MISCELAB was established in the heart of the Department of Energy, at the Politecnico di Milano. It is an innovative lab committed to the experimental characterisation of unconventional fluids for energy-related applications. The outcome of the synergistic connection between GECOS (Group of Energy COnversion Systems) and RELaB (REnewable heating and cooling Lab), MISCELAB marks a new frontier in thermodynamic research. The aim is to improve the efficiency of energy systems and reduce their environmental impact.

In this interview, researchers Antonio Giuffrida, Dario Alfani and Tommaso Toppi talk about the creation of the lab, the scientific and technological challenges faced, the potential of cutting-edge devices, and future prospects. This journey through numerical modelling, experimentation, sustainability and passion for research shows how innovation can arise from collaboration and scientific curiosity.

What is MISCELAB, how was it conceived, and what are its goals?

Antonio Giuffrida:

The lab is the result of a synergistic connection between the GECOS group, which deals with energy conversion systems, and RELaB (REnewable heating and cooling Lab), represented here by our colleague Tommaso Toppi. We both grasped the opportunity offered by the NRRP, particularly by the NextGenerationEU programme, which funds strategic research projects for the future of the country.

We are involved in the NEST (Network for Energy Sustainable Transition) project, one of the 14 major extended partnership projects selected by the Ministry of Universities and Research (MUR) under the NRRP. NEST aims to strengthen national research pipelines, and to promote participation in both European and global strategic value chains. It adopts a Hub & Spoke model, which coordinates research activities in nine key areas of sustainable energy transition.

In our case, the GECOS group operates in Spoke 5 focused on energy conversion, while RELaB participates in Spoke 8, dealing with optimisation, sustainability and resilience in the energy supply chain.

Dario Alfani:

Yes, Spoke 5 focuses on developing innovative materials, components and devices to improve the efficiency and flexibility of energy conversion systems. It also includes the study of advanced thermodynamic cycles, the use of synthetic fuels and hydrogen, and the application of artificial intelligence to energy processes. It’s the theme Antonio and I work on.

Tommaso Toppi:

Spoke 8, instead, deals with end-use electrification, energy efficiency and demand reduction. It aims to develop innovative governance and market models, high-efficiency technologies and materials, and digital tools for optimised energy management. It is a very broad scope, which also includes sustainability and resilience in the energy supply chain.

Antonio Giuffrida:

We have combined our research interests to better capitalise on the available resources. The collaboration between our two research groups has enabled us to design and operate a fully equipped lab by making the most of common skills and needs. We are currently in the initial phase of developing lab activities. The facility was only recently inaugurated.

Was the research team formed recently, or have you been cooperating for some time?

Antonio Giuffrida:

Actually, there were already research affinities between our groups. Participation in the NEST project offered us the opportunity to join forces and optimise the use of the available budget. This has allowed us to create a fully equipped lab for the experimental characterisation of innovative fluids. These are at the heart of both our historical research activities and the most recent ones related to the NEST project. MISCELAB deals with this by studying the thermodynamic properties of unconventional fluids. We do it for power generation applications, while RELab does it for reverse cycle applications, such as heat pumps. The best known thermodynamic cycle, the Rankine cycle, is based on water vapour. We, instead, analyse the performance of thermodynamic cycles operated with “alternative” fluids. Our aim is to improve their energy efficiency and reduce their environmental impact.

Tommaso Toppi:

Yes, I confirm that. Antonio has summed up our story very well. When we decided to participate in the NRRP, we saw the opportunity to also include, in the project, the purchase of devices for which funds are usually hard to find. Our group, RELab, has always considered certain tools a bit of a mirage, much desired as they are useful, but out of reach. We are talking about very expensive instruments. Together, our two groups have invested about 700 thousand euro of NRRP funds, as well as personal resources, to complete lab furnishings. By collaborating, we were able to purchase more instruments than each group could have done alone. It was an important step as research groups rarely cooperate on such terms. We can now say that we have a lab with remarkable potential. This aligns us with leading groups in Europe in this field of research.

Do you rank well, compared to other similar labs in Europe? What is your strength?

Tommaso Toppi:

Definitely. We are very well equipped in terms of devices. We have advanced and complete instruments that allow us to perform experimental measurements on the thermodynamic properties of pure fluids and mixtures.

Traditionally, fluids used in thermodynamic cycles, both for power generation and for applications such as heat pumps, meet historical needs. But today the market requires new applications, greater efficiency, and penetration into sectors that are still scarcely explored. This leads us to study alternative fluids, which are often not experimentally characterised as yet.

