Every seven minutes, a woman dies somewhere in the world as a result of postpartum haemorrhage: a serious complication that occurs immediately after childbirth. According to the World Health Organisation, there are about 70,000 victims every year, and most of these deaths occur in low-income countries, which lack sufficient health facilities, medicines and trained personnel.

This emergency gave rise to an idea: to create a safe, accessible and easy-to-use device to counteract postpartum bleeding. Its name is BAMBI, and we’re now going to tell you about it through the voices of those who conceived and developed it: Maria Laura Costantino, scientific coordinator of the BAMBI project and professor in the Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering, together with Francesco De Gaetano, a researcher in his group, and Serena Graziosi, professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

How did the idea for the BAMBI project come about? Where did it all start?

Francesco De Gaetano:

The idea stemmed from a meeting and a practical question posed by Dr. Alberto Zanini, gynaecologist and former head of the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Operating Unit at the “Sacra Famiglia” Hospital in Erba, who turned to the Technology Transfer Office (TTO) of the Politecnico di Milano with an important question: how can we save those women in developing countries who die from postpartum haemorrhages, often due to a lack of suitable equipment?Dr. Zanini had a particular idea but needed expert help to turn it into a real device. And so what was initially only a project in the mind of a doctor came to involve our group of researchers; I began to work on it during my post-doc, together with other members of Prof. Maria Laura Costantino’s team. To enable an all-round approach towards developing the device, Prof. Serena Graziosi’s group was also called in, thus extending the skills we had available.

A multidisciplinary team was established straight away. But how did you get the resources to develop the project?

Francesco De Gaetano:

As a result of this multidisciplinary collaboration, we were able to take part in various contests and award schemes. The first was the 2019 edition of Switch2Product, the entrepreneurial empowerment programme designed to nurture research projects at the Politecnico di Milano, enabling access to cash grants, business training, incubation and access to a network of corporations and investors to help bring the project to market. The grant we were awarded gave us the resources to purchase materials and support the researchers. The aim was clear: the device would have a huge social impact, even though it would not generate large financial returns like those produced by other innovations. In critical settings, where a condom tied with a string was often used, conditions were extremely difficult, and this device could make a big difference.

A decisive moment was our participation in the contest for the POLISOCIAL award, an initiative by the Politecnico di Milano to support scientific research with a high social impact, thanks to funds raised by the 5 per thousand tax measure. Although the post-Covid edition was very pandemic-oriented, the BAMBI project was actually a perfect fit, as supporting deliveries in rural areas and reducing unnecessary hospitalisation was seen as a crucial objective.

Maria Laura Costantino:

With these important contributions, the team became a solid entity, with representatives from chemistry, mechanics, design and the technology transfer office (TTO) all working together. This allowed us to develop the product design, to conduct all the necessary tests to assess the robustness of the prototype, and to carry out usability tests.

With the help of Dr. Zanini, we involved several experienced doctors, comparing our prototype with the device currently considered the gold standard, which costs between $350 and $500. Despite the availability of this expensive device, most doctors chose our prototype for its ease of use, confirming the potential social impact of our innovation.

Have usability tests been carried out on the device? How were they conducted and who supported you during these trials?

Francesco De Gaetano:

To really understand if the BAMBI device worked, the team needed to test it in the field… but in a safe way. We organised two types of tests, one of which involved trained personnel, such as doctors and midwives who are used to assisting births, while the other was comprised of people with no medical training, and since there is often no doctor available in rural villages the device also needs to be able to be used by them.

The tests with non-experts were carried out inside the Politecnico di Milano, in labs that were equipped to observe how the device was handled and how intuitive it was to use. While for the tests involving doctors and midwives, the team went straight into the wards in various hospitals. So, without interfering with the daily work of professional staff, we were able to compare BAMBI with the devices already in use, and to see whether it could really represent an effective, safe and simple alternative.

These usability tests were not just a technical exercise, but were also the first practical steps towards ensuring that every mother could have a safer birth, even in very isolated settings.

