts and maintain it over time through conferences and collaborations. Finally, I apply the same approach with students in the field. I do not set the pace, but teach them to manage their time and deadlines independently, because this is what it means to be a professional.

Your current SUR.VI.VE project on Egyptian terracotta figurines has received the Seal of Excellence from the European Commission. What are the main goals?

After four years in Germany, I had the opportunity to return to Italy. I submitted a project for a Marie Curie Fellowship at the Politecnico di Milano under the scientific direction of Corinna Rossi, and although I did not win the call for applications, I received a ‘Seal of Excellence’ grant from the European Commission as a fellow at the Politecnico.

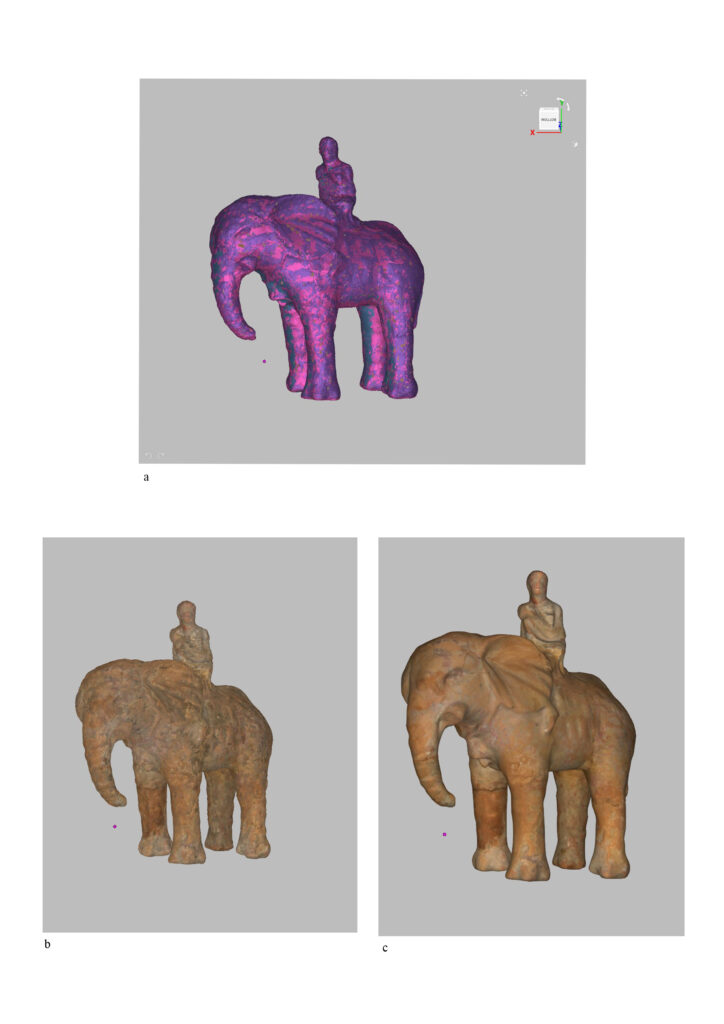

SUR.VI.V.E –Surveying Virtual Voids in Egyptian collections. A Digital and Cultural Study on Terracotta Figurines and their Lost Molds – focuses on Egyptian terracotta figurines, which are less explored in archaeology than large statues or sarcophagi. These neglected statuettes, on the other hand, tell a great deal about everyday life, popular beliefs and rituals at the time. My goal is to analyse them not only with respect to the material and iconography, but also technologically and digitally, drawing on technology available the Politecnico di Milano and in the ABCLab-Eidolon group. The success of this approach is indicated by the extension of the SUR.VI.V.E. project to a second phase, with funding from the European Union (Next Generation EU) under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), for which I was reappointed as a fixed-term researcher.

How is technology revolutionising archaeological studies?