Most of the studies are based on theoretical models and established databases. However, these are derived from incomplete and often extrapolated experimental measurements. Having the ability to directly measure the properties we need, or to explore conditions or mixtures never studied before, is a huge advantage. This allows us to conduct innovative studies, and to be competitive at European level.

What are MISCELAB’s short and long-term strategic goals?

Tommaso Toppi:

The short-term goal is to bring the lab up to speed. Though we have carried out the activities envisaged by the NEST project, lab organisation has just been completed, and we are defining the procedures for its management. We also need to strengthen training in the use of devices for those performing tests.

Antonio Giuffrida:

Yes, the intention is to start the experimental characterisation of certain fluids that, to date, have been studied only through numerical modelling, based on literature data. Having experimental data will allow us to validate and refine the models, increasing the quality and reliability of our research.

The long-term goal is to participate in competitive calls, both Italian and international, and to consolidate the lab as a landmark for research on innovative fluids.

In this sense, MISCELAB is a concrete example of the NEST network’s strength. The Politecnico di Milano is one of the affiliates with cross-party participation in several thematic Spokes. The creation of the lab is the result of the NEST Foundation’s commitment to place researchers in the ideal conditions to carry out cutting-edge research by equipping them with infrastructure, instruments and a strategic vision.

Dario Alfani:

Another key goal is to collaborate with industry. Some of our instruments, such as the VLE system and the gas chromatograph, are extremely rare. Few laboratories in Europe have them. Unlike the calorimeter and density meter, which are more standard instruments, the VLE and the gas chromatograph have been custom-developed to meet the specific needs of our lab.

MISCELAB has also been designed to welcome external collaborations with companies and startups in the sector, and to support energy innovation even outside the academic context. Its contribution will be central in promoting technologically advanced energy transition, based on multidisciplinary collaboration.

Will MISCELAB become a key hub in the NEST network?

Antonio Giuffrida:

Yes, it will. With MISCELAB, the NEST network takes a further step towards a concrete, sustainable and research-based quality energy transition. It is an investment in skills, collaboration and innovation that looks straight towards the energy of the future.

Let’s talk about the equipment: what are its special features, and what allows you to do more than other labs?

Dario Alfani:

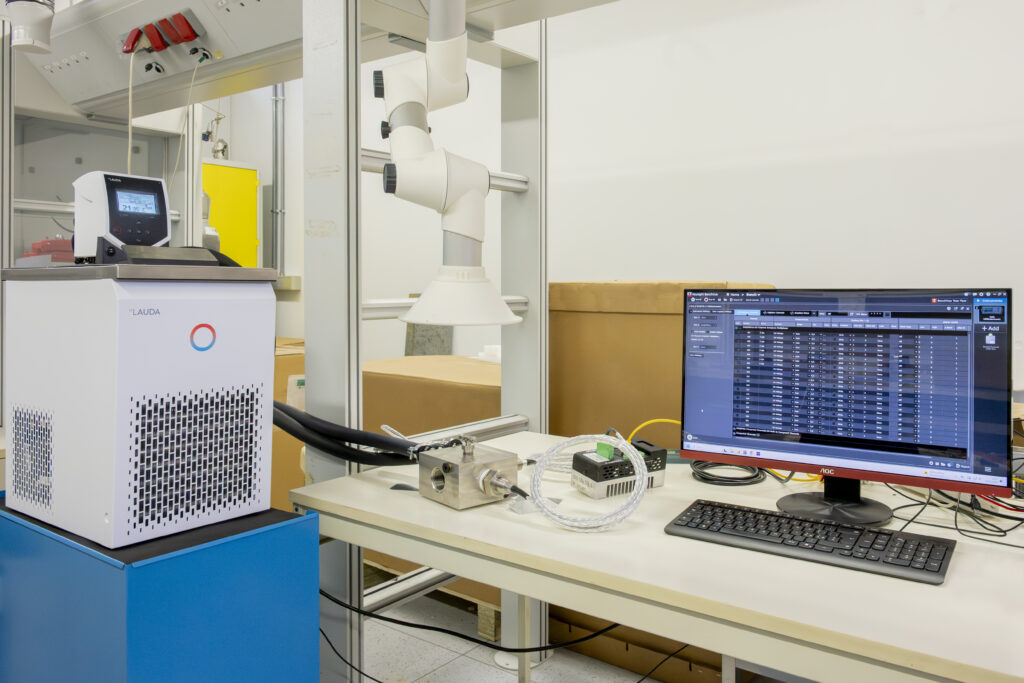

There are four main devices at the heart of MISCELAB. Each of them has a specific role in the characterisation of working fluids, particularly unconventional mixtures. Our research focuses on these.

