We met Serena Benelli while she was doing her PhD in the Gallone Archive of the Department of Physics. We went to see her and she showed us hundreds of tiny samples from Leonardo’s Last Supper, first preserved in resin and then stored in neat little boxes. We were looking at a real treasure, safeguarded by the Politecnico di Milano. But Serena has gone deeper: we’ll leave it to her to explain!

Serena, we know that you obtained a doctorate in Architecture, Construction Engineering and the Built Environment, and then went on to work in the Department of Physics, more specifically in the Gallone Archive. But let’s start from the beginning: what brought you to the Politecnico?

It was rather by chance, because my previous studies were in the humanities.

I took a degree in the History and Criticism of Art at the University of Milan, and then went on to do a Postgraduate Specialisation in Historical and Artistic Heritage at the same university. It was during the two years of my postgraduate course that I discovered the existence of the Gallone Archive, and began visiting this part of the Politecnico. A fortuitous turn of events, now I look back on it.

What brought you to Leonardo?

One of the courses offered by the school was in Museology and Art Criticism and Restoration, and was being conducted that year by Michela Palazzo, the then director of the Museo del Cenacolo Vinciano.

My interest in the exciting efforts to conserve Leonardo’s work, which we discovered during our encounters with Professor Palazzo, led me to ask if I could do an internship at her office, which is part of the Lombardy Regional Museums Directorate. She accepted my request and offered me an important project for my internship: the creation of a “Multimedia Archive for the Museo del Cenacolo Vinciano”. She asked me to work with the Department of Physics of the Politecnico, and to undertake the task of re-organising all the material produced by Antonietta Gallone’s work and stored in the archive of the same name. I was therefore able to look through the various papers in the archive, and to create an initial index of the documents related to the Cenacolo.

So, when did you get the idea of doing the doctorate?

The following summer, I took part in a tender for an interdepartmental research project, aimed at studying and upgrading the samples in the archive, with Leonardo’s Last Supper as a case study.

That’s how I began the project for my doctorate, working under the supervision of Stefano Della Torre and Ezio Puppin. Ezio is in charge of the Gallone Archive, and is the real “custodian” of the memory and materials of this scholar. The title of my thesis was “The Gallone Samples Archive: Knowledge Management Through Time. The Last Supper Collection Online Information System”.

Tell us about the Gallone Archive.

Before describing the Archive, I first need to say something about the person who created it, Antonietta Gallone.

