At the Politecnico di Milano, the proportion of women is also increasing in engineering courses year after year. About time, we hear you say! And we agree. It is a sign of the times and an indication that the stereotypes related to STEM subjects are gradually falling one after another.

The Frontiere team therefore wanted to introduce you to some young women engineering researchers, who can tell us about their experience in their academic career here at the Politecnico.

We were a little spoiled for choice, but we knew that one sure hit was LaBS, a cluster of laboratories in the Department of Chemistry working on the mechanics of biological structures. Here, there is an evident female presence, probably also due to the historical preference of female students for biomedical engineering, among the various areas of engineering. But this too is a preconception that we will debunk in the course of our story.

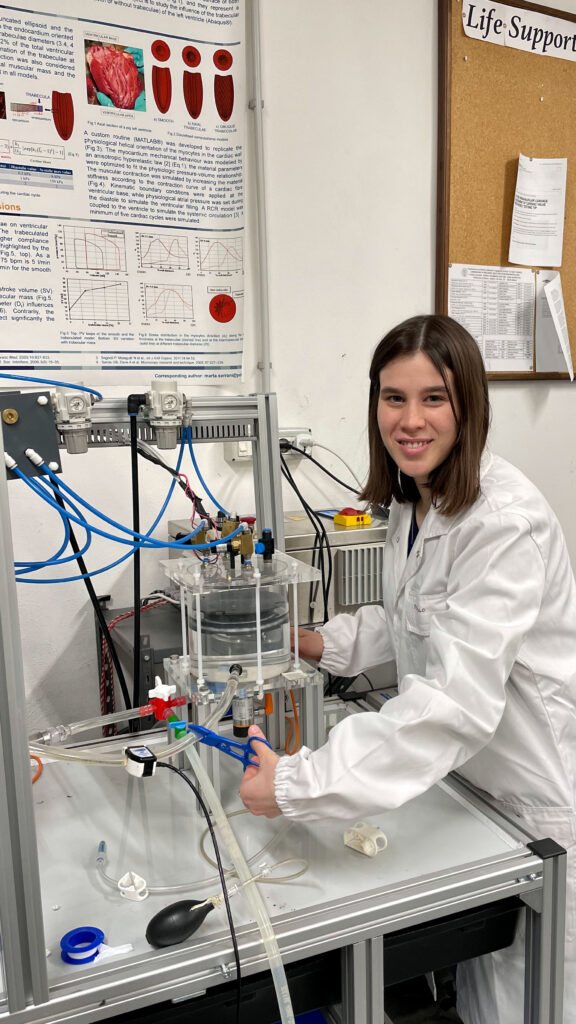

Professor Maria Laura Costantino, head of the Artificial Organs unit, welcomed us into the laboratory. But our researchers come from all over the LaBS’ souls: Artificial Organs (internal organs, valve prostheses, life support systems, specific patient models), 3DB & STM (3D bioprinting and soft tissue mechanics), CompBiomech (computational biomechanics), Mechanobiology, MeDBioMech (biomechanics of medical devices), μBIOmechL (micro biomechanics) and μFLUID (micro health devices).

Our visit was also an opportunity to compare two generations of researchers. Here you can find Maria Laura Costantino’s story of her professional career, between gratifications and overcome obstacles.

The researchers

Ilaria Rota and Ilaria Guidetti are the youngest of the PhD students in bioengineering, in their first year. Federica Potere and Francesca Danielli are halfway through their course, while Beatrice Belgio is in her third year.

Francesca Berti, on the other hand, is a postdoc temporary research fellow, because she already has got a PhD, in her case in Materials Engineering, but still in the field of biomedical applications.

They all have a degree in Biomedical Engineering, the equivalent of a BA and Master’s, here at the Politecnico.

Ravipati Priusha did her Bachelor’s Degree in Biology in India, earned her Erasmus Mundus Joint Master in Nanomedicine for Drug Delivery in Europe, and is now in her first year of a PhD here with us.

