Life

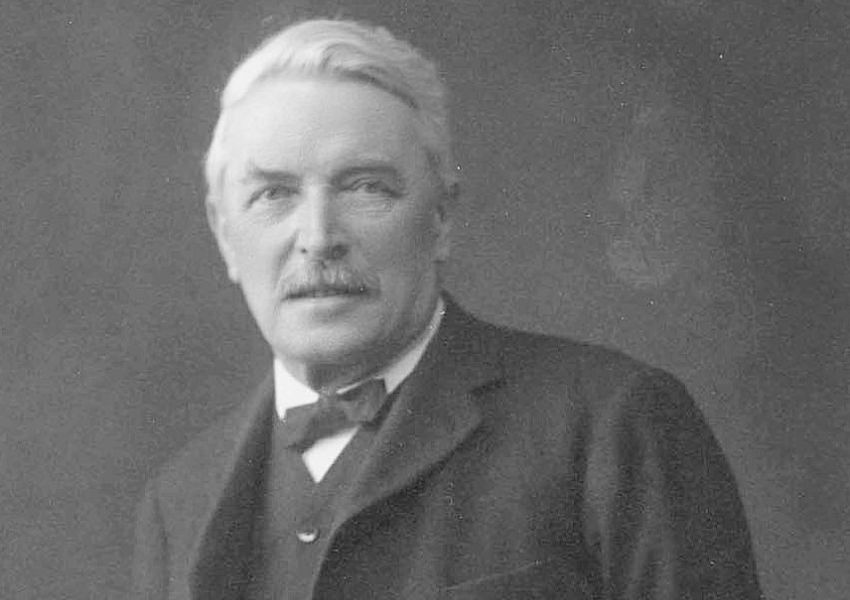

Luca Beltrami was born in 1854, in a Milan still under Austrian rule. Luca Beltrami was born in 1854, in a Milan still under Austrian rule. Only six years had passed since the Five Days of Milan, and we were in the midst of the Risorgimento (the unification of Italy).

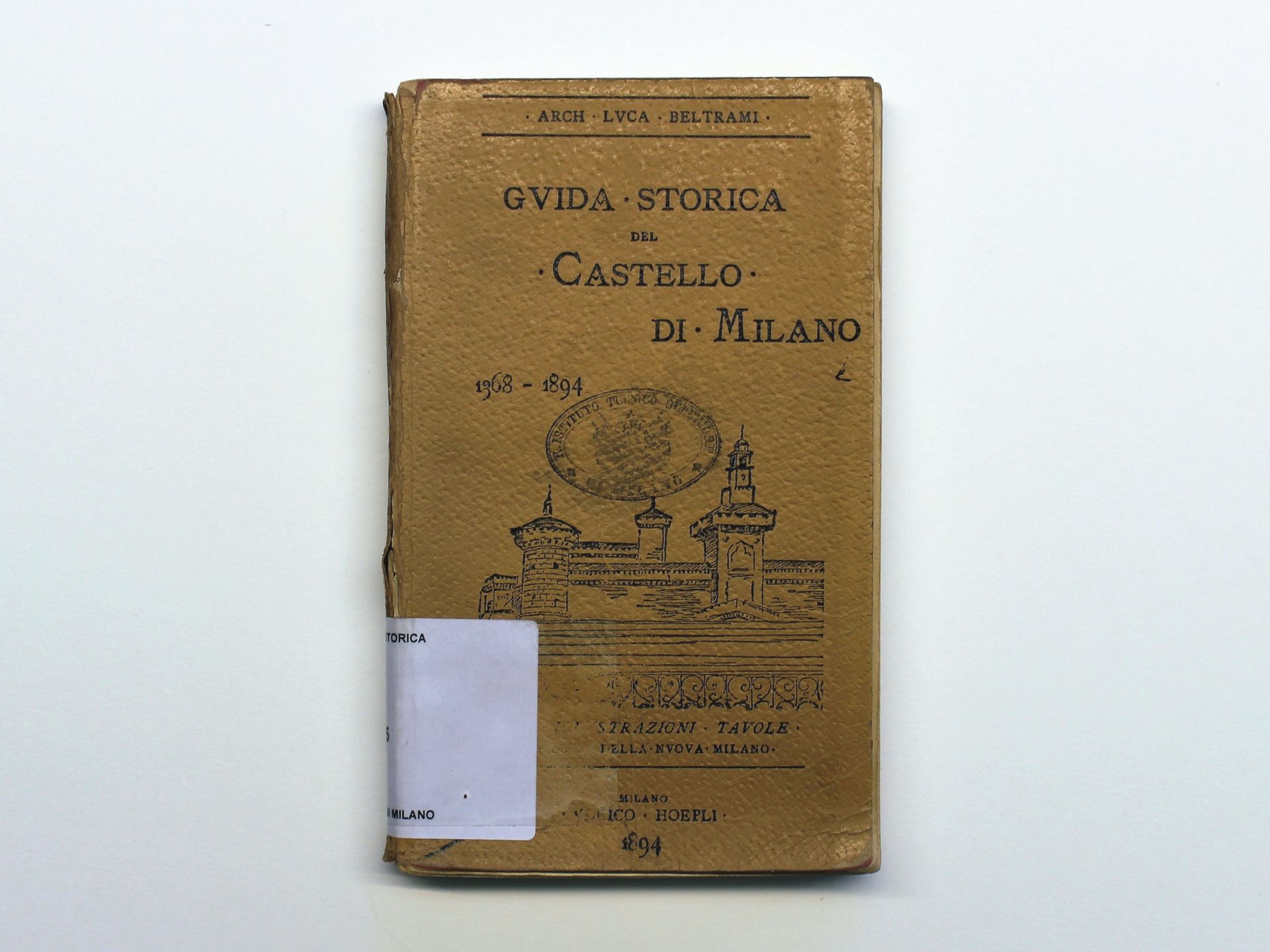

After obtaining his technical high school diploma in 1872, he enrolled at the Politecnico di Milano, then called Istituto Tecnico Superiore. The new university, founded by mathematician Francesco Brioschi in 1863, was part of a complex project to organise higher education that sought to link all the city’s scientific bodies, seeking synergy with entrepreneurial activities, to promote an economic progress that the ruling class of the time did not see as separate from that of civil and political institutions.

Having successfully passed his entrance exams in the field of descriptive geometry, he was encouraged to choose architecture by his friend Luigi Conconi, a painter and architect, who introduced him to the Scapigliatura, a leading movement in the Milanese cultural milieu of the time.

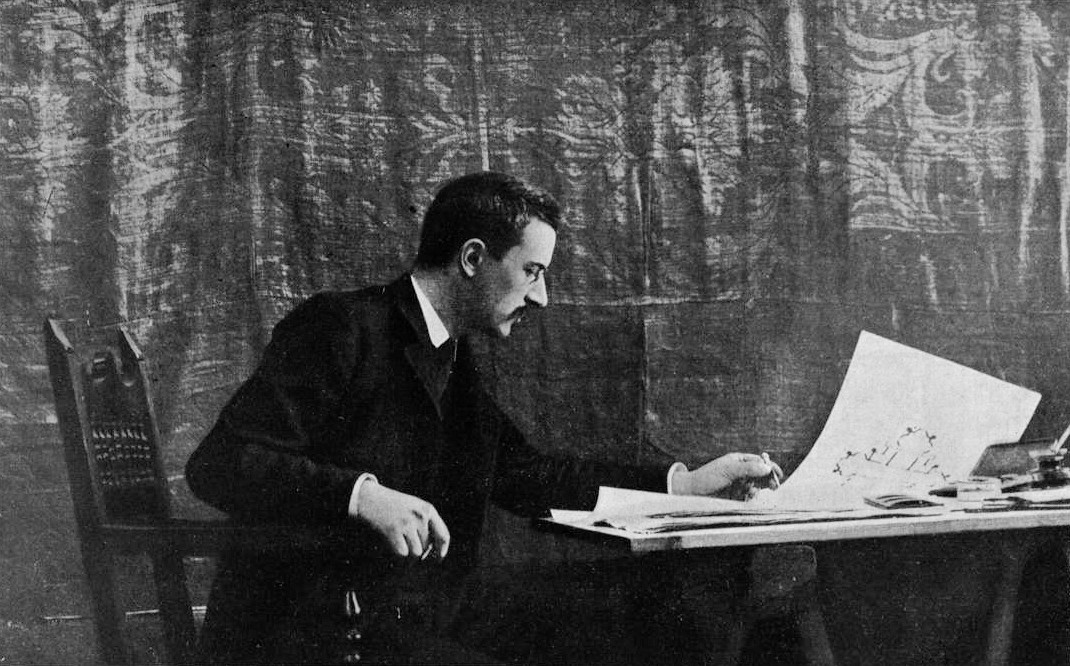

Luca Beltrami was an excellent pupil: his mentality was rational and positive, but at the same time pervaded by an artistic vocation that manifested itself in etching. It is said that it was precisely Francesco Brioschi, during a mathematics lesson, who caught young Luca etching on a copper plate. During several school trips organised by the Politecnico in the spring of 1875 to Padua, Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples, Beltrami devoted himself to sketches of their fascinating landscapes.

His studies at the Politecnico earned him the esteem of Camillo Boito, a national point of reference in the debate on architecture, highly influential in the politics of art education, director of the Schools of Architecture at the Politecnico and at the Accademia, where he is the only professor.

Conquered by Camillo Boito’s sharpness and stubbornness, the civil architects section of the Istituto Tecnico Superiore, established in 1865, was part of the modernist project of a city that identified its geographic location as the economic heart of northern Italy and the nation’s link with European territory. The ‘polytechnic’ education, influenced by the professional world that came to terms with the advancement of industrial civilisation, proposed a rationalist approach to architecture, thanks to the inclusion of scientific disciplines, also taught by engineers, alongside the architectural and drawing ateliers.

The section, which provided technical courses alongside artistic ones taught by the same teachers as the Brera School of Architecture, allowed, after attending the school for three years and passing the exams, access to the free practice of the profession of civil architect and differentiated between its graduates and those from the Accademia. The latter were eligible to become professionals in architectural drawing, but not in design.

In August 1876, Beltrami graduated in civil architecture with 38/40 and moved to Paris, where he supervised the reconstruction of the Hotel de Ville in Garnier, after attending the École National des Beaux-Arts as the first Italian student.

In 1879, he took part in the competition announced for the monument to the Five Days of Milan, which would have decorated the city gate that had been renamed Vittoria after Unification. But the proposal for a tower crowned with a ‘Vittoria’ did not meet the commission’s demands, and the competition was won by Giuseppe Grandi, with the monument that we are still able to admire today.

