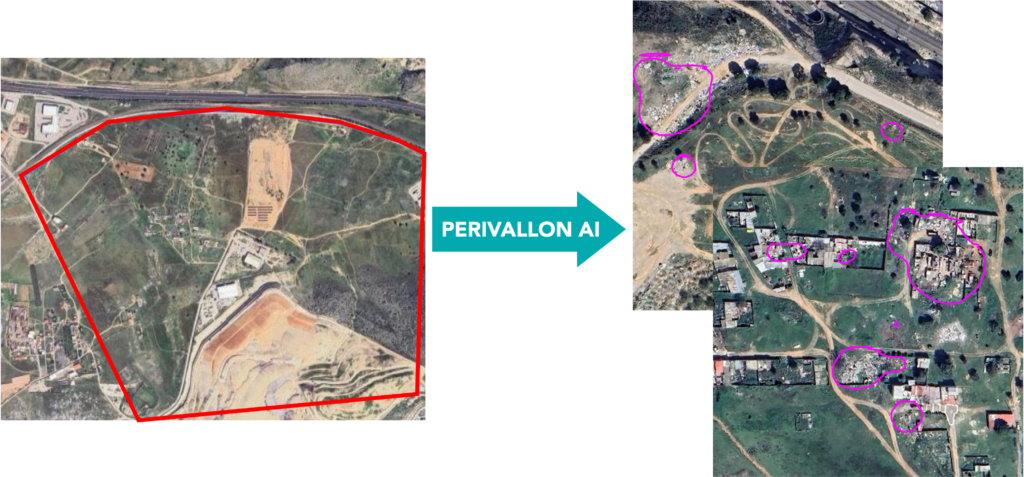

It all stems from a technology that is changing the way Europe deals with environmental crimes; AI applied to images from satellites and drones can detect illegal landfills with more than 90% accuracy. This is the central purpose of PERIVALLON, a project funded by Horizon Europe that brings together 24 partners from 12 countries, including police forces, environmental agencies, universities and research centres: all committed to combating illegal waste disposal, one of the most profitable and pervasive criminal activities within the European Union.

The project comes at a crucial moment, with the recent ruling of the European Court of Human Rights on the “Terra dei Fuochi” area of Campania, which condemned Italy for not protecting the population from toxic fires. The ruling served to indicate the pressing need for innovative tools that can rapidly identify and prevent such activities, which damage the environment and human health.

In Italy, the Politecnico di Milano is playing a central role in developing AI algorithms that can analyse very high resolution images and identify instances of illegal waste disposal in urban, agricultural and industrial settings. The research work is led by professors Piero Fraternali and Giacomo Boracchi, who have spent many years researching and developing AI tools for analysing aerial and satellite images. The young researchers we interviewed were trained in their lab, and have been helping develop the algorithms used in the PERIVALLON project.

The project has led to the creation of AerialWaste, the world’s first public dataset for the detection of waste dumps from satellite images, downloaded by thousands of researchers and used as a base for training neural networks in various countries.

The work has involved collaboration with ARPA Lombardy (the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection), with the Carabinieri Command for Environmental Protection and with several European law enforcement agencies. Development of these technologies has led to drastic reductions in the time they spend on investigations and on monitoring large areas of territory, improving their ability to prevent damage to ecosystems and to public health.

Four young researchers from the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering at the Politecnico have been right at the centre of this research: Federico Gibellini, Luca Morandini, Simona Malegori and Enrico Targhini. We met up with them to ask how they came to be involved in this research, what they have learned in this field, and how they see the future of these technologies.

What sparked your interest in technology?

Federico: “I wasn’t really into IT at first. I used a computer every day, but it wasn’t an area I’d considered studying. It was while I was at high school that I started to wonder how it really worked, and then I discovered computer vision: everything changed from there on.”

Simona: “It all started in my family. My dad was always fixing computers, and I watched him doing it. IT just became a natural language, without me being aware of it. I had fun at high school doing small hardware and software projects, and I realised that was my direction of study.”

Enrico: “I didn’t have a precise route in mind. I liked technology, but I didn’t know what direction to take. The Open Day at the Politecnico was a real turning point; I saw how they worked in the labs and it made me realise that was the right place for me.”

Luca: “I went to a Technical Institute and I wasn’t even sure that I wanted to continue studying. I did the test to try it out, and once I was in I discovered a world that was much richer than I’d ever imagined. IT gradually became my passion.”

When did you discover that research was your way forward?