Finally, Victoria Yuan, after graduating from Stanford, is here thanks to a Fulbright scholarship.

What has been your academic career and what are you currently researching?

BB: My journey in the world of research began with my Master’s thesis in the United States during eight months. There, I worked in two research laboratories: first at the University of Pittsburgh and then at University of Pennsylvania and at the Children Hospital of Philadelphia, one of the best children’s hospital in America. My field were regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, which I was very passionate about, so I decided to continue in my PhD course. Now I am focusing on regeneration of ocular tissues, and the development of models of the retina in laboratory to evaluate alternative therapies to treat various ocular pathologies, including maculopathy.

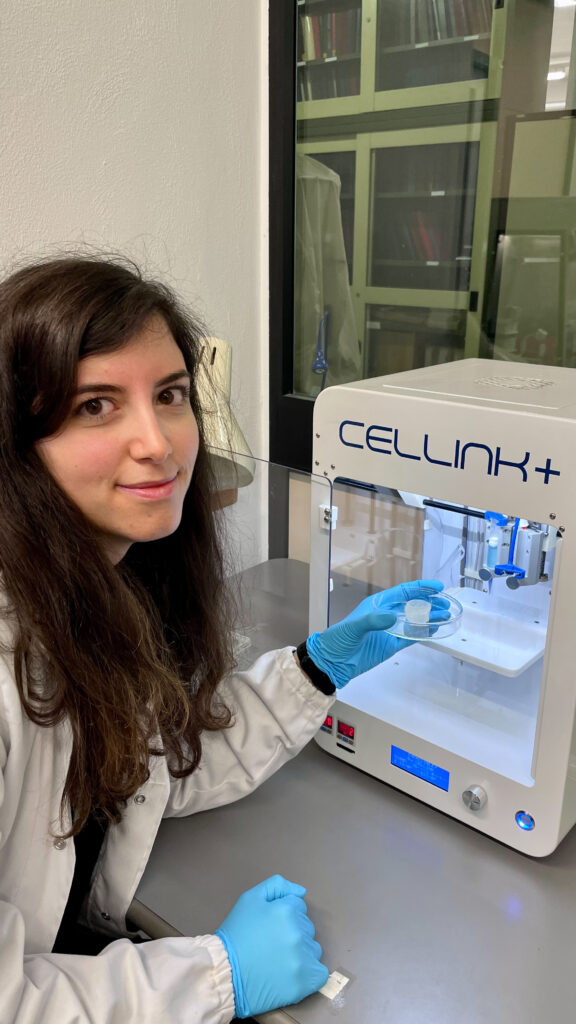

FP: I too did my Master’s thesis in the USA, at the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond, Virginia, where I studied new materials for vascular prostheses. Once I graduated at Politecnico di Milano, I was then hired by VCU as a researcher. In 2020 I came back to Italy and started my PhD here, where I work on the 3D bioprinting of tubular constructs, specifically aorta and trachea.

FB: In my PhD, during which I spent six months at MIT in Boston, I worked on a particular shape memory alloy, Nitinol, a very useful material for minimally invasive devices, such as stents and valves, which are implanted without invasive procedures, such as open-heart surgery, which have much longer recovery times. My PhD in Materials Engineering therefore involves fairly cross-cutting research and enables me to touch on all the particularities of the materials used in bioengineering, both at a numerical and experimental stage, passing through very different clinical applications, such as cardio-vascular and orthopaedic ones.