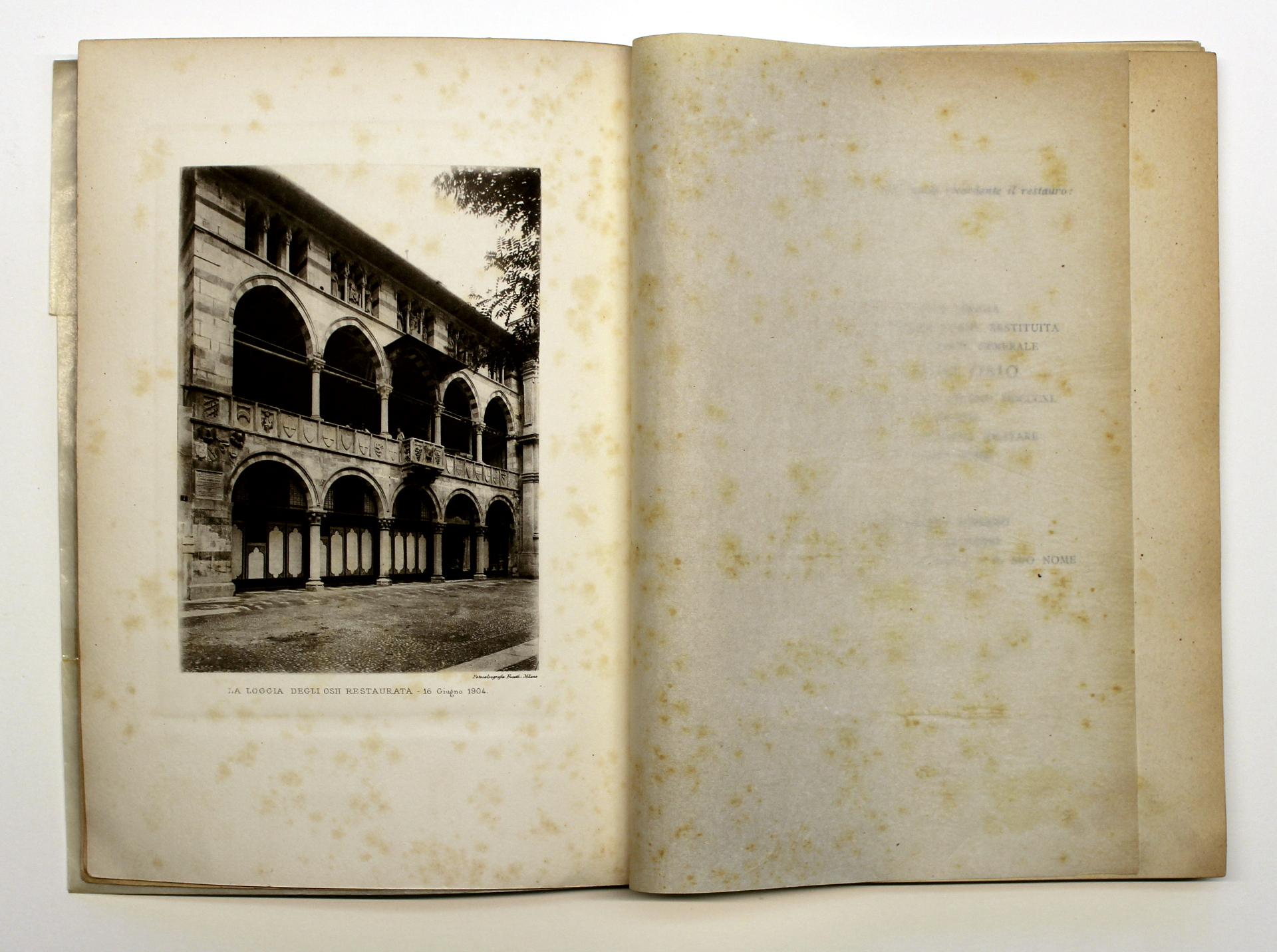

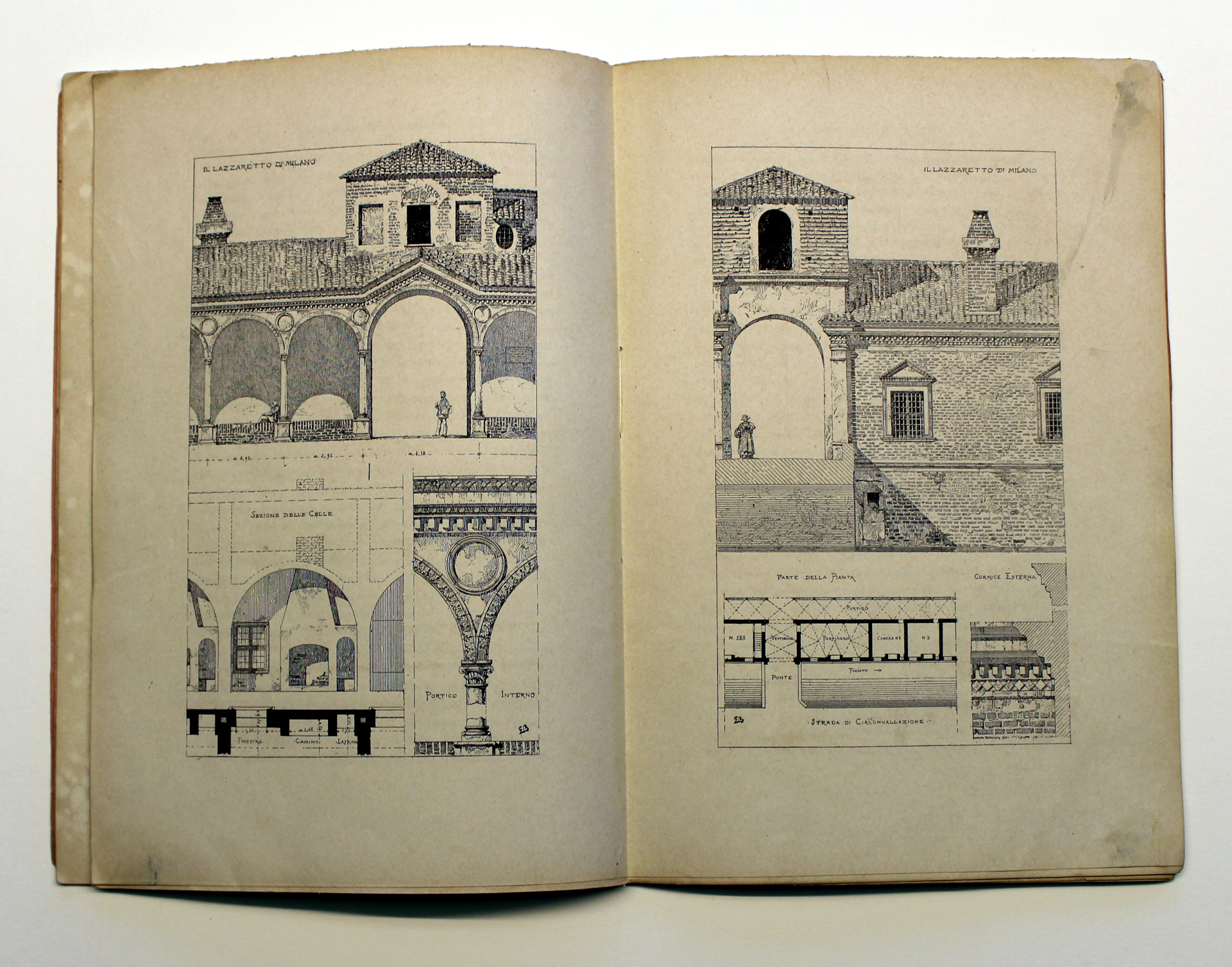

Returning to Milan in 1880, 26-year-old Luca Beltrami was a professor at the Accademia, an unattainable goal for many older artists with prestigious careers. In April 1881, he was made an honorary member. In addition to the commission for the survey of the Lazzaretto in 1881, Beltrami was also given that of the Rocca di Soncino in 1882.

In 1886 he substituted Archimede Sacchi in the ‘free architecture’ course. Boito had paved the way for him, often substituting for him and in 1885 pointing out the young man’s qualities to director Brioschi so that he could spur him on. After Sacchi’s death in 1886, Beltrami was appointed extraordinary professor of Practical Architecture, a teaching course for both student civil architects and student industrial engineers. For the Boitian group, an architect holding a course also aimed at future engineers was a great victory. In 1890, Beltrami resigned to stand in the political elections.

Luca Beltrami was not only an architect, but an intellectual with a variety of aptitudes, a figure entirely organic to the liberal-conservative culture that administered Milan at the time. His career, consciously and effectively planned, would see him as an architect, conservator, protagonist of the protection of monuments in Lombardy with national functions and authority, historian of architecture and art, Leonardo scholar and transcriber, protagonist of many cultural enterprises, founder of magazines, journalist (for a brief period director of the Corriere della Sera), satirical author, talented caricaturist, narrator and author of socially critical stories, tireless polemicist on the most varied issues, successful politician. Noteworthy are the satirical tales about the imaginary village of Casate Olona, often signed with the pseudonym ‘Polifilo’ or the anagram ‘Marcel Libaut’, which appeared in various Corriere instalments.

The mayor of Milan, Gaetano Negri, wanted him as councillor for Construction in 1885, but the liberal and conservative Beltrami would not refrain from denouncing the errors of the municipal administration anyway.

Just when Beltrami was determined to leave political activity, in November 1890 he was offered candidacy for the Chamber of Deputies in the first College of Milan. He was a deputy for three successive legislatures, and in 1905 Giolitti wanted him to be a senator of the Kingdom.

Embittered by the political events in his city, Beltrami left the Lombard capital in 1920 to settle in Rome. Pope Achille Ratti called him to the Vatican as conservator of the Papal States, a position that allowed him to be awarded the design of the Vatican Picture Gallery in 1931. As director of the new urban development plan for the Holy City, he also worked on the redevelopment of the Tiber and the Tiber Island.

He died a year after finishing work on the Vatican Art Gallery, in 1933. His body was transported to Lake Orta, to Cireggio, where Beltrami spent the summer as a boy; later his body was laid to rest in Milan’s Monumental Cemetery.

Beltrami: historian of architecture

The history of architecture written by Beltrami, right from his early work on the Lazaretto of Milan, follows in the wake of the culture of positivism: it is based on facts; it analyses the motives behind the making of architecture; it examines how it responds to practical needs, those of the client and the community; it is almost a modern social history.

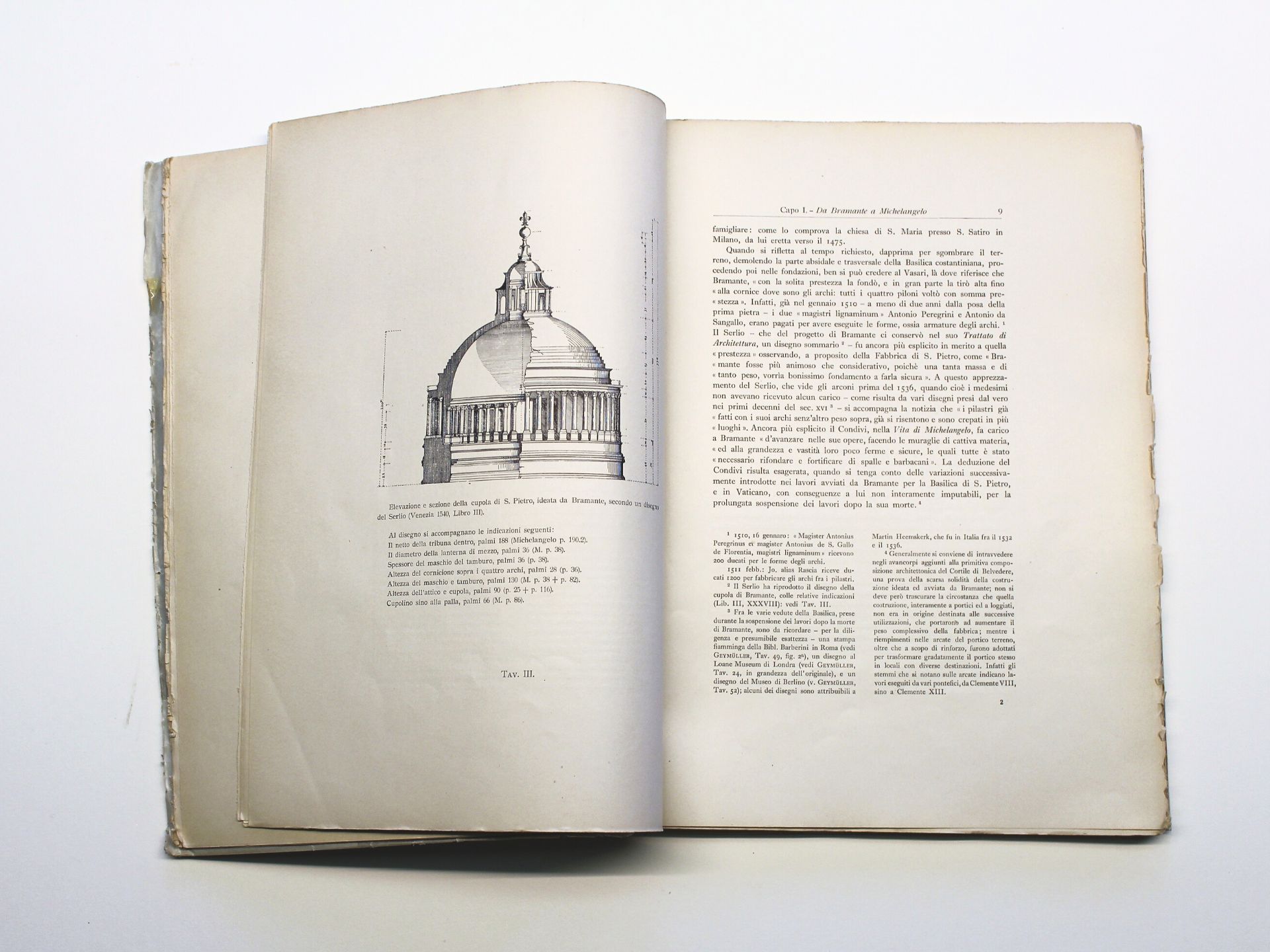

Its horizon is vast: the main topics are the great Lombard monuments such as the Duomo, Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, the Charterhouse of Pavia, the Abbey of Chiaravalle, Sforza-era architecture in general, the Lombard works of Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci; the regional dimension is favoured, but there are many dozens of articles on other Italian and foreign geographical areas.

