Academic revolutions sometimes arise in silence, between a university lecture hall and a Faculty meeting. In the 1970s, an idea took shape at the Politecnico di Milano that was destined to profoundly change Italian engineering: combining technical expertise with an economic-organisational vision. This intuition led to Management Engineering, a programme of study that is now well established but was entirely new at the time.

We talk about it here with Armando Brandolese, one of the architects of that pioneering period, who contributed to founding the Bachelor of Science programme and later the MIP, the management school at the Politecnico.

Professor, how did the idea of a new type of engineering — ‘management’ engineering — come about?

It all started at the end of the 1960s, when a few young professors at the Politecnico (including Professor Wegner, Professor Roversi and myself) began to look at topics that went beyond traditional mechanics. We were working at the Institute of Mechanics under the director, Antongiulio Dornig, our point of reference, and collaborating with Professor Raimondi, then a professor of Mechanical Systems and a consultant for Techint.

With him, we began to study problems related to industrial plant management: the production of different product ranges in a single plant, downtime and setup costs, maintenance, logistics, and choice of production chain. In short, we realised that the job of an engineer had to include both a management vision and a technical view.

At the same time, another group consisting of Professors Brioschi, De Maio and Bertelè had formed in the Department of Electronics to address economic and organisational issues. At first we continued on our separate ways, but our paths soon crossed: the two founding cores of Management Engineering were born.

What was the economic and industrial situation at the time?

Italy was experiencing a period of great industrial development. Mechanical and manufacturing companies were growing rapidly and facing complex production problems: product ranges, batch management, maintenance, quality.

At the time, the Japanese model of Total Quality Management was starting to stand out, and I visited Toyota with some colleagues to learn about their approach first hand.

There was an awareness that engineers could no longer just design machines. They also had to know how to manage them, optimise production and understand the underlying economic logic. It was a profound cultural change.

When did you shift from an idea to the creation of a Bachelor of Science programme?

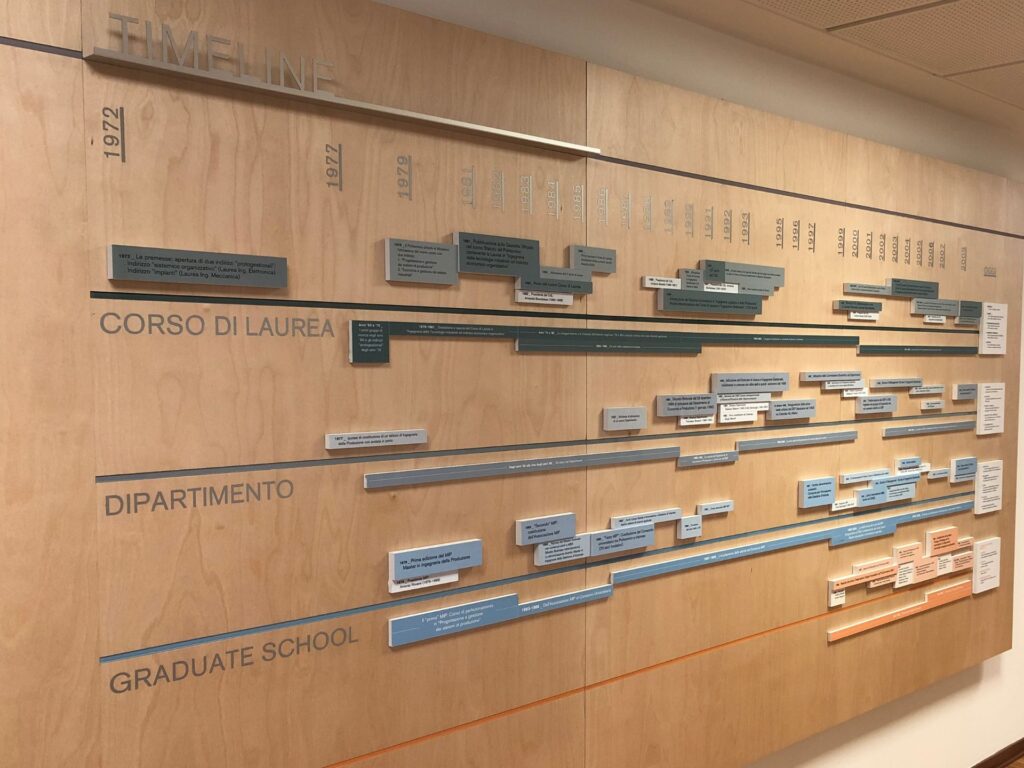

The proposal was developed in 1973 and 1974. We had already introduced a few innovative courses — maintenance management, production management, quality, logistics — within the Mechanical Engineering programme. But we realised that we needed a consistent path, an independent Bachelor of Science programme.

An unexpected event accelerated everything: the 1976 earthquake in Friuli. In order to rebuild the university system in the area, the Ministry had established a new course in Udine for ‘industrial technology engineering on an economic-organisational track’. It was a decisive precedent. With the support of Dean Massa, we managed to introduce the same course at the Politecnico di Milano.