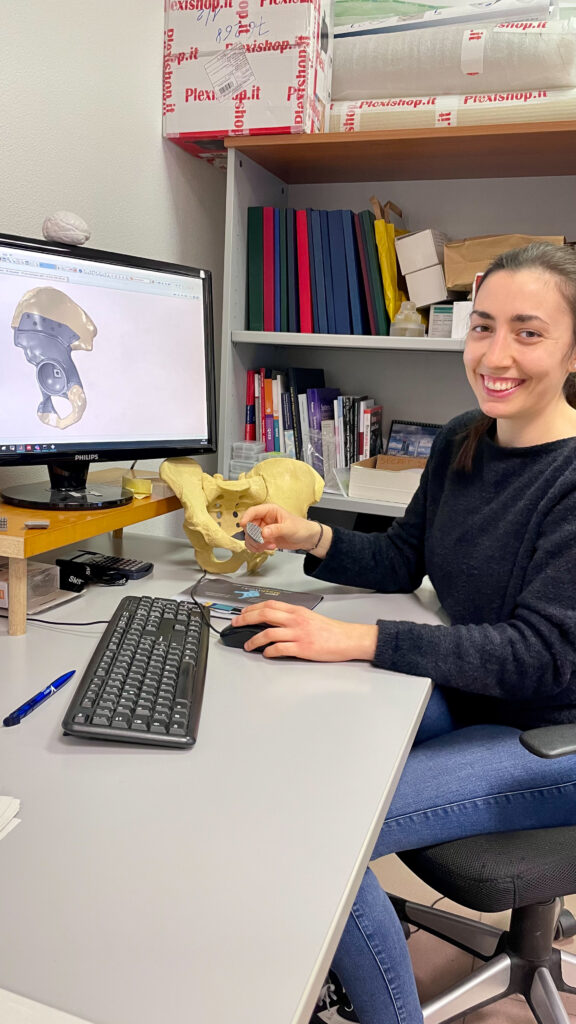

FD: My experience at LaBS, began with my Master’s thesis on the cardiovascular system, about a Nitinol device to treat an anatomical site near the left atrium (the left atrial appendix) in patients suffering from atrial fibrillation. On the contrary, my PhD project concerns a totally different field, orthopaedics, in particular 3D printed endoprostheses, such as the pelvis or ankle. Despite their different application fields, the two projects have provided for both an experimental and numerical approach. To date, the numerical study has proved to be a tool of fundamental importance, for example in supporting the surgeon in the preoperative phase in the choice of the optimal device and implantation modality.

VY: I studied biomedical calculus at Stanford and for my dissertation I focused on the Berlin Heart EXCOR, which is a ventricular assist device for infants and children with heart failure. Now, I am continuing my research on the Berlin Heart EXCOR here. For nine months, I’ve been working on a mix of experimental and computational methods to understand how we can use it to support babies born with only one ventricle.

RP: I did my Masters in the field of nanomedicine for drug administration, researching the design and synthesis of vehicles for administering drugs. My PhD is on the Marie Skłodowska-Curie medical project DECODE, where I am working on the creation of artificial atherosclerotic plaques in the arteries, to test the performance or effectiveness of the drug-coated balloons that are normally used in hospitals to treat atherosclerosis.

IG: I am currently working on the development of a ventricular assist device for the right side of the heart. At the present time, we are using computational methods to optimize the design of this device, to then evaluate the degree of haemolysis, i.e. damage to the red blood cells. We will subsequently validate this model through various experimental tests.

IR: My PhD is about the design of patient-specific maxillofacial devices. In particular, my project is related to the optimization of thickness and shape, for example of osteosynthesis plates, which are used to help repair bone fractures. Another aspect on which my work focuses is the study of the degradation of plates into biodegradable metals, such as those in magnesium alloy, through numerical simulation.

Why did you choose this path? Is there an aspect that particularly appeals to you in your research?

BB: I was undecided between medicine and biomedical engineering, but I chose the latter because I think that, by researching therapies or drugs, I will be able to help more than a single patient. It’s an idealized vision of research, it’s not that easy to achieve these results, but that was the motivation. I like looking for solutions to people’s real problems.

FP: Medicine has always been part of my daily life: my parents and my brother are doctors. From an early age I was attracted to the idea that my studies and my work could improve the quality of life and health of people. During my studies I developed an interest in the disciplines of the mathematical-technological area that study and propose innovative ways to solve problems: biomedical engineering seemed to me the perfect combination that encompasses all the sciences. I chose the cardiovascular field, because I really like the heart as an organ, the concept of blood that circulates and nourishes the whole body.