His multifaceted activity also manifested itself in the field of museography: he collaborated on the reorganisation of the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana with the prefect Achille Ratti, he destined the Castello Sforzesco for an organic series of museums, planned the Pinacoteca Vaticana and designed its interior layout, down to the minutest details, right down to the frames of the main paintings.

Beltrami: conservator

Intense and assiduous is his vocation for the preservation of the artistic heritage of numerous Italian cities, in particular Milan and Rome, although his battle will not always have positive results as, in many cases, the destructive urge will prevail. A Milanese example is the Pusterla dei Fabbri that stood at the end of Via Cesare Correnti, the last vestige of the six major gates that delimited the city.

On the other hand, the Castello Sforzesco, Palazzo Marino, the Lazzaretto, the Torre San Gottardo, the Abbey of Chiaravalle, the church of Sant’Ambrogio, the Palazzo dei Giureconsulti with the adjoining Piazza Mercanti and the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie have been returned to the Milanese thanks to the tireless architect’s care.

He became a member of the Commission for the Conservation of Monuments, i.e., the Ministry’s advisory body for the protection of architecture considered to be of historical-artistic importance; he was a member of the Superior Council of Antiquities and Fine Arts, the institution that ultimately decides on restoration issues; he was appointed delegate of the Ministry for the conservation of monuments in Lombardy; in 1892 he was director of the Regional Office for the Conservation of Monuments.