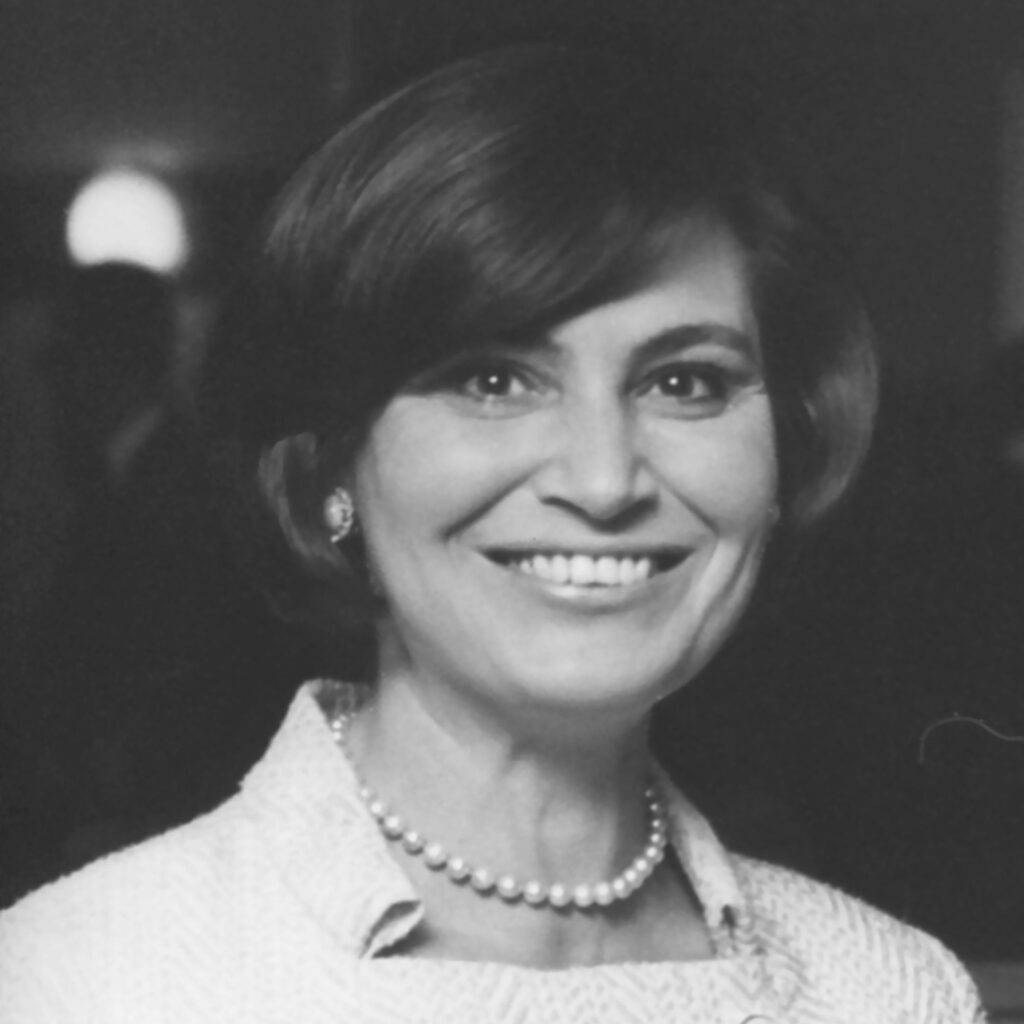

She was born in 1928, and was one of a handful of women to study physics in the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Milan, graduating in 1951. Shortly afterwards, she took up a research post in the Institute of Physics at the Politecnico di Milano, remaining there until her retirement.

Antonietta Gallone was one of the first women in the Post-War period to apply a “diagnostic” approach to our cultural heritage – to use a medical term. Indeed, from the mid-1970s onward, Gallone focused on the application of “physico-chemical” methods to the field of conservation. Throughout her scientific career, she showed a considerable knowledge of the history of art and artistic methods. She insisted on the need for analysts and lab technicians to be trained not only in materials science, but also in artistic techniques, and was keen to promote dialogue between historians, restorers and scientific experts, encouraging a multidisciplinary approach. She was thus a pioneer in the way she defined the professional role of those we now call conservation scientists.