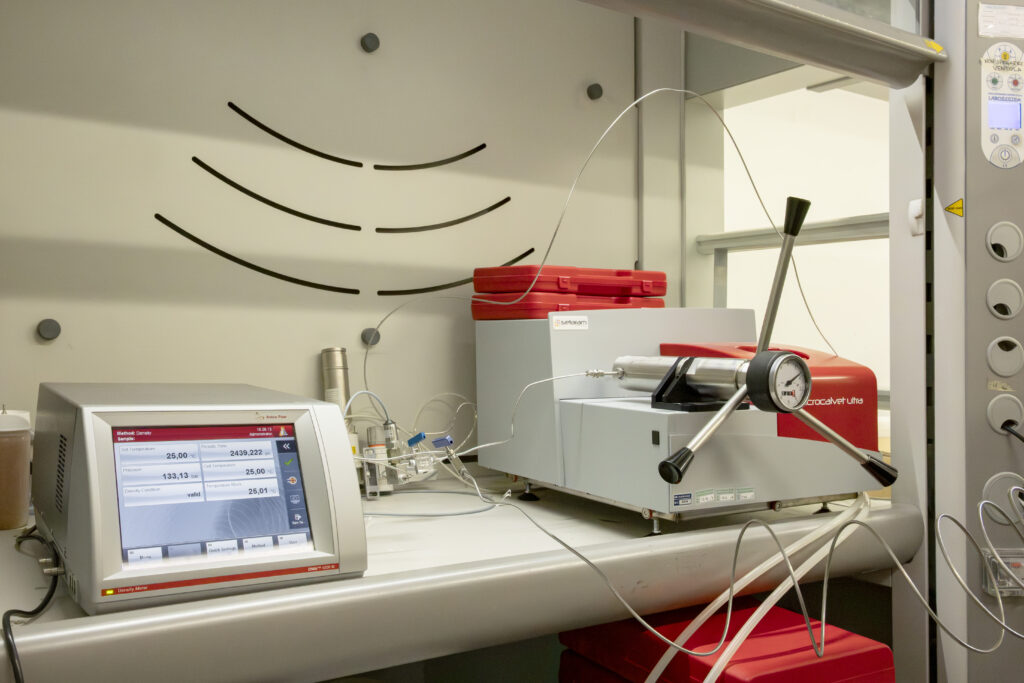

The first is the calorimeter, which allows us to measure calorimetric properties such as heat capacity, fusion enthalpy and specific heat. The device itself is quite standard, but our application is innovative. We use it on fluid mixtures for which there are no reliable experimental data as yet. The actual challenge is not so much measuring the specific heat, but to precisely determine the composition of the mixture inserted, which requires very precise control of the quantities of fluid injected.

The second device is the densimeter, which measures the density or specific volume of the fluid. Once again, the novelty lies in the application. We work on complex mixtures, and the measurement is based on the oscillation of a pipe. But, once again, it is essential to know the exact composition of the fluid in advance to obtain meaningful data.

The third device is the VLE (liquid-vapour balance) system, which allows us to analyse compositions and phases as pressure and temperature vary. It is a sophisticated tool, which complements and integrates the data obtained from the other two, thus offering us a complete view of the behaviour of mixtures.

Finally, we are working on the creation of a viscometer, which was not purchased from the catalogue, but designed and built in-house. The viscometer is the fourth pillar of our equipment. We are completing it these days. It is an essential tool for measuring fluid viscosity, which directly affects heat transfer capacity. We built it in-house, purchasing the sensors and designing the system because those available on the market were either too expensive or did not meet our needs.

Do these mixtures already exist on the market or do you create them in the lab?

Dario Alfani:

We create them, starting from fluids that are normally used individually. For instance, carbon dioxide is widely present in the industrial scene. The system’s behaviour heavily depends on the mixture. Some mixtures present an exemplary behaviour in which the properties correspond to the weighted average of the individual components, while others show significant deviations from the ideal situation.

Our goal is to identify and quantify these deviations as they directly impact on component design and plant performance. For example, specific heat affects the work of a turbomachine or the performance of a heat exchanger. Density, instead, determines the sizing of pipes, exchangers and machines. Accurate experimental data means better designing, and ensuring optimal performance of energy systems.