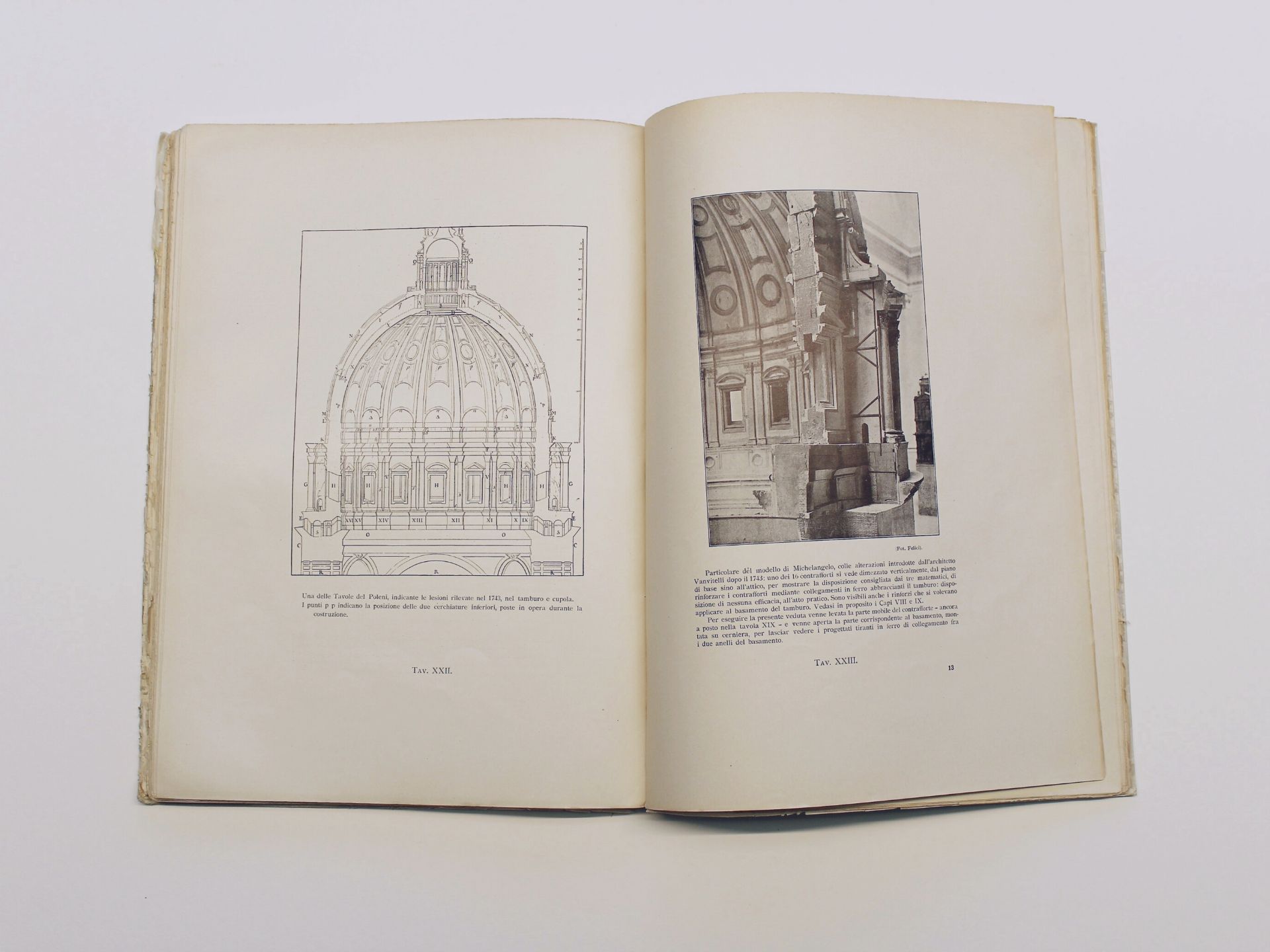

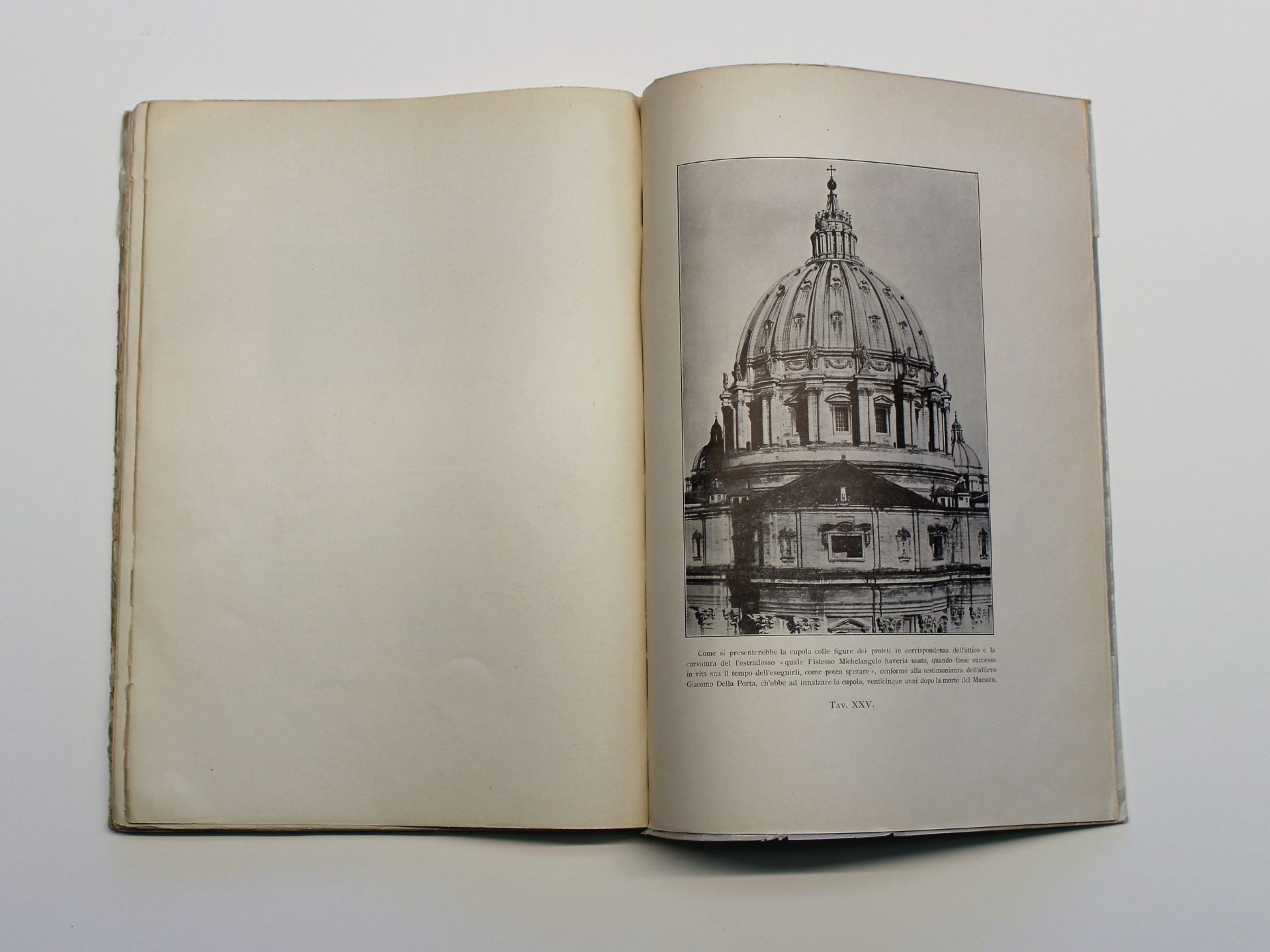

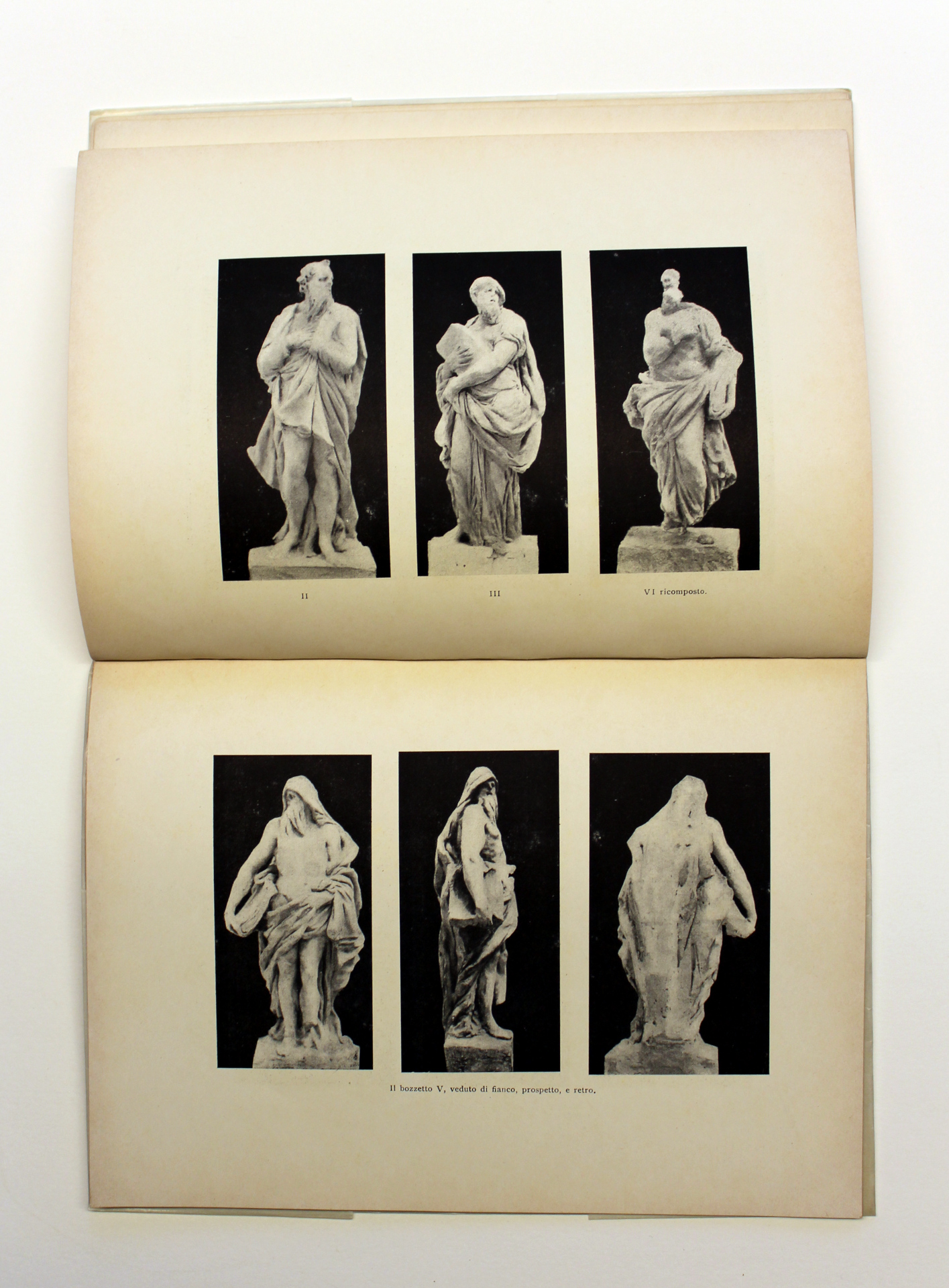

During the period in which he was in charge of the Regional Office, many buildings in Lombardy were restored, such as the grandiose reconstruction of the Castello Sforzesco, which became the seat of civic museums and cultural institutions, the work on Santa Maria delle Grazie, the Certosa di Pavia, the Duomo di Brescia, and the early Romanesque buildings in Milan and Como; He also gave expert opinions for the Basilica Palladiana and the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, the Cathedral of Piacenza, and the bell tower of St. Mark’s, all works between the last two decades of the 19th century and the first decade of the new century; the restoration of the dome of St. Peter’s in Rome dates back to the last years of his life.

The meaning of his action was, in his own words, patriotic: the knowledge of art, its presence, has the function of making everyone understand, even more so to make them feel with all the soul of which a man is capable, that they belong to a common civilisation; the formation of national consciousness was the underlying purpose.

Beltrami was the protagonist of overcoming a stylistic restoration based on emotional impressions, in which the building was brought back to a unitary form generically belonging to its period of origin; he is the founder of the method that was defined as ‘historical’, even as it was being developed.

Beltrami: builder

Beltrami’s culture of architectural eclecticism is not the adherence to a customary way of working in his time, but a deeply felt practice, a further link with history and tradition, which he will always uphold.

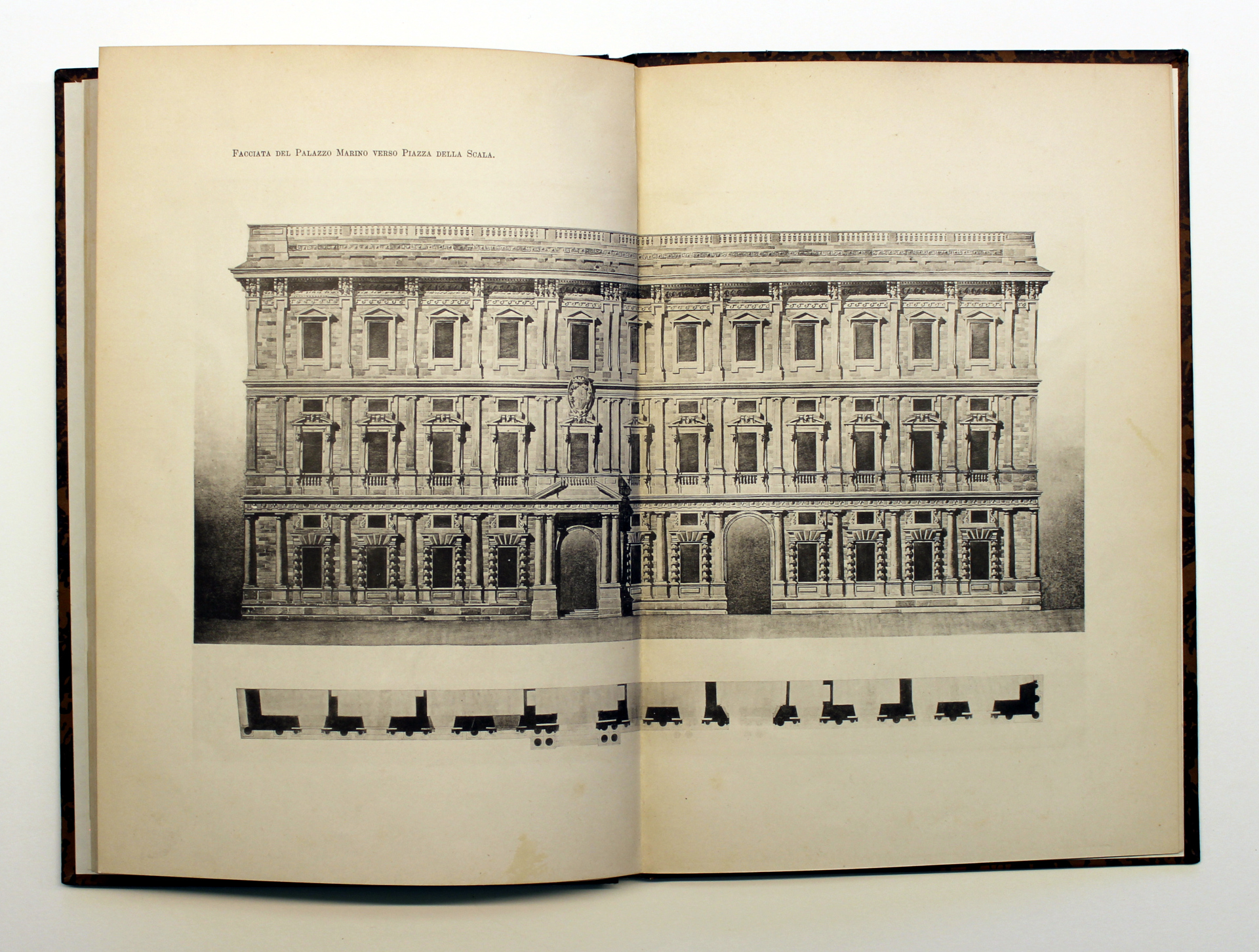

His most important buildings in Milan are: the Palazzo per l’Esposizione Permanente in Via Turati (1883-1885); the headquarters of the Corriere della Sera in Via Solferino (1903-1904); the buildings for the Assicurazioni Generali (1897-1901) and Dario Biandrà (1901-1903), which line the eastern side of Piazza Cordusio; the two buildings for the Banca Commerciale Italiana (1906-1911, towards Via Manzoni; 1919-1927, towards Via Santa Margherita) which, together with the front of Palazzo Marino (1886-1892), give shape to Piazza della Scala, one of Milan’s most important landmarks; the Bernasconi houses in Via Mascheroni (1911-1912).

They are all buildings that echo the themes of Renaissance architecture, mainly from the 16th century, with outcomes ranging from classicism in its simplest forms to a mannerism that is measured in its general forms and very marked in its architectural and decorative elements.

Although Beltrami did not build much, and did not play a particular role in Milan’s urban planning, he characterised some of the city’s liveliest spots: the Castello Sforzesco is one of the most frequently visited places, Piazza Cordusio, and above all Piazza della Scala, which is his architecture on all three sides.

Luca Beltrami’s Milan

Palazzo della Permanente

In 1883 Beltrami received the prestigious commission to build the headquarters for the Società per le Belle Arti ed Esposizione Permanente. The building is located along the city’s expansion route towards the central railway station, following Via Manzoni at the end of which are the ancient arches that had been the subject of great controversy in the mid-century between conservators and demolishers; a crucial point at the junction between the old and new city. The architecture, built between 1885 and 1886, was designed by Beltrami in Renaissance style, with forms inspired by the late 15th century.

The rearrangement of the Piazza del Duomo

The problem of layout of Piazza del Duomo and its surroundings had been debated throughout the 19th century.