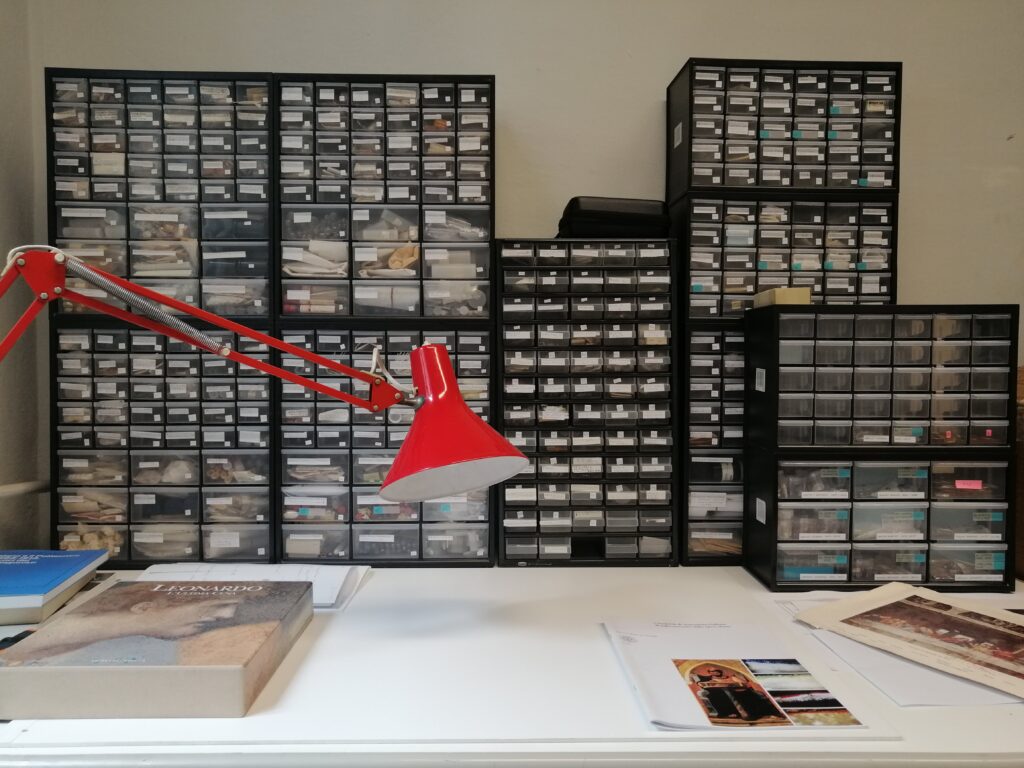

In this historical context, Gallone mainly carried out micro-destructive analysis, using microscopic samples taken from historical and artistic artefacts. So, the archive was built up as a result of the efforts of Antonietta Gallone, who spent about three decades working on the use of diagnostics in relation to our cultural heritage.

What are the contents of the archive?

It contains about 600 scientific reports and about 12,000 samples, associated with the analytical tests carried out by the physicist. Antonietta Gallone’s huge body of knowledge has been very useful, and will continue to be so, helping to improve our understanding of art history and artistic techniques. It was used to restore many masterpieces in the second half of the twentieth century, such as Leonardo’s Last Supper at Santa Maria delle Grazie, and Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel, to mention a couple of important sites, which saw her working together with the famous Milanese restorer Pinin Brambilla Barcilon.