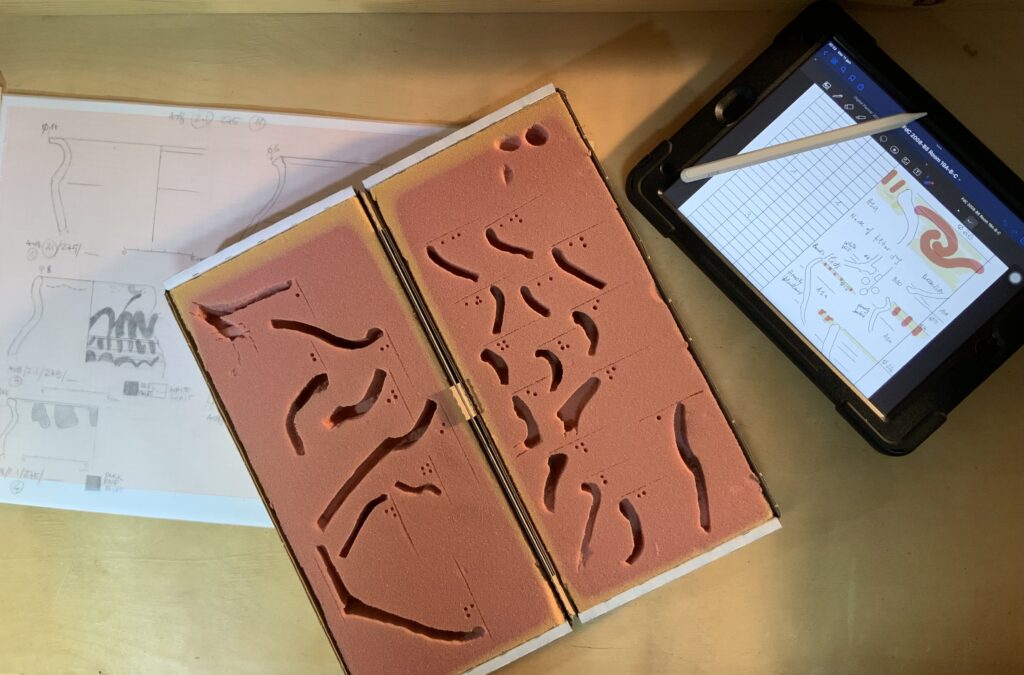

One of the most innovative aspects of the project is the application of 3D modelling to the figurines. Working with Alessandro Mandelli and the ABCLab-Eidolon team, we digitised over 600 previously unpublished terracotta figurines from the collection at the Egyptian Museum in Turin in 3D. This allowed us to:

- virtually reconstruct the figurines and study details that are difficult to analyse with the naked eye;

- identify the original moulds. Many figurines were produced with matrix moulds, which means there are replicas of the same model. Using 3D models, we can compare the surfaces of the figurines to see if they came from the same mould, helping us reconstruct their production and distribution;

- analyse the quality and variety of artefacts. Some statuettes show refined details and careful workmanship, while others are simpler and more stylised. This suggests the existence of a market with different price ranges, as is the case today with devotional objects;

- study the context of use. For example, I analysed Coptic female statuettes in a position of adoration, with their arms raised, and found that they show intentional, systematic fractures. They were probably sold to women as fertility objects near shrines. If the pregnancy was successful, the figurine was broken, otherwise it remained whole and buried with the owner.

The project is not limited to academic research. One future goal is to also make these figurines accessible to blind people by printing 3D replicas so that they can be touched and understood on a tactile level.

I have worked for several years with Italian and international archaeological institutions and excavations, such as the excavation at Umm al-Dabadib directed by Corinna Rossi from the Politecnico, the one at Dimé/Soknopaiou Nesos by the University of Salento, the one at Tuna el-Gebel by the Landesmuseum Hannover, the excavation at Amheida/Trimithis by New York University (for which I am deputy director), the one at El-Deir by the Sorbonne and the one at Coptos by the Egyptian Museum in Turin. Thanks to the NRRP, the SUR.VI.V.E. project continues, and 3D modelling is gaining ground in these areas, radically changing the way we study archaeological objects, allowing us to reconstruct the history of objects and the people who used them in previously unthinkable ways.