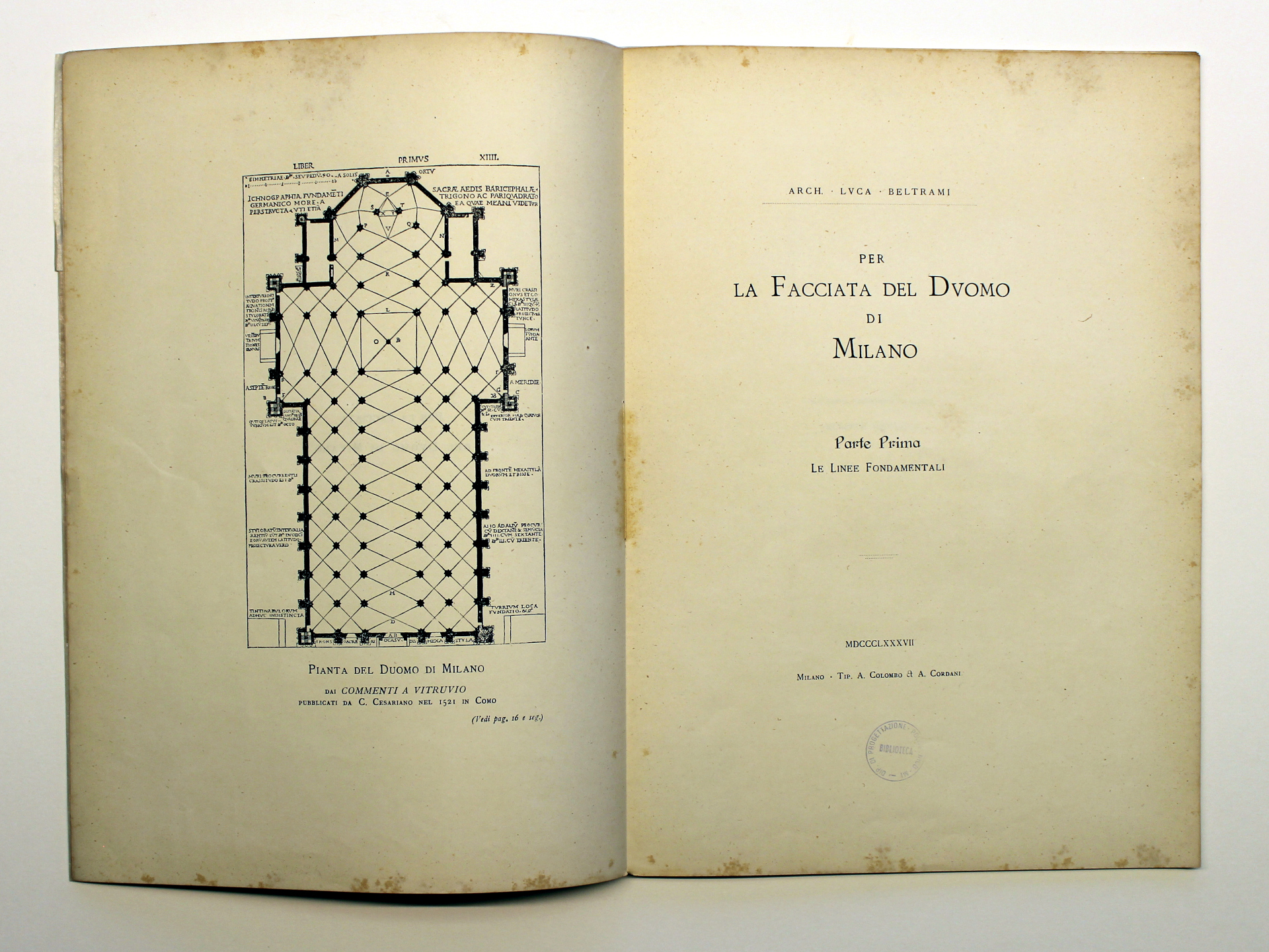

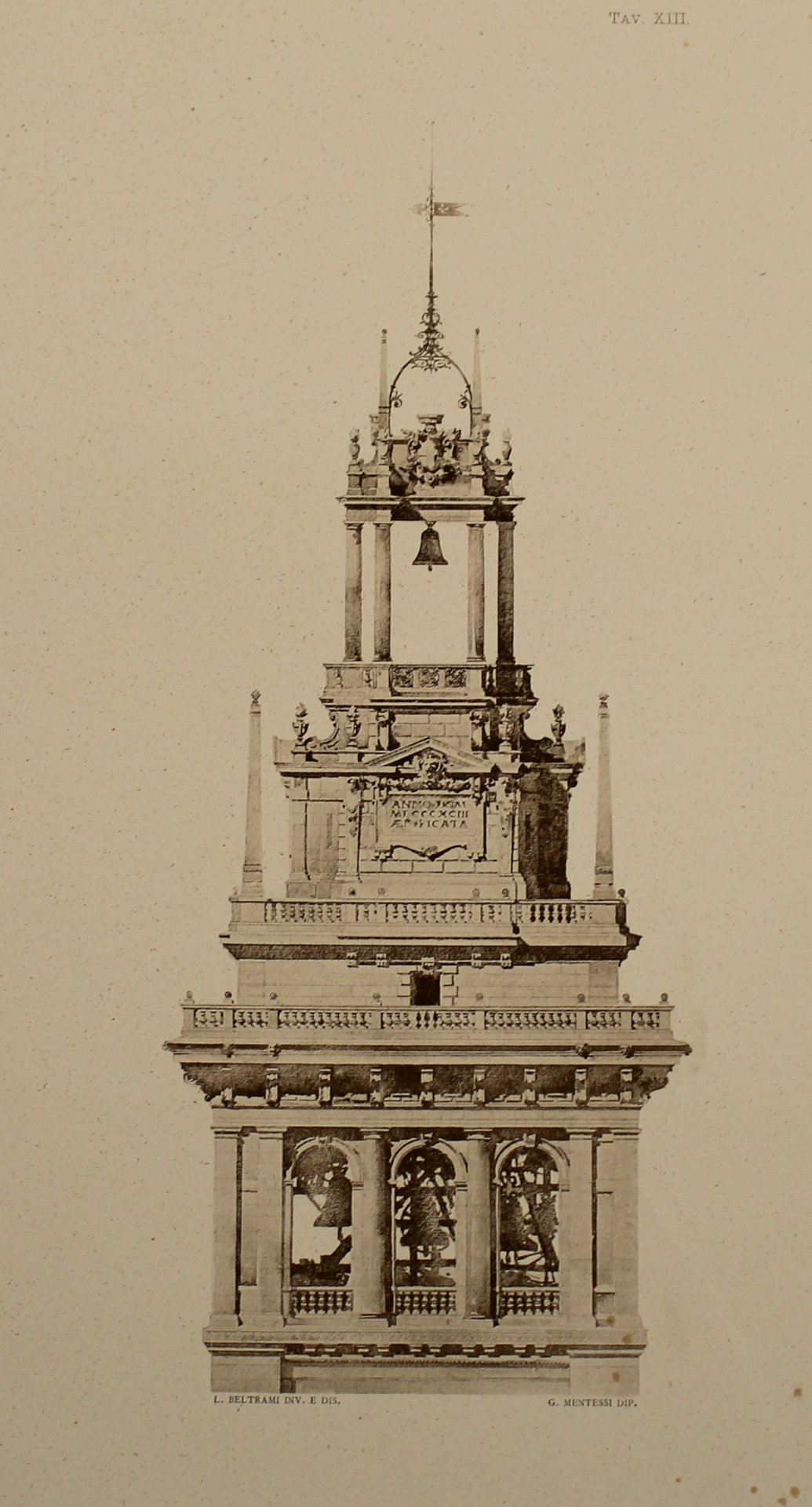

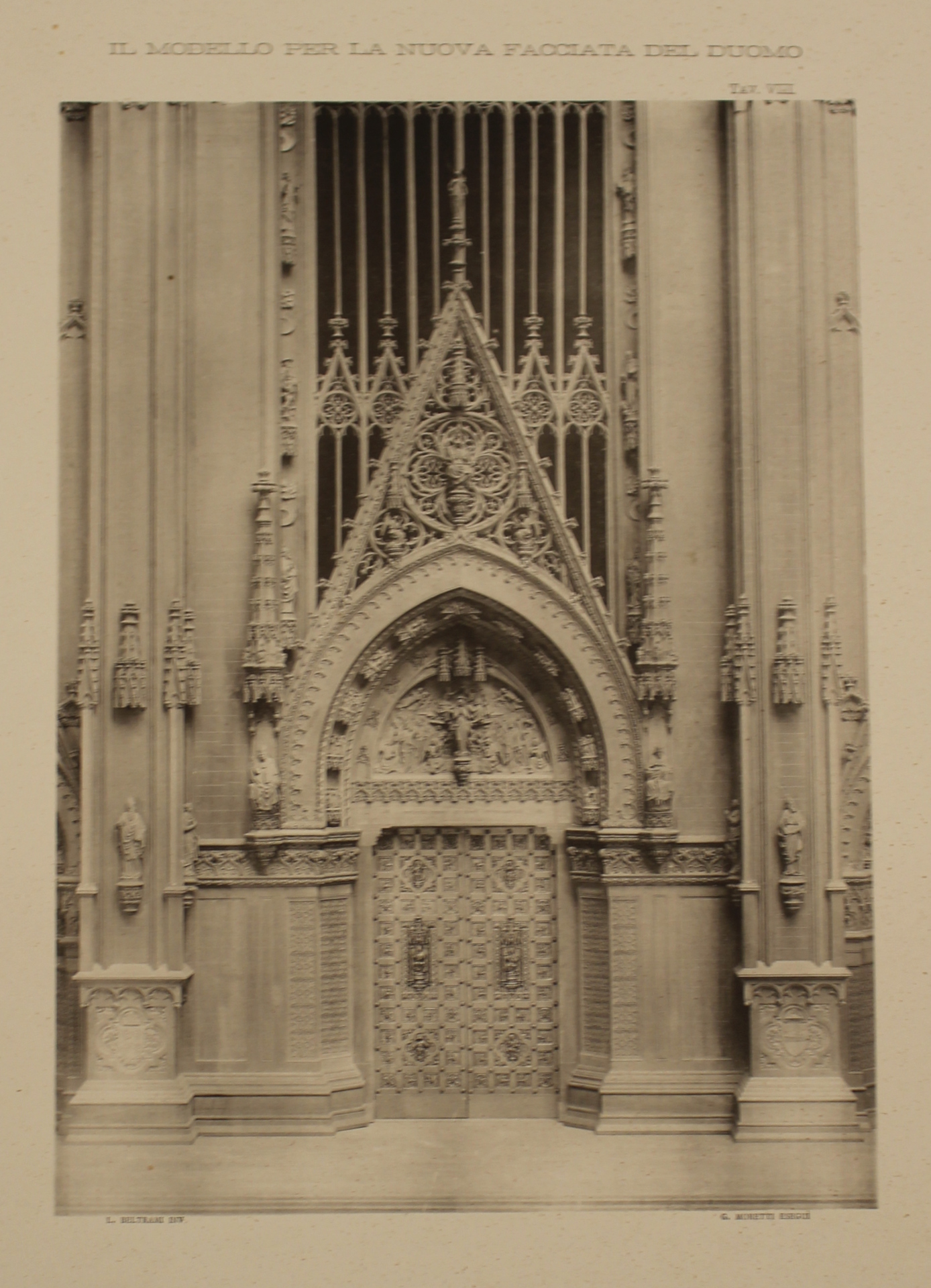

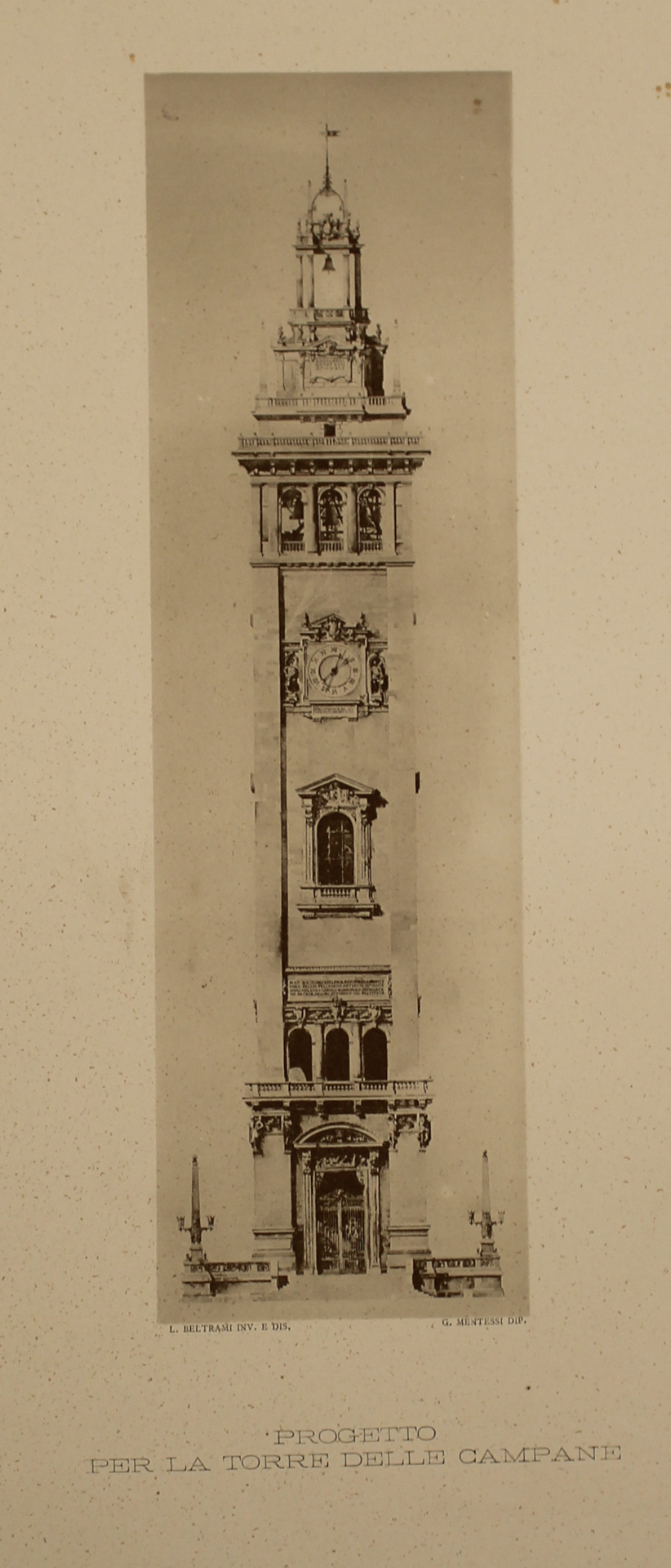

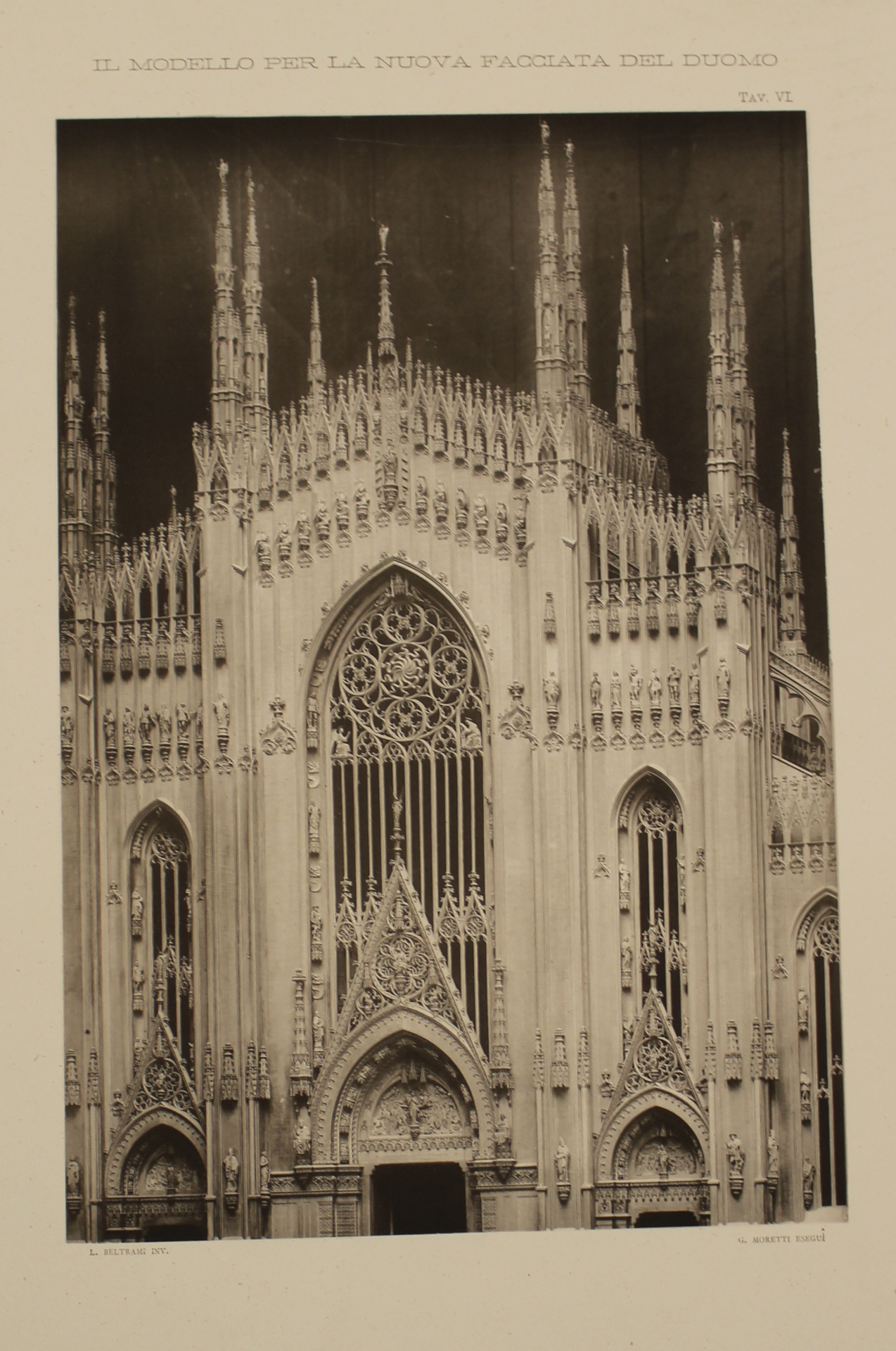

At the end of the 19th century, due to the newly enlarged dimensions of the cathedral square and the monumentality of the surrounding buildings, the question of its façade returned. In 1886, the Fabbrica del Duomo announced a competition in which Luca Beltrami’s proposal emerged. In addition to the study of the façade, he proposed a new arrangement of the square by presenting the idea of erecting a bell tower where the arengario stands today, to be built with the re-use of materials and decorative elements recovered from the demolition of the façade.

Beltrami came second and, surprisingly, Giuseppe Brentano’s project was chosen, but was not realised due to the architect’s untimely death. With yet another competition and project not realised, the idea of a new façade for Milan Cathedral finally disappeared.

Synagogue of Milan

The construction of the synagogue of Milan dates back to 1890-1892, an almost square apsidal building in which elements of Christian religious architecture are present, in the front as well as in the interior, in the oriental references common to 19th-century Eclecticism. Beltrami also designed the furnishings: from the seven-armed lamps to the embroidered curtain covering the door of the Bible storage compartment, to the bright and strongly coloured decorations on the front and, inside, on the gilded apsidal canopy covered with rays of a vivid ultramarine colour.

