Before they even move into the fields, agricultural robots take shape in virtual environments. Trajectories are studied, errors are measured, time and energy resources are evaluated during simulations, thus reducing costs and risks prior to the actual test. For Stefano Arrigoni, Researcher in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, simulation is not just a technical tool but a bridge between academic research and practical applications in the scene of autonomous agriculture.

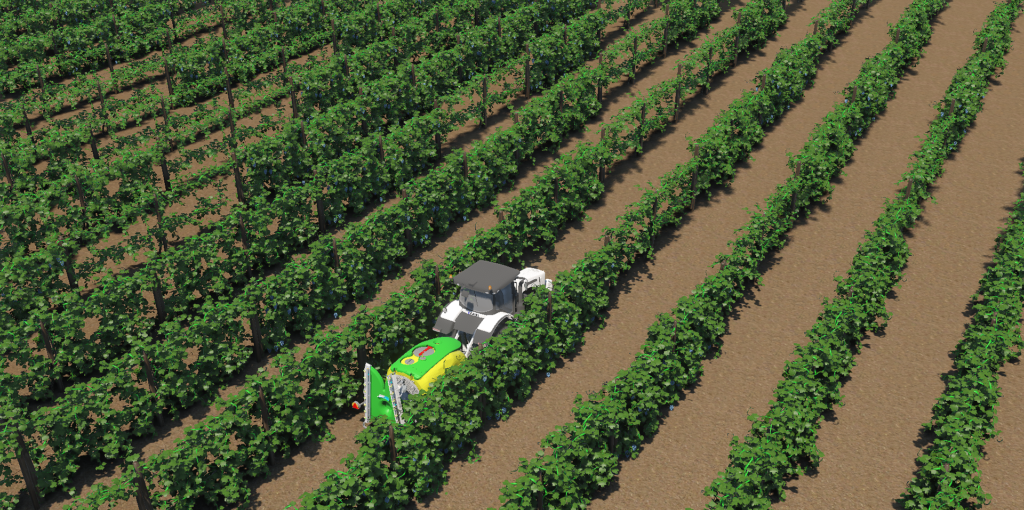

In this interview, Stefano recounts his journey and the results of two studies using 3D virtual environments to design and evaluate autonomous driving systems for agricultural settings, from harvesting in large open fields to precise steering between the rows of grapevines in vineyards.

Let’s start from your own path. How did you get to the Politecnico di Milano and get involved in studies on autonomous driving?

My entire career has unfolded at the Politecnico di Milano, precisely the three-year Laurea (equivalent to a Bachelor of Science), the Master of Science degree, and the PhD. I come from a family with a passion for mechanics – my father is a coachbuilder – so cars have always been part of my life. Even as a child, I was fascinated by the idea of building, touching and understanding how things worked.

During my studies, I increasingly explored mechatronics, control and automation. The Laurea Magistrale (equivalent to Master of Science) thesis marked a milestone, when I spent six months at the University of California, Berkeley. I had the opportunity to personally observe and participate in research activities on autonomous driving. It was already considered a viable option in the US, while in Italy it was still considered part of sci-fi. I returned with the knowledge that those themes would also become central in Europe, just a few years later. Hence the decision to continue along this path even during my PhD studies, and later as a researcher.

Autonomous driving meets agriculture at some point. What inspired this choice?

It stems from a very concrete reflection on the role universities can play in technologically complex areas such as autonomous driving. We have been working on these aspects at the Politecnico for many years, especially in our Department of Mechanical Engineering. Since 2016, we have been taking autonomous vehicles to real-world contexts, such as the Monza racetrack and park. These activities are charged with scientific value. They clearly reveal the possible future of mobility.

However, I realised that the university could hardly be the driving force behind a technological shift such as the automotive revolution on the road. Huge investments and infrastructure are needed. Above all, we need to face safety and regulatory issues that go beyond what a university, by its very nature, can sustain. Ideas often originate in academia. However, they are developed and brought to market by companies.

Hence, at a certain point I asked myself where we could really maximise our impact as a university and as a relatively small research team. Agriculture seemed a natural response. It is a niche area with fewer regulatory constraints. It is more open to practical testing processes.

There was also another key factor. I wanted to apply my knowledge of autonomous driving to a more dynamically challenging context, such as agriculture. Fields are not smooth roads but complex and variable environments. This is precisely what makes research interesting for people like us with a background in mechanics.