You often talk about the importance of studying recycling and reuse in antiquity. What lessons can we learn from the past to address today’s environmental challenges?

The way in which materials were recycled and reused in antiquity are key topics, and ceramics is one of the most fascinating examples. The ostraka themselves represent a form of reuse, because they are broken ceramic fragments on which all kinds of information was written, from literary texts to administrative notes.

In ancient Rome, for example, there was an actual system to collect and sort ceramics, very similar to today’s recycling methods. Fragments of broken vessels were collected and reused in different ways. For example, in construction, ceramics were used to strengthen masonry. The necks of amphorae were turned into pipes for aqueducts or drainage systems. In Egypt, some ceramic fragments were used as grave markers, while they served as pots or substrate for nurseries in agriculture.

This mentality of reuse in antiquity offers interesting insights for contemporary environmental challenges. Today we are faced with a global crisis that makes the circular economy a necessity. The way the ancients used every available material teaches us that nothing should be wasted and that every object can have a second life with the right approach. Sustainable solutions are not a modern discovery, but were often successfully tested in the past. Perhaps we should rethink our relationship with objects, abandoning the throwaway logic and returning to a model where resources are used to their full potential. The study of recycling in antiquity is not just an academic exercise, but can offer concrete inspiration for developing new sustainable strategies.

You are one of few archaeologists at the Politecnico. How do you integrate your discipline into a traditionally engineering context?

Archaeology in an engineering context may seem unusual, but it actually fits in perfectly when looks with curiosity at interdisciplinarity. Look for points of contact and you will find that there are many more connections than you might imagine. For example, the concept of stratigraphy, which is used in archaeology to analyse the deposition of layers over time, has a counterpart in architecture, where vertical stratigraphy allows one to reconstruct the history of changes a building has undergone over the centuries.

Another area where archaeology and engineering meet is the use of 3D technology to reconstruct artefacts. When we find fragments of pottery, we can often trace the original shape of the vessel through a 2D drawing, but in 3D, we can also calculate its capacity. These studies are essential for understanding water management in ancient settlements, for example. At Umm al-Dabadib, we found specially shaped ceramic containers that were used to transport water and were directly connected to aqueducts. By digitally reconstructing these vessels, we can estimate the amount of water that was transported, providing valuable information for those studying water management in the past.

The interaction between man-made structures and the environment is another point of contact between archaeology and engineering. In the Western Desert, for example, the high temperatures and wind require precise construction choices. Buildings were positioned and designed to create shaded areas and ensure survival, just like in Spanish or Italian cities with their narrow streets. Another interesting example concerns the reuse of materials. During the excavation of a house belonging to a city councillor, we found layers of overlapping beaten floors that were periodically reworked with water and mud. This shows continuous maintenance and adaptation of the living space. Likewise, the transformation of a banquet hall into a private street shows how the urban environment was constantly changing, just as it is today in our cities.

These connections show that archaeology is not at all out of place in an engineering context. On the contrary, it can offer a unique perspective on design, resource use and the human capacity to adapt to the environment. There is also a fascinating aspect that I always like to remember: if someone were to analyse our era in a thousand years using the objects we leave behind, what would they discover? It is a question that helps us reflect on the way in which we build and consume today.

When you study materials, can you also follow their evolution over time?

Yes. The evolution of materials and technology is evident over the centuries. For example, we note significant transformations in production techniques when analysing ceramics. Initially modelled by hand, ceramics developed through the coil technique and then with the use of the throwing wheel, which was first operated by hand and then with the foot, making work faster and more precise. In the Roman and Byzantine periods, the quality of the clay improved considerably, with treatments to reduce voids and increase compactness, as well as better management of firing in kilns.