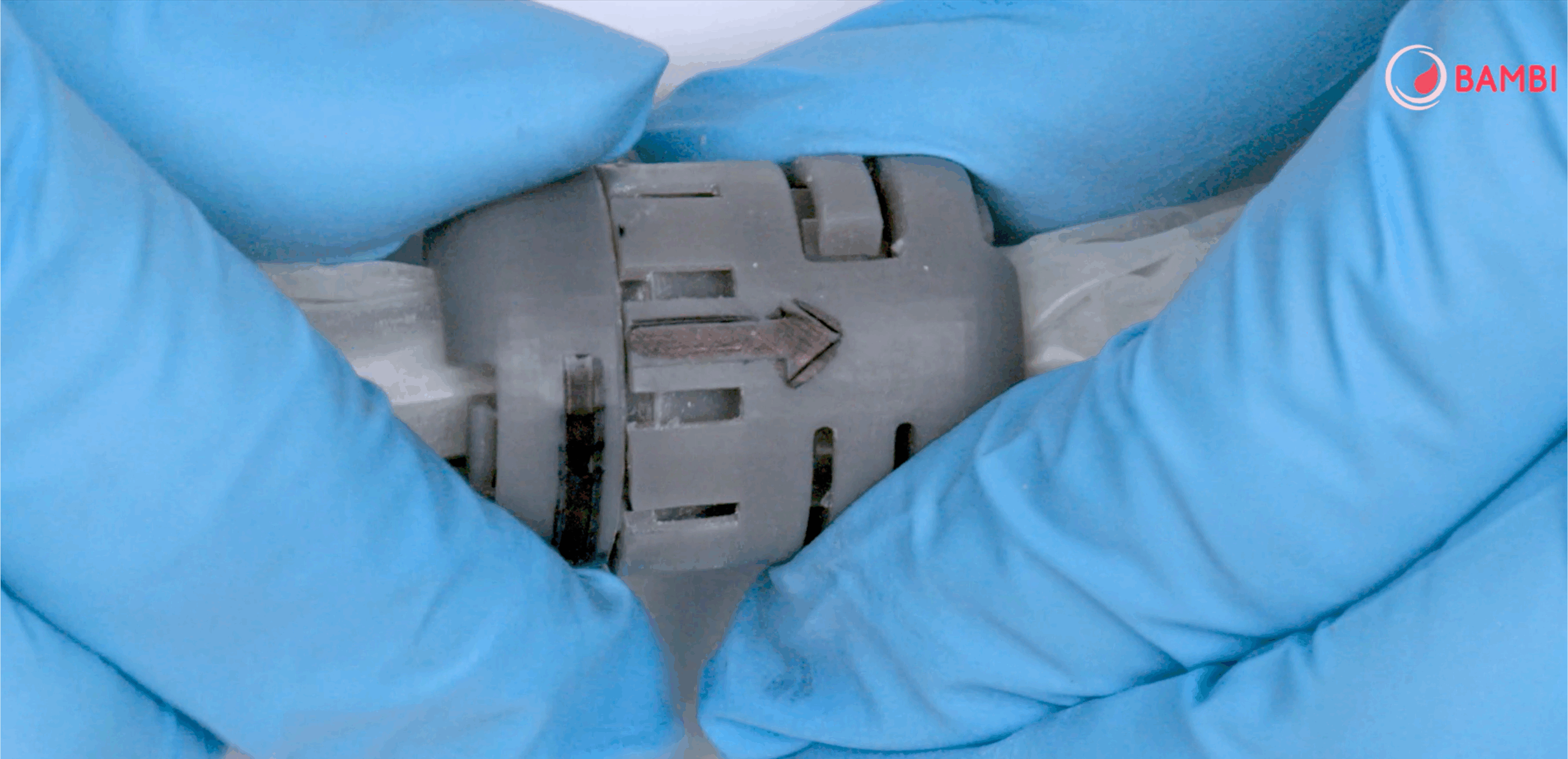

I read that one of the crucial components of the device – the connector – plays a central role in production of the kit. How was it developed, and what are the innovative features of this component?

Serena Graziosi:

The connector and the whole kit were developed as a joint project, involving collaboration between various teams of experts. Our colleagues from the Department of Chemistry played a key role, thanks to their experience in developing medical devices, while we at the Department of Mechanical Engineering focused on the design and refinement of the component.

We took a multidisciplinary approach right from the start: we decided jointly on the requirements for the device, taking into account its functionality, the dimensions needed for its use on the human body, and the suggestions provided by doctors in the field. We had to achieve a balance between practical needs, safety and usability.

Starting from the initial ideas developed by our colleagues in the chemistry department, we then moved on to digital models and prototypes created with 3D printing, a quick way to provide some working components to test. The main aim was to make the device intuitive and easy to use, both for experienced operators and for non-medical personnel.