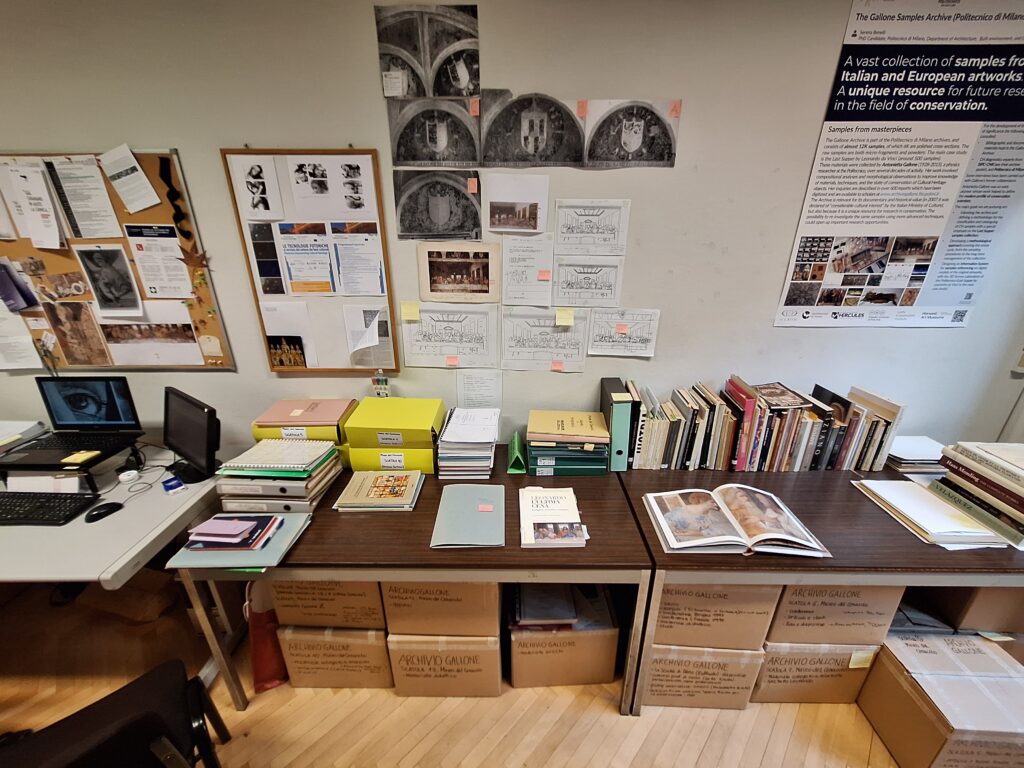

More in particular, the Gallone archive is basically divided into three sections: the “Reports” section consists of typed diagnostic reports, produced during the analytical tests carried out by the physicist from the mid-1970s on, which have already been digitised. Each report contains observations and comments about the results of the analysis, highlighting the most important data.

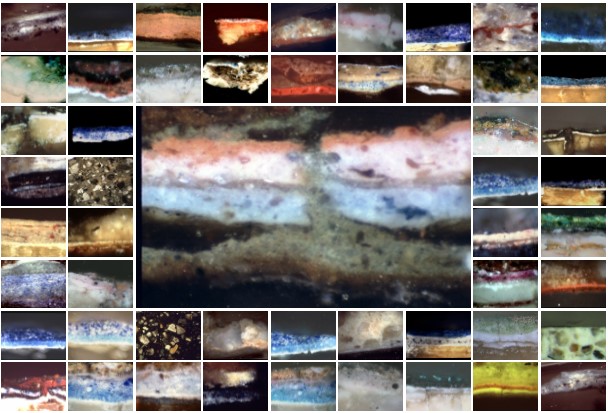

Then there is the collection of “Samples”, consisting partly of stratigraphic sections and partly of micro-fragments or powders. These had already been analysed by Antonietta Gallone using the scientific instruments of the time, and can now be used for new research. This is the most valuable part of the archive, containing materials taken while restoring many works and artefacts from Italy’s historical and artistic heritage, with a particular emphasis on Renaissance pictorial art.

The “Physics Department Archive” section contains papers from Antonietta Gallone’s former office at the Department of Physics, and is yet to be reorganised. It consists of about twenty boxes of draft copies, manuscripts, photographs, negatives, letters, and preparatory material for publications. I started to index this section of the archive in terms of themes, with reference to the materials used in the diagnostic study of Leonardo’s Last Supper.

The Gallone Archive contains the largest collection of samples ever taken from Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. How did you organise it, and make it accessible to all?