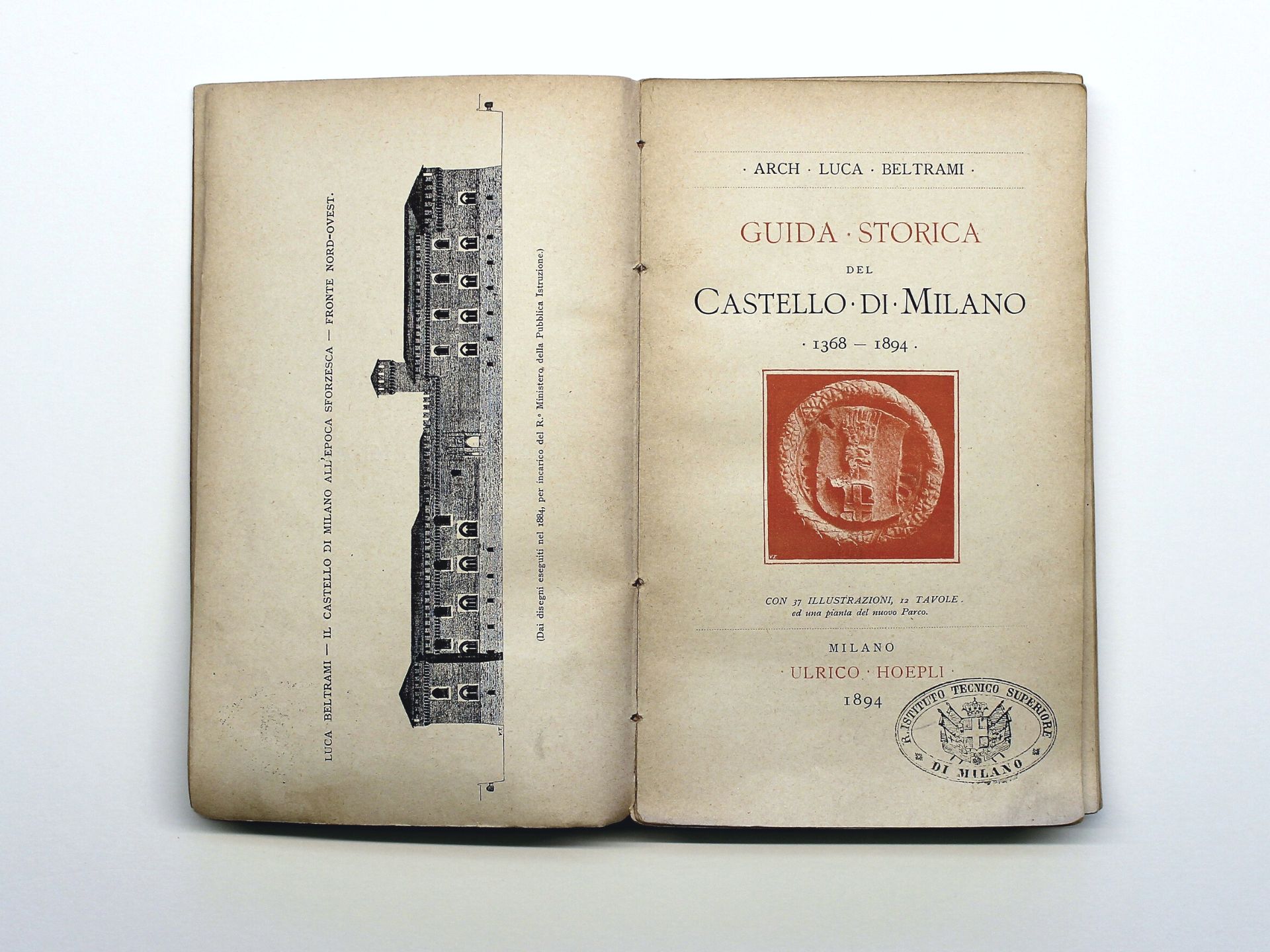

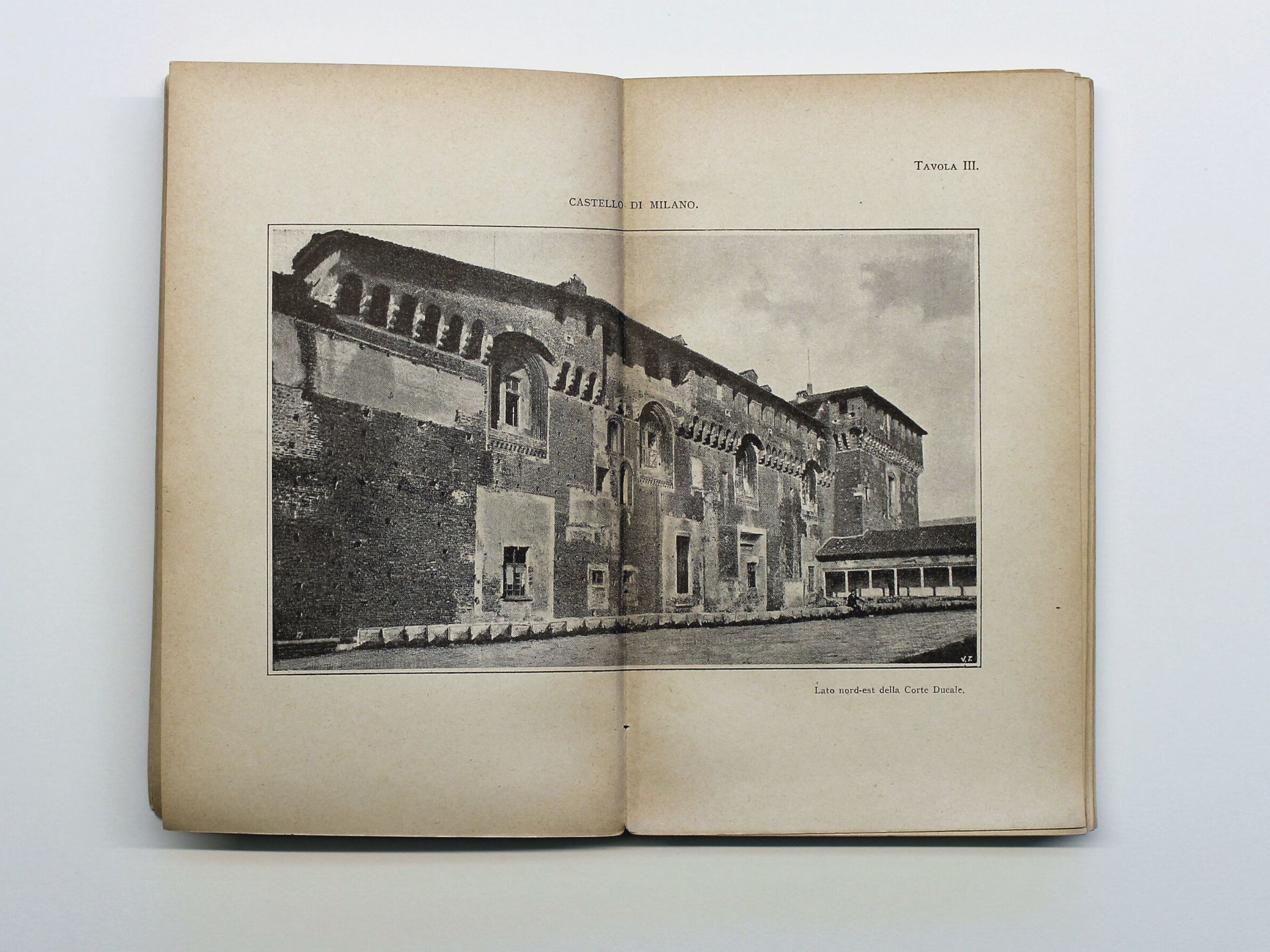

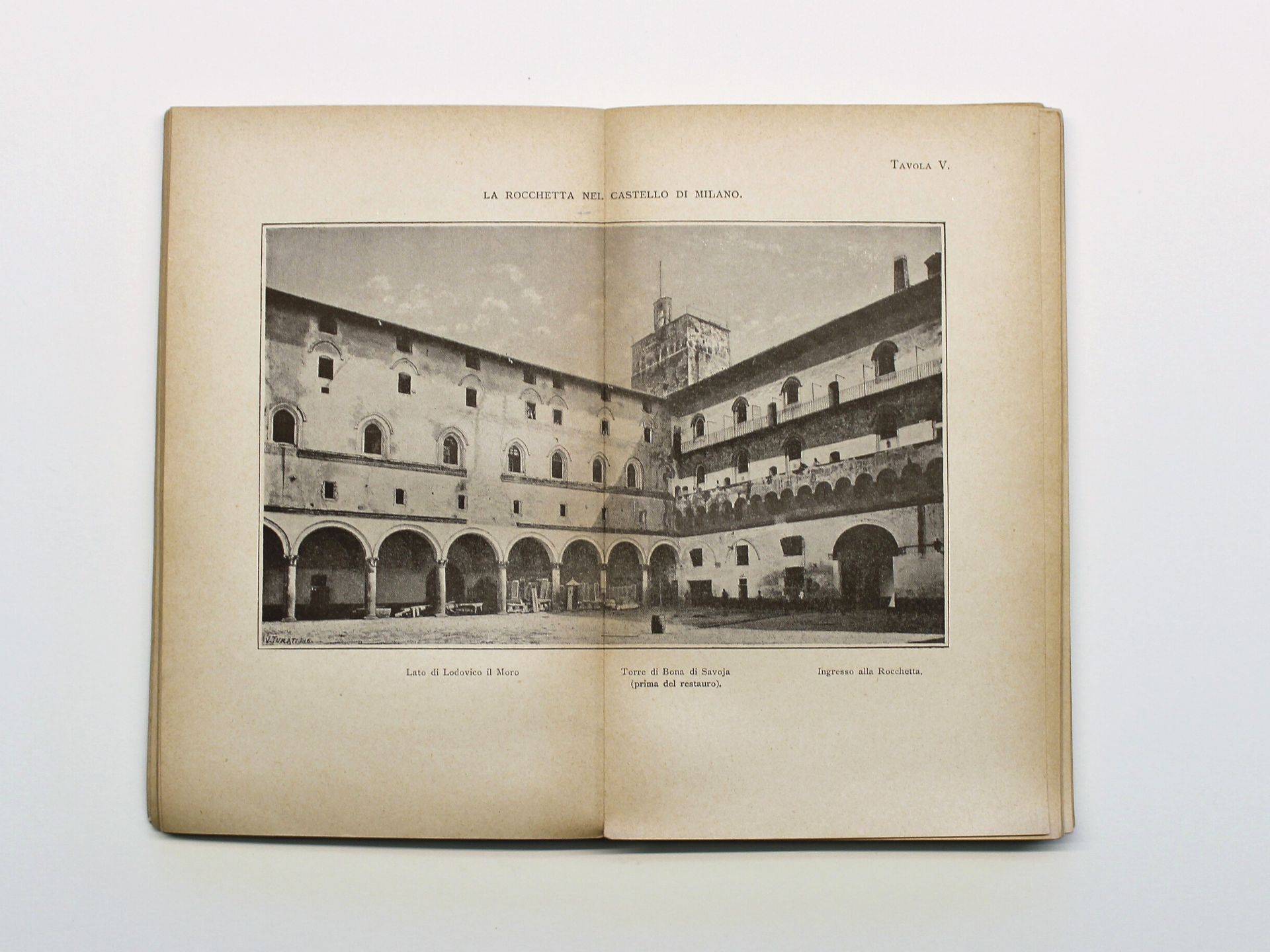

The restoration of the Castello Sforzesco

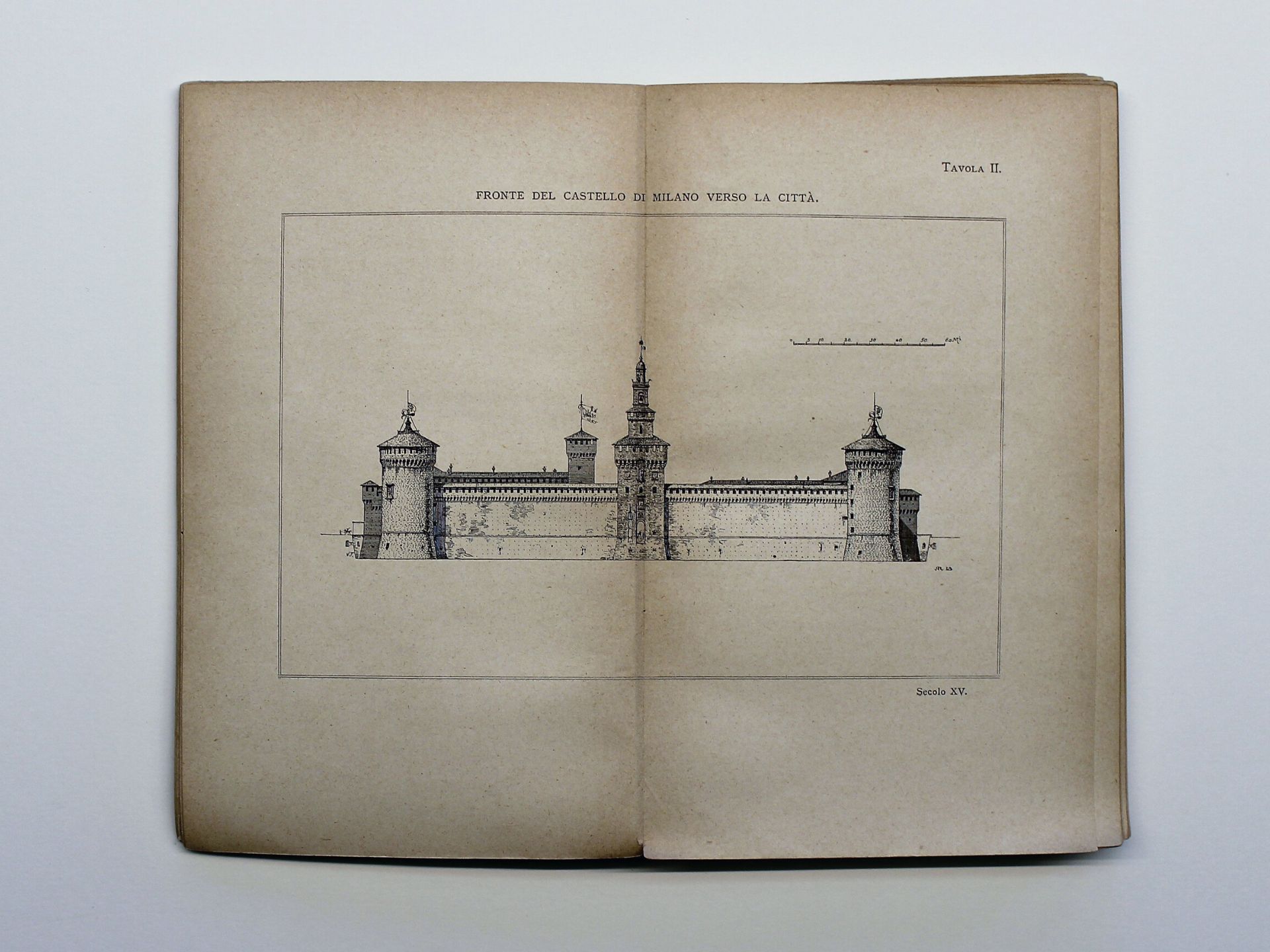

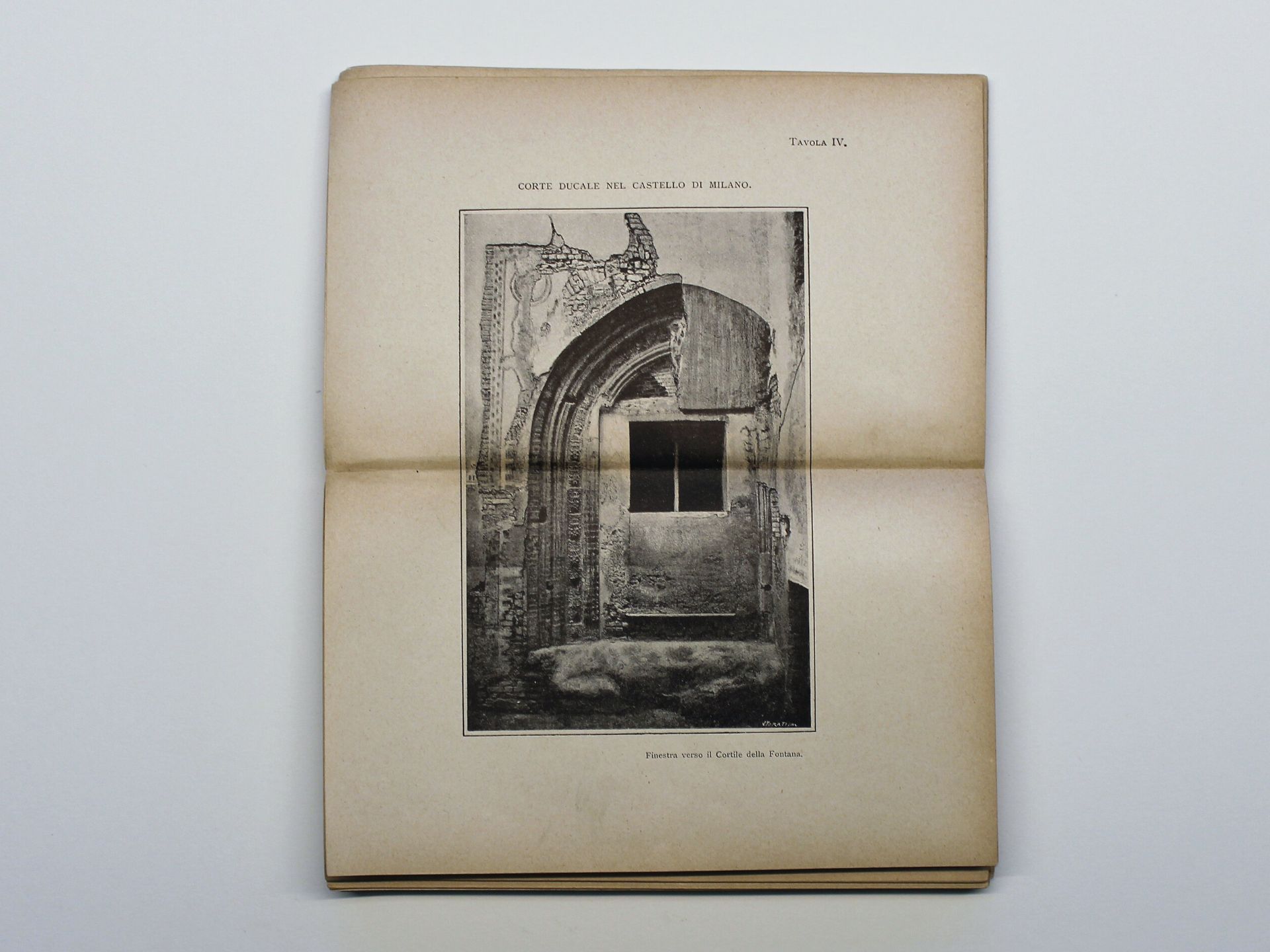

Beltrami’s attention to the urban scale of problems manifested itself in an exemplary manner in the Castle affair. In fact, having abandoned the idea of demolition – after the veto of the Ministry, which intervened at the urging of Beltrami himself and the Commission for the Conservation of Monuments – the Castle became the pivotal element for the realisation of an upper middle-class district of high architectural quality. From this point of view, the bare curtain wall, the two unfinished cylindrical towers, and the modest gateway, were not very decorous. In 1893, the Municipality therefore entrusted Luca Beltrami with the task of gradually recovering the building.

The project he devised and implemented in the following years successfully combined the reasons of decorum, restoration, and – ever important for the municipal coffers – the economy. The incorporation of some of the city’s most important museum and archival institutions in the recovered premises of the Castle constituted a cultural pole that contributed to the overall enhancement of the district. The use of the corner towers, restored by raising the battlements, to house the tanks for the new aqueduct also helped to make the building’s entire recovery more convenient.