The tests involved mechanical tests to ensure the connector was tight-fitting and reliable, and special simulations of a uterus, produced from materials that mimicked its real consistency, and with support from a gynaecologist. In this way, we were able to check the effectiveness and practicality of the device, ensuring that the balloon was always properly connected, without any loss of fluid.

The patented connector represents a combination of mechanics, chemistry and clinical needs, uniting innovation with ease of use.

Does the patent relate to the connector of the device?

Francesco De Gaetano:

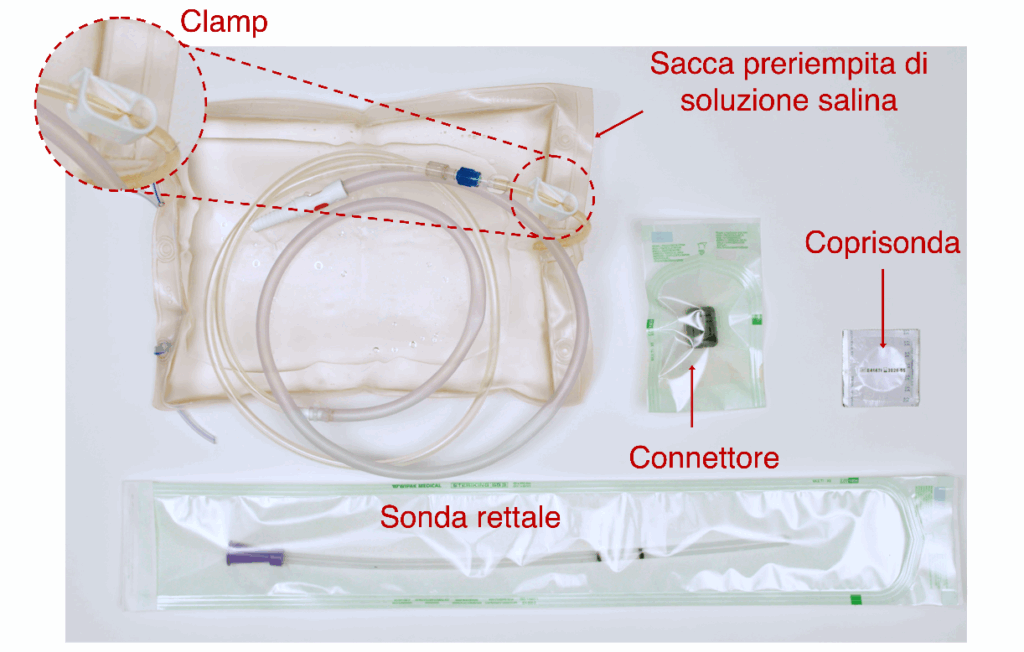

Yes, that’s right, the patent is just for the connector. There’s already a device used as a tamponade for intrauterine bleeding, so it wasn’t possible to patent a second device with the same purpose. The aim of our project was not to create a completely new device, but to make it accessible and offer it at a drastically lower price than a similar device already in existence.

The only patented element was therefore the connector, which plays a fundamental role in the operation of the whole system: without it, the device wouldn’t work. It’s a simple-to-use component, but essential for ensuring the ease and effectiveness of the BAMBI kit.

As Professor Graziosi also explained, the device can be supplied either in separate parts, which can be assembled on site, or pre-assembled. This is precisely why the patented connector is such an essential part: it is easy to use and handle, and this means that anyone can assemble the device correctly, even if they have no experience.

This small component is crucial, because it holds the whole system together and ensures that the device works effectively.

Was it hard to come up with the design for this connector? How long was the process, and how did you feel when you succeeded?

Francesco De Gaetano:

We were very satisfied and pleased with the result. Of course, in our work we never stop: even when we achieve a goal, there’s always the desire to do better.

The connector passed all the tests that we’d set ourselves, because there were no clear regulations that indicated how to carry out tests.

We focused on the worst possible conditions in which the device could be used and made sure it was both durable and functional.

However, at first we only had a 3D-printed prototype, which was difficult and too expensive to produce on a large scale.

We were helped here by the Politecnico’s latest “Proof Of Concept” grant provided through the NRRP for patents with a low TRL (technology readiness level). With this funding of about €40,000, we were able to make the technological advance needed to produce small batches with injection moulding.

We now have moulds that can produce up to 10,000 pieces, much faster and at much lower cost. In the coming days, we’ll be completing the technical and scientific report on this funding, and will then focus on publishing the results.

So did you also acquire any medical skills during this project? In other words, although you were not biomedical experts, did you have to deal with certain clinical and obstetric aspects?

