Building staircases, not walls

Making technology understandable is not an act of dumbing down. It is a cultural, political, and design choice. It means deciding who gets to participate in innovation and who is left out, who can experiment and who is forced to merely use opaque tools. Massimo Banzi, co-founder of Arduino, has been advancing this idea for more than twenty years, long before terms like open source, maker culture, or artificial intelligence became central to public debate.

When he speaks to an audience of PhD students in computer science at Politecnico di Milano, Banzi does not construct a heroic narrative, nor does he offer a recipe for success. Instead, he traces an irregular trajectory made of teaching, attempts, mistakes, and unlikely contexts. Arduino, he explains, was not born as a startup or an industrial project, but as a response to a very concrete problem: teaching electronics to non-engineers without losing them in the first few minutes.

It is at this point that one of the key ideas of his work emerges: the entry threshold. Every technology, Banzi argues, has a decisive initial moment. If at that stage the user encounters friction, gratuitous complexity, or hostile language, the experience ends there. Arduino was created precisely to avoid this, allowing anyone to connect a board, install software, and see something working within minutes.

Designing technology means building staircases, not walls.

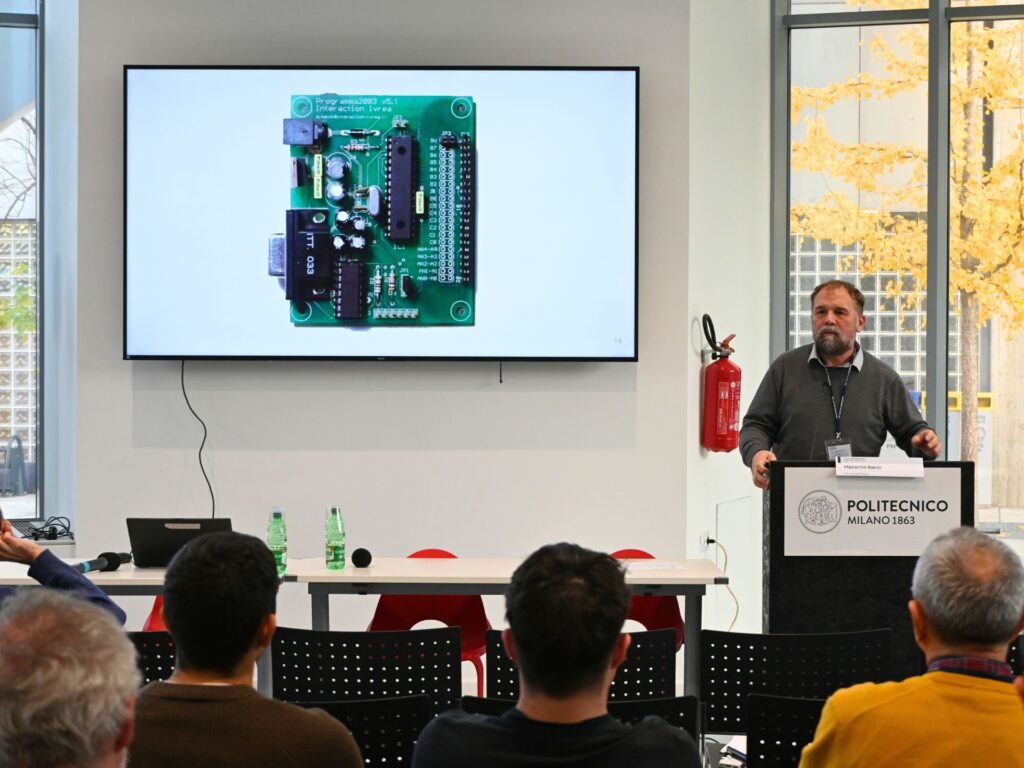

This focus on accessibility is not a technical compromise, but a deliberate design choice. Arduino was not conceived in an electronic engineering department, but in an Interaction Design school, within the cultural legacy of Olivetti. A context in which technology is never an end in itself, but part of a broader system that includes people, practices, and narratives. What matters is not the most powerful processor, but the clearest experience. Not the technical specification, but real use.

This approach resurfaces constantly when Banzi, in his interview with Frontiere, revisits the choices that shaped Arduino. Before open source, before the global community, there is a design philosophy that puts human beings at the center and treats simplicity not as a limitation, but as a responsibility.

The problem is not complexity

In his talk at the Politecnico, Massimo Banzi repeatedly returns to a misunderstanding that, in his view, still shapes how we think about technology: the idea that simplifying means giving up complexity. For Banzi, the opposite is true. Simplification is not a shortcut, but a conscious design act that requires time, iteration, and a deep understanding of what truly matters to the user.

“Sometimes the way we talk about technology is unnecessarily complicated,” he says. “Not because the technology is simple, but because we choose a language that excludes”. This insight stems from personal experience even before professional practice. As a child, Banzi recalls, he learned more by dismantling objects and playing with electronic kits than through abstract explanations. He did not know physics, but he understood phenomena, because someone had translated them into stories, images, metaphors.