FD: My options were biomedical engineering, medicine, or philosophy, which I loved because of its degree of abstraction and the desire (maybe utopian?) to find answers to “existential” questions. In the end, reflecting on career opportunities, I abandoned that idea. I initially attempted the medicine test and failed. With hindsight, thinking, this “defeat” proved beneficial. I believe that the doctor’s work presupposes establishing an empathic relationship with the patient in order to identify the best cure. This aspect was incompatible with my introverted character. It will seem obvious, but to date the choice of biomedical engineering has not yet given me any reason for regret, otherwise I would not have chosen to pursue the PhD in bioengineering.

RP: In high school, I learned about molecular biology, and it really interested me how a small change in a molecule can affect an entire person. I chose biotechnology to study how technologies can change humans. I’ve always been curious, and I think it’s always a good feeling to be capable of having an impact on people’s lives. This is exactly what I want to do, through my career that started as a biologist, travelling through nanomedicine and is now engineering.

FB: I was very undecided between mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering, and i surely chose with not much awareness. At the end of high school, I didn’t really know what bioengineering was, but along the way I realised that it was perfect for me: bringing together engineering and creativity, but also helping others and innovating from all angles.I have always loved science; I define myself as a creative person, so I am completely at home in design.

VY: I chose biomedical computation because I have always liked maths. Even as a small child, my father played maths games with me. I realized that there are many applications of mathematics, especially in biology, in cardiovascular system. It is also a way to help other people, which is why I chose to study paediatric cardiology. At Stanford, I worked in the hospital where I met many families of children with heart disease. This made me want to explore new technologies in this field, and this is what brought me to the Politecnico. After the Fulbright scholarship, I will return to the United States to continue with medicine and engineering.

IG: During my fourth year at high school, I began to get information about the various university degrees, but I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. Luckily, at the Open Day at the Politecnico, I discovered biomedical engineering, which I had never heard of before. I was especially interested in the link with sport, as I practised judo then. To introduce us to the subject, they also showed us sports prostheses, which definitely surprised and convinced me. Along my path I started to work in the cardiovascular area, thanks to my theses and my projects. What I really like is the research itself, discovering new things and not surrendering to difficulties, because when you find the solution, you get much satisfaction.

IR: In high school, I loved maths, physics and biology, so I sat the admission test when I was in the fourth grade. Among the engineering preferences I didn’t put biomedical, but electronics and computer science. In the fifth grade, I did a thesis on the application of differential equations to medicine and biology. From there, I realized that I liked engineering applied to the fields of medicine and biology, so in the end I enrolled in biomedical engineering and I am very happy with this choice.

Have you encountered any difficulties on your path? A moment in your university career when you said to yourself: “I’ve had enough, I’m giving up”?

BB: No, it has never crossed my mind. Difficulties? Yes, actually not quite during the PhD course, more during the thesis. I went through a difficult period, in which, because of an unpredictable event, I was asked to equip a new laboratory from the start. At first, this thing destabilized me a bit, but in retrospect it was an opportunity to test myself and acquire new skills different from those of the normal undergraduate. The love for my job, the passion that I put into it, helped me to overcome that time, strengthening my will to go through with my PhD.

FR: I never thought of giving up: certainly, as a student, there can be times you feel discouraged, but for me this is what also drives me forward and make the leap in quality. I look for the positive aspects even in these difficulties, to grow and improve myself. Research is a constant challenge between yourself and the state of the art: that’s exactly what I like. Even if the path is often uphill, it allows you to reach and realize what you have imagined and designed with study.

IR: Honestly, me neither, I have never thought “I’m giving up”, I’m giving up engineering, because I feel that it is a path that is truly mine, what I am meant to do.