Cultural influences played a crucial role in the evolution of materials. The Mediterranean was a lively market for trade, and ceramic products spread between the different regions. Italy, for example, exported terra sigillata to North Africa and Egypt. There, terracotta mortars produced near the Tyrrhenian in the Roman period can be found, as they were often used to balance ship cargoes and were then resold at the markets. This shows how modern practices, from logistics to global trade, are rooted in processes that already existed in the past. The connections between different cultures and continuous technological innovation show how progress results from a long historical evolution.

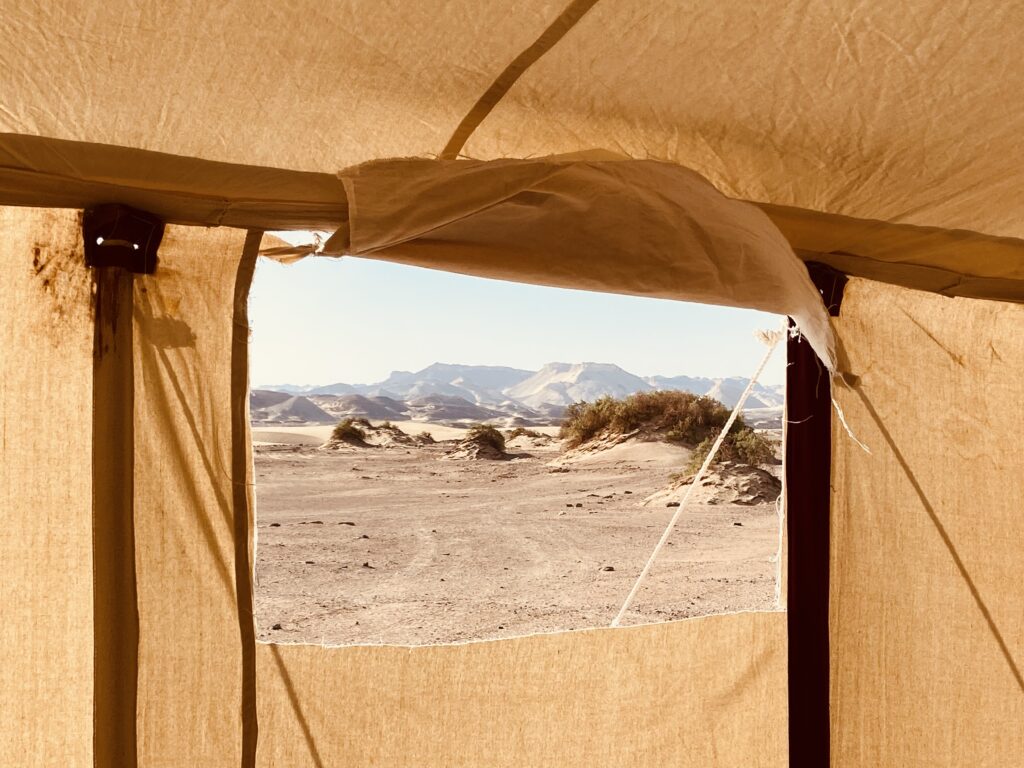

You participated in numerous missions in the Western Desert in Egypt. What were the biggest challenges?

Each mission in the Western Desert brings unique challenges, despite my experience in more than 25 years. The main difficulty I find each time is to adapt my working method to each new situation and excavation. Although I follow a precise, orderly method with a strong emphasis on stratigraphy (which allows me to gather information from each excavated layer), each excavation has its own particular aspects. Some excavations are more structured, such as stratigraphic excavations, which require careful cataloguing of each layer and its connection to other layers. Other excavations, on the other hand, follow different methods, such as assays or the excavation of rooms without stratigraphy, where the interpretation of the materials must be adapted to the specific excavation method.