Tommaso Toppi: I would add that mixtures are composed of at least two components, and the possible combinations are many, even with just two elements. Suffice to consider a mixture containing 1% of one fluid and 99% of the other, or the reverse, and the entire intermediate range. The behaviour of the mixture changes according to the proportion. This makes it impossible to have experimental data for all configurations. Hence the importance of being able to make direct measurements in order to offer specifically tailored solutions.

Antonio Giuffrida: Another advantage concerns optimising dimensions. The choice of fluid can achieve the same performance with smaller volumes, which results in more compact and versatile systems. Hence, the benefits are not limited to efficiency or emission reductions alone, but concern a broader balance between performance, sustainability and integration into application contexts.

So, does improving the mixture mean improving system performance?

Dario Alfani:

That’s right. Improving the composition of a mixture does not only mean increasing energy efficiency, but also reducing environmental impact. In Tommaso’s field, for instance, regulations are becoming increasingly stringent. Many traditional fluids are being progressively banned for environmental reasons.

Tommaso Toppi:

Yes, exactly. Some refrigerants used in the past have a very high greenhouse effect potential, and although the quantities involved are small, their impact is significant. Hence, they are replaced with less harmful alternatives, but the choice is not obvious, as some of the alternatives are less performing.

Dario Alfani:

One of the most promising solutions is to create ad hoc mixtures, selected according to the specific application. This approach offers an additional degree of freedom in the choice of working fluid, allowing to replicate the performance of fluids that have the highest impact, but with a significantly more sustainable environmental profile.

The refrigerant industry has undergone several transformations in recent decades. What are the main stages of this evolution, and how does your research fit into the shift towards more sustainable solutions?

Tommaso Toppi:

From our point of view, sustainability is at the heart of research activities. We develop and make the most of heat pumps and refrigeration machines, with the aim of enhancing their efficiency and making them more suitable for new application scenarios, where they have not been used so far.

The heat pump is considered a key technology for decarbonising the economy, because it allows to provide heat to buildings, industrial plants or district heating networks, without resorting to fossil fuels. In Italy, for instance, domestic heating and industrial steam production still occur mainly by burning natural gas.

There is a strong drive towards the electrification of consumption, underpinned by the idea that electricity will be increasingly produced from renewable sources. In this scenario, having machines capable of transforming electricity into heat at the desired temperature becomes crucial.

One of the trends we are working on is heat pumps for high temperature industrial applications, an area that is still scarcely explored. The choice of refrigerant, i.e., the working fluid, is crucial in this context. Finding the optimal combination of thermodynamic cycle and fluid mixture means improving efficiency, reducing environmental impact, and expanding application possibilities. It is ground-breaking work, which combines technological innovation and sustainable vision.

Is optimising the mixture and thermodynamic cycle to improve efficiency and sustainability the ultimate challenge?

Tommaso Toppi:

That’s right. This challenge inspires various lines of research. For instance, in many heat pumps, the compressor is lubricated with oil, which must be compatible with the refrigerant. If we change the working fluid, it is not said that the same oil will guarantee the former performance of compatibility, stability, lubrication, etc. Often the refrigerant is absorbed by the oil, but we do not know the exact quantity, unless we conduct specific tests.

In this regard, together with the suppliers of the VLE system, we have developed an experimental procedure that allows us to understand how much refrigerant is incorporated by the oil. It is essential to know how much mixture is actually available for machine operation. These are very technical aspects, but they make the difference between a machine that works and one that doesn’t.

What do you expect to be the concrete benefits for the energy industry? What advantages can your work bring?

Dario Alfani:

MISCELAB’s greatest advantage is that it allows us to integrate numerical modelling with experimental verification. To date, our group has worked hard with simulations and models, which are required by industry, and by both Italian and international research projects. But there was no experimental counter-test on fluid properties, which is critical to validate the results.

Now, thanks to the lab, we can strengthen the credibility of our results and offer new options. For instance, in our field of electricity production, we can exploit renewable sources or recover industrial thermal waste. Such applications are still under-exploited but have great potential to reduce the need for fossil fuels.

However, in Tommaso’s field, the aim is to electrify the production of thermal energy. This can be implemented both in industrial sectors, which today produce heat even at low temperatures by burning fossil fuels, and in the civil sector, where gas boilers are still the most widespread technology. Heat pumps powered by renewable electricity can replace these processes with sustainability benefits.

Do the mixtures you study at MISCELAB present risks, or are they a more sustainable evolution than traditional fluids?

