“The data we have available are often representative of a prejudice or in any case of a history that has not been fair to some portions of the population”. In this way Chiara Criscuolo, researcher in the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering of the Politecnico di Milano, explains how the enormous amount of data we have and use, even to make automated decisions, can hide discrimination. We at Frontiere met her to better understand what Data Science Ethics is.

How did your research path start here at the Politecnico?

After a three-year degree in computer engineering, I enrolled in the master’s degree course in Computer Science Engineering. Graduation came with Covid, so I was a bit disoriented about finding a job outside of university. My professor Letizia Tanca asked me if I wanted to stay and do research in the department, with a research grant. I therefore stayed at the Politecnico for two years, first working on a European project involving research institutes (IRCCS) from all over Italy, dealing with the ethical part of this project, which aims to integrate the databases of all hospitals, to do joint research. An example could be to collect data on lung cancer, to study whether the predictive model or analysis used to predict this cancer will be more accurate if shared.

After the first year of research I entered another project, ICT4DEV, a program of the Politecnico di Milano in collaboration with the Eduardo Mondlane University of Maputo (UEM), and AICS (Italian Agency for Development Cooperation) coordinated by Prof. Luciano Baresi. ICT4DEV addresses some of the issues related to the development of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Mozambique, responding to training and skill building needs in a sector that is evolving rapidly and supporting the development of ICT applications in sectors with the greatest impact on development social and economic of the country. Sustainable development is pursued through the training of ICT specialists and support for the creation of a cultural environment that values the use of ICT.

And what did you delve into with your PhD?

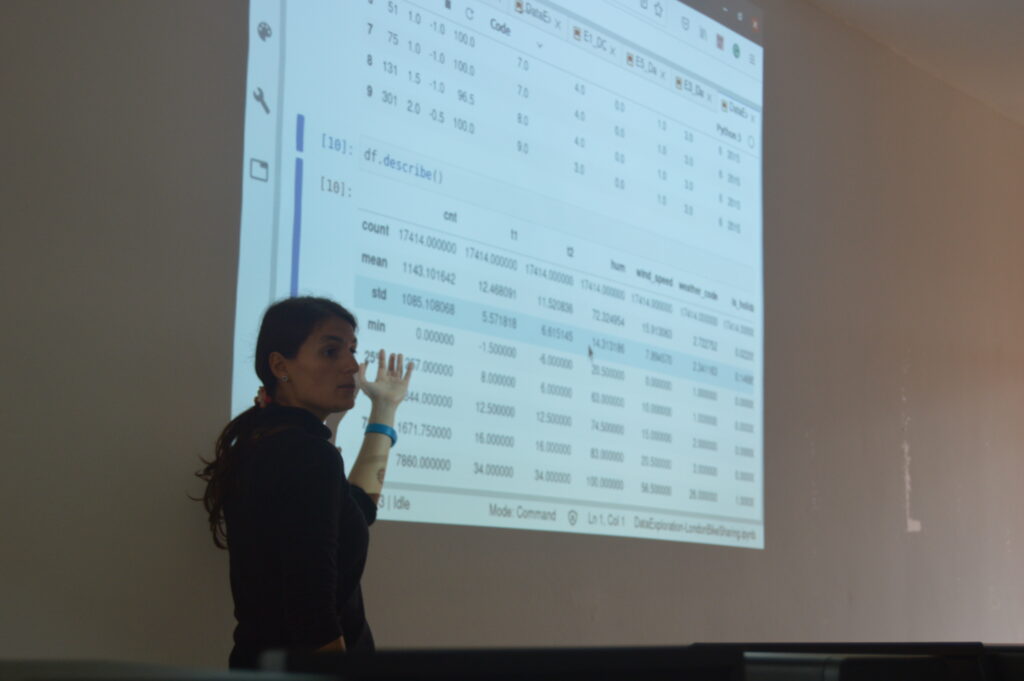

After two years of research grant, I started my PhD, which continued my research that began with my master’s thesis and continued over the years, in parallel with my research projects. My master thesis was entitled FairDB – Using Functional Dependencies to discover Data Bias: based on techniques from the Database and Data Mining areas, concentrated in the field of Data Science Ethics: in particular, the aim was to detect an existing bias in dataset through functional dependencies. In other words, the data we have available are often representative of a prejudice or in any case of a history that has not been fair towards some portions of the population, and the aim is to identify these discriminations through the techniques offered by Data Mining and Databases.

Which ones, for example?

Women, people of color, Native Americans in the US, minorities in general. Through machine learning systems we obtain models used daily to make decisions, choices that impact people’s lives, such as what salary to give an employee or whether or not to hire a candidate. If the set of data on which we “train” the model is biased, i.e. it contains biases, these biases are learned by the model and the resulting decisions are discriminatory towards a group of people. Everything becomes even more critical when the system is completely automatic, i.e. the decision is made without a human being, without awareness of the risks and this is a problem.

How did your research progress?

The last two years I have been working on economic datasets, delving into the issue of wage discrimination. Unfortunately, the stereotype can reside in the data, or in the algorithm in the model or in the decision maker himself. So every little step has its own “responsibility”. If the starting data are stereotyped, the algorithm learns a bias and if the decision maker, who is unaware of this, or worse, leaves the choice to the system, goes on to automate a process that makes wrong decisions, what is obtained is a negative feedback loop where discrimination is perpetrated automatically without realizing it.

Now I’m also working on medical datasets to understand if there are problems in this field as well. The field of health is even more delicate, because all our differences emerge in the medical context: for example, skin cancer is much easier to identify using a machine learning or image recognition system. And it’s easier to recognize it on those with light colored skin. What I’d like to do is a system that makes the user aware of the real potential risk of errors or inaccuracies that a machine learning system has in this sector, because everything happens automatically.

How did this interest in data ethics start?

I wanted to study philosophy at university, but they told me I wasn’t very good at writing; therefore, I started engineering because maybe I was better at maths and I had never done computer science in high school and I wanted to try this new experience. Here at the Politecnico I attended the courses in Philosophical Issues of Computer Science and Computer Ethics by Professor Viola Schiaffonati. This course allowed me to think about what it means to have ethical data, what it means for a dataset to be fair to less representative populations, a dataset that is not discriminatory. All this thanks to my colleagues and the professors of the Politecnico, who allowed me to work in a good research and human environment.

So far you have mainly looked at data from the United States. Is the hypothesis of trying to study European or Italian data more complicated? Is it difficult to find them?

That’s right, it’s hard to find them. What we tend to do now is remove the privacy-protected features and this makes it even more difficult to identify discrimination. I would very much like to study them, I hope that by collaborating with the Italian IRCSS through the medical project I will have more of them, but for now it is a bit difficult also on the health project.

In your opinion, what concrete impact can this research of yours have on society?

I am not a legislator, I cannot make laws. But what I can do is create a tool that shows this discrimination problem in machine learning systems, create awareness in those who use it and try to correct this model, because when I am aware that women and men are paid differently, that people of different ethnicities have different treatments, whether lung cancer is distributed differently in the population, the decision maker can act. Unfortunately the law is the last thing to come. In my opinion, what I can do today is to create awareness.