Finally, there is also a broader consideration related to European opportunities and priorities. The areas on which research resources are most focused today include mobility, and an agriculture that is increasingly focused on sustainability, on the informed use of resources, and on reducing both herbicides and water consumption. I found that converging these two worlds could be a coherent and promising way of creating a dialogue between research, technology and actual impact.

Simulation plays a central role in your work. Why is it so important?

Conducting tests directly in the field is expensive, time-consuming and hard to repeat in a controlled manner. Simulation allows solutions to be systematically tested, while ensuring cost reduction and high repeatability. It is a tool that allows us to explore many more conditions than those we could actually experience in the real world.

Our studies make use of 3D simulators developed and provided by companies we collaborate with, and which support our research activities. These tools are designed to deal with the complexities of the agricultural environment. They allow us to study specific problems of autonomous farming, introducing realistic scenarios and analysing the impact of slopes, terrain irregularities, and complex operating conditions.

In this regard, simulation becomes the bridge between theoretical models and what really happens in the field. It is not only used to test solutions, but also to understand which ideas are really worth taking out of the lab and testing in practice.

One of your studies concerns harvesting operations. What was the main objective?

We focused on harvesting operations, such as cutting alfalfa or wheat, comparing two field travel strategies that are widely adopted in agricultural practice. The first is the “climb and descent” modewith 180-degree bends in the road, and parallel trajectories. The second is the spiral mode, which starts at the edges and gradually closes towards the centre.

The climb and descent strategy is generally more efficient under ideal conditions. However, we wanted to understand what happens when you introduce the actual complexity of the terrain, such as slopes, irregularities, and lateral deviations. Simulations allowed us to measure working time, energy consumption, and efficiency losses even before field tests. This approach reduces the number of tests required in the field, thus reaching the actual test with already informed and more robust choices.

What have you observed by introducing the actual complexity of the terrain?

We have noticed that the climb and descent strategy is mostly penalised by uneven terrain. In order to avoid leaving portions of the field unharvested, the overlap between trajectories must be increased, with a subsequent rise in the number of passes over areas of the ground.

Simulation allows to quantify this loss of efficiency and, depending on the geometry and field conditions, to assess the most suitable strategy. Hence, it is not a matter of choosing an abstract solution, but of supporting concrete operational decisions.

The second study, instead, focuses on vineyards, which is an entirely different context from harvesting. What is the main challenge of autonomous driving in the vineyard?

The keyword in vineyards is precision. One works on high value crops, where even small lateral errors can cause significant damage to the rows. Unlike harvesting, here it is not so much a matter of covering large areas in the shortest possible time, but of moving with extreme accuracy in narrow and often irregular spaces.

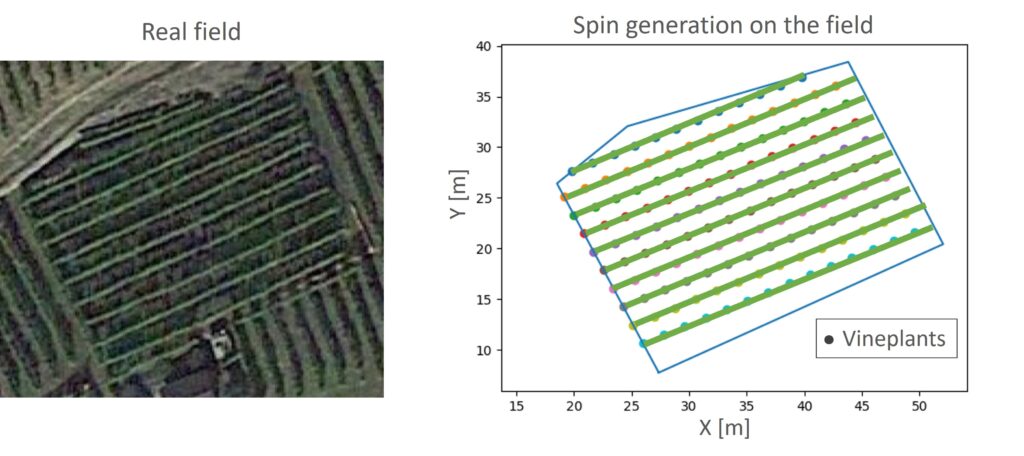

GPS, a widely used technology in agriculture, does not always suffice in this context. When the robot moves within the rows, the lateral error must be minimal, and the satellite signal may not guarantee the necessary reliability. This is why we studied an approach mainly based on on-board sensors, such as lidar and distance sensors. They allow the robot to orient itself relatively to the rows, and to stay in the centre of the path.