Tommaso Toppi:

As Dario mentioned, we are in the midst of a transition from traditional fluids to more sustainable solutions. In recent decades we have gone through several phases. First the problem of the ozone hole, which led to replacing CFCs with new refrigerants. Then we realised that these new fluids, while not damaging the ozone layer, had a very high greenhouse effect potential, even thousands of times higher than CO₂.

Today, many of these fluids, often fluorinated gases, are under observation and progressively banned, especially in Europe, for their effects on health and the environment. Indeed, we are returning to natural fluids, such as CO₂, ammonia, propane, and other hydrocarbons.

These fluids present manageable critical issues. Hydrocarbons are flammable, ammonia is toxic, but when they are correctly managed, they are not dangerous either for the environment or for people. This is the idea behind our research. We want to replace harmful fluids with more sustainable alternatives, without impairing performance.

Dario Alfani: I would add that being able to mix natural fluids gives us an additional degree of freedom. For the reasons described by Tommaso, the choice of a pure working fluid is often limiting. But by mixing them, we can obtain a wider range of solutions, thus selecting the most suitable composition for each application. This allows us to optimise plant performance, while maintaining a reduced environmental impact.

Do you already have active collaborations with companies? What exciting challenges are you currently facing at the lab?

Tommaso Toppi:

The lab initially focused on taking measurements related to the NRRP that financed the purchase of equipment. However, we have already received expressions of interest from companies that could make use of our measuring skills and capabilities.

Furthermore, we are starting a scientific collaboration with the French research centre that developed the VLE system mentioned by Dario. They are probably the only ones in Europe to build such customised, high quality devices.

The collaboration stemmed from the fact that we purchased the instrument and found an original solution, which had never been used before, to measure the miscibility between refrigerant and oil.

This generated a mutual interest in working together to explore new applications on topics that are natural to us, such as refrigerant and oil mixtures. These aspects are relatively new to them.

How do you imagine the evolution of the lab over the next five years?

Dario Alfani:

I hope that the lab will be used to its full potential, especially in collaboration with the industrial world. I would like MISCELAB activities to be integrated into both European and Italian projects as it is a unique structure that can become a landmark for the characterisation of working fluid mixtures, and for the optimisation of energy systems. Not just for us at the Politecnico but for the entire scientific community that deals with energy.

Antonio Giuffrida:

I fully agree with what Dario said. Making the most of the equipment we have today, and perhaps expanding it in the future would be a highly fulfilling experience. We have purchased the devices necessary to characterise fluid properties that we deemed most urgent for our research. But I do not rule out the possibility of further strengthening the lab in due time, with important partnerships and competitive calls.

Tommaso Toppi: Such a lab offers us the opportunity to carry out even the most basic research – as required for theses and PhD programmes – which is often overlooked because it is harder to fund. MISCELAB can become a space where the purely academic spirit and the applicative one can coexist. This is really important. If in five years’ time we can combine basic and applied research for industry, it would mean that we have managed things well. In this perspective, it is essential to attract the interest of the industry. This would confirm that we are doing something useful for the Italian and European production scene, and it would enable us to finance lab activities. In the future, we would also like to add devices to measure thermal conductivity or surface tension. This would complement the current equipment. We have not purchased such instruments as yet due to budget issues.

A personal question, before closing: what excites you in research? What do you find most rewarding in your work?

Dario Alfani:

We have chosen a field of research that is among the most dynamic and strategic today. To me, the lab is an exciting new experience as I had never done much experimental work before. I’ve always been more attached to numerical modelling, where you can control everything, line by line. Conversely, problems are more complex and less predictable in the lab. However, this is what makes them both challenging and fascinating. The world of energy is extremely multidisciplinary. It combines mechanics, thermodynamics, chemistry, electronics … and I am passionate about this variety. That’s why I approached this field.

Tommaso Toppi:

I personally agree with what Dario said. It’s challenging to address multidisciplinary problems. You never get bored. You keep learning new things.

Moreover, I find it important for our work to have a positive impact. Hence, it is always rewarding to feel that, in our own small way, we are helping to improve society.

Antonio Giuffrida:

I confirm what Dario and Tommaso said. The many challenges that surface when we actually work with devices are exciting and intriguing.

We are accustomed to numerical modelling, where it is easier to spot an error, a bug, or a problem. In the lab, instead, we face new circumstances, which are both unexpected and complex. It is an ongoing challenge and, for this very reason, extremely rewarding.