Serena Graziosi:

As a mechanical engineer, I was the greatest “outsider” in the medical setting. On the other hand, my colleagues in the team already had experience in the biomedical field as a result of their research and teaching work. For me it was a time of significant growth; before this I was unaware of the magnitude of the problem of postpartum haemorrhage in developing countries. Working on this project allowed me to look into subjects I knew nothing about before, and to realise how real and how urgent the problem is.

Francesco De Gaetano:

Even for us who specialise in the field of bioengineering, the issue had never been addressed; our work is usually concerned with the heart, lungs, kidneys, pancreas and other major organs, but never with the uterus or postpartum complications. Dr. Zanini’s role was fundamental; without him we would probably never have focused on this problem, and many women in high-risk settings would continue to have no effective alternatives.

This project has allowed us to explore a new area of research and to make a practical contribution towards reducing postpartum mortality.

Maria Laura Costantino:

I would like to add that from an educational standpoint, the experience has had significant value. We have been able to share the data we collected with the scientific community, for example at the School of Bioengineering at the Politecnico di Milano, and to talk about “frugal engineering” as applied to medical devices for developing countries. The experience of working with Dr. Zanini was not just scientific, but also educational and socially important.

What stage are you at now in distributing the device?

Francesco De Gaetano:

Before we get to the actual distribution, there’s a crucial stage for any medical device: the clinical trials. So far, the device has only been characterised and tested in the lab, but in order to be able to market it and obtain the necessary licences from the regulatory authorities — which vary from country to country — it is vital to test it in the field.

We are therefore moving in this direction, and looking to work with charities such as CUAMM, Emergency and other organisations active on the ground. It’s very important that the trials are conducted in settings where the device is really needed; it would make no sense to test it in Northern Italy, where there are already well-established alternatives. In countries where the alternative is often a piece of string, the trial is not only useful from a scientific standpoint, but also from an ethical perspective.

Do you think that in the future this device could replace those already in use in hospitals?

Francesco De Gaetano:

We don’t think that’s possible. Of course, the cost savings would be significant, but that was not the main aim in developing this device. It has been designed for use in developing countries, not for nations that are already industrialised.

It was also not designed for home use in developed countries, something that occasionally appears in newspapers; such a use is now discouraged and is problematic for various reasons.

Maria Laura Costantino:

We’d like to point out that the device has been developed specifically for use in contexts where postpartum mortality is high and where there’s a lack of medical personnel. In such situations, including local hospitals and rural settings, it may be easier to train people such as local nurses, often local women who provide assistance during childbirth, rather than relying solely on doctors.

So you’re thinking of distributing the device mainly through associations?

Francesco De Gaetano:

That’s right, the distribution network will initially be based on associations that operate in developing countries. Then, as Dr. Zanini explained to us, if the device is found to work well and the cost remains sustainable, there is nothing to prevent us trying to obtain licences in industrialised countries, such as Europe and America, at some point in the future.

In many modern hospitals now, the most comparable device – the Bakri Balloon – is not always available. Fortunately, with proper drug management and by maintaining the cold chain, postpartum haemorrhage can be controlled in most cases.

On the other hand, our device would cost just a few Euros in developing countries, and would ensure that every local hospital always had a proper instrument available. However, as Professor Costantino also pointed out, the main aim now is to focus on introducing the device into the areas of maximum risk.

When is BAMBI used to stop bleeding as an alternative to medication?

Francesco De Gaetano:

The balloon is not a substitute for drugs, but is used when they are not sufficient. Typically, a drug such as oxytocin would be administered first; it stimulates contractions of the uterus and helps to stop bleeding. However, if the bleeding continues, it means that there is a more serious problem, such as a vascular lesion, and in that case the drug would not be sufficient.

The balloon is actually a mechanical device that works in a physical way; it is inserted into the uterus and inflated to exert internal pressure which then stops the bleeding. It’s like inserting a “cloth” to plug the haemorrhage. So it’s not an alternative to drugs, but a second line of defence, to be used when drugs don’t work or are not available.

Serena Graziosi:

I would like to add that the BAMBI kit has been specifically designed for use in places where drugs are often unavailable or can’t be properly stored, such as field hospitals or rural areas. The idea is to use simple materials that are already found in these places to create an effective device, even during emergency situations.