GPS is, instead, only used at specific times, such as turning manoeuvres between rows, where conditions are more favourable. Here again, the simulation was essential. It allowed us to test the behaviour of the system in the presence of slopes, undulating terrain, and not perfectly regular rows typical of actual vineyards, which are often located in hilly or terraced areas.

The objective is to understand the range within which these solutions work reliably by both estimating the maximum acceptable lateral error, and identifying the conditions under which automation can really support high quality work.

But how do you really simulate agricultural land, which is generally irregular and changes over time?

This is one of the most interesting challenges because simulators originate from the automotive industry, where the road is an essentially invariable element. In agriculture, instead, the terrain has different slopes, undulations, granularity and, above all, it changes as you work on it.

In our case, we started by modelling the terrain in three dimensions by combining several elements, namely an average slope, wider undulations, and more local irregularities obtained through geometric functions. By varying the parameters of these models, we were able to simulate various critical conditions, and to observe the response of the control systems.

One very interesting aspect concerns the reconstruction of actual fields. For instance, in the case of vineyards, we were able to automatically reconstruct the geometry of the rows by using satellite images, thus accurately reproducing the layout. The height of the terrain can, instead, be estimated or measured with data collected in the field, or – in the future – by means of drones or lidar sensors, leading to the creation of true digital twins of the agricultural field.

This approach allows simulation to be used not only as a testing tool, but as ongoing support. One can simulate a situation, define a working strategy, and then verify it in the actual field, thus reducing errors and inefficiencies.

However, fields do not only have machines. Animals and people pose a serious safety issue. How is this addressed?

This is a crucial, often underestimated issue. Visibility is limited in agricultural settings. High grass, dust raised by work, and the size of the vehicles make it difficult to spot obstacles on the ground. I do not only refer to animals, but also to people who may be in the field, perhaps hunched over or barely visible.

This is why detection is one of the emerging priorities for safety in autonomous agricultural solutions. The idea is to transfer concepts already known in the automotive industry, such as automatic emergency braking, adapting them to much more complex conditions. Fields do not feature clean surfaces and sharp contours. The sensors have to distinguish between vegetation, terrain and real presences, often in highly disturbed environments.

Simulation also plays a key role here, as it allows sensors and algorithms to be tested in difficult scenarios without taking real risks. It is a fundamental step to develop reliable systems capable of increasing not only the efficiency of work, but above all the safety of those who work – or simply find themselves – in agricultural environments.

Looking to the future, what are the main development paths for automation in agriculture?

Automation in agriculture is set to grow a lot considering the extensive scope for efficiency improvements. A driving force in this direction is not only technological innovation, but also a very real problem, namely the increasing scarcity of operators willing to work in the fields. It is physically demanding work that is often unattractive to young people. Automation can help both compensate for the lack of personnel, and make these activities less tiring.

From a technological point of view, autonomous agriculture is a particularly suitable field for the transfer of solutions already developed in other sectors, such as automotive or military. There are already many technologies that can be adapted, although it is not a trivial process. Tools such as artificial intelligence and digital twins can make a real difference in this context.

Another interesting direction is the development of ecosystems of cooperating robots, precisely autonomous tractors flanked by drones or other ground robots, capable of supporting inspections, monitoring activities, and operational decisions. This approach could achieve concrete results already in the short term.

What continues to motivate you in your work as a researcher?

The possibility of seeing something come to life. Starting with an idea, developing it during simulations, and then observing a real system in operation as a result of what you have designed is extremely stimulating. It is proof that research does not remain confined to paper but can be translated into concrete applications.

What advice would you give students who want to approach these areas of research today?

My first advice is to start with a passion for what you want to achieve. The field of robotics and automation are the ideal choice if you want to build, experiment and see something work. It allows you to combine theoretical study and practical activities, really getting your hands on machines and systems. This experience is now much more accessible at university thanks to the laboratories and reforms developed in recent years.

The second piece of advice concerns foresight. The labour market and technologies evolve rapidly. What seems important today may be outdated in five or ten years’ time, while emerging sectors such as artificial intelligence, digital twins, and agricultural robotics will become central. It is, therefore, important to move towards paths that make sense not only in the near future, but also in the distant future, assessing what will have a real impact.

Finally, the most important advice is to do something you really like. The aim should not only be to find a job. Indeed, working on what you love makes research and learning much more rewarding.