Federico: “It was during my Master’s thesis that I realised how much I love working on open problems, those that don’t already have a set solution. I realised that I needed more time to delve into computer vision and that research was the ideal context for doing that, without the pressure to produce something straight away.”

Enrico: “I had an offer from a company, but I chose to stay at the Politecnico because the prospect of working on subjects that weren’t yet standardised seemed much more stimulating to me. Research constantly forces you to reframe questions and confront new problems.”

Luca: “After graduation I spent a year as a research associate, and that experience showed me clearly that there were still many technical aspects I had yet to explore. The doctorate was an obvious choice, to give me more time for experimenting.”

How did you come to be working on PERIVALLON?

Federico: “My thesis was already touching on the issues addressed by PERIVALLON and the project was just beginning at that time. So the transition was quite natural; I could play an immediate role in developing the models for satellite image analysis, and in assessing their performance.”

Simona: “I was already working on the software that would contribute to some of the features that were developed in the PERIVALLON project. Taking part in the project meant combining what I was doing with the specific needs of end users, giving my work a very clear application.”

Enrico: “I arrived during the final part of the project, to play a transversal role. This allowed me to work on many different aspects and to understand how the various parts were combined in a single system.”

Luca: “PERIVALLON is one of the main fields of my doctorate. It is not the only line I’m working on, but it’s certainly the one that’s let me see the practical impact of our solutions in the most direct way.”

What was it like collaborating with ARPA, the Carabinieri and the European police?

Enrico: “I was struck by how much larger the problem of waste dumping is than I’d previously thought. Working with ARPA and with the other bodies involved, I realised how widespread this issue is and how difficult it is to monitor the area in a methodical way.”

Simona: “During the plenary sessions with the end users, I definitely saw the need for practical tools to support their work with controlling this problem. Their requests were very specific and related to solving real operational issues.”

Federico: “Talking to ARPA and to European law enforcement agencies leads you to review your priorities and to communicate more effectively. You need to understand which technical aspects are really useful in the field and which are less relevant for operational purposes.”

Luca: “Working with parties so different from each other is a very formative experience. It forces you to always consider the real operational conditions, and to design solutions that are not only correct in theory, but are also usable in complex settings.”

Was there a time when you felt the impact of your work in a tangible way?

Federico: “The working demonstration in Soave was the real highlight. We were able to see for the first time how our models worked in a real context, with operators in the field and uncontrolled scenarios. It was an important step because it demonstrated the practical application of the solutions we’d developed.”

Simona: “For me, the clearest sign came when ARPA requested a further analysis of their data. That was prompt feedback, and it means that what we’ve developed responds to a real operational need.”

Luca: “I remember a plenary session when the end users asked some very detailed questions. This made me realise that our work was entering into their decision-making processes and was no longer just an academic exercise.”

What did you learn by working together on such a complex project?

Enrico: “I learned that research does not follow a straight line. There are very productive phases and others where you seem to be making no progress. You need to accept this pattern in order to continue without becoming discouraged.”

Simona: “It’s vital to have good communication within the team and with the end users. The various activities are closely interrelated and so you need to explain very clearly what you’re developing and the constraints or possibilities that exist.”

Federico: “I realise how important it is to have a common goal. When the team has a shared vision of the end result, the work progresses in a more coordinated and effective way.”

Where do you see yourselves in a few years’ time?

Federico: “I can imagine myself working in a company, in a technical role related to computer vision. This is the area that interests me most, and in which I feel I can specialise further. The experience with PERIVALLON has proved to me that I want to work on solutions that have a real impact on the analysis of visual data.”

Simona: “I see myself in software development, ideally in a context where there is a very direct relationship between what you create and its application by end users. PERIVALLON gave me immediate feedback about the useful nature of the features that we implemented, and this is an aspect I would like to pursue.”

Luca: “I’m thinking about launching a startup, but not straight away. My priority is to complete my PhD, and build on the skills I’m developing. Working at PERIVALLON has taught me how important it is to transform theoretical models into really practical tools.”

What advice would you give to those who want to follow a route similar to yours?

Luca: “Research requires lots of time, and is not a straight path. It’s vital not to get discouraged during the less productive phases and to accept that progress can be intermittent.”

Enrico: “It’s important not to compare yourself too much with other people. Every pathway has its own pace, and its own difficulties.”

Simona: “It’s vital to pursue what you’re really passionate about. Self-motivation is what helps you face all the complexity of study and research.”