FD: Give it all up? Only at my first university exam. If I think back to that moment now, it just makes me laugh. During the period between graduation and the start of the PhD, between December 2019 and October 2020, due to the pandemic situation, I was worried about my future in case they didn’t accept me onto the PhD course. Would I have to start looking for a job in a critical situation such as during the early stages of the pandemic? At that point, I stopped to reflect on a possible plan B.

RP: Quit? No. Actually, I usually get bored of things very quickly. But I think the profession and research are a little different: they are more suitable for me, because even if I get bored, there is always something new to discover.

FB: I never thought about giving up my degree. Actually, my perfectionism becomes a challenge with myself. During my PhD, I had a moment of crisis, probably due to the switch from biomedical engineering to materials engineering. I was back in the game; I had to study subjects I had never seen before, at a much higher level of competition, where you are already required to have the knowledge. Then I went to Boston and all my doubts vanished.

VY: But I never thought about giving up research, because for me research enables you to ask yourself so many different questions. You can always explore new ideas and situations and help people, especially with biomedical engineering. I thought about returning to the United States for a PhD in medicine: it would have been 14 years of training! I thought about the fact that I would start working when I was about 40 and I didn’t know if I wanted that. But every time I think about quitting medicine, I am reminded of all the children, families and patients I met when I was volunteering with the clinic, and I think that this is what it means to help other people. Maybe I’ll have to wait until I’m 40 to get a job, but until then I’ll be able to help as many people as possible along the way.

IG: As a student, I never felt the need to change what I was doing. Indeed, probably in all the crises I had in that period, the only certain thing was that I liked what I was studying. LaBS, where I was lucky enough to start this career, is an environment that helps you a lot. There are a lot of young PhD students and researchers here: you know you are not alone; you meet people ahead of you in the same career who have gone through the same fears and overcome them. Even the professors who supervise you, you always have someone who can guide and support you when you need.

What do you think of the gender gap at university? How did you find it, as a woman in the field of research, compared to your male colleagues?

BB: Let’s start with the fact that I am lucky enough to have two female “bosses” and a female tutor; two positive examples of exceptional professors, researchers and women, role models that remind me that it can be achieved.

Unfortunately, it still happens too often to be called “Miss Belgio” rather than by my title of engineer, which is belittling. In our laboratories and biomedical engineering courses, the presence of women is increasingly numerous, so the gender gap is less evident. But when we move to different areas, for example mechanical engineering, where ther is still male predominance, there is a different consideration and a paternalistic attitude on the part of some male interlocutors.

IR: There are also difficulties along the way; perhaps male university classmates who sometimes think that women can’t do certain things. But fortunately they are few.

Another thing is that when you are in your early university years, most of the professors you meet are men; then slowly you begin to see more women. In reality, now things are changing: on my course, we were almost half women and half men, while on other courses the ratio is still very disproportionate.

IG: Indeed, looking back above all at my Bachelor’s degree, I remember nearly only male faces. This is a little daunting, especially when you want to consider what you want to do after graduation and your PhD.

FP: I am fortunate to work in a team of women; in fact, my reference teachers are women and I have their good example to follow. There is certainly a difference in attitude towards a woman. It is more difficult to assert oneself even in thought, it is as if every concept expressed by you must be demonstrated, and the interlocutor must be convinced. It happens in historically male-dominated places like workshops, they treat you with condescension. They may seem nonsense, but in everyday life you still have to deal with it, and it can weigh on you.

FD: I have never experienced this gender difference first-hand, but once. Some colleagues and me had to do some experimental tests in a certain laboratory. The technician, responsible for the experiment set up he did not address us well, responding abruptly to our questions and observations.

FB: We are sure that he would never have dared to behave in such a way with male researchers. And I am a post-doc researcher, so I took the liberty of pointing out his attitude to him; however, when you are still a PhD student, you never know how to react.