Maria Laura Costantino:

That’s right. Unfortunately, field hospitals are still a daily reality in many parts of the world. BAMBI was designed for use in these settings: places where conditions are difficult, but life goes on, children are born and women need be able to give birth safely. The device is designed to fit the logistic situation in these places, using components that are already available, and offering practical support where it is most needed.

Have you already got partner companies working with you to produce the connector?

Serena Graziosi:

Yes, thanks to the PoC funding we were able to find a company that has actively helped us develop the mould. This company not only followed our instructions, but took part in designing and building the mould, helping us revise the structure of the connector, which was originally designed for 3D printing.

They looked at the production constraints, the viability and the structure, refining the design for injection moulding, while minimising the production costs for both the mould and the connector. In their work with us they showed great care and sensitivity towards the project, becoming almost part of the team rather than just an external supplier.

Francesco De Gaetano:

That’s right. Their support was crucial: they responded very quickly, even working at weekends to produce functional prototypes. They became more than an external supplier, behaving like a true partner in the development process.

Does your work end here, or will you monitor its progress to ensure the device is actually adopted in the target countries?

Francesco De Gaetano:

No, this is not a page-turning exercise, we’ll be supervising the whole process very carefully. We don’t have economic or commercial interests, we’re concerned with the real impact that this device can have on the health of vulnerable people. We want to make sure it’s used correctly and reaches those who need it most.

After we’ve found a company that will take on large-scale production, whether they make the complete kit or just the connector, we’ll then need a specialist company to market the product.

I read that you have renounced the royalties on the patent… tell me more about that

Francesco De Gaetano:

By forgoing any royalties, we aim to make BAMBI accessible to anyone who needs it, without financial barriers. Our aim is to keep the project as simple and transparent as possible, with a clear focus on social impact and sustainability.

Maria Laura Costantino: By doing this, we can keep greater control over the progress of the device and ensure it remains an instrument designed to help communities, without the risk of it being turned into a commercial product driven by profit motives. Our aim is for BAMBI to remain accessible and useful, especially in settings where it can really make a difference.

Finally, I’d like to ask you for your personal reflections: what did taking part in the BAMBI project mean to you? Was it a particularly rewarding or difficult time? What message would you like to give to future researchers?

Francesco De Gaetano:

It was a very intense time for me, also at a personal level. My partner was pregnant during Covid, and while I was working on the BAMBI project, I often thought that we were lucky we could count on a hospital like the Mangiagalli, with all the proper safeguards. But elsewhere, in much more precarious places, a birth can turn into a tragedy in just a few hours.

This awareness gave me a strong sense of responsibility. When we were applying for funding awards, I felt that getting those really meant being able to do something useful.

I still remember my feelings when we won the Polisocial Award: it was a moment of intense and almost liberating joy. And we’ll never stop thanking the Politecnico di Milano for believing in projects with such a huge social impact.

BAMBI is not just a research project, it’s a practical way to save lives.

Serena Graziosi:

What I will always carry with me is the power of multidisciplinary work. This project involved different skills, in engineering, medicine and design, and allowed us to examine the problem from every angle. It was a complex task, but also effective for this very reason.

When you’re developing a product like BAMBI, you have to consider everything: the mechanical operation, the costs, the usability. And doing this together, with an enthusiastic and motivated team, really makes all the difference.

My wish for young researchers is that they find a topic they are deeply passionate about, and then work as a team: that is how the best solutions arise.

Maria Laura Costantino:

I completely agree with what has been said. Personally speaking, I’ve always believed that research should never be an end in itself. It shouldn’t be designed to show how clever the researcher is, nor about boosting their ego. Research must have a practical purpose: to create ideas, solutions, or devices that can improve people’s lives. In our case, we are biomedical engineers.

I actually started out as a mechanical engineer, at a time when there was no degree course in biomedical engineering. But I’ve always worked in the biomedical field, contributing to the growth of this sector. And precisely because of this, I feel a great responsibility to create solutions that are really useful, designed for the people who will use them, even – and most especially – in precarious situations.

A device should not just be designed for those who have resources and knowledge, but also for those who live in difficult conditions. BAMBI embodies this idea perfectly: it is designed to be simple, accessible and effective. And this was clear from the beginning of the project.

In recent years, I’ve also had the good fortune to work with the medical students in the MEDTEC School programme, the result of a collaboration between the Politecnico di Milano and Humanitas University. Many of them do summer internships in developing countries, in health facilities that are very different from those that we’re used to. Their experiences have confirmed how urgent it is to have devices like BAMBI, which can be used anywhere and by anyone.