Was there resistance at the university or initial scepticism towards the introduction of a ‘hybrid’ Bachelor of Science based on both engineering and economics?

Yes, initially there was a lot of scepticism. Some colleagues felt that the subjects — quality management, maintenance management, production — were not ‘real’ engineering topics. Out of prudence, the Faculty council set a limit of 50 students.

That first year, however, we already received many more applications. After two or three years, there were hundreds of candidates. I suggested abolishing the limit, and the Faculty approved. That year we had over 900 first year students. This unexpected boom confirmed the need for training in this new field.

What was the original idea of a management engineer?

We wanted to train a figure who could integrate technical and management skills, an engineer who could speak the language of both production and business organisation. At the time there was a skills gap. Companies needed professionals who were familiar not only with equipment and technology, but also with planning, logistics, quality and economic management.

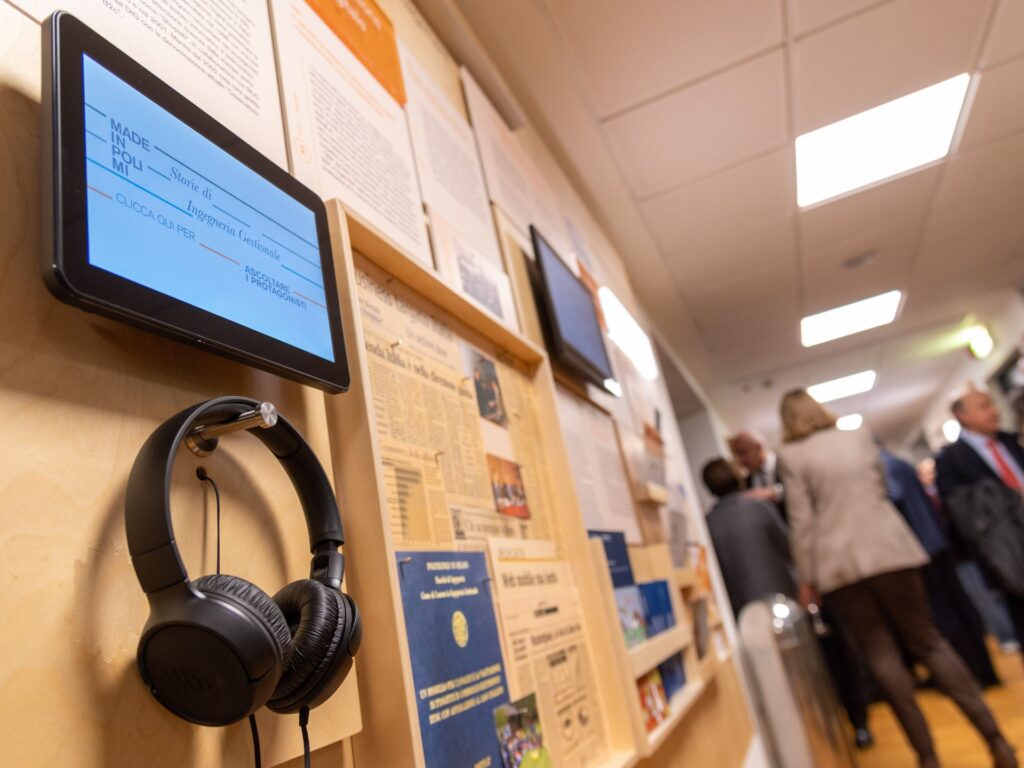

The MIP, the School of Management at the Politecnico, also grew out of that experience, right?

That’s right. The idea developed in the early 1970s, when I was also teaching at SDA Bocconi. One day my colleague Professor Roversi asked me: ‘Why don’t we create a master’s degree at the Politecnico?’ So we founded the MIP – Master in Production Engineering.

It started out almost like a bet, with about 20 members, in a few classrooms at the Politecnico and then at the Palazzo delle Stelline. It was the first step in what would become a large school of management, combining technical rigour with a managerial approach.

What subjects were taught in the first years of the Bachelor of Science programme?

In the first two and a half years, students followed the basic engineering courses — mathematics, physics and construction science. Then in the fourth year came more characteristic topics: production management, maintenance, quality, economics and business organisation.

It was a balance between technical basics and openness to the business world. And I would say that this approach has remained over time.

Looking back on that journey today, what are you most proud of?

The people. We managed to train and involve outstanding young people who went on to become professors, researchers and managers. I am thinking in particular of Andrea Sianesi, who worked with me a long time, or Giovanni Azzone, who became Rector of the Politecnico. And also Alessandro Perego, Marco Perona, Sergio Cavalieri and even others.

Many of them have helped the School to grow and give it an international reach. This, more than anything else, is what I am proud of.

Today, Management Engineering is one of the most popular Bachelor of Science programmes. Would you have imagined it back then?

Maybe not in today’s proportions. But it was clear from the outset that it met a real need: combining technical culture with the ability to manage complex systems.

After all, this is the hallmark of a management engineer: understanding how things work while driving change.