Back in the day, I too had a very bad experience at a mechanical engineering oral exam, where there were two of us in a row, a guy and me. The guy was asked for his name and surname, and he was given 30. I started with 28, I spoke for an hour, and when I stopped to breathe, I was told, “Miss, you can’t have any hesitations on this subject. Consider yourself fortunate that I let you keep 28 and you can go.”

Now, someone like me just forges ahead and doesn’t care. But for other people, not necessarily because they are weaker, but precisely because they are just at the start of their career, it can be difficult to decide how to deal with figures like this. It is very disheartening, because you never know if it is because you are a woman or because it’s you. And it’s horrible to have this doubt.

FD: Even these myths that circulate about mechanical engineering as an all-male course… The female ratios are getting higher, and spreading these stereotypes also discourages women who would like to take that programme.

RP: I have not personally experienced any gender gap in the places I have been so far, probably because I come from a non-engineering background, where I have always seen more women than men in the laboratories.

VY: When I was working in medicine, the ratio was realistically 50/50. However, in computer science or electrical engineering courses, most of the students were men, many of the assistants were men, as were most of the professors. As the courses got more advanced, the number of women got smaller and smaller. What helped me was having many women who have been role models for me. My tutor at Stanford, Professor Marsden, is a woman, and she is also a mother and wife and runs a very successful laboratory. She has been a great mentor to me, and has always encouraged me to do engineering regardless of gender.

How do you see yourself in the future?

BB: The hope is to stay here at the Politecnico, an avant-garde and frontier environment, continuing to do research in a role of increasing growth and greater responsibility on a par with my male colleagues.

IR: I’m not sure yet. I have only recently started my PhD, so for three years I’ll be here, and then we’ll see. I think that over time I will understand what I really want to do; whether I want to stay in a university or go to work for a company, in Italy or abroad.

FP: I would certainly like to stay in the field of research, because it always stimulates you to grow, to discover new things. The Politecnico would be perfect, given that it is such a great place to be, which has raised and formed me. One day, I would like to be able to say that I have contributed to a discovery, sought to improve some aspect that I am studying in the field of regenerative cardiovascular and tissue engineering.

FD: I have absolutely no clear ideas about what to do after finishing my PhD. I have no doubt that I would like to stay in the research field, but at university or with a company? Having never tried the experience at a company, I would like to find out about this world too, to understand where I want to go next.

RP: After my PhD, I would like to gain work experience with a company, because I have never worked at a company and I would like to know how it feels. Also, I would like to go back to India, because I want to create something there, where there are so many things to improve. Since I have lived in Europe, I clearly see what is missing in my country in terms of medical facilities, in terms of research and more.

VY: Apart from the long training I mentioned earlier to become a doctor, as a PhD student I would like to teach computational biology or engineering, because I would like to have my own laboratory and create new medical technologies for children, as well as mentor other students, especially women, ensuring there are more and more women in engineering. I see my future in the United States, although I hope I can still be involved in lots of international collaborations, because I think research is better when we all work together globally.

FB: I actually started my PhD with the idea of becoming a university professor. So, my dream would be to stay in academic research, but the teaching component is something that I’m very passionate about. I was lucky enough to be a practical teaching assistant from the first year of my PhD and thus spend time in the classroom: there is a strong involvement with the students. Someone may be frightened by it; on the contrary, it really motivates me. The goal is, yes, personal fulfilment, but through this dialogue, this relationship with the students, transmitting my knowledge and not “keeping it all to myself”. A kind of role model that provides infinite gratification and at the same time can be a strong motivator for my students.

IG: Today I did my first practical teaching exercise, so I feel very close to what Francesca was saying, because it’s something that has always attracted me, the teaching part. I don’t know if it will actually be what I want to do, it certainly engages me a lot, both how we do it here in Italy and how I had the opportunity to see it abroad. It would be nice to be able to integrate certain elements of the various methods by which it is taught in different universities, with their pros and cons. In research, my hope is to see the device I’m working on actually finished, functional and usable. It would certainly be a great satisfaction.