Many years later, this intuition resurfaced when he began teaching electronics at an Interaction Design school in Ivrea. Students came from disciplines far removed from engineering: graphic design, cognitive psychology, communication. “The first time, I started by explaining what electrons are,” he recalls. “After ten minutes, I had lost the entire class.” The following day, he walked into the classroom with lemons, nails, and LEDs, and built an improvised battery. Attention immediately returned.

“With many people you can’t start from theory,” Banzi explains. “You have to let them enter the problem from another side. Experience comes first, then theory follows.” Non si tratta di una provocazione anti-accademica, ma di una riflessione su come le persone imparano e si apprendono a qualcosa di nuovo. Lo stesso vale per la tecnologia: se il punto d’ingresso è troppo ripido, la maggior parte delle persone si ferma.

Arduino was born precisely from this awareness. Not as a technological exercise in style, but as a tool for rapid prototyping without requiring expertise in electronics. “The initial moment is decisive,” Banzi says again in the interview. “If you lose someone in the first ten minutes, you’ve lost them forever.” This is why the goal is not maximum power, but minimum friction.

The project was stripped of everything that was not essential to the initial experience: complex configurations, jumpers, intermediate steps. “We wanted someone to plug in a cable, download some software, and start doing something within ten minutes,” Banzi recalls. That first result, often just a blinking LED, is not a trivial detail, but a psychological turning point that transforms frustration into curiosity.

Making technology understandable does not mean impoverishing it.

Banzi insists on this point because he considers it even more relevant today, in an era dominated by increasingly powerful and opaque tools, from artificial intelligence to complex systems. Technologies change, but the risk remains the same: building walls instead of staircases. “If someone looks at a tool and thinks ‘this is not for me,’ we’ve failed as designers”, he says. The challenge, then, is not to reduce complexity, but to distribute it over time, accompanying people step by step.

It is from this idea of design as responsibility that the choice of open source almost inevitably takes shape. Not as an ideological slogan, but as the necessary infrastructure to support a community that grows alongside the tools it uses.

Open source as social infrastructure

When Banzi begins to talk about open source, both in the talk and in the interview, his tone shifts slightly. Not ideological, but more decisive. It is as if he wants to clear the field of another persistent misunderstanding: the idea that open source is primarily a philanthropic gesture, a voluntary renunciation of economic value in the name of an abstract ethical principle. For Banzi, it was never that simple

“Open source comes from a combination of reasons,” he explains. “Of course there’s an ethical dimension, but there’s also very concrete convenience.” On one side, there are extremely powerful open source software tools, often developed by highly skilled communities, but difficult to use. Taken individually, they remain the domain of a few. Assembled into a coherent experience, they can become accessible to many. “If you build something around them, the user no longer has to touch those pieces of code. And that’s already enormous value.”

But the deeper motivation concerns community building. When Arduino took its first steps, Banzi and his collaborators literally started from zero. There was no user base, no brand, no structured company. In that context, convincing people to contribute was a matter of trust. “If I contribute to something,” Banzi observes, “I want to know that no one will take it away from me.” Open source thus becomes a guarantee: what is built remains a common good.

Open source works when people know that what they do will not be taken away.

This dynamic also emerges very clearly in the interview. If a project is too proprietary, people begin to ask a legitimate question: why should I help improve something from which only you will later benefit economically? Openness, in this sense, does not slow development, but accelerates it. It reduces friction, multiplies contributions, and transforms passive users into active participants.

Over time, this choice also proves surprisingly far-sighted from an industrial perspective. “Today open source has already won in many areas,” Banzi says. “If someone proposed proprietary software to build a complex web application, the answer would be: are you crazy?” This is not just provocation, but recognition of a deep cultural shift affecting both developers and companies.

Many large corporations, Banzi notes, have begun open-sourcing internally developed tools not out of generosity, but necessity. “When a large community forms around a tool, its value grows exponentially.” There is also another often underestimated factor: people want to work on open source projects. “Many companies opened up because their employees wanted to work on open source rather than completely closed systems.”

This does not mean, Banzi clarifies, that everything must be open. The idea of total, indiscriminate openness does not convince him. “It’s important that the part that really makes what you’re building work is open source,” he explains, “then on top you can add a layer of user experience that makes the product yours.” It is a pragmatic balance that separates shared infrastructure from application-specific differentiation.

In many sectors, open source is no longer an alternative. It’s the standard.

In Banzi’s account, open source never appears as an end in itself, but as a necessary condition for building durable ecosystems. A way to lower entry barriers, distribute decision-making power, and allow innovation to circulate. And it is precisely when this model meets industry, especially historically closed companies, that its potential becomes most evident.

This is where Arduino’s story intersects with that of Qualcomm, marking a symbolic turning point that Banzi reads as a victory not only for a project, but for an entire way of making technology.

From the maker ecosystem to industry

When Banzi talks about Arduino, he carefully avoids describing it as a single object or a product line. In his narrative, Arduino is a trajectory that crosses different worlds and connects them: education, research, the maker movement, industry. A platform that changes shape depending on context, while maintaining its core function: lowering the threshold of access to technology.