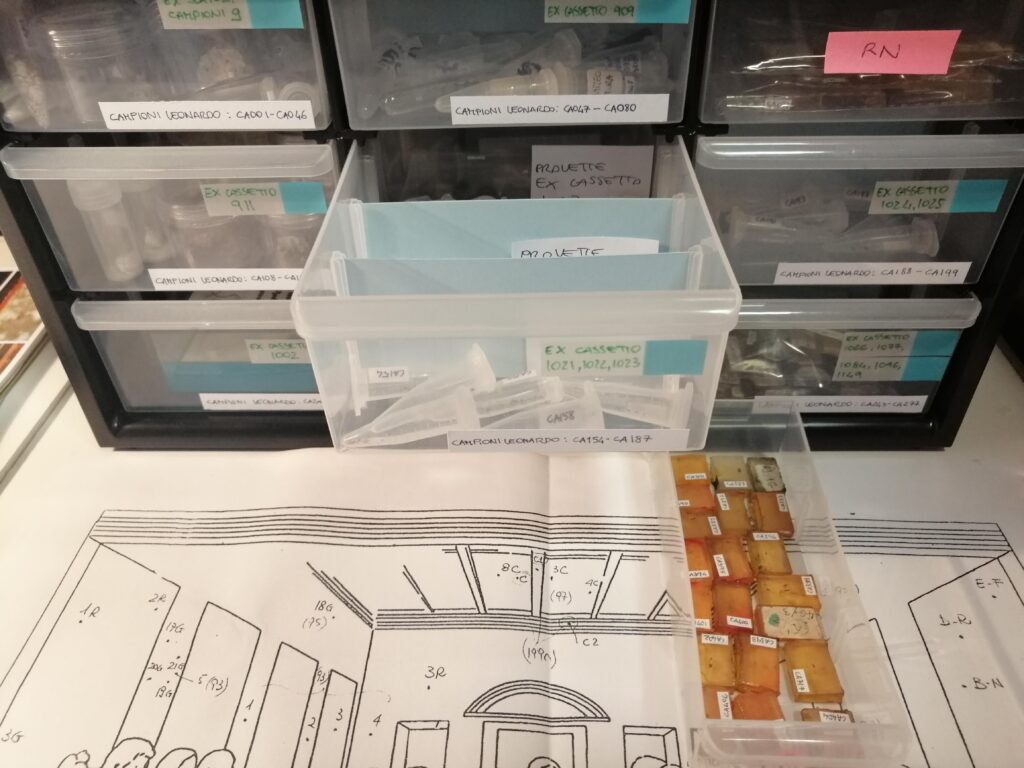

Well, this is certainly the largest collection, with over 400 samples taken from the Cenacolo!

Firstly, I had to look into the subject of archives consisting of samples from our cultural heritage, and the various problems associated with their conservation, reuse and distribution.

The first stage in the research project into the samples from the Last Supper was to catalogue and describe the materials taken from this work. I studied these under an optical microscope and indexed them in a conventional manner, using particular terminology. The samples had been stored over the years in glass and plastic tubes, sometimes without airtight stoppers, but also in paper sachets or recycled containers such as film canisters. So these were makeshift containers, fragile and quite unsuitable for the purposes of storing materials subject to deterioration.

So we transferred the samples to new, more suitable containers, following advice from Antonio Sansonetti at the Institute of Cultural Heritage Sciences.

As well as cataloguing and digitising the material, I was also able to carry out various analytical tests on the samples from the Last Supper, and demonstrate their potential for future studies. I worked in collaboration with the laboratories at the Politecnico di Milano: the ArtIS lab headed by Daniela Comelli, and the SoLINano lab of Gian Lorenzo Bussetti, and also with the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble and with the CNR-ISPC,

To return to the task of reorganisation: the ‘old-fashioned’ slides showing stratigraphic sections of the samples had to be digitised, and the paper and digital documents had to be correlated with the microscopic materials taken from the painting.

What was your final objective?

To locate, wherever possible, the exact points where the samples were taken from the painting, and make all the relevant data available on a digital platform. This would be primarily aimed at scholars, and particularly at those involved in conserving Leonardo’s work.

In fact, one of the outcomes of my research has been the creation of an Information System (IS) for the samples from the Last Supper. This has been produced in collaboration with the 3D Survey laboratory at the Politecnico, and the help of Cristiana Achille and Franco Spettu.

The IS allows you to access a database where the samples are all accurately referenced on the digital surface of the work, using the sort of GIS tools that are normally used in mapping. The system is currently being tested and finalised, and will be made accessible on a dedicated platform, designed both for experts in the field of conservation, and also for a wider audience.