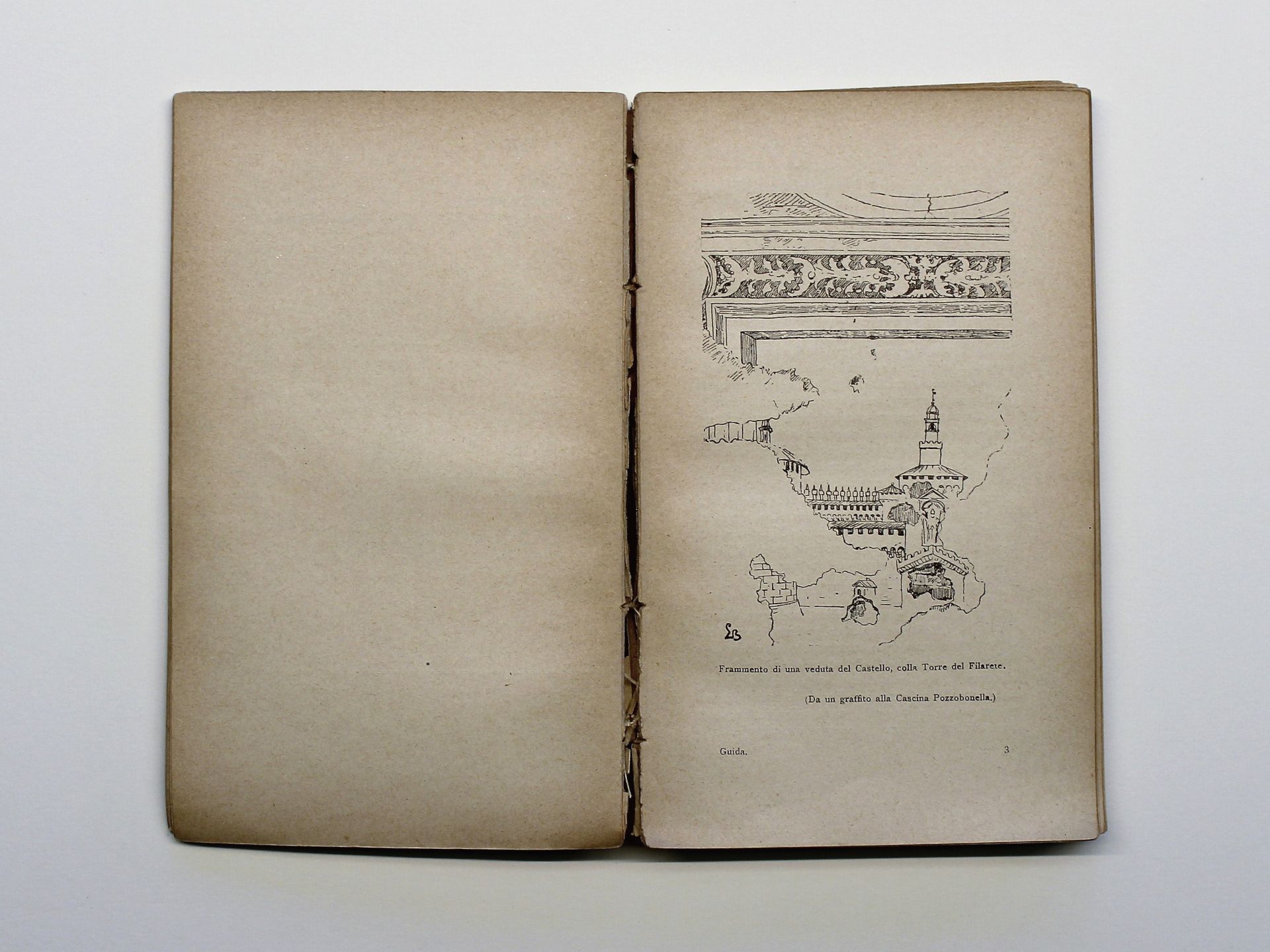

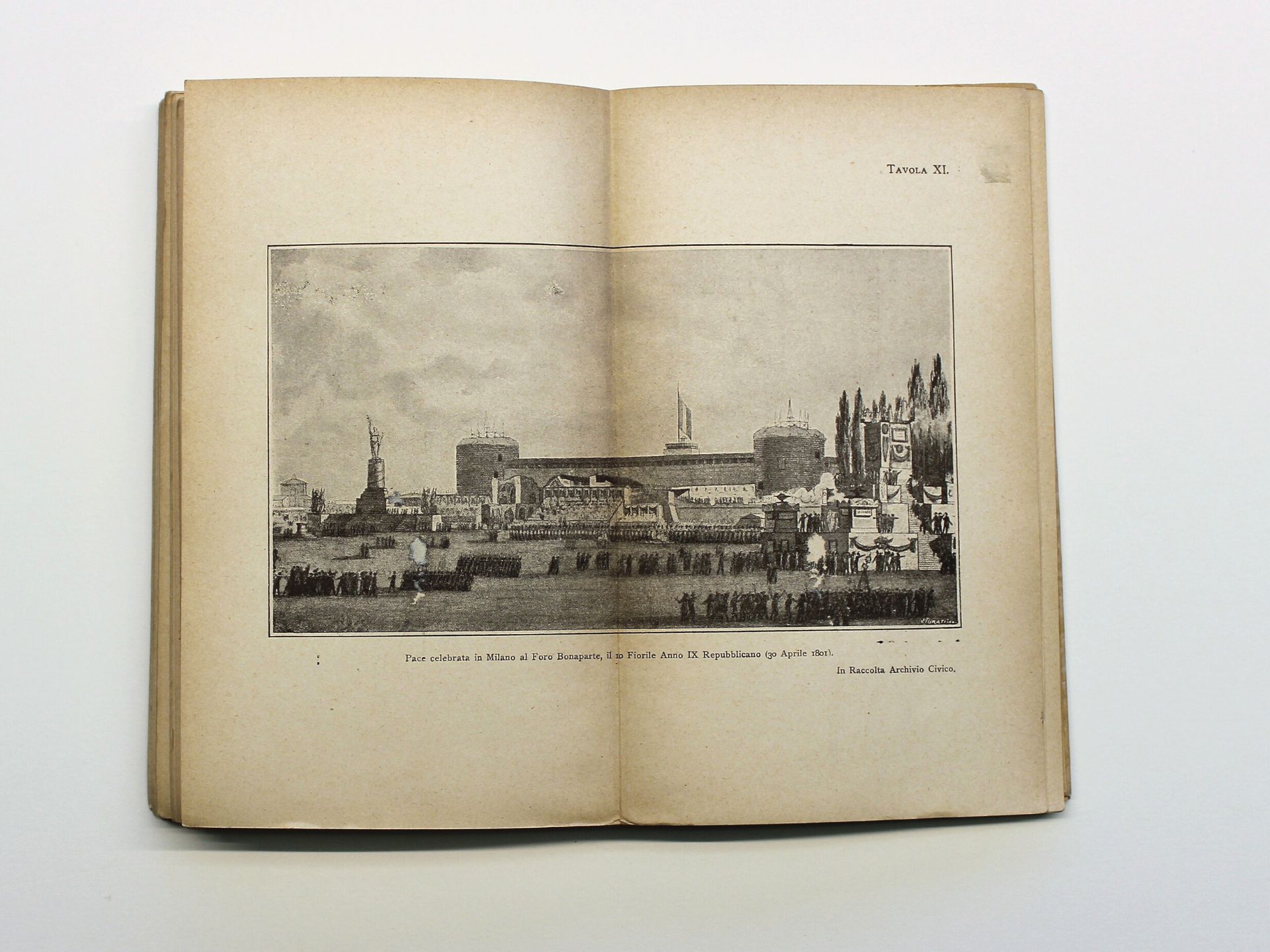

The construction on the city-facing side of the Umberto I Tower, more commonly known as ‘Torre del Filarete’, although highly questionable from the point of view of historical veracity, completed the image of the building and at the same time provided the monumental sequence Cordusio-Via Dante-Foro Bonaparte, which had just been completed, with a worthy focal point.

The new piazza Cordusio

Beltrami still played an important role in the reconfiguration of Piazza Cordusio. This was the point where the streets coming from Piazza del Duomo intersected with Via Dante with a change of direction, forming a triangular widening. Beltrami proposed a large elliptical-shaped square and a new road on the side outlet of the Galleria in order to perfect the complex of works between the Cathedral and the Castle on the basis of considerations of historical topography and road system.

A regulation established an equal height of the buildings and the use of uniform decorations and building materials. Two of the buildings facing onto the square were designed by Beltrami himself, the Casa Riandrà and the Palazzo Venezia of the Assicurazioni Generali company. Of particular note is the case of Palazzo Venezia, which was to form the backdrop to the new elliptical square for views from Via Dante and, at the same time, act as a visual junction of the two access roads towards Piazza del Duomo. Therefore, the building commission, when recognising the monumental character, dictated certain conditions to be respected during construction. Among these, those relating to the mosaic decoration of the median niche and the obligation to raise the central part of the façade with a dome or similar construction of monumental significance derived from considerations of the city’s design and were imposed despite the contrary opinion of the designer, who believed that the continuity of the building’s final lines should be maintained, without any elevations.

The Corriere della Sera building

The headquarters of the “Corriere della Sera” were built in 1903-1904. Beltrami’s ability to interpret the pressing Art Nouveau style immediately fascinated his friend Luigi Albertini, editor of the “Corriere della Sera”, precisely because of the way he combined it with the ‘Milanese common sense’, which was certainly less adventurous in taste.

Precedents are scarce, both in Italy and in Europe. Few newspapers, in fact, have a building constructed to meet the needs of a rapidly changing journalism, especially technological. Later, the project also included the incorporation of the Feltrinelli house, to extend the factory and the building for the rotary presses, which Rosselli would build thirty years later. Other modifications were made by Mariani in the 1930s and 1940s, in perfect line with Beltrami’s project, especially inside the building.

The low, elongated façade already includes an extension in 1907, again embellished with eclectic decorations; a magniloquent language that arrives at a kind of ‘new classicism’, with some concessions to rampant modernism. There is no shortage of references to the Renaissance and the exquisiteness of the Viennese Secession. Beltrami thought of an austere façade where tradition and innovation merged, prefiguring an institutional architecture. On the first floor there is the meeting room, christened Luigi Albertini, with lamps, tables, chairs and shelving designed by Beltrami himself; the editor’s room; the messengers’ room; the archive and the bathrooms. The building, an image of the ‘transparency of information’, is internally well-padded with wood, sober and efficient, destined to become the historical memory of Italian journalism.

Piazza della Scala

The last public space in the definition of which Beltrami played a decisive role is the Piazza della Scala, which, with the exception of Piermarini’s neoclassical building and the Galleria outlet, is entirely due to him, including the design of the street furniture: street lamps and fountains.

Opened in the mid-19th century to emphasise the theatre and as a pivot for connections to the Broletto and San Babila, it is connected to the cathedral by Giuseppe Mengoni’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, which creates an opening that the ambitious Tommaso Marino already wanted to open for his lavish residence.

Beltrami first intervened as councillor, by making his desire prevail to restore the unfinished front of the Palazzo Marino, , which the new space had uncovered in its picturesque ensemble of building curtains that could not satisfy the desire for lavish decorum that was desired for the city. A project, as faithful as possible to that of Galeazzo Alessi, was used, based on historical archive data and the study of the building, according to lines already traced and visible in the façade on Via Case Rotte.

As for the second side of the square, the large project for the construction of the Banca Commerciale Italiana headquarters on the corner with Via Manzoni dates back to 1906. The resulting building is the most ‘neoclassical’ of Beltrami’s designs, combining the highly decorative features of his architecture with monumentality. The formal structure is of extraordinary simplicity, aimed at a modern interpretation of the great 16th-century palazzo, in line with a widespread trend in the most representative Italian architecture, but done here with a particular purity of line.

A choice that likely stems from his desire to place himself in continuity with Piermarini’s classicism of La Scala; from the wishes of the client who aspired to a character of high representativeness; and also, as the critics emphasised at the time of the inauguration, to show himself with a building that harks back to the Renaissance tradition and at the same time to that interpretation of classicism that has taken on the name of ‘Empire’ style.

Sacrificed was the church of San Giovanni Decollato alle Case Rotte, a baroque building owned by the municipality and used as an archive. There was no lack of criticism of the defender of the city’s monuments who, in order to do a service to the patrons, declared the old church to be devoid of artistic value.

The conclusion of the formal design of the square would come with the later, more tormented and less monumental design of the Banca Commerciale Italiana’s second headquarters, towards via Santa Margherita, built after the Great War, in which Beltrami instead took up the lines of Palazzo Marino.