In his talk at the Politecnico, Banzi shows how this openness has generated over time a constellation of practices and communities. From fab labs created to offer shared spaces and tools, to Maker Faires that turn technological experimentation into public events, to research projects and scientific applications developed outside traditional industrial circuits. “Arduino was never the end goal,” he observes. “Value emerges when people with different skills manage to meet.”

It is in this intermediate space that some of the most significant projects take shape. Banzi often mentions Safecast, the initiative born after the Fukushima nuclear accident, when groups of citizens began building sensors to independently measure radiation levels. Official data was insufficient, trust in institutions fragile. Arduino became the means through which a distributed community built an alternative environmental monitoring infrastructure. “In that case,” Banzi recounts, “technology allowed people to negotiate the truth.”

These are not isolated episodes. Over time, Arduino has been used to create open source scientific instruments, microscopes, DNA analysis devices, environmental monitoring systems, and even low-cost medical equipment. Projects that in traditional contexts would require enormous investments and complex infrastructures. Here, instead, they emerge from the meeting of different skills, made compatible by a shared platform.

This same model, Banzi emphasizes, eventually attracts the attention of industry as well. Not industry simply looking for a product to integrate, but industry beginning to question its own approach to innovation. The agreement with Qualcomm, announced after years of collaboration, represents for Banzi a particularly significant signal. “Qualcomm has always been considered one of the most closed companies in the sector,” he says. “For years, they wouldn’t even give you processor documentation without signing a mountain of NDAs.”

With Arduino, something changes. For the first time, a Qualcomm processor becomes available in small quantities, technical documentation is made public, board schematics are accessible. “If you create too much friction, people choose another component,” Banzi observes. It is a simple but powerful insight: in an increasingly fluid market, openness becomes a competitive condition.

This step also marks a symbolic turning point. A historically closed company adopts practices of openness not out of idealism, but because it recognizes the value of the ecosystem Arduino helped build. Banzi reads this as a cultural victory before an industrial one. “In part,” he says, “Arduino helped change the attitude of semiconductor companies.”

If you create too much friction, people will pick another component.

The account is not triumphalist. Banzi is aware of the tensions that run through this model: competition with low-cost clones, the difficulty of remaining open source in an aggressive market, the need to form alliances to survive. But even here, the same logic applies: not defending a closed perimeter, but strengthening shared infrastructure.

And it is precisely this attention to infrastructure, rather than individual products, that prepares the ground for the final theme of both the talk and the interview: the relationship between research, responsibility, and the future.

Research, young people, responsibility

The final part of Banzi’s talk at Politecnico di Milano is the most direct. He stops recounting cases, projects, trajectories, and addresses the audience explicitly: PhD students, doctoral candidates, young researchers building their relationship with technology in a historical moment dense with both promises and ambiguities. The tone is not rhetorical encouragement, but shared responsibility.

Banzi starts from a simple observation: doing research and innovation today means operating in an ecosystem that rewards speed, visibility, performance. Startups, funding, metrics, hype. “You have to be very careful not to get confused by the mythology of the Californian startup,” he says. A myth that risks flattening everything into a single model of success, often far removed from the real problems technology could address.

This distortion, in his account, is particularly evident when comparing consumer applications with industrial technologies. “An industrial application is not less important than a consumer one,” he stresses. Often the opposite is true. Technologies that operate in production processes, healthcare, energy, or the environment have a concrete and lasting impact on people’s lives, even if they never make newspaper headlines.

This perspective also returns in the interview when Banzi reflects on the Italian context. Italy, he observes, is an extraordinary place to develop technology: high-level universities, widespread expertise, unique manufacturing capabilities. But it is also slow, resistant to change, reluctant to experiment. “In Italy we’ve always done it this way,” he says with a hint of irony, “and that’s exactly where you realize there’s room for innovation.”

His advice to young researchers is not to emulate external models or chase the latest technological trend. It is an invitation to question the impact of their work. “Use your skills to solve real problems,” he says. “If there is positive impact, the money will come. But starting only from the idea of making money is the best way to fail.”

From this perspective, Arduino’s story becomes less an example of entrepreneurial success and more a demonstration of method. It did not emerge from a neatly packaged vision or a detailed business plan. It grew from a concrete need, built step by step, sustained for years through parallel work, teaching, experimentation. “We didn’t have a mission, a vision, or investors,” Banzi recalls. “We started with 700 euros and the idea of doing something that made sense.”

This is also why Banzi insists on the value of the long term. Twenty years today is an anomaly in the technological landscape. And yet, it is precisely this duration that allows a project to become infrastructure, to sediment into practices, to generate impacts that go beyond the initial product. Arduino, in its current form, is the result of continuous layering, not a single stroke of genius.

If you manage to build small successes one on top of another, you can get anywhere.

The conclusion of the talk returns to the image that has run through it from the beginning. Every time someone encounters a new technology, Banzi says, they implicitly ask whether they will have to climb a wall or walk up a staircase. If access looks like a smooth, vertical surface, the response is almost always refusal. If, instead, the technology offers clear, progressive, accessible steps, learning becomes possible.

It is in this seemingly small but deeply political choice that the future of innovation is decided. Building staircases means accepting that the value of a technology lies not only in what it does, but in how many people it manages to bring along with it.