Another big challenge is teamwork. An archaeological site can involve many people, from 10 to 40, including specialists, ceramologists, numismatists, ancient text experts and many others. Each person plays a fundamental role, but sometimes, especially with some excavations, I held more than one position, such as ceramologist and object distribution manager. This increases the complexity of the work, but it is also very stimulating.

In addition, the desert environment can be as fascinating as it is extreme. The daily routine is intense. We wake up early, dig in the desert heat until afternoon, and then continue the work on the finds and data. It is a full-time commitment that absorbs you completely. But there are also moments to relax, such as Fridays off, which allow for excursions and visits to other archaeological sites to compare discoveries and expand our understanding. The working environment may seem monotonous and isolated, but it also offers opportunities for interaction and continuous growth, where every small detail contributes to reconstructing the history of ancient civilisations.

With the increasing use of digital tools and interdisciplinary technology, how do you see archaeology evolving in the coming years?

The introduction of digital technologies in fieldwork has been a real revolution. The use of tablets, for example, has made it possible to collect and document data in real time, helping to digitise the process. In excavation, digital tools are now essential for visual documentation, from photography and photogrammetry to the creation of excavation plans. Archaeologists are also trying to integrate these technologies in the management of excavation records, marking an important step forward for the discipline.

However, digital technologies should not be seen as a substitute for traditional methods, but rather as support. Even artificial intelligence, which is often met with scepticism, can prove to be a valuable tool if used correctly. What is important is to maintain a balance with analogue practices, which are still fundamental when it comes to correctly interpreting the data. No matter how advanced the technology is, humans remain irreplaceable.

One example concerns a recently patented laser scanner system for scanning shards and automatically generating the profile of the object. Although this technology reduces manual work in the laboratory, it cannot replace the draughtsman in the field, where operating conditions are more complex. In Egypt, for example, technological resources are limited, and even carrying callipers can be problematic. Moreover, machines cannot interpret details like an expert would. In the end, technology is a valuable ally, but human experience remains essential for an accurate reading of the findings.

What ambitions do you have for the future?

My ambitions mainly relate to passing on what I have learnt over the years. I would really like to convey a passion for archaeology and research, inspiring as many people as possible. One aspect that I hold dear is teaching my approach, my way of working and the methods I have developed in the field. My hope is that someone will pick them up and continue with them, because at a certain point you feel tired, but the work must go on with new energy and fresh ideas, maybe introduced by young people.

From an academic point of view, I also dream of being able to write a book collecting all the evidence on ostraka in the Mediterranean and defining a universal method of study. I am not very interested in leaving my name in history; that is not my goal. Rather, I would like to contribute something that can also be of use to those who come after me. Maybe fifty years from now a student will be studying a similar topic and will find a work of mine that sparks an interest to go further, to evolve the topic or delve into it more deeply. Basically, I would like to leave a piece of the puzzle, a contribution that will be useful for future research.

What most excites you about your work?

What excites me most about my work is the possibility of discovering objects that tell stories of everyday life. Every find is a surprise, like when we found children’s leather sandals in a Roman building inside a temple area that might have been a school, and wax tablets that scribes wrote on as if they were magic slates. These objects, which are seemingly simple, have the power to make us travel through time and imagine the people who used them centuries ago.

Another striking aspect is the audience’s — and especially children’s — reaction. When they visit a museum and see such ancient artefacts up close, their eyes light up with wonder. Teenagers, on the other hand, often appear less involved, perhaps because they see history as something remote. Yet if they could understand that everything they learn can hold surprising, solid value, their curiosity could be rekindled.

Finally, I find the connection between these finds and the human side of the story fascinating. I remember my visit to the Material Culture Galleries of the Egyptian Museum, where vases, natural pigments and botanical elements used to create objects were on display. Such rooms take us back to a past that is still alive, almost as if the people who used the objects can still speak to us. Every time I find such remains, I feel an emotion that is difficult to explain, but which gives me an even greater desire to continue my work.