To sum up: you start with a photograph of the Last Supper, which you can navigate like a high-resolution map in order to locate the various points of the samples and discover the results of the tests carried out on the relevant areas. You will also be able to consult reports and images, update the site with new data, and then monitor the file related to the conservation of the painting over time.

How important are new technologies to your work?

Extremely. The possibility of combining a historical and artistic approach with a scientific one allows us to make great strides in relation to our knowledge, protection, conservation, restoration, management and promotion of Italy’s historical and artistic heritage.

Analytical testing on works of art was generally limited during the twentieth century, but recent technological advances have allowed us to interpret the data much more accurately, and now we are also able to carry out non-invasive tests on works of art, i.e. tests that do no damage to the object under investigation.

So, to get back the Gallone Archive, the samples provide a valuable source of data for future research projects into cultural objects.

From the study of humanities at Milan University to the Politecnico. A real change…

A real change, yes. It wasn’t easy at first. It was a bit of a leap in the dark; I admit there were occasions when I thought I might have made the wrong choice. I had to question my whole approach to study and research. But this has allowed me to increase my range, not only in terms of knowledge, but also experience.

During this time, I’ve met professional experts, and especially, some very interesting people following pathways different from my own, but with whom I’ve had a fruitful exchange, leading to great personal and professional growth. This experience has opened my mind, and made me realise how limited my outlook and interests actually were.

I’ve had the opportunity to undertake the practical work of cataloguing, to use diagnostic techniques in relation to our historic and artistic heritage, to examine historical and documentary evidence in relation to artistic objects, but also to study the technical aspects.

Although the history of art is one of the widest branches of knowledge, it is often seen as a world apart, without any relation to other disciplines, especially those in the field of science. This is due to a centuries-old misunderstanding, which makes a clear distinction between scientific culture and humanistic culture. But Leonardo da Vinci himself worked towards the unity of the intellect. Indeed, he wrote in the Codex Arundel: “As every divided kingdom falls, so every mind divided between many studies confounds and saps itself.”

After the doctorate, the FAI. What are you involved in now?

For the last few months I’ve been working in the field of Cultural Affairs at the Italian Environmental Fund (FAI), a non-profit organisation that aims to protect and upgrade the country’s artistic and environmental heritage. It was founded in 1975 by another great woman in the story of Milan, Giulia Maria Crespi, together with Renato Bazzoni. Her autobiography, “Il Mio Filo Rosso”, is well worth reading.

I’m currently working in two different departments: Large Content Projects and Promotion. In the first department, I’m researching the sites open the public and selecting places suitable for holding FAI’s two well-known flagship events: the FAI spring and autumn days. In the second department, I’m helping to promote some of the assets owned by the Foundation, for example by creating detailed material for visitors.

What advice would you give to a young person wanting to follow your pathway?

Not to exclude the possibility of deviating from the route.

Studying for a doctorate, especially in an interdisciplinary context, provides an opportunity to expand your knowledge, and acquire new skills through a scientific approach to artistic matters. In this regard, the Politecnico is right at the forefront in the Italian educational scenario for its potential to produce the sort of expertise that can combine the scientific knowledge required to investigate works of art with the historical and artistic context of the materials, so acting as a bridge between the two worlds.

What goal would you like to see fulfilled?

I’d like to ensure that the objectives of the work I’ve carried out at the Politecnico, and the efforts of others before me who helped to conserve and organise the Gallone Archive, are promoted and valued by the University.

The Politecnico hosts other important archives of architects, designers and engineers: Brioschi, Bottoni, Chiodi, Grassi, Mucchi, Natta, Secchi and Steiner, to name but a few. These collections of documents are a vital reference point for those working in architecture, design, engineering or art history.

The Gallone archive is unique in this context, a rare example of somewhere other than Centre for Restoration that contains samples from a work of art, and so offers opportunities for research at a global level. My wish would be to see the Gallone Archive transformed into a proper facility for studies in the field of Heritage Science, a sort of physical library for the History of Restoration.